BUFFALO IN YELLOWSTONE PARK

by

Junior Naturalist Frank Oberhansley

Aside from the fact that buffaloes (Bison bison bison) were at least

moderately numerous in the region embraced by Yellowstone when this

became our first national park in 1872, we know little of the early

history of those animals in this region. This is not strange when we

remember that there were still millions of buffaloes roaming at large in

their native haunts. The supply as yet seemed inexhaustible. The early

explorers and visitors were attracted here by the expressions of nature

in the hot springs, geysers, and other natural wonders. It was natural

that only their impressions and interpretation of the unique were

written. Upon verification by the Geological Survey that such geologic

phenomena really existed here, this area was set aside as a national

park in order that it might be preserved in its natural state by the

government for the "benefit and enjoyment" of all the people, forever.

The thought of making Yellowstone a game preserve was incidental to the

main issue.

From the time of discovery until 1886 hunting was deemed essential to

the success of any expedition to this remote area. Market hunters were

well established in the northern section of the park as early as 1873.

The first superintendent, N. P. Langford, recommended that hunting be

restricted to the needs of residents of the park and its visitors, but

for want of any salary he was prevented from residing here and seriously

checking these activities during his five year term.

In the pioneering venture of creating a national park, Congress

overlooked the item of providing money for administration and

protection; consequently for a period of five years no government funds

were available and hunters had things pretty much their own way in

Yellowstone. When money was first appropriated in 1877, the beginning of

the end was in sight for the buffalo. At this time Superintendent Norris

stated that thousands of hides had been taken out and that it was the

practice of the hunters to poison the carcasses which were left as bait

for wolf and wolverine. He predicted correctly that within the decade

buffaloes would become extinct or exceedingly rare outside of this

government area. It was estimated that there were three or four hundred

head of the "curly, nearly black bison" (1) left in the park. They were

described by Norris as being "smaller, of lighter color and with horns

smaller and less spreading than those of the bison that formerly

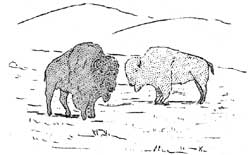

inhabited Colorado." (1). Figgins described the mountain buffalo (Bison

bison haningtoni) as being much lighter in color, "notably in the head,

neck, and forelimbs" (2) than the plains buffalo (Bison bison bison).

Grinnell stated that the "Mountain Buffalo" (3) was abundant in

Yellowstone Park in 1875 and called attention to the terrible

destruction of these animals for their hides alone. These mountain

buffalo were considered to be more fleet and intelligent than the plains

animals. Their hides were also more valuable as they were darker, finer,

and more curly.

In 1880 Mr. Norris estimated 600 buffaloes for the park, 300 of which

were only summer residents and having their winter range to the west in

Idaho. The other animals ranged in the eastern and northeastern section

of the park. During the year a game keeper was employed to assist Mr.

Norris in protecting the buffalo and other animals. By Superintendent's

Order the buffalo was protected in 1879. Montana also provided a

protection law that year.

From 1882 to 1885 we can learn nothing of the status of the buffalo

in Yellowstone. Reports of slaughter moved Congress to replace civilian

employees with Cavalry troops of the army, the commanding officers

acting as superintendents for a period of 30 years when the National

Park Service of today was created. Protective work was ineffectual as no

suitable court or laws were provided for offenders. The work of the

soldiers was augmented by civilian scouts acting in the nature of game

wardens.

In 1886 all hunting in Yellowstone was prohibited by law but no court

was provided to try cases, the only punishment being arrest and

expulsion from the park and confiscation of outfit. This proved to be an

excellent gamble for poachers with cheap outfits when a good head was

worth $400.

Captain Harris estimated 100 buffalo in 1837. The following year he

dispatched a patrol on snowshoes to the winter range with the idea of

finding out how many buffaloes were left. This patrol encountered only

three head. A later patrol in March succeeded in finding signs of about

100 animals that had wintered in the vicinity of Mary Mountain. During

the following spring several buffaloes were seen along the Firehole

River whose range was thought to extend across the Madison Plateau to

the southwest corner. Thee total estimate was then raised to 200

head.

