|

OLYMPIC National Park |

|

Wildlife

One of the reasons for establishing Olympic National was to insure "protection and preservation of interesting fauna, notably the rare Roosevelt elk . . ." There are 54 species and subspecies of wild mammals occupying their primitive homes on the Olympic Peninsula (Murray L. Johnson and Sherry Johnson, Check List of Mammals of the Olympic Peninsula). Probably all of these occur within the park. The wildlife picture is not a static one, however, as natural disturbances, time, and man bring changes in numbers, kinds, and distribution.

Climatic changes have greatly affected the animal life. There have been periods of extreme cold and periods of warmth. At least four times the ice-age glaciers advanced and melted back. When ice sheets moved down from the north and extensive glaciers formed in the mountains, the animals left. When the ice retreated, the animals returned. Not all animal types were able to survive, so that some animals that once lived in Washington are now extinct. One of these was the mastodon, resembling the present-day elephant. In 1950, a fossil skeleton of a mastodon was found in an excavation on a farm near Port Angeles, and tusks and parts of skeletons have been found from time to time in the bluffs east of Port Angeles.

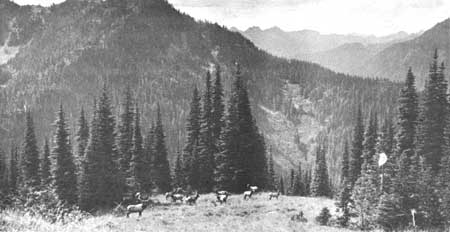

ROOSEVELT ELK. THE BULLS GROW NEW ANTLERS EACH YEAR. |

Because the Olympic Mountains are isolated from other mountains, some animals of the Pacific Northwest have never found their way to the park. For instance, several kinds of animals in the Cascade Mountains are unknown in the Olympics. These include the mantled ground squirrel, pika or cony, and red fox. The wolverine, now rare in the Cascades, has never been seen in the Olympics. But animals move about, and it is entirely possible that there will be natural additions to the Olympic fauna. Dr. Victor B. Scheffer has stated that the red fox and the porcupine are expected to invade the Peninsula sometime in the present century. During 1951, two porcupines were seen on the Peninsula near the ocean—one at Kalaloch and another south of Queets Village.

Other changes have been brought about directly or indirectly by man. The Olympic wolf—a big, gray, magnificent animal—was once fairly numerous, but, because of merciless poisoning and hunting before the park was established, it is now probably extinct.

The coyote, renowned for his ability to survive civilization, has invaded the Olympic Peninsula during the present century. To some extent this animal fills the ecologic niche left vacant by the disappearance of the Olympic wolf.

Long before the National Park was established, mountain goats were brought from British Columbia and Alaska and released on Mount Storm King, near Lake Crescent. The transplanted animals have thrived and multiplied, and have spread eastward across the park.

YOU AND THE ANIMALS

The animals of the park are an integral part of the wilderness scene. The principal purpose for which the park was established was to preserve and display the natural wilderness. Thus, the animals are wild, living in their natural habitat. Not only must the animals and their normal habits be preserved, but their wilderness home as well. Whether the presence of man will be disturbing to the wilderness and its dwellers depends upon how humans behave in it. Any act that would tend to break down wilderness animal behavior is harmful to wildlife and is a violation of park rules.

Proper behavior of park visitors in the presence of national park animals may need explanation. The feeding of wild animals by man is harmful to their best interest. For thousands of years they have been able to feed themselves, and their continued well-being depends on their doing so now and in the future. For example, black bears in Olympic have not yet become troublesome, but bears, by nature, are inclined to become spoiled if artificial feeding habits are encouraged. Bears normally eat many kinds of plant and animal foods, but a camper's larder contains tidbits that would tickle the palate of any bear. If an animal learns to associate food delicacies with campers, he will repeatedly seek experiences of that kind to the everlasting annoyance, misfortune, and even tragedy of the campers. The thoughtless camper who willfully, or negligently, starts the bear on the road to ruin may escape the consequences. It is the bear himself and people who appear on the scene later who suffer for the deeds of earlier campers. The bear may become a dangerous nuisance and may have to be destroyed.

