|

OLYMPIC National Park |

|

The Forests and Wildflowers

Our continent has a variety of climates, and each climatic area has its appropriate vegetation. Generally, the interiors of continents do not have forests, but have grass or desert vegetation. The most luxuriant forests develop near oceans where climate is sufficiently moist. This is true of other continents as well as North America.

The differences in the general character of our natural vegetation from coast to coast and border to border are apparent despite three centuries of man's disturbance in the East and one century in the West. Sizeable samples of some of the many kinds of original vegetation are preserved in national parks and monuments. These are precious remnants of our plant heritage that become more valued year by year in proportion to their scarcity elsewhere.

The mild, humid climate of the northern half of the Pacific slope is unusually favorable for forest growth. The most luxuriant of the western forests developed here in unbroken stretches. The forests that girdle the Olympic Peninsula represent the best development of this evergreen forest domain. Its ultimate composition is of western hemlock and western redcedar in dense stands, with trunks commonly 4 to 6 feet in diameter and 125 to 200 feet tall. Their crowns shut out most of the sunlight, but enough gets through to the bottom of the forest for the growth of mosses and ferns. Shrubs grow dense and tall, in places becoming almost impenetrable to hikers. Fallen trees of all sizes soon are enveloped by the lush growth in the damp shade, and in time return to the soil through decay.

Hemlock and redcedar seedlings take root in the forest litter or on prostrate, moss-covered trunks. They are able to live in the deep shade. The most hardy of them outstrip their rivals, and when a vacancy occurs in the forest canopy their growth speeds up. Thus a forest of hemlock and redcedar is maintained. This is the climax forest in the lowlands of the northwest coast. It is the kind of forest the climate here will produce and maintain in the absence of interference.

Interference has been the rule, however, both before and since the coming of man. Therefore, the climax forest is less common than the subclimax in which Douglas-fir is the dominant tree. Forest fires have repeatedly exposed the forest floor to sunlight and thus allowed the development of Douglas-fir, by far the most abundant and widespread tree in northwest forests. In the regeneration of a forest after fire, logging, or other disturbance, it is Douglas-fir that is ever present.

The northwest coast is an evergreen land. This may not be apparent in summer, however, when all plants are green. Not counting the numerous mosses that are always green, there are 73 species of evergreen plants on the Olympic Peninsula.

RAIN FOREST

An extraordinary forest has developed along the western slopes of the Coast Range where moisture is available in the greatest abundance. The most typical and beautiful expression of this coastwise forest is found in the western valleys and on the coastal plain of the Olympic Peninsula. It is the most luxuriant growth in any temperate climate and may properly be called a rain forest. This temperate-climate rain forest, however, is not like the rain forests of the hot, superhumid tropics. Here, there are tall conifers instead of broad-leaved trees; there are mosses and ferns on the ground instead of an understory of vines.

DRAPERIES OF CLUBMOSS HANG FROM LIMBS IN THE RAIN FOREST. |

The rain forest is principally distinguished by the presence of Sitka spruce. This tree grows only in a narrow belt along the coast from northern California to Alaska. The other trees of the rain-forest community have much wider distribution.

The trees of this forest are among the largest in the world. Many of them have trunks that exceed 10 feet in diameter at 4-1/2 feet above the ground, and are up to 300 feet tall. The largest known trees in the park for the most common species are: western redcedar, 21 feet 4 inches in diameter; Sitka spruce, 13 feet 4 inches; Douglas-fir, 14 feet 5 inches; western hemlock, 9 feet; and Pacific silver fir, 6 feet 10 inches.

A visit to the rain forest offers a surprisingly enjoyable experience. Although it is possible to drive through some sections, this provides only a view of the trees. A forest is more than a stand of trees—it includes animal life, smaller plants, and micro-organisms, such as bacteria. All these serve the forest and in turn, their well-being depends upon the forest. They form the forest community.