Captain Boutelle became superintendent in 1890. He observed a

scarcity of calves and thought cougars and lions were preying upon them.

Sensing the perilous plight of the buffalo, appeals were sent to the

governors of the states of Wyoming and Idaho for protection of animals

that might drift from the park into these states. Wyoming enacted a good

protection law the same year but Idaho ignored the request and continued

to harbor the most notorious set of poachers known, in the vicinity of

Henrys Lake near the western border of the park.

From 1891 to 1897 Captain George S. Anderson served as military

superintendent. He noted the activities of the merciless freebooters of

Henrys Lake and learned of several heads being marketed in surrounding

towns at from four to five hundred dollars. Several arrests were made in

this vicinity, but no convictions were secured. During the winter of

1894 a notorious poacher from Cooke, Montana was arrested in Hayden

Valley with six hides in possession. Scout Burgess and Sergeant Troike

apprehended him in the act of stalking a small band of buffaloes. His

final conviction was the first under the new protection law of 1894. A

court was established that year in the park with John W. Meldrum as

first United States Commissioner to try cases and assess penalties.

From 1891 to 1894 Captain Anderson estimated there were 400 buffalo

left in the park when suddenly the estimate dropped to 200. Seventy five

were counted on the west side and reports of many more in 1891.

Evidently, the Idaho poachers were quite successful, for in the year

1896 it was estimated there were only 25 or 30 head left in the entire

park, and doubts were expressed that they could be saved. Attempts were

made to capture a few of them by providing hay in a corral in Hayden

Valley but with no success. Hay was cut and stacked in Pelican Valley in

hopes the buffalo would find it. Winter snows covered it so deeply,

however, that even the scouts could not locate it. Special money was

made available by the War Department in a final effort to save the

buffalo from complete extermination. Experienced hunters and other

mountain men were employed to assist the scouts and soldiers but their

efforts were of no avail as the damage was nearly complete. Only the

carcasses were left as evidence of the fact that buffalo had inhabited

the southwestern and western sections of the park. Poachers had reduced

the herd to an estimated 22 head by 1902.

With buffalo so near to extinction, it was decided to import an

entirely new herd, and gradually release some of these animals, thus

introducing new blood into the wild herd. Accordingly, 18 cows were

secured from the Pablo-Allard herd in Montana and delivered by Howard

Eaton. At the same time, 3 bulls were secured from the Goodnight herd in

Texas by C. J. (Buffalo) Jones who was employed as game warden in charge

of buffalo. These animals were kept in a large enclosed pasture one mile

south of Mammoth until 1907 at which time the herd had grown in number

to 61 head. Three calves were captured from the wild herd and raised by

domestic cows. The pasture proved insufficient to meet the needs of the

ever-increasing herd so a new site was selected on the present location

of the Buffalo Ranch in Lamar Valley at the mouth of Rose Creek. Here a

portion of the valley bottom was fenced off to protect the wild grasses

which were harvested in the fall for winter feed. The north slopes of

the valley including about 600 acres were fenced for summer pasture

land. Comfortable living quarters were provided for the buffalo keeper

at the present site.

As early as 1908 it was felt that there were too many bulls in the

herd. They were constantly fighting and endangering the lives of the

calves. In order to relieve the condition, fourteen bulls were separated

from the herd and driven to Mammoth as the first show herd. Late in the

fall they were returned to the main herd. The practice of maintaining a

show herd at Mammoth continued until 1935 when a more suitable location

on Antelope Creek was selected. Hundreds of thousands of visitors have

thus been benefitted; as buffalo could rarely be seen by them on the

inaccessible summer range.

The Lamar herd had grown until in 1910 it numbered 121 head, 61 males

and 60 females. The original summer pasture proved inadequate so the

herd was turned out each morning to graze. At first they were herded

carefully and driven into the enclosure every two hours in order to

accustom them to being handled. Later they were herded during the

daytime and returned to the pasture at night. This practice of day

herding was continued until 1915 when it was thought to be unnecessary.

