|

FORT McHENRY National Monument and Historic Shrine |

|

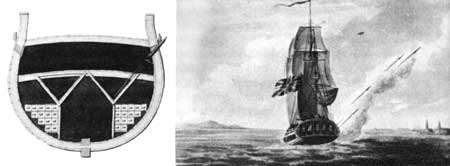

Rocket ship.

Courtesy of the Trustees of the National Maritime.

British Rockets

The rockets used against the fort in 1814 were designed by William Congreve, who, intrigued by the military potentialities of self-propelled missiles, began his experiments in 1804 with the largest skyrockets then available in London. By substituting iron for paper in the construction of the body, reducing the length of the balancing shaft, and improving the black powder propelling charge, Congreve was able to introduce a military rocket with an extreme range of 3,000 yards. After an initial failure, the British successfully employed incendiary rockets against Boulogne in 1806, and thereafter the weapon was employed by both the Army and Navy with satisfactory results. In 1812, the War Office established an independent rocket unit.

British land and naval forces employed the rocket frequently during the Chesapeake campaign. At Bladensburg, they stampeded the inexperienced American militia; but at North Point they were ineffectual, and at Fort McHenry they failed as a military weapon. It is ironic to note that after a long string of successes the rocket is commemorated in a poem which was inspired by an occasion on which they failed miserably.

Rocket launchers on small boats.

Courtesy of the Trustees of

the Museum, Greenwich, England. National Maritime Museum, Greenwich,

England.

The 32-pound rocket, which was customarily used by the British Navy, consisted of a cylindrical body 42 inches long and 4 inches in diameter. Attached securely to the body was a 15-foot-long stabilizing shaft which had been carefully inspected for signs of warping. Congreve designed three types of interchangeable warheads for the rocket— incendiary, case shot, and explosive.

"Since the rocket can project itself without reaction upon the point whence it departs," Congreve was able to design very light and mobile devices to launch the missile. If necessary, the rocket could be placed on the ground and launched in the direction of the target. For an elevated trajectory, the rocket was placed on a slope or its shaft was inserted in a hole. The smaller missiles were usually launched from a hollow copper tube supported by a tripod, from a troughlike chamber set on the ground, or from a simple launcher mounted on the cart in which the rockets were carried. Congreve also designed a ladderlike frame to fire the larger rockets.

In the Navy, this frame, when used on small boats, was divested of its legs and supported by a mast which was raised and lowered by halyards. The rockets, when launched from the ladder-type frame, were activated by a flintlock mechanism, which was attached to the frame, and operated by a long lanyard.

The Erebus, one of the ships which participated in the attack on Fort McHenry, was equipped with a 32-pound rocket battery which had been installed below the main deck. She was formerly a 20-gun sloop-rigged vessel whose hull had been pierced to permit the passage of rockets. Small portholes or "scuttles" were provided similar to those used for the ship's guns.

Congreve was supremely confident that the rocket would supplant the cumbersome gun as the standard artillery piece. He based his optimism on several attractive characteristics of self-propelled weapons. They were simple and economical to manufacture; light and mobile; able to be used in any terrain; and, best of all, the rocket dispensed with the heavy, expensive, awkward gun.

However, Congreve did not realize his dream during his lifetime. The notorious inaccuracy of the missile in flight destroyed its value as an artillery piece. Congreve continually experimented in an effort to remove this defect, which was inherent in the type of rocket he had designed. When he failed to develop an accurate self-propelled missile, military men relegated the rocket to the position of a secondary weapon. They used it only for its demoralizing effect on inexperienced troops, who were often panicked by its eerie appearance and appalling noise in flight.

After 1815, the radical improvement of weapons, powder, and projectiles caused the gradual abandonment of the rocket as a military weapon until World War II, when powerful self-propelled missiles in many forms were designed and used very effectively.

|

|

Last Modified: Mon, Dec 2 2002 10:00:00 am PDT |