|

HAWAII NATURE NOTES

THE PUBLICATION OF THE

NATURALIST DIVISION, HAWAII NATIONAL PARK

AND THE HAWAII NATURAL HISTORY ASSOCIATION

MAUNA LOA, FIERY COLOSSUS OF THE PACIFIC

DESCRIPTION. Mauna Loa is the world's largest active

volcano and probably the largest single mountain of any sort on earth.

It rises 13,680 feet above sea level, and approximately 30,000 feet

above its base at the ocean floor. Its volume is of the order of 10,000

cubic miles, as compared to 80 cubic miles for the big cone of Mount

Shasta in California. This huge bulk has been built almost entirely by

the accumulation of thousands of thin flows of lava, the individual

flows averaging only about 10 feet in thickness.

In form, Mauna Loa is a very broad flat dome, the

slopes of which nowhere are steeper than about 12°. Similar slopes

extend outward beneath the water all the way to the sea floor. This type

of volcano is known as a shield volcano. At the summit of Mauna

Loa is an oval depression 3 miles long, 1.5 miles wide, and as much as

600 feet deep (Plates 8 and 9). This depression, commonly called "the

crater" but more properly termed a caldera, was formed by insinking of

the summit of the mountain. Its name is Mokuaweoweo. At the

northern and southern ends Mokuaweoweo coalesces with smaller nearly

circular pits formed in a similar manner (see Figure 3). Southwest of

the caldera there are two more of these pit craters, named Lua

Hou (New Pit) and Lua Hohonu (Deep Pit).

TABLE 2

Eruptions of Mauna Loa1

(After Stearns and Macdonald, 1946)