Since that time, the herd has gradually reverted to a wild state until

today the Yellowstone buffalo are perhaps fully as wild as the plains

buffalo of old.

In December 1911, just after the buffaloes were taken from the range

where they had been day herded during the summer, 22 of the younger

animals (15% of the herd) died. Blackleg was at first suspected and fear

of losing the entire herd prompted quick action. The disease was found

to be Hemorrhagic septicemia, a blood disease for which the entire herd

was vaccinated in June of that year. There was a recurrence of the

disease in 1919 when 26 of the buffaloes died in spite of previous

vaccinations in 1917 and 1918. A third attack of the disease threatened

the herd of 578 in 1922. Fifty two of the animals died before serum

could be secured from the Bureau of Animal Industry. The new serum of

1922 proved to be 100% effective in immunizing buffalo against the

disease and from that time until the present a fresh supply has been

available at the Buffalo Ranch ready for instant use.

In the meantime, the original wild animals were not molested by

poachers. They ranged widely over the park country east of Yellowstone

Lake and River, so wild that they were seldom seen even by the scouts or

later by the rangers, except when special patrols were made. Seventy two

head were counted in 1916 and 67 in 1917. Since that time there has been

a gradual overlapping of the ranges of the two herds until at the

present time they have thoroughly intermingled. There is still a

tendency for the animals to winter in distinct herds. The main herd at

the Buffalo Ranch is fed hay during the hardest part of the winter.

Another group varying in number to as many as 300 animals, winters in

the valleys east of Yellowstone Lake without artificial feed. During the

past two two small herds, numbering 36 and 35 were separated from the

main herd and turned loose in Hayden Valley and the Lower Geyser Basin,

respectively, in order to reduce the main herd and at the same time

establish the buffalo on his former range. These animals seem to be

doing well in their new locations. Twenty eight were counted in Hayden

Valley in September while thirty were seen in January in the Lower

Geyser Basin.

The early problem of surplus bulls in the herd was partially met by

establishing a show herd at Mammoth, through live shipments, to public

parks and zoos and to private estates for exhibition purposes. As early

as 1904, attempts were made to rejuvenate the wild herd with new blood

by liberating one of the new bulls in Pelican Valley. This venure was a

failure as the bull was found dead near Thumb station the following

spring. Subsequent attempts were made to reduce the number of bulls by

driving them from the Buffalo Ranch anticipating that they would join

the wild herd, but fortunately for the wild herd they always returned to

the Ranch. Finally, permission to slaughter and sell the meat of surplus

buffaloes was granted by Congress to park officials so in the event that

live shipments do not balance the herd against feed and available range,

there is always a way provided for a sound management program. It has

been established that facilities in Yellowstone are adequate for

approximately 1000 buffaloes and for the best interests of the park as a

whole this figure has been adhered to rather closely during the past few

years. In 1918, 66% (44 head) of the male calves of 1917 and 1918 were

castrated during the vaccination of the herd for Hemorrhagic septicemia.

These steers and others following were slaughtered at the Buffalo Ranch,

the meat in later years having been donated to relief organizations and

Indian agencies in the states bordering the park. Total live shipments

to zoos and reservations from the park number 1351 to date.

From the small herd of eighteen cows and three bulls established in

Yellowstone in 1902 plus the remnant of the original herd which was

assimilated in later years, the present herds total approximately 1000

head, while a total of 2182 surplus animals have been disposed of. Many

fine herds have been establish throughout the country from the

Yellowstone surplus.

Under the sound agement program of late years, the future of the

buffalo in the park has never been brighter.

References for the above article:

1. Superintendents' Annual Reports

2. Figgins, J. A., Bison of the Western Area of the Mississippi

Basin, Vol. XII, p. 30.

3. Grinnell, George Bird and Ludlow, Captain - A Reconnaissance from

Carroll, Montana to Yellowstone National Park in 1875.