|

Volume XXX - 1999

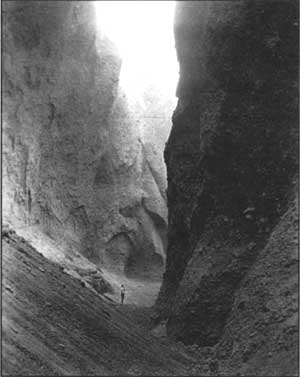

The Portals of Whitehorse Creek

By Steve Mark

Llaos Hallway is a portion of Whitehorse Creek where the stream has

cut through many feet of pumice on its way to Castle Creek, a tributary

of the Rogue River, The "hallway" is no different from other stream

canyons in the park, except for the fact its walls tower 125 feet above

a narrow gorge for several hundred yards. It is named for Crater Lake's

special guardian (called Llao or La-o by Klamath Indians)

who is thought to dwell in the underworld.

Hikers descend into Llaos Hallway by way of the stream channel, and

in one place have to place their feet on opposite sides of a chute. Any

journey there is made more interesting and perhaps uncomfortable when

there is water in the creek. Snow can linger until relatively late in

July, thereby inhibiting an early season trek to the Music Shell--the

culmination of most journeys down the hallway. The more adventurous, and

those with more than an hour or two, may wish to use Llaos Hallway for

entry into Castle Creek Canyon. It contains a number of oddly shaped

pinnacles rivaling the more renowned fossil fumaroles in Wheeler Creek

or Godfrey Glen. This makes for an interesting walk, whether upstream or

down. I remember a hike on Labor Day 1990, when three of us saw water

tinged with sulphur spouting from a canyon wall on our way to finding a

deer trail that led us out of what seemed to be an enclosed

wilderness.

Excerpt from USGS Quad Map.

It would, of course, be foolhardy to attempt climbing out of the

canyon on anything less than such a trail, given the unstable nature of

the walls. Wet feet and dirty clothes might be the worst things suffered

on such a trip, but Castle Creek and Llaos Hallway are not for those who

hike alone. So few people go there that an injured person by themselves

may not be found for weeks, especially if their vehicle is not parked

close at hand.

Llaos Hallway. NPS photo, ca. 1931.

|

Wearing good boots, along with a helmet during periods of rockfall

(which can last most of the summer in Llaos Hallway) are two good

precautions for those who want to explore this area.

To reach Llaos Hallway, find Whitehorse Creek (unsigned) located

about 3.5 miles west of the Annie Spring junction (Highway 62 and the

road to Crater Lake), or roughly 4.5 miles east of the park entrance

sign on Highway 62.

An unpaved parking spot north of the highway accommodates one

vehicle. It is less than 100 yards from the creek, around a small bend

if coming from Annie Spring. The forest here is an unremarkable mix of

lodgepole pine and mountain hemlock. Down wood obscures the largely

barren ground underneath the canopy, though pinemat manzanita can be

found here and there in the open pumice. Only in the drainages might

there be small bunches of dwarf huckleberry and occasional clumps of

moss, but most of the stream passing through Llaos Hallway is completely

barren.

The urgency of the few who hike into Llaos Hallway every year causes

them to overlook the area where Highway 62 crosses the creek. All the

passing motorist sees is a bend in the road, but this place once

represented a potential stopping point to early travelers, Soldiers

building a wagon road from Fort Klamath to Jacksonville in 1865 named

Whitehorse Creek, Their commander, F.B. Sprague, identified a spot lying

to the south of Highway 62 as "Soldiers Camp" where plenty of water

could be found, but little or no feed for horses, Observant visitors

will find a remnant water line along the stream south of the highway,

something that initially stumped a team doing archeological survey in

the summer of 1997. Where, we wondered, did this pipe go? Why was it

installed? We followed it several hundred yards upstream and obtained

little in the way of answers.

Discovery of a campground on the north side of Highway 62 in

1998 was unconnected with the ongoing archeological survey. It occurred

during an inventory of disturbed sites conducted by biotechnician Jamie

Halperin.

Hikers preparing for a trip into Llaos Hallway.

Photo by Steve Mark.

He not only solved the waterline mystery, but also found a standing

wood frame outhouse about 50 yards from Whitehorse Creek, Upon seeing

it, the outlines of a former automobile campground immediately began to

become clear to me, Privies and associated features usually function as

orientation points to occupation sites in archeology, but I walked

through the camp without seeing it. In retrospect, I never saw what

seemed to be the obvious in numerous journeys to Llaos Hallway.

The point of this story is that you often find only what you are

seeking. We now wanted to map the locations of old campgrounds,

especially those located along a 19th century wagon road that once

brought visitors to Crater Lake (see pp. 16-19 of the 1997 Nature

Notes). None of these camps are particularly rich in artifacts, but they

have distinctive characteristics reflecting patterns of travel and past

visitation when seen collectively. Even if the only physical remains

appear relatively subtle (generally in the form of blazed trees, pieces

of wire, or glass fragments), they contribute to the significance and

integrity of a road "system" now more than a century old. The

campgrounds on Whitehorse Creek can also remind present day visitors

that others have lingered here and perhaps embarked upon a journey to

Llaos Hallway. Since only a handful of people venture this way every

year, it is still possible to experience the same sense of solitude and

envelopment that has always captivated the adventurous only a short

distance from the road.

Steve Mark is a National Park Service historian who has been

the editor of Nature Notes from Crater Lake since its revival in

1992.

Drawing appeared in article titled "Haymaker,"

Nature Notes from Crater Lake, 5:3, September 1932.

|