|

Date of

commencement |

Approximate

duration

(days) |

Location of

principal

outflow |

Altitude of

main vent

(feet) |

Approximate repose

period since last

eruption (months) |

Area of

lava flow

(square miles) |

Approximate

volume of lava

(cubic yards) |

| Year | Month

and

day |

Summit

eruption | Flank

eruption |

|

| 1832 | June 20 | 21 | (?) |

Summit | 13,000(?) | -- |

-- | -- |

| 1843 | Jan. 9 | 5 | 90 |

N. flank | 9,800 | 126 |

20.2 | 250,000,000 |

| 1849 | May | 15 | -- |

Summit | 213,000 | 73 |

-- | -- |

| 1851 | Aug. 8 | 21 | (?) |

Summit | 13,300 | 26 |

6.9 | 90,000,000 |

| 1832 | Feb. 17 | 1 | 20 |

NE. rift | 8,400 | 6 |

11.0 | 140,000,000 |

| 1855 | Aug. 11 | -- | 450 |

do. | 10,500(?) | 41 |

312.2 | 150,000,000 |

| 1859 | Jan. 23 | <1 | 300 |

N. flank | 9,200 | 26 |

432.7 | 4600,000,000 |

| 1863 | Dec. 30 | 120 | -- |

Summit | 13,000 | 73 |

-- | -- |

| 1868 | Mar. 27 | 1 | 515 |

S. rift | 3,300 | 23 |

49.1 | 4190,000,000 |

| 1870 | Jan. 1(?) | 14 | -- |

Summit | 13,000 | 21 |

-- | -- |

| 1871 | Aug. 1(?) | 30 | -- |

do. | 13,000 | 18 |

-- | -- |

| 1872 | Aug. 10 | 660 | -- |

do. | 13,000 | 11 |

-- | -- |

| 1873 | Jan. 6 | 2(?) | -- |

do. | 13,000 | 3 |

-- | -- |

| 1873 | Apr. 20 | 547 | -- |

do. | 13,000 | 3 |

-- | -- |

| 1875 | Jan. 10 | 30 | -- |

do. | 13,000 | 2 |

-- | -- |

| 1825 | Aug. 11 | 7 | -- |

do. | 13,000 | 6 |

-- | -- |

| 1876 | Feb. 13 | Short | -- |

do. | 13,000 | 6 |

-- | -- |

| 1877 | Feb. 14 | 10 | 71 |

W. flank | -180± | 12 |

-- | -- |

| 1880 | May 1 | 6 | -- |

Summit | 13,000 | 38 |

-- | -- |

| 1880 | Nov. 1 | -- | 280 |

NE. rift | 10,400 | 6 |

24.0 | 300,000,000 |

| 1887 | Jan. 16 | -- | 10 |

SW. rift | 5,700 | 65 |

411.3 | 4300,000,000 |

| 1892 | Nov. 30 | 3 | -- |

Summit | 13,000 | 68 |

-- | -- |

| 1896 | Apr. 21 | 16 | -- |

do. | 13,000 | 41 |

-- | -- |

| 1899 | July 4 | 4 | 19 |

NE. rift | 10,700 | 38 |

16.2 | 200,000,000 |

| 1903 | Oct. 6 | 60 | -- |

Summit | 13,000 | 50 |

-- | -- |

| 1907 | Jan. 9 | <1 | 15 |

SW. rift | 6,200 | 37 |

8.1 | 100,000,000 |

| 1914 | Nov. 25 | 48 | -- |

Summit | 13,000 | 94 |

-- | -- |

| 1916 | May 19 | -- | 14 |

SW. rift | 7,400 | 16 |

6.6 | 80,000,000 |

| 1919 | Sept. 29 | Short | 42 |

do. | 7,700 | 40 |

49.2 | 4350,000,000 |

| 1926 | Apr. 10 | Short | 14 |

SW. rift | 7,600 | 77 |

813.4 | 4150,000,000 |

| 1933 | Dec. 2 | 17 | <1 |

Summit | 13,000 | 91 |

2.0 | 100,000,000 |

| 1935 | Nov. 21 | <1 | 42 |

NE. rift | 12,100 | 23 |

913.8 | 160,000,000 |

| 1940 | Apr. 7 | 133 | <1 |

Summit | 13,000 | 51 |

103.9 | 100,000,000 |

| 1942 | Apr. 26 | 2 | 13 |

NE. rift | 9,200 | 20 |

1110.6 | 100,000,000 |

| 1943 | Nov. 21 | 3 | -- |

Summit | 13,000 | 18 |

(?) | (?)13 |

| 1949 | Jan. 6 | 145 | 2 |

do. | 13,000 | 61 |

5.6 | 77,000,000 |

| 1950 | June 1 | <1 | 23 |

SW. rift | 8.000 | 12 |

1435.0 | 14600,000,000 |

|

| Total |

| 1,328 | 1,352 |

|

|

|

251.8+ | 4,037,000,000+ |

1The duration for most of the eruptions previous to 1899 is

only approximate. Heavy columns of fume at Mokuaweoweo, apparently

representing copious gas release accompanied by little or no lava

discharge, were observed in January 1870, December 1887, March 1924,

November 1941, and August 1944. They are not indicated in the

table.

2Upper end of the flow cannot be identified with

certainty.

3Area above sea level. The volume below sea level is unknown,

but estimates give the following orders of magnitude:

1850—300,000,000 cubic yards; 1868—100,000,000 cubic yards;

1887—200,000,000 cubic yards; 1915—200,000,000 cubic yards;

1926—1,500,000 cubic yards. These are included in the volumes given

in the table.

4All eruptions in the caldera are listed at 13,000 feet

altitude, although many of them were a little lower.

5Flank eruption started April 7.

6Activity in the summit caldera may have been essentially

continuous from August 1872 to February 1877, only the must violent

activity being visible from Hilo.

7Submarine eruption off Kealakekua, on the west coast of

Hawaii.

82.5 square miles of this is the area of the thin flow near

the summit. An unknown area lies below sea level.

9About 0.5 square mile of this is covered by the thin flank

flow above the main cone and 0.8 square mile is in Mokuaweoweo

Caldera.

102.8 square miles is in Mokuaweoweo caldera and 1.1 square

miles outside the caldera.

122.8 square miles of this is covered by the thin flank flow

near the summit, and 0.5 square mile is in the caldera.

13Amount of lava liberated probably small; eruption was largely

a liberation of gas.

14Preliminary determination.

|

From the caldera at the summit of the mountain there

extend outward two prominent zones of fracturing—rift zones.

The rift zones are marked at the surface by many open fissures and

cinder and spatter cones built during eruption by the

accumulation of spatter and fragments of lava thrown into the air as

fountains of liquid lava at the source of lava flows. Some of the gobs

of liquid lava solidify in the air, and pile up into loosely cemented

cinder cones upon striking the ground. Others that are still liquid when

they strike the ground stick together and form spatter cones. One rift

zone extends southwestward from Mokuaweoweo caldera, and the other

northeastward toward the city of Hilo. A much less definite rift zone

extends northward toward the Humuula Saddle, between Mauna Loa and Mauna

Kea. On a clear day the profile of the northeast rift zone of Mauna Loa

can be seen from the vicinity of Park Headquarters as a succession of

hills (cinder cones). The most prominent of these is Puu Ulaula (Red

Hill), at an altitude of 10,000-feet, which is 200 feet high on its

downhill side. A rest house, located in one side of this cone, provides

shelter for travelers enroute to and from the summit.

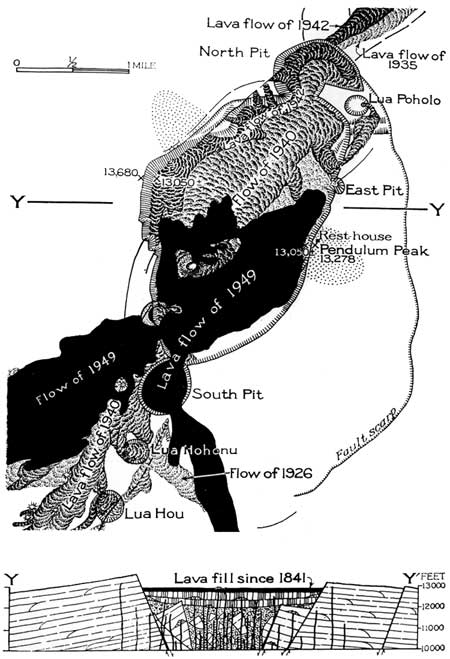

FIGURE 3. Map of cross-section of Makuaweoweo caldera after the 1949

eruption. Lua Poholo, East Pit, and Lua Hohonu are pit craters formed

since 1941. (Modified after Stearns and Macdonald, 1946, click on

image for an enlargement in a new window).

