|

FORT McHENRY National Monument and Historic Shrine |

|

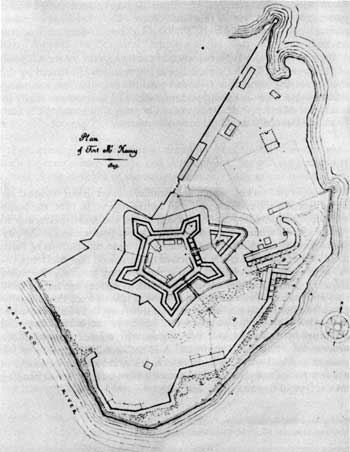

Plan of Fort McHenry made in 1819, showing the fort substantially

as it must have been in 1814.

"The Star-Spangled Banner" After 1815

Though the popularity of "The Star-Spangled Banner" was immediate in Baltimore and the surrounding country, its acceptance by the American people as their national anthem was slow. In 1814, the song was printed in The National Songster, The American Muse, and the November issue of the Analectic Magazine. Such early publications of "The Star-Spangled Banner" omit the author's name and describe the piece as "a new song by a gentleman of Maryland." Between 1815 and 1861, various arrangements of this song were released, bearing imprints of our leading cities; but it was not until 1850 that it appeared in most songbooks for school and private use. By 1861, "The Star-Spangled Banner" had taken first rank among our national songs.

From the first, its most loyal partisans were the Army and the Navy. The wars in which we participated during the nineteenth century did as much as anything to increase the popularity of the song. During the War Between the States, "The Star-Spangled Banner" was claimed by both the North and the South. At Fort Sumter, where the opening shot of the war was fired, this song was played when the American flag was lowered in token of surrender by the Federal forces. In indignation over this episode, Oliver Wendell Holmes added a fifth stanza to the song which appeared in northern editions of songbooks of the period. It was again played at the raising of the American flag following the reoccupation of Fort Sumter with the conclusion of this war. On other occasions it was also played by bands of the armed services—at Manila Bay following Dewey's naval victory over the Spanish, and at Hawaii when it was annexed as a territory of the United States. Toward the end of the nineteenth century, "The Star-Spangled Banner" was heartily accepted by the American people. For this reason, in 1889, the Navy Department ordered the adoption of the song for band music at morning colors. The Army instituted a similar practice. In 1904, Secretary of War Moody ordered the substitution of "The Star-Spangled Banner" for "Hail Columbia," which heretofore had been played with the lowering of the flag in the evening.

During the period between 1904 and 1918, "The Star-Spangled Banner" was widely played in and outside the services. The entrance of America into the First World War was all that was needed for this song to become so universally accepted that a drive could be commenced in Congress to make it our official national anthem. Though a resolution to do this was introduced in the House of Representatives in 1913, the first concerted effort was made in 1918 by Congressman Linthicum, of Maryland, when he introduced a bill to bring this about. In this endeavor, he had the support of many patriotic organizations.

The battle to win approval for the bill was not, however, destined to be easy. Congressmen were badgered with petitions suggesting that such songs as "Yankee Doodle," " Hail Columbia," and particularly "America the Beautiful" which was the other chief contender for the honor, were better suited to be our national anthem. The reasons for opposition to Linthicum's bill were numerous and even today some Americans still express similar sentiments. With much justification, many felt the music of "The Star-Spangled Banner" was too difficult for the average voice to master; moreover, the tune was borrowed. If one were able to sing the melody, the peculiar meter made it difficult to memorize the words.

Furthermore, the opposition to the adoption of the bill was reinforced both by temperance groups and Anglophiles. Some Americans were aghast at the thought of the adoption of this song as our national an them because of the earlier use of the melody with drinking songs. Others felt that the sentiments expressed by the song were foreign to genuine Americanism. They also feared that the cordial relations existing between Britain and the United States might be seriously jeopardized by such lines as "Their blood has wash'd out their foul footsteps pollution," from the third stanza. Such partisans in this struggle felt that for these reasons it would be poor national policy, bad taste, and harmful to the morals and outlook of young school children were this song to win official sanction from the Congress of the United States.

The strength of these lobby groups is revealed by the fact that Congressman Linthicum introduced five similar bills prior to passage of the sixth to make "The Star-Spangled Banner" our official national anthem. Additional evidence of opposition to the adoption of this bill was the national anthem song-writing contest of 1928, sponsored in New York City. Just as there was precedent enough for holding such a contest, the first one known having been held in 1806 by the Militia Military Association of Philadelphia, the dismal failure of such earlier efforts portended a similar fate for this final contest. Forty-five hundred manuscripts were submitted for the $3,000 prize, but no decision was ever reached.

Between 1918 and 1931, evidence of public support for the adoption of Congressman Linthicum's bill was impressively illustrated by the ever-increasing number of civic and patriotic organizations endorsing this measure. The unstinting perseverance of Linthicum was finally rewarded on March 3, 1931, by an act of Congress which made "The Star-Spangled Banner" our official national anthem.

|

|

Last Modified: Mon, Dec 2 2002 10:00:00 am PDT |