The following is the third article of the series on Yellowstone Elk or

Wapiti (Cervus canadensis canadensis) -- The Editor.

YELLOWSTONE ELK - A RESERVOIR FOR RESTOCKING PURPOSES

by

District Ranger Leon Evans

All sections of the United States, with the exception of the desert

areas, were originally well stocked with many species of big game

animals but the expansion of agricultural operations drastically reduced

the range of these larger species while uncontrolled hunting caused near

extinction of such animals as elk, buffalo, deer and others. The birds

and small game were able to survive in limited numbers as their forage

requirements were low and they were able to evade the hunters in the

limited remaining cover.

After conservationists had secured the enactment of legislation

designed to protect the game resources, it became desirable to attempt

to restock some ranges which were not suitable for agriculture or other

development. Yellowstone National Park was called upon to supply elk for

restocking and was in a position to respond because the winter range of

the Northern herd made them accessible during the winter months which is

the best time to successfully trap live elk.

Although some elk had been shipped to zoological parks previous to

that time, the year 1912 marked the beginning of large scale shipments

for restocking purposes. During that season the State of Washington

secured 106 while 30 were transplanted to Glacier National Park. Since

the inauguration of the policy of disposing of surplus elk by live

shipments, over 5,000 have been successfully transported to other areas

where they have served as the nucleus of new herds or have added new

blood to other bands whose numbers had been seriously depleted.

There were originally one predominant species and three sub-species

of elk found in North America, but only one "Cervus canadensis

canadensis" was well distributed and this group included those in

Yellowstone National Park. It is the policy of the National Park Service

to restrict shipments for restocking to sections of the primitive range

of this species described by Hornaday as follows: "The former range of

the elk covered absolutely the garden ground of our continent, omitting

the arid region. Its boundary extended from central Massachusetts to

northern Georgia, southern Illinois, northern Texas -- the whole Rocky

Mountain region up to the Peace River and Manitoba." The there other

sub-species were found in California, some sections of Arizona and the

Pacific Northwest. The vast wildlife reservoir of Yellowstone has sent

elk to nearly every corner of their former range where there still

remained enough unoccupied land and available forage to support them. In

addition, a large number of zoos, zoological gardens, and parks have

been supplied with elk for display purposes.

The job of securing wild animals such as elk is surrounded by

difficulties. Attempts to handle then in the same manner as domestic

range stock have been uniformly unsuccessful as they cannot be driven or

herded by men on horseback. The one factor which makes their capture

possible is the winter snow which drives them to the lower elevations

and puts a drastic limit on the available forage. Only during time

winter months when they feel the pangs of hunger can they be lured into

traps by the hay which is scattered both inside and outside the

corrals.

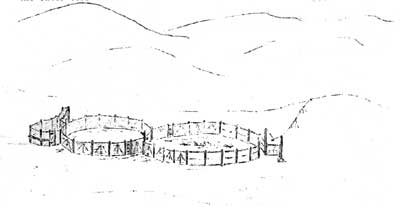

These corrals used to trap elk are usually circular and a complete

trap consists of two large corrals, one or more smaller pens and a

loading chute all of which are connected by gates. The first large

corral is about ten feet in height and is constructed of heavy woven

wire stock fencing on heavy poles for the front section as the animals

will not readily enter an enclosure unless they can see out. The half of

the fence on the side which connects with the second corral is boarded

to the top. The elk enter the trap by a large gate in the front of the

first corral. This gate is designed so that it will swing shut when

released. When trapping operations are in progress this gate is fastened

in the open position by a latch which is in turn attached to a long

trigger line that may be from 100 yards to one-quarter of a mile in

length and is held up by tripod type supports. This long trigger line

enables the ranger to quietly approach within view of the trap and still

remain a sufficient distance away to avoid disturbing the elk which may

enter the outer corral to feed on the hay.

The actual trapping is usually done at night so the rangers engaged

in the work have to make regular trips to their vantage points from the

time darkness falls until daybreak. The actual time that elk enter the

trap is dependent, to a large extent, upon the brightness of the night

and upon weather conditions. When the moon is full, elk feed almost

entirely at night and retire to protected timber areas during the day.

Binoculars, with a high degree of light-gathering power are used to

enable the operator to view the trap in the darkness, but on many stormy

or very dark nights he is forced to pull the trigger and trust to

luck.

After the gate swings shut the captured animals are immediately

herded into the second corral which is boarded the full height for its

entire circumference. This leaves the approach section free for further

operation and the captured animals are held in this second corral where

they are fed and watered until being transported to their new

ranges.

