|

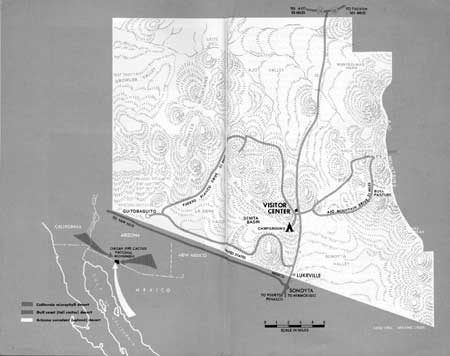

ORGAN PIPE CACTUS National Monument |

|

Animals (continued)

Animals of the Open Desert and Its Drainage Channels

Like the doves that assemble daily at Quitobaquito for water, many mammals and birds travel a considerable distance to springs, tanks, or seeps. Others, however, require less moisture, drinking infrequently or meeting their requirements from the moisture within the plants or animals that they eat. Several, of which the kangaroo rat is an example, obtain their water through processes of metabolism within their bodies by means of which dry foods are converted to essential moisture.

Kangaroo rats are nocturnal, remaining in their burrows during daylight hours. These burrows are frequently seen in open desert country, a number of openings often perforating a mound of earth around the base of a creosotebush. By remaining quietly underground during periods of high temperature and low humidity, kangaroo rats and some other rodents conserve moisture, escape heat, and avoid the searching eyes of hawks, coyotes, and other diurnal predators. They cannot, however, thus escape badgers, whose heavily clawed forefeet and powerful shoulders enable them to dig out their prey.

Kangaroo rats have small forefeet, which they use for digging and for stuffing food—principally seeds and other plant materials—into their fur-lined cheek pouches. Their hind legs and feet are large, enabling them to cover the ground in huge leaps when pursued by owls, foxes, snakes, and other nocturnal predators—their chief enemies.

In hot weather, snakes, including rattlers, do their hunting at night. Remember this if you are afoot in the desert after dark, and use a flashlight to illuminate the path ahead. During the day these reptiles remain quiet in deep shade or in rodent burrows, since they cannot endure extreme temperatures.

Another desert inhabitant, numerous on the creosotebush flats, is the round-tailed ground squirrel, which burrows in the sandy soil and climbs into shrubs and small trees to gather seeds and other plant parts. Usually active during the day, these squirrels disappear for several weeks during the hottest part of the summer, remaining inactive within the network of their underground tunnels. They also remain below ground during the coldest part of winter, although they may not hibernate. Slender-bodied snakes, such as the western red racer, are able to enter the burrows and feed on the young.

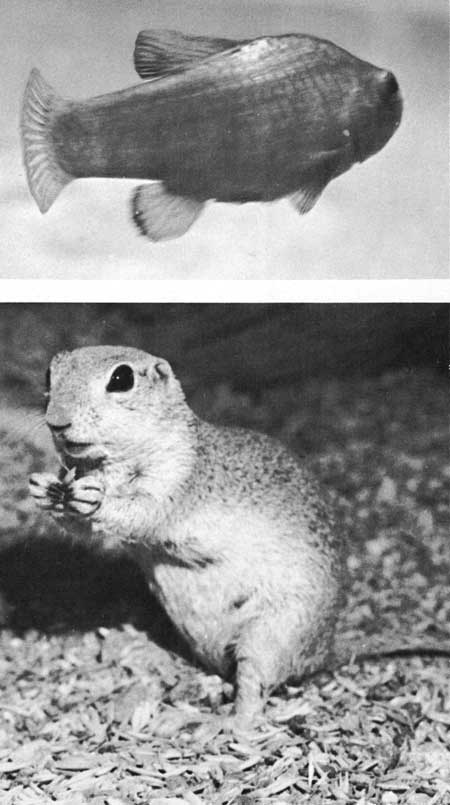

The rare desert pupfish (above) lives in the pond and springs at Quitobaquito. Round-tailed ground squirrels (below) are usually found on creosotebush flats, where their tan coats blend with the brownish soil. |

Airborne enemies of the ground squirrel include Swainson's hawks, golden eagles, and red-tailed hawks, which keep a keen watch of the ground as they ride the rising air currents over desert flats and bajadas. These big birds also feed on gophers, snakes, lizards, rabbits, and large insects such as grasshoppers.

