|

Volume XXVIII - 1997

An Offering in the Forest

By Steve Mark

Winter can last for more than seven months at Park Headquarters. A

sign of the coming of spring appears when enough snow has melted to

reveal a figure known as the Lady of the Woods. When the snow finally

disappears, which is usually in June or July, visitors can take a short

trail located behind the Steel Information Center to view the three foot

high sculpture. Chiseled from a boulder, this unfinished work of art

blends almost perfectly into a subalpine forest of mountain hemlock. It

will be 80 years old this October and shows a few signs of age. The most

noticeable is pitting in the once smooth volcanic rock, but there are

also some details that have begun to fade with time. In spite of its

inevitable decay, the sculpture is still striking and should remain

recognizable well into the next century.

Oddly enough, the Lady of the Woods was its creator's first attempt

at sculpture. At the time of its carving, Earl Russell Bush was a 31

year old medical doctor who attended to the road crews that built the

first rim drive around Crater Lake. The season's work had largely ceased

by the end of September 1917, and he found himself with almost two weeks

at his disposal. Bush left the park on October 20th, having chisled and

hammered a recognizable form on the hard rock. He worked from memory

and, several years later, tried to explain what possessed him:

Earl Russell Bush and the Lady of the Woods,

1954.

NPS photo by C. Warren Fairbanks.

|

"This statue represents my offering to the forest, my

interpretation of its awful stillness and repose, its beauty,

fascination, and unseen life. A deep love of this virgin wilderness has

fastened itself upon me and remains today. It seemed that I must leave

something behind...if it arouses thought in those who see it, I shall be

amply repaid. I shall be satisfied to leave my feeble attempt at

sculptural expression alone and unmarked, for those who happen to see it

and who may find food for thought along the lines [of what] it arouses

in them individually. It would be sacrilege to assign a title and

decorate it with a brass plate. "

By the 1930s the statue acquired both a title (suggested by Fred

Kiser, the photographer, who seemed to always be looking for different

ways to promote the park) and a sign made of wood with raised lettering.

The idea of leading visitors there with a trail came under attack for

the first time in 1930, and is an objection which has been voiced

several times since then. Not by visitors, nor through conservation

groups, but by park employees who thought the sculpture did not belong

in a "natural" area. To them, such artifice had no place even at Park

Headquarters, where rustic architecture and naturalistic landscape

design blend aesthetics with function. Just as with stone masonry (which

is used on buildings and evident in walls, steps, curbs and even

drainage features), the carving constitutes an attempt to design with

nature. The only difference is that the sculpture's functional aspects

may not be immediately apparent to all who view it.

Whereas the function of most built features at Park Headquarters has

been put in terms of visitor services (information, restrooms) or

support facilities (employee housing, offices, equipment storage), the

Lady of the Woods serves to instruct and inspire. The sculpture can

speak to change, because 80 years ago Park Headquarters looked

considerably different than it does today. When Bush made his carving in

1917, there were only three log buildings and a barn with no attempt at

year round occupancy of the site. Less than a decade later the National

Park Service began building a headquarters where the road camp had been,

something which expanded over time to impinge on the sanctity of the

forest that Bush once knew.

The Lady of the Woods is not, however, a merely antiquarian artifact

(where the past is separated from the present) because NPS landscape

architects incorporated it within an exceptionally coherent site design,

listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1988 as the Munson

Valley Historic District. Despite the recognition, designed landscapes

cannot be frozen in time and compromises remain apparent -- most notably

in the NPS having to utilize Park Headquarters for winter operations.

This can be seen even along the 400 foot trail to the Lady of the Woods.

Not only have the Messhall and Meathouse been adaptively reused (for

ranger operations and a trail cache, respectively), but looming in the

distance between them is the recently constructed maintenance shop -- an

especially unartistic and slavish example of form following function

when contending with snowfall.

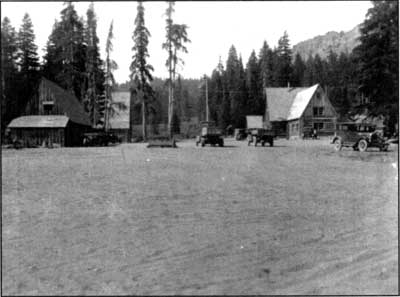

Park headquarters at the time when Bush carved the

Lady of the Woods, ca. 1925.

NPS photo.

While change is important, character-defining features of the

historic district and (in particular the Lady of the Woods) are more

significant as representations of continuity. This type of continuity

pertains to how parks evolved as a cultural expression of interaction

with a certain setting or environment. Parks began as simple enclosures,

intended as places where the nobility exercised exclusive rights to hunt

game animals. During the 17th and 18th centuries parks fused with

ornamental gardens, the latter having originated in the Ancient World

from an urge to manipulate nature and create pleasing effects. Features

of the garden (such as plantings which imitated growth in the wild,

walks, and statuary or other structures built to evoke introspection in

those allowed access) followed Classical models at first and then became

more "natural" as the desire to emulate landscape paintings spread

throughout western Europe. The English were especially adept at creating

"landscape gardens" and developed a vocabulary for enjoying the

"picturesque" surroundings which were contrived to appear more natural

than Nature itself. When parks became public as a response to 19th

century urbanization resulting from the Industrial Revolution, the

private landscape gardens of the gentry and a newly rich class of

merchants thus became models for how to socialize a broad spectrum of

citizens by bringing them into contact with the perceived benefits of

nature.

Those familiar with the landscaped parks brought their vocabulary

with them when they went looking for "sublime" scenery. These people

followed their guidebooks and found monumental scenery which matched the

lighting effects employed by landscape painters to animate mountains,

forests, lakes, waterfalls, caves, or coastlines. Americans embraced

these aesthetic tastes at roughly the same time as the public park

movement came across the Atlantic. It is therefore no surprise that

public parks could encompass not only the countryside within or adjacent

to cities, but also the most sublime scenery, particularly where the

land remained in the Public Domain. National parks are really part of a

vast national estate, where a few of the most unusual features such as

Crater Lake can be protected for future generations to contemplate. By

seeing sublime landscapes as art, the prevailing taste allowed for

access but sought to minimize visitor impact.

Consequently, developments in the national parks have usually had

both functional and ornamental qualities, with the best being

subordinate and inspired by its surroundings.

Employees and visitors are now prevented by NPS regulations from

making artistic statements similar to Bush's, but the Lady of the Woods

is a rare window into the cultural patterns behind the origin and use of

national parks. Through this sculpture and rustic architecture elsewhere

in the park, it is possible to relate the story of how a collective

perception of nature developed through time and found expression in

gardens, parks, and finally sublime landscapes. I thought of this

inheritance and Bush's intent when these lines from J.M. Synge's

Prelude came to mind:

I knew the stars, the flowers, and the birds,

The grey and wintry sides of many glens,

And did but half remember human words,

In converse with the mountains, moors, and fens.

Reference: Richard M. Brown, The Lady of the Woods Revisited,

Nature Notes from Crater Lake 21 (1995), pp. 5-12.

|