Splendid examples of rain forest may be seen in the Hoh, Queets, and Quinault Valleys, but the Hoh Valley is the most accessible. A paved road runs 19 miles up the Hoh from U.S. 101, ending 7 miles inside the park boundary where a National Park Service campground has been developed. The Hoh River Trail starts just beyond the nearby visitor center. It extends 18 miles to Glacier Meadow, close to Blue Glacier on Mount Olympus. Approximately 12 miles of it is in rain forest along the valley bottom. Only a small fraction of this distance need be traveled, however, to see the forest.

Unexpectedly, one finds this forest beautifully luminous. It is filled with soft, green light that drops down where it can find room between the towering spruces and hemlocks. In the lower levels of the forest it filters through the translucent leaves of the vine maple and bounces from one green surface to another. Nature, in an exuberant mood, has lavishly decorated this forest with mosses and clubmosses. Moss carpets, with patterns of Oregon oxalis and beadruby, cover the forest floor. The same material upholsters fallen trees and the trunks of those standing. Mosses ascend to the very tops of some of the tallest trees. Arched trunks of vine maple are cushioned with them. Curtains of clubmosses hang from the same archways, separating one green forest room from another.

The forest cycle from seed germination to death of giant trees and their return to soil may be seen here in the course of a short stroll. This is a cycle endlessly repeated. No part of it is disturbed by man. Trees felled either by uprooting or by breaking of the trunk are scattered everywhere in various degrees of decay. Rain-forest trees have shallow but widespreading roots. To obtain nourishment, there is no need for deep roots where water is available in dependable abundance. But shallow roots in saturated soil do not always anchor trees firmly enough against storm winds.

MOSS AND BEADRUBY PATTERN ON THE FLOOR OF THE RAIN FOREST. |

Though dead and prostrate, the fallen trees still have an important function in the forest. They are soon accepted into the forest-floor community and become covered with lichens and mosses. Various fungi and bacteria attack them from within. They become nurseries for spruce and hemlock, whose seedlings prefer rotting wood. The most vigorous seedlings send their roots down the flanks of such old nurse logs, if big enough, will last until the trees they foster grow to large size. Colonnades of huge trees may thus be seen straddling old moldering logs. Seeds may even take root upon a broken stump 12 feet or more above the ground. The roots reach the soil after creeping down the full length of the stump. The result, when the stump rots and crumbles away, is a tree standing on stilts. Thus the forest is regenerated. New life compensates death. There is neither increase nor decrease in total amount. What is dead eventually returns to soil and feeds the living. This is brought about through the work of saprophytes—plants without chlorophyll, the substance which gives plants their green color. They must obtain their food already made and are content to take it dead. Many of these are mushrooms and other fungi with colorful and beautifully shaped fruiting bodies. No better description of their function in the forest can be found than that written by Donald Culross Peattie.

Breaking up the debris of what was living, releasing the precious materials in it, these fungi, and certain bacteria, retrieve the vital elements from what would otherwise be a permanent and cumulative and ultimately disastrous loss. They are part of what we call decay, but they are as much a part of life. They turn over its wheels. . . .

THE SHELF FUNGUS IS ONE OF THE NUMEROUS ATTRACTIVE FUNI. |

MOUNTAIN VEGETATION

A visit to Olympic is not complete without at least one trip into the high country. Aside from the numerous trails that lead up into the mountains, there are two high country areas that may be reached by car. These are Hurricane Ridge and Deer Park. Whether the trip is made on trail or on road, an understanding of the changing pattern of plantlife will make it more enjoyable.

The climate at the top of a mountain is unlike that at the base; accordingly, the plants are different. Plant scientists have found that these vegetation differences on a mountain are similar to the changes seen between the equator and the poles. Generally speaking, each 100-foot rise in elevation is equivalent to about a 20-mile distance north. Although the change may be gradual, there are distinguishable belts of vegetation on a mountain. These belts are called life zones and have names that indicate their correspondence to zones between the equator and the poles.