The only intelligent and humane solution is to refrain from all practices which tend to disturb or change the animal's normal way of life. Self-restraint and good camping practice are necessary in order to accomplish this. Under no circumstances offer food to a bear or leave food or garbage where he can get at it. Remember that he, is powerfully muscled and can climb trees. Refuse, including cans and bottles, should be burned not only to destroy all that is edible but to destroy food odors. Then, when the charred cans and bottles are placed in refuse containers or buried, the bears will not smell them and dig them out.

SEEING THE MAMMALS

As long as animals remain completely wild there is little danger from them. The majority of mammal species are small, rare, secretive, or nocturnal, so for these or other reasons they may not easily be seen. They will try to avoid contact with people, and your problem will be to find them and to get close enough to see them well, without disturbing them. To do this, it is necessary to study their habits and to meet them on their own terms.

There is no scarcity of animals in Olympic; but the conditions for seeing even the larger ones, such as elk, deer, and bear, are not as favorable as in Yellowstone National Park, for instance. Olympic has less open country where unobstructed views may be enjoyed, especially in the lowlands. Even in the high country the rolling or rugged topography allows animals to move quickly out of sight behind ridges or rock outcrops.

Do not let these difficulties discourage you. The following suggestions may help you to see some of the more interesting mammals:

The ROOSEVELT ELK is also popularly known as the Olympic elk, because the largest remaining herds of this animal are on the Olympic Peninsula. The number here totals approximately 6,000 animals. These elk, however, still are found in various other parts of their original range, which includes the coastal forests from southern British Columbia to northern California.

The elk is the largest of the American deer family, except the moose. The bulls sometimes weigh as much as 1,000 pounds and the cows, 700. Both sexes have a heavy brown mane and a pale, yellowish rump patch. The bulls carry antlers, which are shed in late winter.

ROOSEVELT ELK IN A LUSH MOUNTAIN MEADOW IN OLYMPIC'S WILDERNESS. |

While emphasis has been placed on the proper relationship with the bear, the same attitude toward other animals will help insure their well-being and your safety. Any attempt to feed a deer or a bear invites injury. Proper conduct in relation to wild animals is so important that regulations now prohibit the feeding, touching, teasing, or molesting of any bear, deer, elk, moose, bison, bighorn, or pronghorn in National Parks. The first three are found in Olympic.

Generally, the elk spend winters in the lowland forests and summers in the higher mountain meadows. Many of them, however, remain in the lowlands even in summer, so that it is possible to see elk in some of the western valleys of the park the year round.

During certain times of the year they are vocal. In May and June when the calves are born the cows sometimes bugle, and more frequently the calves give a high-pitched squeal.

Elk are polygamous and during the rutting season a bull will gather a harem, consisting of a few to a dozen or more cows, which he attempts to hold against all other bulls. There is much bugling by the bulls then—thrilling wilderness calls. You will probably recognize the source of this call the first time you hear it. The bulls become less shy during the rutting season and will permit closer approach. This should be done cautiously, however.

Almost any high-country meadow, except in the north to northeast part of the park, may hold a herd of elk from July through September. Cows, calves, and yearlings gather and remain in large herds until split up by the bulls when the mating season begins in the autumn. During summer, bulls remain apart from the cows, either in small groups or alone. The rutting period lasts from early September to mid-November, tapering off in the last month.

When the snow deepens in the mountains the elk that have summered in the high country come down into the valleys, where they gather in herds that may number 50 or more animals.

COLUMBIAN BLACK-TAILED BUCK. |

The COLUMBIAN BLACK-TAILED DEER is one of the most frequently observed larger mammals. Usually, it is seen in the early morning, late afternoon, evening, and often at night—the preferred feeding times. It remains bedded down in some secluded spot during much of the day. Anyone driving in western Washington at night is likely to see a deer suddenly bound out of the forest onto the highway. Where highways pass through localities having large deer populations, signs warn motorists of this danger.

