|

OLYMPIC National Park |

|

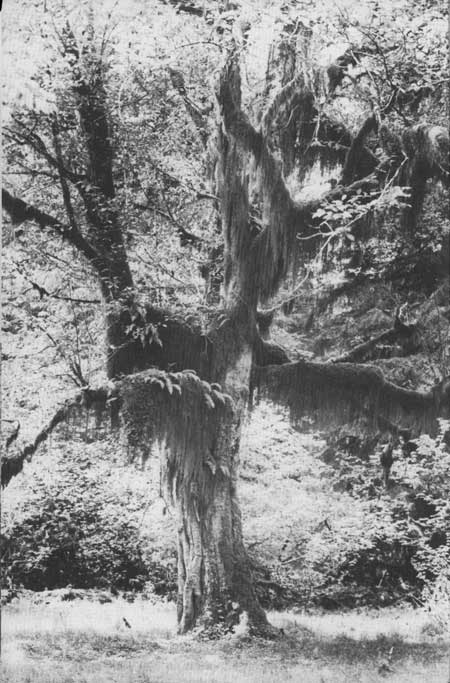

HERE IS TRULY A LIVING WILDERNESS nurtured by the ocean! The Olympic Mountains stand first in line against the moisture-filled Pacific winds. These winds, rising and cooling on the western slopes, drop 12 to 18 feet of rain and snow on forest and mountains each year. Two extraordinary conditions result—a temperate-climate rain forest and an abundance of permanent ice bodies at comparatively low altitudes. Many rushing streams return the water from snowfields, glaciers, and forest slopes to the sea. A complete and endless circuit of water from ocean to land and back to the ocean may be observed from a single mountain vantage point. One can hardly fail to notice a water cycle of this magnitude and completeness or to appreciate its great influence on the Olympic scene.

Olympic rocks tell of their having been formed of mud, sand, and lava, uplifted from the sea; they tell of earth disturbance that alternately submerged the land beneath the sea and elevated it into mountains. The rocks and the shape of the land also tell of colder climates, when ice from the north made almost a glacier island of the Olympic Mountains, and of mountain valley glaciers which sculptured the mountains during thousands of years. The rugged beauty of the Olympic high country, enhanced by scores of mountain lakes, bears testimony to the former presence of these extensive glaciers.

Only about 11,000 years have passed since the last wave of northern ice retreated and laid bare Olympic rocks. Since then the moist and gentle climate has favored the growth of plants and the development of soil. The present Olympic forests and flowering meadows are products of a succession of plantlife from the first lichens and mosses that grew on Olympic rocks. Animals returned when the ice retreated. Plant eaters and meat eaters, large and small, throve in abundance. When primitive man came, he found the land and sea kindly. He easily obtained what he needed for food, clothing, and shelter without depleting the supply.

While most of the Northwest was being explored and settled by the white man during the 19th century, the bulk of the Olympic Peninsula remained virtually unknown. Its rugged mountains, dense forests, and isolation contributed to the delayed advance of modern civilization to this northwesternmost corner of conterminous United States. The Olympic Peninsula thus remained one of the last frontiers, and the park retains genuine wilderness quality, even to its boundaries which descend to sea level.

In this piece of original America the perceptive eye and mind will find a functioning model of nature—a model of earth forces, climate, and life.

The Mountains Are Formed

The present Olympic Mountains were born between 12 and 20 million years ago when western Washington was pushed up into a great range that extended from Cape Flattery southeastward to the eastern part of the State. At the same time, the land to the north and south was depressed and remains depressed today as Juan de Fuca Strait and Chehalis Valley, respectively. The Olympics were further elevated about 5 million years ago. This coincided with the building of the Cascade Mountains and the down-folding of the land between to form the Puget Sound trough. The Olympics were now isolated, having lowland on all sides.

Olympic rocks formed in shallow seas that at least five times have covered western Washington. Sediments washed from adjacent land areas and accumulated on the sea bottom. Muds became shales and sands were cemented into sandstones. Molten lava erupted through these beds and was quickly cooled by the water. Thousands of feet of rock material formed in this way.

When earth forces lifted the sea floor, the sea disappeared, and for long periods there were mountains where the sea had been.

Pressure and heat changed the rocks, especially the sedimentary rocks, which became harder and tougher. Shale changed progressively into slate and phyllite. All of these rocks are found in the Olympic Mountains. The sedimentary rocks and lava flows, originally horizontal on the sea floor, were tilted and folded when uplifted and this is how we see them today.

Long periods of erosion have removed thousands of feet of rock and remolded the Olympics into magnificently rugged mountains. Thus, earth forces build mountains and water slowly carries them back to the sea. So it has been since the first rains fell upon the cooling earth.

Today only the oldest rocks remain, for these were the bottom layers. The greater part of the Olympic Mountains are made up of these rocks, now mostly slates and hardened sandstones. This includes all the rock inside a horseshoe-shaped line running from the village of Sappho east to Lake Crescent, Lake Mills, and Deer Park, then south to the west side of Mount Constance and the north end of Lake Cushman and then west to Lake Quinault. The horseshoe-shaped rim of the mountains outside this line is mostly basaltic lava.

Because fossils are scarce in the oldest rocks, geologists are not certain about their age, but they are thought to be about 120 million years old. The rocks in the outer rim of the Olympic Mountains contain more fossils. These have been found in the sandstones, shales, and limestones interbedded with the thick volcanic rocks. Fish teeth, marine clams, snails, algae, wood fragments, and microscopic shells found here represent forms of life that existed 50 to 60 million years ago.

MOUNT ANGELES SHOWS TILTED ROCKS UPHEAVED FROM THE SEA BOTTOM. |

|

|

|

|

|

Last Modified: Sat, Nov 4 2006 10:00:00 pm PST |