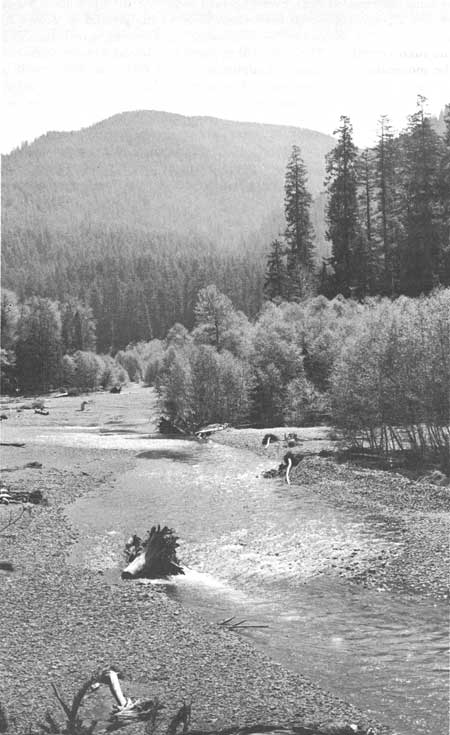

RED ALDER IS THE FIRST TREE TO GROW AT THE EDGE OF THE CHANGING COURSES OF THE RAIN FOREST RIVERS. |

Altogether there are four life zones in the Olympic Mountains: Transition, Canadian, Hudsonian, and Arctic-Alpine. The vegetation of the last three is similar to that of regions to the north at lower elevations, as indicated by their names.

The Transition zone in the Olympics is the lowest. It is intermediate between southern and northern vegetation. The lowland forests, including the rain forest already described, are in this zone.

The next two zones also are forest, but somewhat different. The highest, or fourth, zone is treeless. The boundaries between the forest zones here are not sharp; it is difficult to know exactly where one ends and the next begins. This merging of forest zones in the Olympic Mountains may be due to the equable temperature extending well up the mountain slopes.

The Canadian zone should be apparent when an elevation of 2,000 feet is reached. The forest of this zone is somber compared with that of the Transition zone. Although it has many kinds of small shrubs and herbaceous plants, it lacks the striking greenness of the Transition forest. Western white pine and Pacific silver fir have entered it. Western redcedar is absent, while Douglas-fir and western hemlock remain. There are numerous saprophytes on the forest floor—most of them flowering plants such as pinedrops, Indian-pipe, and coralroot.

The Hudsonian zone is next, and is the highest one having forest vegetation. Around 3,500 feet elevation there is a mingling of Canadian and Hudsonian trees. Some trees of the Canadian zone are still found, but some different kinds are included in the forest composition. The characteristic Hudsonian zone trees are mountain hemlock, Pacific silver fir, alpine fir, and Alaska-cedar. The last-named has typical cedar foliage. Its branches and twigs droop as if they were wilted. Trees in this zone are much smaller than those at lower altitudes and become still smaller with every upward step. At the uppermost fringe of tree growth the winds hold them close to the ground as deformed growths. This is known as krummholz, a German word meaning "crooked wood." The name is applied to stunted forest commonly found in alpine regions. Timberline in the Olympic Mountains is generally at about 5,000 feet, which coincides with the height of many of the ridgetops. The beginning of the Hudsonian zone is the beginning of the high country. The sky is bluer and in summer an alpine fragrance adds zest to the air. The forested slopes give way, in depressions, to meadows that are brilliant with wildflowers in summer. Basins carved by snow and ice hold numerous mountain lakes, with streams flowing into and out of them.

THE CANADIAN AND HUDSONIAN LIFE ZONES ARE REPRESENTED IN THE RESPECTIVELY HIGHER FOREST BELTS THAT LIE ABOVE LUSH RAIN FORESTS. |

The Hudsonian meadows, in depressions above 3,500 feet, are knee-deep in grass in July and August, and flowers form a medley of color. Aster, pedicularis, arnica, shootingstar, cinquefoil, and false hellebore are among the conspicuous flowers there.

