|

Volume XXXII-XXXIII - 2001/2002

Fish in Crater Lake: Their Size and Number

By Scott Girdner

Ranger-naturalist Arthur Hasler showing a rainbow

trout to visitors in 1938. NPS photo.

|

Anglers who routinely 'wet a line' in Crater Lake have learned that

fishing success as well as the size of kokanee salmon and rainbow trout

in the lake can fluctuate dramatically from year to year. Analysis of

fish length and fish population size over the last 15 years provides

insight into the patterns of change and may help anglers appreciate the

ups and downs of fishing Crater Lake.

Crater Lake was naturally barren of fish until park founder William

Steel first stocked Crater Lake with trout fingerlings in 1888 to

"improve" recreational opportunities. Despite altering the lake's

natural condition, introductions of non-native fish continued until

1941, when stocking the lake ended. In all, five species of salmonids,

totaling nearly two million fish, were introduced to the lake over the

intervening 53 years. Brown trout (Salmo trutta), cutthroat trout

(O. clarki), coho salmon (O. kisutch), kokanee salmon

(O. nerka, a landlocked sockeye salmon), and several stocks of

rainbow trout (O. mykiss) including steelhead were introduced

during this period. Only the self-sustaining populations of rainbow

trout and kokanee salmon persist in the lake today.

Kokanee salmon. NPS photo by C. Warren Fairbanks,

1954.

|

Detailed annual fish population estimates using high-tech acoustic

systems were initiated in Crater Lake in 1996. The largest fish

population observed in Crater Lake since that time occurred during the

summer of 2000 when biologists estimated the total number of fish in

Crater Lake at 633,000—a density of 48 fish per acre. Lake Billy

Chinook near Bend, by contrast, is estimated to contain between 530 and

5500 kokanee per acre depending on the year. Coeur d' Alene Lake in

Idaho typically fluctuates around 1400 fish per acre. The lowest number

of fish in Crater Lake occurred in 1998 when only 8,400 (less than 1

fish per acre) were observed. Just two years later the fish population

in Crater Lake increased by an astounding 7450 percent!

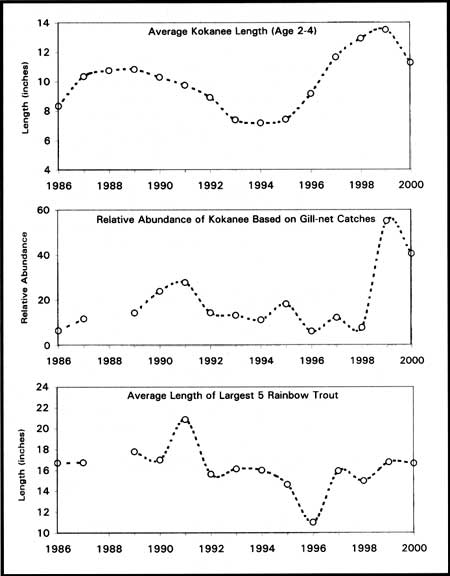

The relative abundance of kokanee has been monitored with gill nets

since 1986. Population size and the average length of individual kokanee

salmon cycles over a period of approximately ten years (see the first

two graphs in Figure 1). According to fisheries studies around the

Pacific Northwest, fluctuations in kokanee population size and fish

length are fairly common in unproductive bodies of fresh water such as

Crater Lake. Large increases in kokanee population size that occurred in

the lake during 1990-91 and 1999-2000 could therefore be expected.

Biologists studying Crater Lake believe that at low population size,

food is plentiful for the kokanee and a fewer number of fish eventually

reach larger size. These large and healthy adult fish reproduce

successfully leading to an increase in fish numbers. As the fish

population increases, the primary food of kokanee (microscopic animals

in the water column called zooplankton) decreases to the point that the

lake can no longer support such a high population of fish. The kokanee

population size then falls through time, allowing the zooplankton

population to recover so that the cycle starts over again. In water

bodies other than Crater Lake, the patterns in kokanee size and number

are subject to more variables such as fluctuations in water level (this

is especially pronounced in reservoirs), water temperature, fish

stocking density, the timing of stocking, and harvest pressure from

anglers.

Rainbow trout do not feed on zooplankton like kokanee do, but instead

rely mostly on aquatic insects near the lakeshore as well as those that

land on the lake surface. Large rainbow trout will also eat small

kokanee. The length of the largest rainbow trout caught in Crater Lake

over the last 15 years has varied similarly to that of kokanee, but

delayed by 1-2 years (compare the upper and lower graphs in Figure 1).

Large rainbow trout were prevalent in 1991 (see Table 1) and have been

increasing in number the last few years. Not surprisingly, the presence

of exceptionally large rainbow trout appears to be associated with the

presence of large numbers of small kokanee.

Research has shown the ecology of Crater Lake to be very dynamic and

the fish population is no exception. Recent studies suggest that the

quality of fishing in the lake for the foreseeable future will fluctuate

depending upon the year. The extremely large increase in kokanee numbers

during 1999 and 2000 will probably result in their population crashing

(probably due to over exploitation of their food resources) in the next

few years. This was already becoming apparent in the summer of 2000,

given the dramatic increase in kokanee numbers over the previous two

years.

With numerous small kokanee salmon present, the summer of 2001 could

turn out to be a great time to catch that big rainbow trout in Crater

Lake. Although the density of fish in Crater Lake will probably never be

high like other more productive lakes of the Pacific Northwest, some

days at Crater Lake still promise to be very good fishing. Other days

may not be so good, but if you are going to experience a bad day of

fishing I cannot think of a better place to go than beautiful Crater

Lake.

Note: Fishing access at Crater Lake is fairly limited because of the

steep and dangerous caldera walls encircling the lake. A quarter mile

section of shoreline is accessible at the base of the Cleetwood Cove

Trail for fishing. Anglers can reach Wizard Island in the tour boat

operated by the park concessioner, a service allowing passengers to

disembark and fish on a day use basis. Devices such as float tubes and

rafts are not allowed on the lake due to erratic winds, jagged rocks,

and steep shorelines.

Crater Lake National Park's Long-term Limnological Monitoring Program

assesses many chemical and physical aspects of Crater Lake's ecology.

Part of monitoring the fish population involves setting nets to collect

fish for analysis. Each fish collected in the nets is measured for

length, weight, sex, and maturity level. Scales are collected from each

fish to determine fish age. The stomach contents of the fish are

preserved for later analysis. The monitoring program also uses a

scientific-grade acoustic system (a fancy "fish finder") to accurately

estimate the population size in the lake and assess fish distribution

within the water column.

Table 1: Length (inches) of

largest fish caught in nets by biologists between 1986 and 2000.

| Kokanee |

Rainbow |

|

Largest fish caught |

Average length of

largest 5 fish caught |

Largest fish caught |

Average length of

largest 5 fish caught |

1986

1987

1988

1989

1990

1991

1992

1993

1994

1995

1996

1997

1998

1999

2000 |

10.5

13.5

15.6

16.1

11.2

10.8

11.0

9.4

8.8

10.3

16.3

14.7

14.2

15.2 |

9.4

12.3

14.5

12.3

10.9

10.5

9.5

8.5

8.5

10.2

13.9

14.1

13.4

13.9 |

17.8

18.9

18.9

17.8

23.1

17.3

21.4

16.7

16.8

13.5

19.1

17.5

18.7

19.9 |

16.7

16.8

17.8

17.0

20.9

15.7

16.2

16.0

14.6

11.0

16.0

15.0

16.8

16.7 |

Scott Girdner is a fisheries biologist with the National Park

Service who has studied Crater Lake since 1995.

|