|

SAGUARO National Park |

|

Adaptation of Plants to a Desert Environment

You can realize from the foregoing that the monument contains three environments—desert, foothill, and mountain. The Tanque Verdes represents the foothill region, and the Rincon Range, the mountains. All of the area immediately adjacent to the base of these uplifts is the desert wherein much of unique interest may be found.

It would be enlightening to know how many species and varieties of plants which developed during the past 60 million years or so have failed in their attempt to survive under Sonoran Desert conditions. It is even more interesting to study the hundreds that have survived and to try to determine just what structures they have perfected and what methods they have originated in order to establish and maintain themselves in a land so inhospitable toward the usual forms of plant life. All of these plants in the desert area belong within the Lower Sonoran Life Zone, which is discussed in a later chapter. Let's look at some that are easily found in Saguaro National Monument.

NON-SUCCULENT PLANTS

For pure ingenuity in devising a variety of ways and means of making the best of an inhospitable environment, the many species making up the non-succulent type of desert vegetation provide an absorbing field for study. There are two ways to survive the harsh desert climate; one is to avoid the periods of excessive heat and drought; the other is to adopt various protective devices. The short-lived plants follow the first method, the perennials, the second.

The Ephemerals, or Short-lived, Plants

Every spring that follows a winter of normal rainfall, the desert floor is carpeted with a lush blanket of fast growing annual herbs and flowers—the early spring ephemerals. Many of these "quickies" do not have the characteristics of desert plants, in fact, some of them are part of the common vegetation of other climes where moisture is plentiful and summer temperatures much less extreme. What are these "foreign" plants doing in the desert, and how do they survive? With its often frostfree winter climate and its normal December-to-March rains, the desert presents in the early spring ideal growing weather for annuals that are able to compress a generation into several months. Several hundred species of plants have taken advantage of this situation.

There is a WILD CARROT (Daucus pusillus), which is a summer plant in South Carolina and a winter annual in California where it is called "rattlesnake weed." In the desert, its seeds lie dormant in the soil through the long, hot summer and the drying weather of autumn. Then, under the influence of winter rains and the soil-warming effects of early spring sunshine, they burst into rapid growth. With a host of other species, this early spring ephemeral is enabled by these favorable conditions to flower and mature its seed before the pall of summer heat and drought descends upon the desert. With their task complete, the parent plants wither and die. Their ripened seeds are scattered over the desert to await the coming of winter rains for the opportunity to cover the desert with another multicolored but short-lived carpet of foliage and bloom.

The one-season ephemerals do not limit themselves to the winter growing period alone. From July to September, there are spotty thunder showers that deluge parts of the desert while other areas, not so fortunate, remain parched and dry. Where rain has fallen, another and entirely different group of plants, called the summer ephemerals find ideal conditions for growth and take their turn at weaving a desert carpet. Their seeds have lain dormant over winter. These summer "quickies" are plants that normally flourish during the winter rainy season farther south in Lower California and Sonora, Mexico. Saguaro National Monument is doubly fortunate in that it lies within a section of desert having not only its own year-round vegetation, but also summer flowers "borrowed" from its eastern and western neighbors for winter use, and from the winter wildflower gardens of its southern neighbors for summer decorations.

The short-lived leafy plants of summer and winter have found that they can compress their entire life activity into 6 to 12 weeks when conditions are most suitable. Thus, they can escape all the rigorous periods of the desert climate by living for 8 or 9 months in the dormant seed stage. Some of the spectacular and colorful flowers of the monument are among these ephemerals that survive desert conditions by escaping them. It must be remembered that when drought conditions or abnormally cold spring weather upset the norm, response of ephemeral plants is greatly restricted. If suitable conditions do not develop during the season for growth of a particular kind of ephemeral, its seeds will simple wait a year or more until conditions are favorable for growth.

Early spring ephemerals climax their show in March. From late February to mid-April they are completing their growth and putting forth the precious seeds that will assure survival for the next generation. At the head of this parade of the flowers in the monument is a purple-blossomed immigrant from the Mediterranean, the now thoroughly naturalized, FILAREE (Erodium cicutarium). In addition to the small purple flowers which may appear as early as January, the conspicuous "tailed" fruits almost always attract attention. When dry, they are tightly twisted, corkscrewlike; when damp they uncoil, forcing the needle-tipped seeds into the soil.

INDIAN WHEAT (Plantago purschii) is among the first plants to lay its green carpet over sandy spots on the desert floor following short winter days. The tan-colored individual flower heads are inconspicuous, but their numerous, close-growing spikes form a thick, luxurious pile-like ground cover. The countless tiny seeds are eagerly sought each spring by coveys of Gambel's quail; they were formerly also harvested by Pima and Papago Indians.

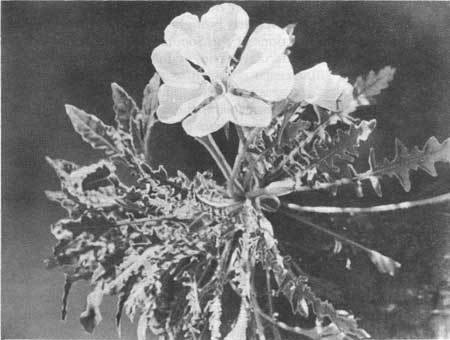

Among the most common and delicately beautiful of the early spring ephemeral plants are the SUNDROPS (Qenothera sp.). The large ground-hugging blossoms, with tissue-paper petals either white or pale yellow, open at night, to droop and close soon after sunrise. Usually found in sandy arroyos or open flats, these flowers of the evening primrose family sometimes create a mass display, but more often appear as individual plants scattered among desert perennials such as cholla cactus.

