|

THE BIOGRAPHY OF A BEETLE

By Fred H. Arnold,

Regional Forester.

In common with most of the destructive tree insect

pests in the United States the Japanese beetle is of exotic orgin. Its

native home is Japan, hence the name by which it is commonly known.

Entomologists speak of this "bug" as Popillia Japonica. First

discovered in this country near Riverton, N. J., in 1916, it since has

thrived and spread throughout southern and central New Jersey, eastern

Pennsylvania, and northern Delaware. Beyond this area the beetles have

been found from New England to South Carolina and as far west as

Missouri. Despite strict quarantine regulations enforced by the U. S.

Department of Agriculture and other efforts to check it, the beetle

appears to be increasing gradually in numbers and widening its

geographical distribution.

There are four stages in the life history of this

destructive pest, namely; the adult (beetle), egg, larva (grub), and

pupa. Anyone who has seen the adult beetle will not soon forget its

striking appearance. It has a lustrous metallic green color with a

bronze sheen on the wing covers. Broadly oval in shape it is slightly

less than one-half inch long and one-fourth inch wide. The eggs are

between one-sixteenth and one-eighth inch long, elliptical to nearly

spherical, and of a creamy white color. The typically curled larva

varies in length up to an inch, with a white body that is bluish within,

and with a light brown head. About the size of the adult and resembling

it somewhat, the fully developed pupa is tan in color and elliptically

shaped.

Depending upon the advance of the spring season and

varying with latitude and elevation, the adult beetles emerge from the

soil during June and July. Immediately they begin to feed upon plant

leaves and flowers, having voracious appetites. They habitually mass

themselves in dense clusters on certain individual plants which are thus

heavily fed upon, while seemingly ignoring other nearby plants of the

same kind. As many as 296 beetles have been found massed upon a single

apple. The adults are short-lived, averaging one month to a month and a

half of life as herbivorous gourmands. They feed and fly about most

vigorously on warm, sunny days and similarly during the warmer part of

the day, between 10 A.M. and 3 P.M. Early in the morning and late in the

afternoon they feed on the lower plants, and during the middle of the

day when they are most active they are likely to be found seeking food

on the higher trees. The beetles are relatively in active on cloudy or

cool days. By late August most of the adults have dies, their bodies

lying on the ground beneath the badly mutilated host plants. Late

individuals occasionally may be found flying about until October since

all do not leave the soil at the same time.

Egg-laying begins soon after emergence, the females

burrowing a few inches into the soil and depositing one to four eggs at

a time. Another group of eggs may be laid after a day or two of feeding,

and this program is repeated until mid-August by which time each female

has deposited between 40 and 60 eggs. Both male and female beetles

continue to feed ravenously from the time of their emergence until

death.

The eggs require only about two weeks to hatch after

they are laid. The resultant grubs feed upon the finer roots in the

soil, particularly those of grasses, legumes, and of certain flowers and

garden vegetables. Extensive patches of lawns may be killed as a result

of this injury. During this feeding period the larvae work within the

upper three inches of the soil, but with the approach of winter they

burrow deeper and spend the winter in an inactive state at depths of

from four to eight inches below the surface. With the rising of soil

temperatures in the spring the larvae move upward and again feed on

roots between April and June. During May or June they are transformed to

the pupal stage which is a dormant condition lasting from one to three

weeks depending upon the climate and other local conditions. Pupae then

are transformed into adult beetles which in turn emerge from the soil

and the life cycle is thus complete.

The Japanese beetle is known to feed upon a great

variety of plants. Nearly 300 different species of non-evergreen trees,

shrubs, and flowers are eaten by the adult beetles with varying degrees

of preference. Certain species, such as apple peach, plum, cherry,

grape, rose, elm, horse chestnut, sassafras, willow, basswood,

raspberry, blueberry, dahlia, hibiscus, hollyhock, and zinnia, are

highly susceptible to attack by the insect and are heavily damaged by

it. Other plants, however, are relatively resistant to it and are only

seldom attacked. Some of these more or less immune plants are

evergreens, including rhododendron and azalea, ash, beech, most of the

oaks and maples, honeysuckle, redbud hydrangea, lilac, privet,

forsythia, peony, petunia, tulip, gladiolus, and phlox. The beetles

usually feed upon the tender tissue between the veins of the leaves,

thereby skeletonizing patches of or the entire leaves, and leaving only

the ribs and veins. Blossoms and fruits also are consumed. Flowers,

shrubs, and, in cases of severe in festations, even large shade trees,

may be defoliated completely.

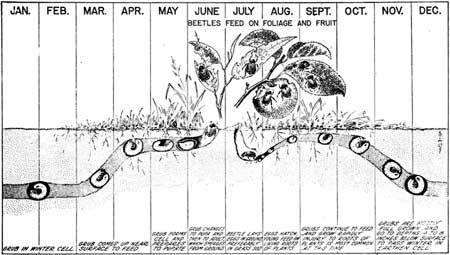

SKETCH SHOWING LIFE HISTORY AND FEEDING HABITS OF JAPANESE BEETLE

SKETCH SHOWING LIFE HISTORY AND FEEDING HABITS OF JAPANESE BEETLE

(Reproduced from U.S.D.A. Circular No. 332)

(click on image for an enlargement in a new window)

Several outbreaks of this pest now occur in National

Park and Monument areas in Region One. At George Washington Birthplace

National Monument, in Westmoreland County, Va., a heavy infestation has

become established National Capital Parks, Washington, D. C., have a

Japanese beetle problem. A vigorous attack was recently reported at Fort

McHenry National Park, Baltimore, Md. Morristown National Historical

Perk Morristown, N. J., is troubled with the pest, and the famous Statue

of Liberty National Monument on Bedloe's Island, N. Y., also is host to

the insect.

The Japanese beetle is now so widely and heavily

distributed that its complete eradication is beyond practical means of

accomplishment. Its spread may be checked and its numbers and the amount

of damage reduced, however, by energetic and intelligent application of

various control measures that are known at present. These measures are

briefly as follows:

1. Spraying the soil in infested areas with lead

arsenate to poison the grubs.

2. Spraying infested plants with a poison, such as

pyrethrum, which kills by contact with the insect.

3. Strict enforcement of state and Federal quarantine

regulations restricting the transportation of soil, potted plants,

nursery stock, and other plant material.

4. Trapping with specially designed beetle traps.

5. Hand collection before and during egg laying.

6. Introduction and encouragement of natural control

agencies, such as parasitic insect enemies, birds, and other animal

predators of both adults and larvae.

7. Planting species which are not susceptible to

attack.

8. In the yard and garden, valued plants may be

protected against damage by spraying them with a repellant such as

aluminum sulfate. Lead arsenate is a stomach poison as well as a

repellant but it destroys flowers, young leaves and other tender plant

tissues.

From all outward indications this foreign beetle is

here to stay; its ravages will vary in intensity from year to year

depending up on climatic and other factors; it will exact an annual toll

in destruction of vegetation; and our hope should be, through the

application and encouragement of natural and artificial controls,to keep

down the peak epidemics, thereby leveling off the curve of annual

losses.

REFERENCES

United States Department of Agriculture Circular No.

332, December, 1934, General Information about the Japanese Beetle in

the United States, by C. H. Hadley and I. M. Hawley.

United States Department of Agriculture Circular No.

237, Revised July, 1936, Control of the Japanese Beetle on Fruit and

Shade Trees, by W. E. Fleming and F. W. Metzger.

United States Department of Agriculture Circular No.

401, September 1936, Control of the Japanese Beetle and its Grub in Home

Yards, by W. E. Fleming and F. W. Metzger.

|