|

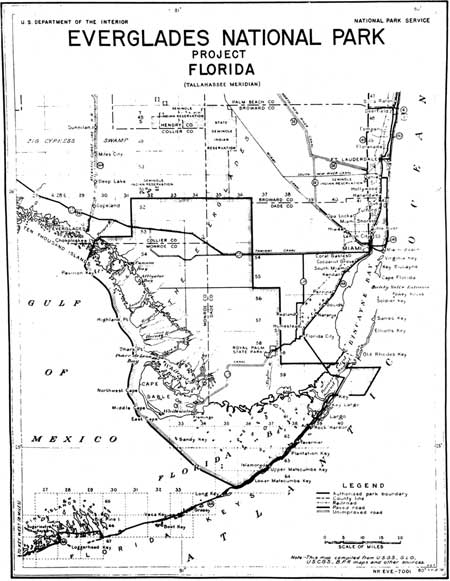

(click on image for an enlargement in a new window)

DIVERSITY IN THE EVERGLADES

By Daniel B. Beard,

Assistant Wildlife Technician

After eight years of investigations, counter

investigations, and super investigations, the boundaries of the proposed

Everglades National Park in Southern Florida remain substantially the

same as they were originally set up. It may appear odd that no radical

boundary changes have been made in such flat country-land that is only a

few feet above sea level, possibly eight or ten feet at its dizziest

height. Maybe, if I can describe the terrain along the three hundred or

so miles of boundaries it will be possible to get an inkling of the

diversified nature of the ground, level as it is in the proposed

park

The place where the boundary cuts across the Tamiami

Trail about 30 miles west of Miami would make a good starting point.

This is State property. The country is a flat expanse of sawgrass

prairie, dotted. by occasional hammocks which give the appearance of

islands. Under natural conditions, the grasses and sedges of the prairie

grow almost shoulder-high, and the ground is soggy marl covered by a

skim of organic soil. The little hammocks have more fertile soil than

the surrounding prairies and support a luxuriant growth of cocoplum,

butttonwood and other trees, shrubs, and airplants Seminole Indians

build their thatched villages on 'glade's hammocks and sometimes plant

pumpkins bananas, sugar cane and other essential crops. There the women

can be high, by a foot or so, and reasonably dry while the men hunt

alligators, deer, and otters or go spearing fish in the winding

waterways from their dugout canoes

About 25 miles south of the starting point the park

boundary skirts Royal Palm State Park to include that area. Thanks to a

wet slough to the east of Paradise Key in the State Park the vegetation

growing on the Key has been relatively free from the ravages of fire On

the pitted oolitic limestone of Paradise Key, a tropical jungle has

developed with the tousled heads of royal palms protruding high above

the forest canopy. Here are found plants that could keep the most

ambitious botanis busy for years-gumbo limbo, blolly, wild coffee.

bustic, stopper mastic poisonwood, paradise tree, moon vine, strangler

fig quantities of rare epiphitic orchids, and many others. Nearby are

the piney woods of the Everglades Keys.

As we move southward, the grassy prairies thin out

and little, round hammocks become more numerous in a land of flat, gray

marl. Small red mangrove trees with arching roots indicate the proximity

of salt water. We are approaching an almost unexplored wilderness of

tidal lakes and estuaries where the American Crocodile is making its

last stand. The park boundary makes an abrupt swing to the east near the

southern coast of the mainland, crosses over a shallow bay to the

northern end of Key Largo and, strangely enough, goes right out into the

ocean for a few miles. The reason for this can be quickly ascertained by

peering into the water through a glass-bottomed bucket. There is a shelf

extending out from Key Largo for several miles which is the remnant of

an old, submerged coral reef. At the outer edge of the shelf, a new,

barrier coral reef is forming. Through the bucket, one can see waving

gorgonias, lumpy coral heads, sponges, and the tropical fishes of the

Atlantic marine gardens.

