|

BADLANDS National Park |

|

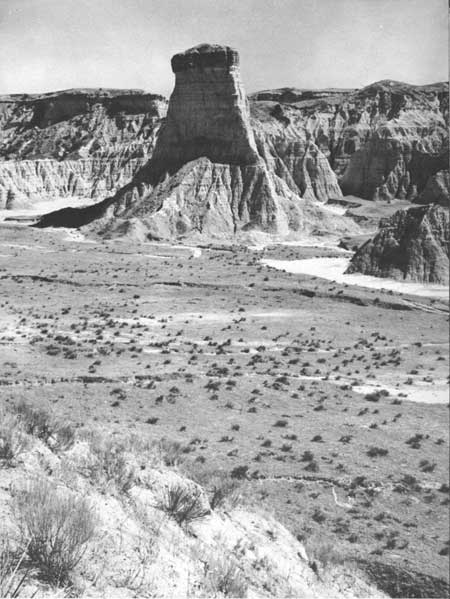

BADLANDS NATIONAL MONUMENT is a wonderland of bizarre, colorful spires and pinnacles, massive buttes, and deep gorges. The forces which carved these features have not only created a unique topography; they have given a strange beauty to an almost desolate land. Here, from many points of vantage you can see with clarity the process of wearing away the land and cutting new and complex features in an older surface of more subdued form. The rapidity of the wearing away, or erosion, of a land poorly protected by vegetation is also well illustrated.

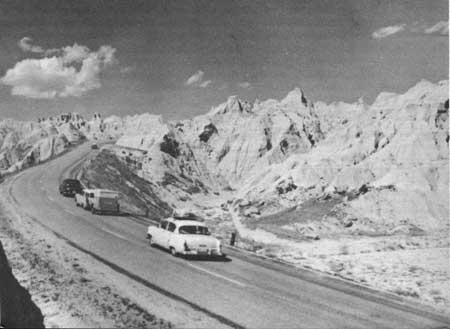

The highway through the badlands is a show window through which you can look into the heart of one of the world's most dramatic demonstrations of the great sedimentary land-building process, shown in storybook form in the color-banded formations. These sedimentary deposits, derived from the breakdown and transportation of older rocks, have been and are being cross-sectioned so rapidly by erosion that the story of earlier deposition is being revealed almost with the speed and continuity of a motion picture. A short walk into the badlands, perhaps on the marked route from "The Door" (near the east entrance to the monument) will make the raw action of badlands erosion a vivid personal experience.

The badlands contain a myriad of erosional forms. SOUTH DAKOTA HIGHWAY COMMISSION PHOTOGRAPH |

You will not have to hike into the badlands, however, to appreciate its complex of sharp ridges, steep-walled gullies and canyons, pyramids, knobs, and spires. You can drive along the highway through the monument and stop at parking overlooks to view this landscape of varied forms and pleasing, soft colors. It seems to be another world. The scene that unfolds may raise the question, "What is going on here?"

The story of what is happening began millions of years ago. This semiarid region was then a broad plain of marshes and of sluggish rivers flowing eastward and depositing on their flood plains layers of silt, sand, and gravel. Lush vegetation covered the land. Animals that no longer exist were abundant. As they died, the remains of some of them were buried in the river sediment or sank into the ooze and decaying vegetation in the marshes. A long chapter in the majestic story of animal evolution is vividly told by the abundant fossil remains.

Gradually, because the land was rising, with the change in elevation affecting the climate, the well-watered land of luxuriant vegetation gave way to the semiarid high-plains region of today. Aimlessly wandering rivers no longer deposited their loads of sediments across a broad region, but rather began to cut into and carry away the layers formerly deposited. This rapid cutting-away action is going on today. As streams cut back into the high plain, the "bad land" is forming. As erosion exposes the layers of rock and the remains of plants and animals, it makes it possible for geologists to help us visualize life and landscapes that were here millions of years ago.

Modern roads lead into the heart of the badlands |

Location of the Badlands

Several areas in the United States have a type of landscape called badlands. Some of those in the National Park System are described on page 46. The classic example, however, is here in the "Big Badlands of South Dakota." Since the White River flows through much of the area, references are found to the "White River Badlands." Geologists have placed this formation in the Oligocene Epoch. (See geological time chart, p. 6, and the description beginning on p. 5.) To remove any doubts as to identity, they have applied the title "White River Oligocene Badlands." All of these names refer to the same locality, mostly in southeastern Pennington County and northeastern Shannon County, in South Dakota. Southwestern Jackson County and northwestern Washabaugh County also have colorful examples of this weird landscape. (See map, pp. 22-23.) Both exceptional and typical portions of these extensive badlands are within the National Monument.

|

|

|

|

|

Last Modified: Sat, Nov 4 2006 10:00:00 pm PST |