Jackrabbits range widely in the monument and are not limited to any specific habitat. They are frequently seen in the evening or early morning on the open flats, where sparse vegetation makes them more readily visible. During the heat of the day they seek shade beneath shrubs and trees that border desert washes. Foxes, coyotes, hawks, owls, and other furred and feathered hunters prey upon them. They obtain much of their moisture from their plant food, sometimes gnawing into cactus stems to get at the succulent tissues.

An animal of the grasslands, the pronghorn is rare in the desert, but it is quite possible that you may sight one of the small bands that range over the western part of the monument and the adjoining Cabeza Prieta Wildlife Refuge. Fleet of foot and trusting to its sight to warn of an enemy's approach, the pronghorn prefers open country. It is known to eat saltbush and ephedra; it also eats pricklypear stems for the moisture they contain.

Sometimes at night the kit fox is seen crossing open flats or hunting among the shrubs bordering desert washes. This large-eared fox is the smallest of the canine predators. Subsisting principally on kangaroo rats, rabbits, and other nocturnal mammals, the kit fox also eats insects and an occasional reptile.

The sidewinder is a small gray rattlesnake, readily recognized by the conspicuous hornlike process over each eye which serves as a protecting ridge when the snake lies almost buried in the sand. This poisonous reptile can be identified by the looping motion which enables it to travel with ease over the sandy soil of its favored habitat. The sidewinder is rarely encountered because in warm weather it is abroad only at night. Its occasional tracks, looking like a series of parallel "J's" in the sand, are usually the only evidence of its presence. Sidewinders eat small mammals, nestling birds, and lizards.

Among the common lizards of the creosotebush environment is the insect-eating checkered whiptail, or racerunner, often found on the open flats far from water. Less common is the crested lizard, or desert iguana, which, when disturbed, usually runs a considerable distance to disappear into a bush from which it emerges on the opposite side. If chased, it displays an uncanny knack of keeping a bush between itself and its pursuer. Food consists principally of plant material, including leaves, flowers, and fruits. Lizards and some snakes obtain necessary moisture from the body juices of their food.

(click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

One of the few birds which nest on the open flats is the attractive black-throated sparrow, found all year in the monument and identified by its black throat and white facial stripes. It also nests on bajadas among chollas and other plants.

Birds are more numerous in the sparsely vegetated creosote-bush flats in winter than in summer. Many of the smaller birds, such as the white-crowned and Brewer's sparrows, winter in the desert areas along the Mexican border, migrating northward in spring to their nesting grounds in the Great Basin and Rocky Mountain States. They find insects and plant food among the winter ephemerals that spring up on the open ground between creosotebushes. Other winter residents that go north in the spring are lark buntings, which usually travel in small flocks, sage thrashers, and chipping sparrows.

The thick cover, shade, and insect-attracting blossoms and fruits of mesquite and paloverde thickets form special environments along the banks of dry desert washes. Abundant vegetation furnishes food, sanctuary, and nesting sites for resident birds, as well as protected travel avenues for transient species. Many mammals and reptiles make use of them as hunting grounds or hiding places.

Desert cottontails are numerous throughout the desert country and up into the canyons and mountains wherever food plants are abundant and there is suitable brush for cover. These rabbits take advantage of the tender growth of both winter and summer ephemerals, resorting to twigs and bark of shrubs and trees and the stems of succulents when fresh growth is unavailable. They are preyed upon by snakes, hawks and owls, coyotes, bobcats, and foxes; hence they remain close to the protective cover of shrubs, thickets, and rocky outcroppings.

For much the same reasons, Gambel's quail frequent mesquite thickets where insects are plentiful and where their roosts are protected from winged and furred night predators. From these thickets they can range into the flats and bajadas to feed on perennial seeds or the greenery of alfilaria, spurge, spiderling, and other desert ephemerals.