The fresh flows of aa lava extending downslope from

the rift zones appear black. The fresh pahoehoe flows may also appear

black, but when light is reflected from them they appear silvery gray

from a distance. Older lavas are dark gray, and still older ones

reddish-brown. Lava flows commonly divide, leaving within their

boundaries small "islands" of older land not covered by the new lava.

These islands are known in Hawaii as kipukas. From the vicinity

of Kilauea caldera the slopes of Mauna Loa show many variations in

color, depending on the age and surface characteristics of the different

flows. On the upper slopes of the mountain the newer black flows

surround kipukas of older gray or brown lava. On the lower slopes the

kipukas show as clumps of large trees, such as Kipuka Ki on the Mauna

Loa truck trail, or Kipuka Puaulu, in which Bird Park is situated.

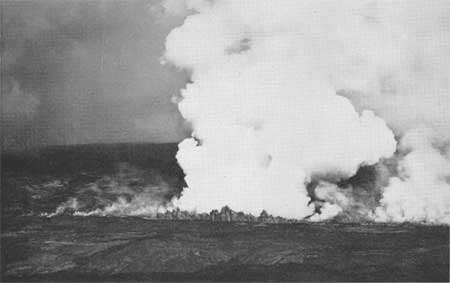

PLATE 3. A stream of liquid rock gliding smoothly into the sea is

recorded by a photographer who faced extreme heat to come within 100

feet of shore. Mauna Loa eruption, June 1950. (Hawaii Air National

Guard).

The growth of Mauna Loa was not entirely

uninterrupted. On its south eastern slope, a short distance west of

Hawaii National Park, is an area that received no new lava flows for

many thousands of years. There stream erosion carved big valleys into

the mountainside. The remains of these big valleys and the ridges that

separated them can still be clearly seen inland from Pahala and Punaluu,

although the valleys have been partly filled by new lava flows.

As the great cone of Mauna Loa approached its present

size it appears to have become somewhat unstable. There is a tendency

for the rocks to break along certain lines and for the blocks seaward

from the breaks to slide outward and downward toward the ocean. These

breaks are known as faults and the cliffs formed on the land

surface by the movements as fault scarps. A prominent series of

fault scarps, partly buried by later lava flows, lies just northwest of

the road from Park Headquarters to Pahala. The faults are still active,

and are the source of many earthquakes recorded on the seismographs of

the Hawaiian Volcano Observatory.

Extending inland from South Point, the Kahuku Pali is

a large fault scarp marking the edge of a downsunken area on the

southwest rift zone.

PLATE 4. 1950 lava flow of Mauna Loa approaching the sea. Many acres

of ohia forests and several buildings were destroyed by this eruption,

the first to strike the sea since 1926, when the village of Hoopuloa was

covered (Plate 10). (Hawaii Air National Guard).

ACTIVITY OF MAUNA LOA. Throughout the past century

Mauna Loa has been one of the most active volcanoes on earth. It has

erupted on an average of once every 3-1/2 years, and its eruptions

during that period have poured out a total of more than 3-1/2 billion

cubic yards of lava. The eruptions can be classified as summit

eruptions—those that occur in and near the summit caldera and

flank eruptions—those that occur lower on the flanks of the

mountain, generally on one of the rift zones. Probably all flank

eruptions begin with brief activity at the summit, followed after a few

hours of quiet by the outbreak on the flank.

A typical eruption of Mauna Loa begins with the

opening of a fissure or series of fissures, as much as 13 miles long

(Plate 5). From this fissure liquid lava squirts in a nearly continuous

line of low fountains, from a few feet to 50 feet high. This very

spectacular manifestation has been called the "curtain of

fire." From the fountains pour copious fast-moving floods of lava,

and along the fissure lava spatter builds up a nearly continuous wall, a

few feet high, known as a spatter rampart. The "curtain of fire"

is short-lived. generally lasting less than a day. The upper and lower

ends of the fissure then become inactive, and eruption is restricted to

a few hundred yards of the central part of the fissure. The lava

fountains increase in height, reaching as high as 800 feet (Plate 2),

and debris from the fountains accumulates around them to form a cinder

cone. Pumice and Pele's hair (natural spun glass) rain down on the

country to leeward of the vents. A great cloud of yellowish-brown gas

rises several thousand feet above the fountains. The principal flows of

lava issue during this stage, which may continue for weeks or even

months. Some of these flows reach the shore, and may be destructive

(Plate 10). Eventually the abundant gas liberation and high lava

fountains come to an end, and the final phase of the eruption consists

of a relatively quiet outpouring of lava. It usually is short, lasting

only a few hours, but it may continue for several weeks, as in the 1949

eruption.

PLATE 5. Lava fountains up to 300 feet high along Mauna Loa's

southwest rift, June 1950. Most of the 1950 lava was produced by these

fountains. (United States Air Force).

|