Stream margins and marshy ground are preferred by such plants as marshmarigold and globeflower.

Higher in the Hudsonian zone there are prairielike meadows where flowers bloom in profusion. Extending 60 miles across the north and east sides of the park there are thousands of acres of this meadowland on the ridges. Hurricane Ridge is in the midst of this and presents some of the finest flower displays. Some slopes in early summer are white with avalanche lilies, one of the most abundant and widespread of the mountain flowers. Near timberline they grow among the trees, as well as in the open. Other meadows are yellow with pure stands of glacier lily, one of the earliest of spring flowers. Impatient with winter, it pushes through the thinning snowbanks. Where soil is deep, subalpine lupine blooms profusely. Among the most common and conspicuous in rich meadows are larkspur, buttercup, cinquefoil, paintbrush, arnica, tiger lily, and mountain buckwheat.

MEADOWS AND CLUSTERS OF TREES OF THE HUDSONIAN ZONE. |

Several plants found in the mountains in the northeast part of the park, where rainfall is lighter, are more typical of the hot, arid lowlands of eastern Washington and Oregon. Some of these are nodding onion, woolly eriophyllum, and barestem lomatium—their presence in the mountains may be due to the fact that the broad ridgetop meadows in the northeastern part of the park are remnants of a lower plain where these plants grew before the Olympic Mountains had risen to their present height. As the mountains were pushed up, these plants could have continued to grow and reproduce despite changing conditions.

On hillsides where the rock has weathered only into chips, or where little soil has formed, carpets of spreading phlox and rosettes of Lyall lupine are most conspicuous in early summer. Some plants grow on talus slides, on rocks broken and tumbled from peaks above, and on rocks laid bare by retreating glacial ice. Lichens and mosses, pioneers among plants, etch the rock with weak acids and thus start the slow conversion of rock into soil. Some flowering plants are pioneers, too. Common ones growing in crevices and soil pockets among the rocks in the Hudsonian zone are smooth douglasia, alumroot, and bluebell. Eventually, a flowered meadow or forested slope develops where first there was only bare rock.

The Arctic-Alpine zone is the region above timberline. It corresponds to the arctic meadows of northern Canada. In the Olympics its lower limit is about 5,000 feet and its upper limit is the tops of the peaks.

It is a harsh environment. Its shallow soil and rocks, its wind and prolonged snow and cold exclude all but the hardiest perennials. Annuals cannot live there. One growing season is too short for a plant to start from seed, complete its vegetative growth, flower, and ripen its seeds. Many of the plants are surface plants, such as mosses and lichens, which do not produce flowers. But even the flowering plants hug the ground. Their over-wintering buds are at or below the ground surface. It is a struggle for moisture and against time. Only low perennials, having small, tough leaves covered with hairs or wax, are able to survive. These properties help protect the plants against loss of water.

There are 8 kinds of mountain plants in the Olympics that are not known to grow anywhere else. It appears that these plants grew in the Olympic Mountains before the ice came and were able to survive on ridgetops that remained free of glacial ice during the long cold periods. They are thus relicts from preglacier time. None of them are trees and only two are shrubs. All the rest are herbs. Several of these, among which piper bellflower and Flett violet are especially attractive, may be found on Hurricane Ridge and on the upper slopes of Mount Angeles.

Snow is vital to mountain flowers. It provides most of the moisture for their growth and governs the length of the growing season. Spring flowers appear earliest where the snow melts first. Where snow piles up deeply, it may not melt completely till midsummer or may melt too late for plants to complete a season's growth. On northern slopes the snow may remain all summer, and there can be no growing season.

The high country has many floral patterns, which change as the seasons progress. The flower displays are usually best around the middle of July. Flowers of spring, summer, and autumn are blooming then, according to the progress of the seasons in different elevations and habitats.

ALPINE FIR GROWS NEAR TIMBERLINE. |

|

|

|

|

|

Last Modified: Sat, Nov 4 2006 10:00:00 pm PST |