Feeding on insects, nestling birds, small rodents, and fruits, the ringtail is a night prowler. It frequents the same thickets along dry washes and rocky canyons as the quail and the cottontail. A relative of the raccoon, the ringtail is easily recognized by its large ears and eyes and its long, fluffy, banded tail.

Consider yourself fortunate if you happen upon a band of peccaries, which are fairly abundant and are believed to be on the increase in the monument. They range through mesquite and cactus thickets during much of the year, principally in search of cactus stems and fruits, but also of herbs, succulent roots, mesquite beans, and insects. These piglike animals, commonly called javelinas in the Southwest, sometimes summer in mountain canyons, favoring oak brush where acorns later provide a welcome change of diet.

Insects are found everywhere throughout the desert. During the blossoming season, they are especially numerous along the washes where mesquite, catclaw acacia, paloverde, and tesota trees are laden with nectar-producing flowers. Among the hundreds of species of insects whose wings fill the air with the hum of activity, honey bees are much in evidence. Not native to the monument, they have become naturalized here and have established colonies in caves and crevices in the basalt cap rock. Bees and other insects may be found in numbers around seeps and springs where they obtain water, but they get much of their moisture from the nectar of flowers and the sap of plants.

The body fluids of insects in turn provide vital moisture for birds and for reptiles, such as the Arizona zebra-tailed lizard, which frequent sandy washes. Extremely sensitive to temperature changes, these lizards bury themselves in the sand at night. During early morning and late afternoon, they are active in the sunshine, but in the heat of the day they seek the shade of paloverde and mesquite trees and shrubs that line the flood-stream channels. When motionless, they blend inconspicuously into their surroundings. If disturbed, they curl their black-banded tails above their backs and race away. L. M. Klauber, formerly of the Zoological Society of San Diego, considers this species the speediest reptile of the desert. He has clocked it traveling at 5 times the speed of the fastest snake.

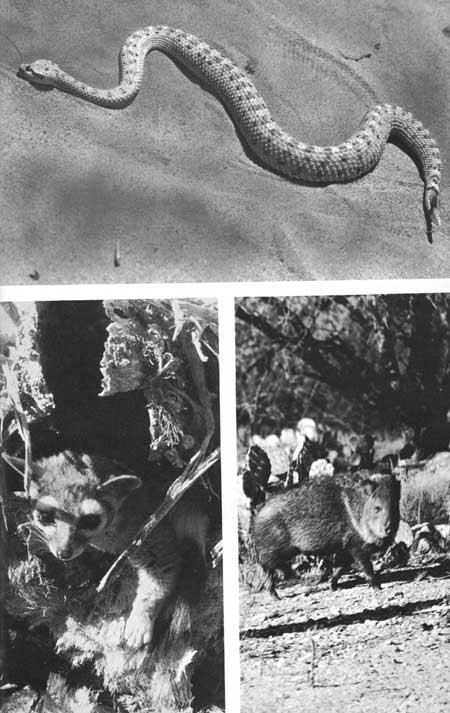

It takes some luck to see this trio of monument animals. The horned rattlesnake, or "sidewinder," and the ringtail (lower left) hunt by night. Peccaries, believed to be increasing, range in bands through mesquite and cactus thickets. |

The Sonora spiny lizard is usually found on the trunks or branches of trees, but sometimes it descends to the ground to forage for insects, ready at any moment to rush for cover at the approach of an enemy.

In addition to the many birds which frequent mesquite and paloverde thickets in search of food or shelter, a number of species, including doves, find nesting sites in the trees and shrubs along the borders of desert washes. Among the smallest of these birds are the vivacious verdins and the sprightly gnat-catchers. The former, identified by the dull-yellow head and reddish-brown shoulder patch, construct globular nests about the size of a large coconut, with the entrance partially underneath. Verdins eat insects when they are available and subsist on fruits and seeds in winter.

Not common, but so colorful as to attract immediate attention, are the cardinal and the pyrrhuloxia, both of which are year-round residents. Both have conspicuous crests. Cardinals are brighter red and less chunky in appearance than pyrrhuloxias, which are a blend of red and gray.

|

|

|

|

|

Last Modified: Sat, Nov 4 2006 10:00:00 pm PST |