|

SAGUARO National Park |

|

Adaptation of Plants to a Desert Environment (continued)

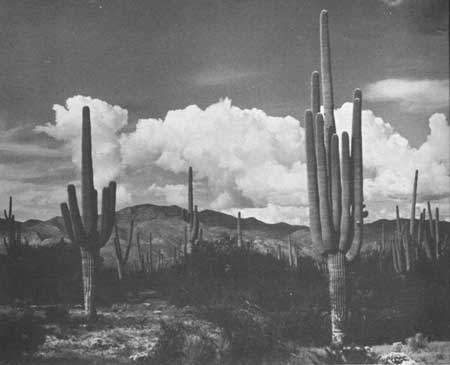

THE SAGUARO—MONARCH OF THE MONUMENT

Of the 27 species of cactus recorded in Saguaro National Monument the giant SAGUARO (Carnegiea gigantea) holds the center of interest. From the visitor standpoint all the other plants, no matter how bizarre in appearance or peculiar in their living habits, are just so much stage scenery for setting off the star of the desert drama. For size, this vegetable mammoth tops all other succulents of this country; heights of more than 50 feet and weights in excess of 10 tons have been recorded. And there have been specimens with more than 50 arms or branches. Although no accurate method of determining age has been devised, it is estimated that an occasional veteran may reach the two-century mark.

Desert area and Tanque Verde Mountains in background. |

Structurally the giant cactus is well adapted to meet the stern requirements of its habitat. Its widespread root system, up to 60 or 70 feet in diameter, lying close to the surface of the ground securely anchors and holds the heavy plant erect. The root system collects and channels to the main stem any moisture that may penetrate the topsoil. The trunk and branches have a cylindrical framework of long slender poles or ribs fused at the constricted base. This skeleton supports the mass of pulpy tissue, the whole being covered with tough, spinebearing skin. Numerous vertical ridges, like the pleats of a huge accordion, permit the stems and branches to expand in girth as the tissues swell with water during wet weather and to shrink during times of drought.

So efficient is the saguaro's water-storage system that, even after years of extreme drought, the plant still has enough moisture in reserve to enable it to produce flower buds. The buds appear in crowded clusters at the tips of the branches, a few opening each night over a period several weeks, usually in May. Petals are waxy white with blossoms up to 4 inches in diameter. This beautiful blossom is the State flower of Arizona. The egg-shaped fruits mature in June and July, splitting open when ripe to reveal masses of juicy, deep-red pulp filled with tiny black seeds. Pulp and seeds are consumed by several kinds of birds, especially white-winged doves. Fruits that fall to the ground are promptly eaten by rodents and other animals. Pima and Papago Indians still harvest the fruits in some parts of the desert.

Although billions of saguaro seeds are produced yearly in the extensive stand in Saguaro National Monument, only a very few find favorable locations for germination and growth. Since it requires a shaded location with moisture-retaining humus in the soil, a saguaro seed must come to rest beneath a desert shrub or tree with low leafy branches. Woodcutting, livestock grazing, and other activities of man have done much to reduce the expanse of desert suitable for normal saguaro reproduction. It has been estimated that only one out of each 275,000 saguaro seeds produces a plant. Early growth is extremely slow, a 2-year-old saguaro being only one-quarter of an inch in diameter, and a 10-year-old plant 4 inches high.

Mankind has inadvertently endangered the future of the cactus forest in other ways. For example, rodents rely upon the tender tissues of young succulents as a source of vital moisture. Any expansion of the rodent population increases the hazards of life for small saguaros and reduces the number able to survive. Snakes, coyotes, hawks, and owls are among the chief predators that keep the rodent population within bounds. By killing snakes and hawks, and by waging poison campaigns against coyotes and foxes, man has lessened nature's control over rodent populations. Among the unexpected results of extensive predator reduction projects of the past is the present serious lack of young saguaros to replace today's mature stands.

|

|

|

|

|

Last Modified: Sat, Nov 4 2006 10:00:00 pm PST |