|

Volume XX - 1954

Crater Lake Waters

By C. Warren Fairbanks, Assistant Park Naturalist

Each year, some three hundred seventy thousand visitors make their

way to Crater Lake National Park. While their reasons for coming, and

what they see and remember of the park, are doubtless as many and varied

as are the visitors themselves, it is safe to say that, with very few

exceptions, the center of their interest is Crater Lake itself. These

beautiful waters - their color describable only as Crater Lake Blue --

rest in the top of an ancient mountain whose summit was destroyed about

6,500 years ago.

An occasional visitor will step up to the rim, take a quick look,

and say to his companion, "Well, we've seen it. Let's go." More often,

however, the lake excites curiosity and prompts questions such as, "How

did it come to be?," "How deep is it?," "How cold is it?," "Are there

fish in the lake?," "Does it have an outlet?" and, "Does the water level

vary?" The one of particular interest here is the last.

Although Crater Lake, deepest in the United States, was first seen

by white man in 1853, dissemination of information was then so limited

that two later, independent "discoveries" were made -- in 1862 and 1865

(Runkel, 1953). Also, no serious scientific investigations within the

area eventually to become Crater Lake National Park were made until the

visit of the Joseph Diller party in the summer of 1886. At this time,

the first Geological Survey map was constructed, soundings and

temperatures of the lake waters were taken, and foundations were laid

for what is now called the geologic story of Crater Lake. It was then

that the deepest sounding of 1,996 feet was made.

Since that time, other soundings -- notably those of John E. Doerr

in 1939, then Park Naturalist at Crater Lake National Park and currently

Chief Naturalist for the National Park Service -- and studies of lake

levels have been made. The earliest water-level records, aside from

Diller's of 1886, are largely obscure and of somewhat uncertain

accuracy. Several are derived from names and dates painted by occasional

visitors on rocks at the water's edge. Some of these, however, are more

or less readily relatable to later-established, known elevations and can

be accepted with some validity.

The early picture is further confused by differences, unresolved by

data presently available, in basic elevations established by the Diller

party as compared with those on the current topographic map. For

example, the lake-surface elevation, a figure subject to various types

of fluctuations, was recorded for 1886 (Diller and Patton, 1902) as

being 6,239 feet above sea level. This amounts to a difference of

sixty-two feet from the 6,177 feet given on the most recent topographic

map. Furthermore, all elevations of known stable points are of a

magnitude greater than those on this 1946 edition - as well as on other

available maps dating later than 1886. The disparities on specific

points vary from as little as twelve feet to well over one hundred feet.

It is understood, however, that elevations of many points throughout the

western United States have been revised downward since Diller's work. In

order to arrive at a comparable figure, the differences of seven

prominent rim points were averaged. This figure, seventy-one feet, was

then subtracted from the 6,239 feet given for the lake level. The result

is 6,168 feet, a value that falls nearly in the middle of the observed

range of lake levels.

The first water gage on the shore of Crater Lake was erected for the

Mazamas, a mountaineering club of Portland, Oregon, on August 22, 1896

(Diller and Patton, 1902). Diller states that it "was made of a board 5-

3/4 inches wide and 10 feet long, with scale subdivided to tenths of a

foot. It was nailed to a log extending from the shore into the water,

and zero of the scale was placed just 4 feet beneath the water surface,

. . . Fearing that this fragile gage might not escape accident from

rolling stones and sliding snow, W. W. Nickerson, of Klamath Falls, was

requested to insert a bolt in a cliff near the gage and carefully

determine the height of the bolt above the water and read the gage."

The Nickerson bolt, a copper pin, was placed in position on

September 25, 1896. The precaution was a good one, as the Mazama gage

was cast adrift that winter, and the record book, contained in a copper

box, was not recovered until five years later, on August 13, 1901. Two

of Diller's associates found it in Danger Bay in five feet of water,

three and one half miles from Eagle Cove, the original location (Diller

and Patton, 1902) The records were intact.

Diller, by referring to the record book, then painted a scale with

the same zero point on a nearby rock face and inserted a pin, now known

as the Diller Pin and still in place, at a point eight feet above zero

point - four feet above the water level at the time that the original

gage was installed. Diller (Diller and Patton, 1902) relates numerous

water-level readings, including several incidental ones previously

mentioned, to the Mazama gage. The earliest of these was September 10,

1892, when the water stood at 4.142 feet. The lowest such record

reported by Diller was for September 26, 1893, when it was 2.52 feet, or

1.48 feet lower than the 1896 figure.

Since that time, four other gages -- including the most recent,

placed October 3, 1952 - have been installed and numerous readings

taken, although not with complete regularity. It is evident that the

earliest records were not related to elevations as were those of later

years. Young (1952) indicates that in 1908 a U. S. G. S. benchmark,

giving an elevation of 6,179 feet, was set near the water's edge. It was

from this benchmark that the levels of August 19, 1916, taken by F. F.