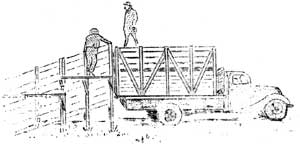

Long experience has demonstrated that shipments should be made as

soon after the animals are captured as possible so they are seldom held

in the traps for more than a few days. Live shipments to areas within

200 to 400 miles are now made by trucks equipped with stock racks which

may provide for from 10 to 25 elk. Care is exercised to prevent undue

crowding during transit. When the trucks arrive, they are backed up to a

loading chute very similar to those used for leading cattle or other

livestock. Shipments to more distant points are made by rail, either

express or freight, the animals being first transported to the rail head

by trucks. The elk are fed and watered by the company when sent by

express, while special attendants are provided when freight shipments

are made.

Individual shipments are made in special crates that are fitted with

doors for feeding and watering. It is possible for the animal to lie

down in one of these crates and for unusually long shipments the sides

are padded with as much care as a manufacturer of furniture prepares a

deluxe chair for his best customer. Often the elk shipped in this manner

become world travelers, such as the pair recently shipped to the

Zoological Gardens in Buenos Aires, Argentina.

The loading operations are attended by much strenuous work and

considerable excitement. A few head of elk are permitted to enter the

small pens where they are carefully examined and undesirable animals are

released. Those selected for shipment are then crowded, one or two at a

time, into the loading chute where the sex and age are determined and a

metal tag, bearing a serial number is inserted in the ear of each animal

for future identification. A careful record is thus made of each animal

and hunters who secure a tagged elk are requested to return the band to

the address thereon, and in this way much valuable data is compiled on

migrations, age, and other pertinent facts. The antlers of bull elk are

cut off so that the other animals will not be injured in shipment. This

is not harmful to the bulls and the remaining stubs will be shed in the

spring and be replaced with a new pair of normal antlers by the

following fall.

Free on the range, the elk may be a timid and shy creature of the

wild, in the close quarters of a pen some become paralyzed with fear and

excitement, while others will exhibit all the stubborn characteristics

of an army mule combined with the pugnacity of a wildcat. A cow "on the

prod" will valiantly stand her ground, gnashing her teeth and barking

defiance at her tormentors. When a small side door is opened by a ranger

attempting to urge her into the chute, she will charge with all the fury

of an enraged grizzly. Failure to quickly dodge out of the small door in

time to avoid the onrush is apt to result in serious injury for the

flying hooves are formidable weapons of offense. Experience has shown

that elk may best be handled by maintaining peace and quietness at the

loading chute. Noise and turmoil cause elk to become excited and hard to

handle, while these wild creatures easily comprehend careful management

and a calm atmosphere at the corral.

Once the animals are loaded, the drivers make all possible haste in

getting them to their destination so that losses in transit are kept to

a minimum. No stops, other than those for gasoline and drivers' meals

are made so that although it is a tough life for the drivers the elk are

kept in their restricted space only as long as absolutely necessary.

Before shipments to any locality are authorized, the United States

Forest Service, the State Fish and Game Department and all other

agencies directly concerned must approve the restocking program. This is

essential, as proper protection and management must follow if the elk

are to survive and increase. The success of the program is well

illustrated by the following item which appeared in the "Daily News", a

publication of the United States Forest Service, Region IV, Ogden,

Utah:

"THIRTY-TWO ELK MULTIPLY TO 500 HEAD IN 20 YEARS"

"Wise management increases game in national forests. A recent count

by the Forest Service shows 126,000 elk now in protected national forest

areas - enough to allow a short hunting season.

"How rapidly elk multiply is shown by the herd in the Helena National

Forest in Montana. An importation of 32 elk in 1917 has grown into a

herd of 500 head. In this isolated region along the continental divide,

elk summer in the rough highlands and winter on the lower levels, where

they feed on pasture land and abandoned dryland wheat fields.

"Importing the 32 elk from an overstocked game area cost only $250.

Seven were killed before Montana passed a protecting game law in 1918.

The herd grew to 250 by 1927.

"Twenty-one bull elk were taken by hunters in 1932, when one day of

hunting was allowed. By 1936 close to 500 elk were counted and another

open hunting day yielded 25 bull elk to sportsmen.

"During the past winter (1937-1938) State and Federal officials

received complaints from farmers that the elk were eating crops in the

neighborhood of the 900,000-acre national forest. A 3-week open season

was allowed. Seven hundred hunters registered. Seventy-five elk were

killed the first day. Fifty-five more were killed before the hunting

season closed.

"Forest Service officials say the several hundred remaining elk are

enough to furnish a big game supply for future hunting seasons."

-- U. S. D. A. Clip Sheet

In addition to serving as a recreational area for approximately half

a million visitors who come each season to view the scenic Yellowstone

National Park, this huge area of 3,472 square miles serves as a source

of big game, for each fall many animals drift a cross its boundaries and

furnish excellent hunting in the surrounding states. This great

sanctuary has also supplied zoos, National Forests, National Parks, and

State Game ranges with buffalo, elk, and bears for exhibition and

restocking purposes. While hunting within the park is strictly

prohibited, it has directly provided sportsmen with hunting due to

natural migration and the shipment of game animals to other ranges.