HORNS AND ANTLERS

by Junior Naturalist Frank Oberhansley

Elk antlers stimulate many questions on the part of visitors to

Yellowstone Park. Some one is forever wanting to know where he can

secure some "elk horns" or how many dead elk were necessary to provide

the "makings" for the antler house at Mammoth. After close scrutiny of

this structure, one visitor inquired as to the type of roots used in its

construction.

For the reader who is not familiar with the major facts relating to

horns and antlers the following is offered.

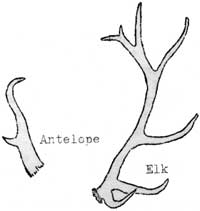

Only one animal in the world sheds his horns naturally and this is

the American antelope (Catelocarpidae americana). This statement will

immediately bring forth the challenge from many. "What about the deer,

elk, and moose?" The answer lies in the fact that there is a distinct

difference between horns and antlers. Horns are outgrowths of the skim

similar to nails, claws, and hair, while antlers are true bone growths,

exposed parts of the skeleton.

In the case of the elk (Cervus canadensis), the antlers are shed from

late winter to early spring. A few spike bulls were observed carrying

the antlers this year until late in May. Just what is the direct cause

of the actual shedding is unknown. Perhaps the new growth has something

to do with it, or it may be that the bony tissue attaching the antler to

the skull becomes dead and incapable of further supporting this great

weight firmly. At any rate, there is some physiological change which

causes the antler to drop at the correct season.

Almost immediately after the old antlers are shed new ones begin to

replace them. From the beginning those new antlers are very blunt.

Covered with a velvet-like tissue and richly supplied with blood vessels

and nerves, they are comparatively soft and highly sensitive. The

profuse blood supply enables the antlers to grow at an alarming rate

until by September 1 they are fully mature. During the growing state the

antlers are said to be "in the velvet" and when the growth is completed

the velvet is commonly shed by rubbing the head against a small tree and

exposing the true bony antler. Some maintain this rubbing is for the

purpose of sharpening the antlers preparatory to the fighting incident

to the mating season. Personally, I believe it to be a natural means of

relieving an irritation incident to a stricture of the nerves and blood

vessels at the base of the antler where a ring of bone solidifies and

chokes off any further supply of raw materials.

As soon as the velvet is shed the bulls are ready to fight for the

possession of a harem. Although the antlers are fully formed, they are

still green and occasionally in the initial clashes between two bulls,

the antlers may be sprung slightly so that they may become locked

tightly and death comes to both combatants.

It seems to be Nature's plan that during, the time the cows are with

calf and while the calves are using a large supply of milk, the bulls

are undergoing changes in the generative organs simultaneous with the

growth of antlers during which time the bulls and cows tend to range

separately in groups of varying numbers. The shedding of the velvet is

coincident with the mating instinct which brings the two sexes together

again in the fall.

As the season progresses the antlers become increasingly dead tissue

until the final shedding when the process is repeated.

The antelope sheds his horns in the late fall. In this case the outer

sheath only is shed leaving a bony core. At this time he may be said to

have antlers similar in structure at least to those of elk, since they

are true bone. Coarse black hair soon covers this bony core and

eventually these become cemented together with a chitinous like material

to form the true horny sheath. As stated earlier, no other animal sheds

its horns.