|

THE BLUE RIDGE PARKWAY

A New Element in Recreational Planning

By Stanley W. Abbott,

Acting Superintendent,

Blue Ridge National Parkway Project,

Roanoke, Virginia

Recent emphasis on planning regionally for recreation

draws attention to the simple fact that national park development so far

has been limited for the most part to the featured areas which are the

"end" of the motorist's journey from home. For the average family the

way is long to reach the wilderness, especially in the East where

travelers must drive their automobiles among trucks and buses through

miles of commercialized roadway before they "get away" and again as they

return. To the development of recreation the Blue Ridge Parkway is,

therefore, a new note -- something of a first answer to the national

park approach road.

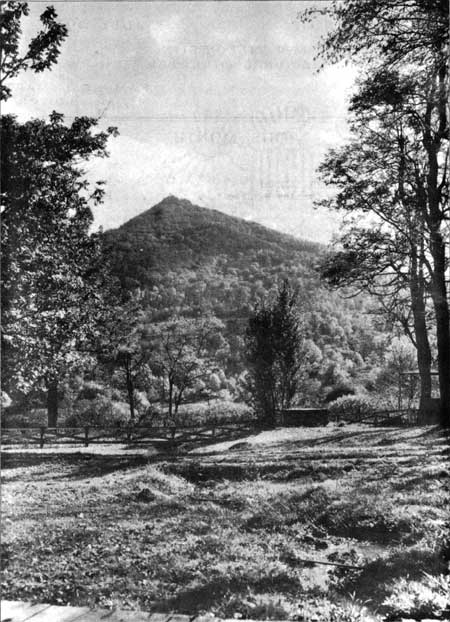

SHARP TOP, ONE OF THE PEAKS OF OTTER

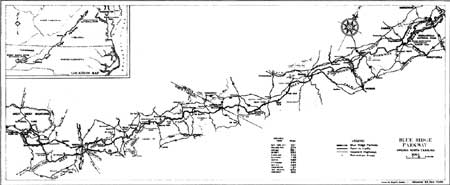

The project is 480 miles long, averages 2,500 feet in

elevation, and will connect Shenandoah and Great Smoky Mountains

National Parks. It is the longest road ever to be planned as a single

unit in the history of American road-building. But the real interest of

the work lies in the dramatic variety of the vast mountain country being

made accessible, the thought that the motorist will travel for nearly

the entire length of two southern states always in the invigorating

coolness of the high mountains, and that through this first tourway will

come the fusion of two of America's most popular national parks into one

huge recreational system. Mindful of the many cliffsides, chasms and

spur ridges that lay ahead to thwart passage of a modern motorway along

the Blue Ridge, more than one expert planner predicted that it would

"fall of its own weight" when this $30,000,000 proposal first was made

five years ago. Now, with more than 100 miles ready for traffic and an

additional 190 in various stages of construction, and with the entire

route plotted on survey maps a steady advance toward its completion

seems reasonably assured. Its character and usefulness should be amply

demonstrated during the next two years as added miles are opened to

connect a continuous route from Roanoke, Virginia, to Asheville, North

Carolina.

The completed portions, such as may be seen by

visitors to the work below Blowing Rock and Roanoke, will differ greatly

from the usual commercial highway principally because of the parkway

idea. Likewise, and because it constitutes a first adaptation of the

broad right-of-way to a rural region, it will differ from such parkways

as Colonial and Mt. Vernon, and those near New York City which have

proved so sound in the suburban plan. It will bear only remote likeness

to the Skyline Drive in the Shenandoah even though it was from the

enthusiastic reception of that road by the public that the Blue Ridge

project had its birthright.

(click on image for an enlargement in a new window)

According to the parkway principle, the states of

Virginia and North Carolina, through their highway departments, are

acquiring for the federal government what is in effect a recreational

area 480 miles long and about 800 feet wide. Through this ribbon-like

park is built the motorway, and instead of sign boards and hot dog and

gasoline shanties, a naturally beautiful roadway becomes possible of

preservation, and where despoiled, possible of landscape improvement. In

effect, an ever-to-be green, and, in places, a primitive cross section

of the eastern highlands has been set aside for motor recreation. The

acquisition of thousands of private tracts more or less in the immediate

path of the steam shovel has required the closest cooperation between

state and federal forces. Studies by the Service call for a taking which

varies in width from 200 to 1,200 feet, and the requirements must be

judged as much for effect upon the residual property as for control of

the roadside picture. Private and public roads, cattle crossings, water

rights, and phone and power lines seriously involve the entire economy

of many larger mountain properties. Relocation of these facilities must

be arranged or the entire holdings purchased outright. Those

considerations and the natural tendency of many mountain people to hold

to the old homes of their forefathers combine to make a more than

usually difficult problem of acquisition, especially if condemnation is

to be avoided.