Henshaw, District U. S. G. S. Engineer, were established. On the basis

of his findings, the zero (datum) for the Mazama gage is placed at

6,173.64 feet above sea level. This places the oldest known related

level (September 10, 1892) at 6,177.78 feet, and the 1896 level, when

the Mazama gage was installed, at 6,177.64 feet. It is interesting to

note here (Young, 1952) that the lake level reported by Diller --

6,178.545 feet, July 1, 1901 - records the lake at its maximum observed

stage.

Records of lake level compiled by Ranger W. T. Frost (1937a, 1937b)

indicate the level as remaining fairly constant. The greatest annual

variation during the period of years from 1908 to 1913 was only 1.55

feet. No records were shown for the war years, 1914-1917. In 1918 there

appears the beginning of a prolonged decline, which may actually have

begun in the four previous years.

Frost's notations carry through the year 1936 and show a general

decrease in precipitation, correlated with the drop in lake level. He

stated that the "Lake level is falling at an average rate of .51 foot

per year. (Estimated from figures over a 26 year period)." He also

stated that the average seasonal variation was 1.55 feet. In this

connection, Diller (Diller and Patton, 1902) states that the annual

"oscillation is limited to about 4 feet." He says further that "the

rising and sinking balance each other so that the lake maintains in

general the same level." This appears to be essentially true.

It seems possible that the annual fluctuation quoted from Frost may

be somewhat less than total, since the lake is at its highest -- usually

in May or June -- when it is least accessible for obtaining data. This

appears to be the reason for Diller's estimate of a maximum of four

feet. Paul Herron, boat operator and engineer for the Crater Lake

National Park Company, reported that the lake level for the 1954 season

remained fairly constant at 6,176.9 feet during the first twenty days of

June, after which it began to recede gradually. The last reading taken

prior to the time of this writing was made on August 18; this report was

6,176.26 feet, representing a drop of 0.64 foot in approximately two

months. The lowest level, however, should be expected at sometime in

October, after the beginning of fall rains and snows.

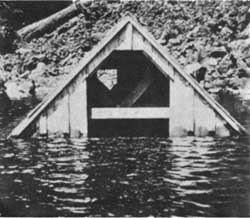

In the fall of 1942, the sills of this 10-foot high

boathouse stood 18 inches above the lake water level.

From aKodachrome, taken in August, 1954, by C. Warren Fairbanks

|

Recession of the lake level during these years, 1918-1936, continued

until 1940, when the all-time low of 6,162.3 feet was recorded (Young,

1952). From that date until the present, Crater Lake has risen steadily,

for an observed total of 14.6 feet in fourteen years -- an average of

1.043 feet per year. The level this year falls within the range of high

levels which extended from the 1890's through 1913.

As has been mentioned previously, the highest observed level was

recorded by Diller in 1901. This figure of 6,178.545 feet, when

considered together with the 1940 low, indicates an all-time observed

fluctuation of 16.245 feet.

There is, however, some evidence of a higher level at some time in

past. Gordon Hegeness (Williams, 1942), formerly a Ranger Naturalist at

Crater Lake National Park, found a deposit of diatoms -- microscopic

water plants which have siliceous walls -- on Wizard Island,

approximately fifty feet above the water level. Williams uses this

evidence to assume a former high level of that approximate magnitude.

The location of this find apparently was not recorded, and analysis of

that material to determine its significance has not been possible.

Investigations carried out this summer, however, have contributed

significantly to our knowledge on this point; the results are reported

upon elsewhere in this issue (Rowley and Showalter, 1954).

There is some evidence from another source which indicates a

slightly higher level in the past. A definite line formed by the

drowning-out of lichens -- primitive plants which can gain a foothold on

bare rock faces - is observable a few feet above the present water

surface.

Young (1952) uses field notes of F. F. Henshaw and of J. S. Brode,

another former member of the naturalist staff at Crater Lake National

Park, to arrive at the figure of 6,180.9 feet as the probable highest

level of the lake, at least in recent decades.

Thus it may be seen that the surface level of Crater Lake fluctuates

in response to both seasonal and climatic variations. The former,

resulting primarily from differences in the amounts of precipitation and

run-off at various times of the year, occur relatively rapidly but are

moderate in range. The latter operates over longer periods of time but

are ultimately responsible for greater extremes.

References

Diller, Joseph S., and Horace B. Patton. 1902. The Geology and

Petrography of Crater Lake National Park. Washington, Government

Printing Office. 167, iii pp.

Frost, W. T. 1937a. Snowfall -- precipitation and lake levels.

Crater Lake National Park Nature Notes 10(1):3-7.

-----. 1937b. Errata. Crater Lake National Park Nature Notes

10(3):43.

Rowley, John R., and Wendell V. Showalter. 1954. Wizard Island, an

index to the past? Nature Notes from Crater Lake 20:26-31.

Runkel, H. John. 1953. Crater Lake discovery centennial. Nature

Notes from Crater Lake 19:4-9.

Williams, Howell. 1942. The Geology of Crater Lake National Park,

Oregon. Carnegie Institution of Washington Publication 540.

Washington, D. C., Carnegie Institution of Washington. vi, 162 pp.

Young, Charles A. 1952. Report on Crater Lake gages and elevations

from 1892-1951. (MS. in Naturalist Files, Crater Lake National Park

Naturalist Office).

|