The boundary cuts back across Key Largo again after

following the edge of the coral reef for a few miles, thus including a

section of that key. That will bring into the Everglades Park an example

of West Indian jungle vegetation growing on the "core" of Key Largo and

flanked on both sides by impenetrable mangrove swamps.

From Key Largo, the boundary follows southward along

the inner edge of the Upper Florida Keys as far as the end of Lower

Matecumbe. Then it swings off to the northwest across the water to a

point three miles from Cape Sable, the southernmost spot on the United

States mainland. This means that Florida Bay is included in the park.

The Bay appears on the map to be just an expanse of water dotted with

little islands. It is a vast expanse of milky, blue water and mangrove

keys, but the water is only a few feet deep. Smart boatmen carry shovels

with them and get out to dig a channel every so often. The marl from the

mainland is being continually carried into Florida Bay and precipitated

on the bottom and in shoal areas, mangroves start to form small keys. By

including this shallow body of water, the Service will obtain the entire

eastern section of the rare Great White Herons' range, the only good

rookery of Roseatte Spoonbills in Florida, nesting areas for White

Ibises, Florida Cormorants, and other birts. It also is the home of the

Manatee or sea cow and Crocodile, and a bully spot to catch yellowtail,

redfish and snook.

Wandering White Pelicans spend their winter vacations

at Cape Sable, the "cape of sand", backed by hurricane-swept mangrove

swamps and tidal flats. Thousands of shorebirds and waterfowl, many Bald

Eagles, White Ibises, Wood Ibises, Egrets and Herons haunt the areas as

well as raccoons and elusive Florida Cougars. Three miles out in the

Gulf of Mexico from Cape Sable, the boundary continues in a

northwesterly direction. It passes the labyrinth at the mouth of the

Shark River where recently subsided land has left a maze of islands

through which only the most experienced navigator can pilot. Northward,

the boundary line goes by great mangrove and buttonwood forests rising

like a cliff from the water's edge. Major rivers draining the Everglades

empty into the Gulf along the western coast the Harney, Lostman, Broad,

Chattam, and others. At the headwaters of the rivers are mysterious

lakes and inlets where great rookeries of wading birds are located.

Little mangrove keys begin to appear about 40 miles

north of Cape Sable. They represent the southern fringe of that unique

country known as the Ten Thousand Islands, For about 15 miles more, the

park boundary follows along three miles from shore. It then dips to the

northeast through the mangrove keys joining the mainland at the mouth of

the Turner River. Some large shell mounds left by aboriginal inhabitants

are included in the park before the boundary swings to a point a few

miles north of the Tamiami Trail. The block of land both north and south

of the Trail is part of the Big Cypress region. This is favorite hunting

territory where Florida Cougar, the great Everglades Black Bear, Bobcat,

Deer, Turkey, Swallow-tailed Kite, and other rare birds and mammals are

found.

As the park boundary follows eastward the Tamiami

Trail, the above cypress gives way slowly to open prairies of the

Everglades. The line then angles south through sawgrass prairies to the

point of beginning.

Why include the region north of the Tamiami Trail?

One of the many reasons is water. With water as the basis for all life

in the proposed park, any deflection of flow north of the Trail would

cause profound ecological changes throughout much of the park area. A

drainage canal along the Tamiami Trail does this to some extent at

present, but it may be corrected. With water at a premium since drainage

operations were under taken at Lake Okeechobee, control of the cypress

and Everglades country north of the Trail is essential.

So, by following the boundaries of the proposed

Everglades National Park, we find that a country as flat as the

proverbial pancake still can have a surprising variation in the

landscape. It remains a wilderness in habited by Seminoles, a few

wandering trappers, some fishermen, and that is about all. The nature of

the land prohibits human intrusion except by boat or the few existing

roads. If fire is kept out, hunting is stopped, and water levels are

maintained, the Everglades National Park is capable of becoming the most

amazing wildlife sanctuary in the United States. Seed stock for almost

every native species of bird, mammal, reptile, amphibian, and plant

still is left and, with the fertility of the tropics, can soon start the

return to primitive conditions.

|