The Blue Ridge Parkway is laid out expressly as a

route for the leisurely tourist, but there has been little compromise in

meeting the requirements of safety, reasonable speed, and ease of

driving. Viaducts, tunnels, retaining walls and other special devices of

the highway engineer have been employed in subduing the sharp curves and

steep grades that we associate habitually with the mountain road. This

maintenance of a high standard of modern road has meant the "scar" of

machine construction in certain rough and steep-sided mountains.

Occasionally the excavation to create the 30-foot road section mounts as

high as 100,000 yards to the mile. Technicians are confident

nevertheless that landscape and erosion control work, combined with

time, will largely erase this evidence of Diesel power and dynamite. For

the sake of safety, native stone and timber bridges carry the Parkway

over or under important transmountain highways and do away with the

crossing of traffic at grade. Operating policy will limit the use of the

drive to passenger cars only, eliminating the annoyance of the large

truck and bus.

In order to keep construction costs within reasonable

bounds while still maintaining standards of curvature and grade, and

what is more, to avoid excessive scar, it has been necessary to skirt

some of the more rugged regions with the result that the Parkway does

not exclusively follow the skyline, but assumes a changing position in

the mountains. Like the movie cameraman who shoots his subjects from

many angles to heighten the drama of his film, so the shifting position

of the roadway unfolds a more interesting picture to the traveler. The

sweeping view over the low country often holds the center of the stage,

but seems to exit gracefully enough when the Parkway leaves the ridge

for the more gentle slopes and the deeper forests.

The panoramic landscapes seem even bolder for these

contrasts. Of quite different character, but still of interest to the

overall pattern, are the quiet fields and pastures which make unusual

designs in many high land sections. Here among the strange bluffs and

crags and waterfalls an abandoned log cabin, or a water mill long past

its days of grinding grist, chronicles the human history of these very

old American mountains. As much as possible these featured players of

nature and of history on the Blue Ridge have been billed for continuous

performance, and funds made available to the Service have been used to

acquire many of them in their setting and well beyond the normal widths

of right-of-way. In places an area of 6,000 to 10,000 acres embraces a

whole group of mountains. Selected also for logical distribution along

the Parkway, roughly at 20-mile intervals, these parks will provide the

setting for wayside travel facilities. Several areas are being developed

now through the Civilian Conservation Corps and Emergency Relief

Administration work programs. Picnic and camp grounds, motor service

stations, coffee shops and modest lodges will complement those of the

tourist towns scattered through the mountains, rounding out a

self-contained motor vacation land.

Along with the provision of facilities for many forms

of active recreation, large areas in these parks will remain undeveloped

so that the adventurous may withdraw from the Parkway traffic to tramp

or fish in the unbroken forests. Among the notable geographic features

of the Parkway route in Virginia are the George Washington and the

Jefferson National Forests, the Peaks of Otter, and the Pinnacles of

Dan; and in North Carolina, Grandfather Mountain, Linville Gorge, the

Craggy Gardens, and Mount Mitchell, the highest elevation east of the

Rockies. Rounding Asheville the Parkway will dip downward to cross the

French Broad River and then will rise high in the Pisgah National Forest

to approach the Great Smoky Mountains, probably near the Qualla Indian

Reservation of the eastern Cherokees.

Plans for maintenance and protection of the Blue

Ridge Parkway by the Service call for headquarters areas at 60-mile

intervals, or in each third park. Management of traffic on the Parkway

and ranger patrol of an aggregate boundary of 1,000 miles, along which

abut many private holdings, necessarily will develop problems of

administration, certain elements of which will be peculiar to the

Parkway work. Take for example the problem of maintaining Parkway lands.

The charm of many sections in the Blue Ridge lies in the farm fields and

pastures. Should these cultivated areas or the Parkway strip itself be

allowed to return to forest indiscriminately, many of the fine views

would be lost. The Service can hardly expect to grow the corn and wheat,

or to tend the cattle in the pastures, and so has resorted to leasing at

nominal rentals those Parkway lands naturally adapted to cultivation. In

this manner the roadside picture will be maintained without cost to the

United States and better neighbors will be made of nearby farmers.

PARKWAY SEEN FROM ROCKY KNOB,

A Major Recreational Area in Virginia

|

The Blue Ridge Parkway is being built under contracts

supervised by the Public Roads Administration whose engineers have

prepared the plans collaboratively with the Service in accordance with

the interbureau agreement. Amid much talk of a nation-wide system of

parkways and freeways the steady advance toward completion of a pioneer

national tourway seems especially timely. While any national system

doubtless would concern itself primarily with motorways that will serve

as express regional routes, many planners believe that there is a place

for the road of the purely recreational type. Since the Blue Ridge

Parkway will provide days or weeks of well rounded vacation high above

the summer temperatures, remote from the towns and cities and yet within

a single day's travel for 60,000,000 persons, it should test amply the

soundness of the idea. Many officials see emerging from this and from

the Natchez Trace Parkway programs a strong case for a new means of

bringing national parks closer to the people.

|