In summer, deer prefer the upper Hudsonian zone, where forest and meadow mingle to provide both nutritious food and nearby secluded shelter. Hurricane Ridge and Deer Park are favorite summering grounds, and a visit to either area at deer mealtime is likely to be rewarding.

With encouragement and repeated opportunities to sample human food, a deer will become "spoiled"—a beggar lacking the sleekness and alertness of a wild creature. It is then no more than a specimen-like a plucked flower about to wilt. Also, it is potentially dangerous to the person who tries to feed it, for it can, and may, strike damaging blows with its sharp hooves. In the autumn mating season, males, tame or wild, can be dangerous.

DEER FAWNS ARE COMMONLY LEFT ALONE WHILE THE MOTHER FEEDS. |

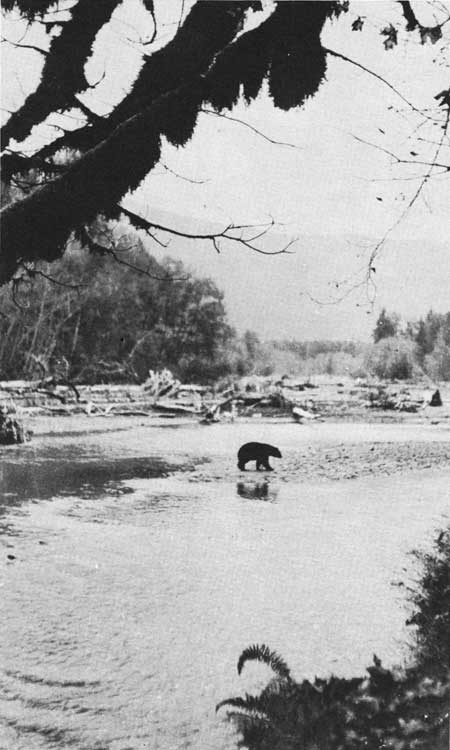

BLACK BEARS may be seen from sea level to alpine meadows in summer and early autumn. The socially disinclined bear travels alone, except for the mother with cubs. However, several bears may be in the same neighborhood for the same reason—food. From a ridgetop, the sleek, black forms may be seen against the green of the lush meadows below, where they search out ants, small rodents, and succulent herbage of various kinds. On mountain slopes covered with ripened huckleberries in late summer, bears become so engrossed with gorging on the delectable fruits that they may be stalked from downwind. A bear's keen nose quickly distinguishes nonwilderness odors. Should a shifting breeze waft a scent message his way, you will have to find your self another bear to stalk. A bear's hearing is good, but his vision is less acute.

Bears frequent valley bottoms and other lowland areas during late autumn, winter, and spring and may be seen along streams during salmon runs. Apparently, bears in the Olympics do hibernate, but the mild winters make a long dormancy unnecessary. It appears that all Olympic bears are black—the brown pelage phase has not been reported.

A black hear is not a dangerous animal unless he has learned to seek food from people or from their camps. Although a mother bear with cubs is not to be trifled with, a bear without those family responsibilities is easily frightened by a shout or other sudden loud noise.

BLACK BEAR. AN UNSPOILED ANIMAL IN ITS NATIVE WILDERNESS. |

OLYMPIC MARMOTS live just above or below timberline usually near well-watered meadows bordered by alpine fir clumps. Some are found on windswept ridgetop meadows or on rockslide areas. Marmots come out of hibernation in May and remain active until early September. They are most active in the early morning or evening during warm summer days. They have many burrows, which are easily spotted on alpine meadows. While they may feed long distances from their home dens, they are seldom far from burrows down which they can scurry at the first sign of danger.

Although marmots can best be seen and photographed on Hurricane Hill or Deer Park, they also occur in other high-country locations. The marmot blends well with his surroundings. You may not be aware of his presence until you hear his shrill alarm whistle, which at first you may mistake for a human whistle. It is so frequently heard in marmot territory that the name "whistler" has been given the animal.

OLYMPIC MARMOT LIVES IN BURROWS AND ROCKPILES NEAR TIMBERLINE. |

|

|

|

|

|

Last Modified: Sat, Nov 4 2006 10:00:00 pm PST |