Sundrops (evening primrose). |

Often associated with sundrops along sandy washes, clusters of pink-flowered SAND VERBENAS (Abronia villosa) are conspicuous as early as February. They are sometimes found in solid patches, but also mingle with other spring flowers to produce a gay pattern of color in open, sunny locations.

DESERT CHICORY (Rafinesquia neomexicana) is somewhat like the common yellow dandelion but is longer stemmed and less coarse. Its white or butter-yellow blossoms make it one of the noticeable spring annuals in the desert. It rarely grows in pure stands but appears in conspicuous clumps among other short-lived plants.

Somewhat similar in appearance to the desert chicory is WHITE TACK-STEM (Calycoseris wrightii), one of the handsomest of the spring quickies. It is usually found on dry, rocky hillsides with white, or rose-colored flowers. Its name is derived from the presence of small glands which protrude much as would tiny tacks partially driven into the stems.

Following abnormally wet winters, FIDDLENECK (Amsinckia intermedia) covers patches of sandy or gravelly soil with a dense growth of bristly erect plants. These bear tight clusters of small yellow-orange blossoms arranged along a curling flower stem resembling the scroll end of a violin or fiddle, hence the name. This plant prefers the same growing conditions as creosotebush, frequently forming a dense, though short-lived, growth around the bases of these shrubs.

Associated with fiddleneck and creosotebush, SCORPIONWEED (Phacelia crenulata ambiqua) adds its violet-purple blooms to the spring flower display following winters of above-normal precipitation. The name is derived from the curling habit of the blossom heads which may remind the observer of the flexed tail of a scorpion. Touching the plant may cause skin irritation in susceptible individuals. Unfortunately, scorpionweed is also widely known as wild heliotrope thus contributing to the confusion engendered by duplication of popular names. The plant properly called WILD-HELIOTROPE (Heliotropium curassavicum) is similar in general appearance, but the flowers are white to pale purple and their odor more pleasing than that of the scorpionweed. Wild-heliotrope, or quailplant, is another of the early spring ephemerals, but under favorable conditions, where soils are moist, it may continue to live and bloom throughout the year.

Very common on sandy locations and quite noticeable because of its showy long-stemmed, large, yellow, circular flowers, the DESERT-MARIGOLD (Baileya multiradiata) helps to open the spring blossoming season. Where moisture conditions are favorable, plants may continue to bloom throughout the summer and well into autumn. Sometimes during the hottest, driest time of the year, desert-marigolds are among the very few blossoms brightening the desert floor. Their bleached, papery petals persist for days after the flowers have faded, giving the plant the name paper-daisy.

THE PAPERFLOWER (Psilostrophe cooperi) is not easily confused with the desert-marigold because of its short stems and its habit of growing in dense, dome-shaped clumps covered with 3- to 6-petaled yellow flowers. They sometimes continue to bloom throughout the entire year. In common with the desert-marigold, the petals of the paperfiower bleach and dry and may remain on the plant weeks after the blossoms have faded.

Although all of the species previously discussed contribute to the early spring floral display that has brought fame to Saguaro National Monument and other sections of the Sonoran Desert, the majority of them do not grow in spectacular masses as do some of the other winter short-lived plants.

Among the pre-season ephemerals is the tiny BLADDER-POD (Lesquerella gordoni). This low-growing annual member of the mustard family begins to cover open stretches of desert with a yellow blanket in late February or early March following wet winters. Bladder-pod is usually found in pure stands surrounding islands of cholla, creosotebush, and palo verde. However, bladder-pod also mingles with other spring ephemerals where it is promptly submerged by the ranker, taller-growing, more conspicuous annuals.

Similar in growth habit to the bladder-pod, PURPLE MAT (Nama demissum) is a small plant that produces large, reddish-purple blossoms making a spectacular show in pure stands, although the patches are usually quite small. When growing singly or mixed with other plants, this exquisite little flower is easily overlooked.

The tiny sunflower-like GOLDFIELDS (Baeria chrysostoma) is also similar to the bladder-pod in its low growth and consequent likelihood of being dominated by taller plants. Even so, it plays a part each year in the spring flower parade, sometimes carpeting extensive areas with bright-yellow flowers.

The bright-yellow GOLD-POPPY (Eschscholtzia mexicana) competes with filaree for the lead position in the spring flower parade, and almost every year captures top honors for its lavish and spectacular splashes of color. It covers wide sections of desert with its "cloth of gold," but in the monument, it rarely develops into a mass display because of the irregularity of the terrain and the abundance and variety of other vegetation. In places, it mixes with such other brightly colored annuals as the purple OWLCLOVER (Orthocarpus purpurascens palmer) and the blue-to-indigo LUPINES (Lupinus sp.) to form a gay and varied patchwork of color.

Illustrating one of the interesting phases in evolutionary variations among plants, the lupines are represented by several kinds which are able to survive and prosper in the desert. Some of these lupines are annuals of the quickie type which help to glorify the desert with their massed colors for a few short weeks. Others are perennials with a life cycle of several years. Some of these longer-lived species join with the ephemerals in the spring flower show, while others are more leisurely in approaching their blossoming time. All of them have developed devices for withstanding or avoiding the periods of the year when unendurable conditions prevail.

In this group of plants with species representing both the drought-escaping and drought-evading types are the GLOBE-MALLOWS (Sphaeralcea sp.). These vary in size from the small annuals (S. coulteri and S. emoryi) 5 or 6 inches high, whose blossoms paint the sandy desert flats with shades of apricot, bright yellow, and rich red from February to April; to coarse, woody-stemmed shrubs 4 or 5 feet tall blossoming throughout the year. These perennials along with hundreds of others, a number of of them of tree size, form a second major group of non-succulent desert dwellers.

|

|

|

|

|

Last Modified: Sat, Nov 4 2006 10:00:00 pm PST |