|

(click on image for an enlargement in a new window)

FATHER MILLET CROSS

America's Smallest National Monument

By Thor Borresen,

Junior Park Research Technician,

Colonial National Historical Park

Where the mighty Niagara River empties into Lake

Ontario there is a small, projecting piece of land. Its entire area is

approximately 20 acres and yet, to possess 12 of those acres, three

nations fought and battled for more than 100 years --- 1687-1814. Inside

the present enclosure of Old Fort Niagara, which rests on the piece of

land (pictured across these two pages; Web Edition Note: click on

above image for an enlargement of this entire image), is a bronze

cross 18 feet high with an arm of eight feet. On the arm is the

inscription

REGN. VINC. IMP. CHRS.

which stands for "Regnat, Vincit, Imperat, Christus."

The one-eighth acre on which the cross is located (shown by the arrow

and circle in the photograph) constitutes the whole of the national

monument to Father Pierre Millet who, on Good Friday in the year 1688,

reverently blessed the first wooden cross erected to give thanks for the

12 living and immortalize the 88 dead men who had manned the fort during

the preceding winter of starvation. The monument was set aside by

presidential proclamation on September 5, 1925, and the bronze cross was

presented by the New York State Knights of Columbus in 1926.

The Niagara region is world renowned today for its

famous cataract, but its early history is a vigorous, colorful one. The

Iroquois name for Niagara was spelled in several different ways --

"Onguiaahra," "Ongiara" (1), and "Onygara," the latter the most commonly

used by the English. In 1687 "Niagara" began to come into vogue and its

popularity was assured shortly after by Corronelli's map (2), although

as late as 1724, the variation "Jagara" was used on Colden's map (3).

The first white man on record who acquired knowledge of the mighty

cataract was Samuel Champlain, the French explorer who, in 1603,

ascended the St. Lawrence River, then known as the Iroquois or Catarakui

(4). It is generally recognized, however, that he never visited Niagara

River and that the map for which he gathered information in 1603 and

published in France in 1612 (5), showing Lake Ontario and the Niagara

River, was drawn on hearsay of the Indians. When he actually visited

Lake Ontario in 1615, he did so by traveling the length of the Ottawa to

Georgian Bay; at the south end of the bay he made portage over to Lake

Simcoe and from there overland until he struck the River Trent, which he

followed to its mouth in the Bay of Quinte; then, following that bay to

the Upper Gap, he crossed Lake Ontario to what is known today as Mexico

Bay (6). The map of his travels in 1615 was not published until 1632,

and while it shows a slight change in the river's position from his map

of 1603, neither the falls nor the river are placed correctly (7). Up to

1640 only traders and missionaries had seen the river and no attempts to

inhabit the area had been made by white men.

|

From the earliest descriptions by both red men and

white, the plateau where the present Old Fort Niagara and the cross are

situated was devoid of trees. The Indians used it for centuries as a

camping and meeting place and during those years all growth undoubtedly

was sacrificed for camp fires. A clearer understanding of the important

part the region played in the travels of the Indians may be gained by an

examination of the map at the bottom of this page (Web Edition Note:

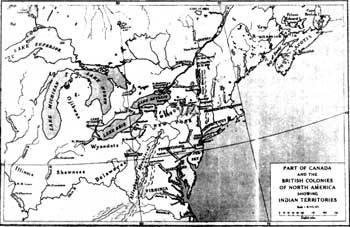

at left) (8). The Indians coming from the upper lakes followed the

Niagara River from Lake Erie to below what is now Buckhorn Island in the

upper Niagara, or the La Salle section of Niagara Falls, New York.

(There is today a four-lane highway over this route which has been known

for years as the Military Road.) They again placed their canoes in the

Niagara slightly below the point where now is situated the Lewiston and

Queenston suspension bridge. From there they followed the lower Niagara

to its mouth where it enters Lake Ontario, seven miles below Lewiston,

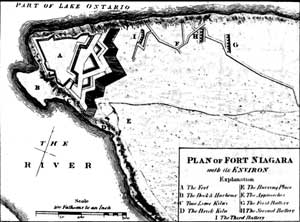

New York. At "B" on Captain Pouchot's map (below) is shown a piece of

land projecting into the river. It is only from three to five feet above

the flow of the stream and was an ideal place for hauling out canoes.

The plateau (see A) where the fort stands is 23 to 26 feet above the

lake level and afforded an excellent stopover when storms did not permit

the frail Indian boats to enter the lake.

|

The first white man known to begin construction on

the site was René Robert Cavelier, more famous as the Sieur de la

Salle. On May 12, 1678, he had been granted by the King of France (9) a

patent to trade with the Indians. This trade was to be limited, however,

to the western and southern tribes that could not reach Montreal and

Quebec with their stock of furs. The Ottawa River, having numerous

portages, was not a suitable waterway for La Salle's scheme of

large-scale trade, but the Niagara was ideal for it permitted large

vessels to go all the way from Fort Frontenac (Kingston, Canada) to

Lewiston. At the latter post he placed a magazine, with another at La

Salle, New York, in the upper Niagara, where he built the

Griffin, the first sailing vessel on Lake Erie, estimated by

various historians at 40 to 60 tons. The seven miles between the upper

and lower magazines was the only portage from the Great Lakes to

Montreal. For this reason the Niagara River has been called the "Gateway

to the West" [See map at right] (10).

La Salle realized, as the Indians did, the value of

the small harbor at the mouth of the river. To make it secure he

constructed a small fort where the present Old Fort Niagara stands. It

consisted of two 40-foot-square redoubts and one magazine, all

constructed of logs laid horizontally one on the other, the whole joined

by palisades. It was called Fort Conti in honor of Prince Conti, a

member of an old Italian family who had recommended Henri Tonty to La

Salle. Tonty was one of La Salle's staunchest supporters throughout his

entire exploratory career. The fort was completed sometime in the early

spring of 1679 but was burned later in the year through the carelessness

of a sergeant in charge of the garrison. La Salle did not rebuild the

storehouses and stockades, and it was not until the summer of 1687 that

the place was fortified again by the French.

The Iroquois had tolerated La Salle, but they were by

no means tolerant of the French explorers and traders in general; they

did not heed the peace treaty signed by the French and English at

Whitehall on November 26, 1686, an agreement which did not establish any

defined borders between the two nations' holdings, or prevent either

country from warring on any of the native tribes. Denonville, Governor

of Canada, claimed as part of French colonial possessions all the lands

bordering the Great Lakes and those along the Ohio and Mississippi

Rivers as far as Louisiana. The main trade route to these possessions

was by way of Lake Ontario and Lake Erie, with the portage at Niagara.

Among the most troublesome Indians along the route were the Senecas, the

leading tribe of the Iroquois Confederacy, whose territory bordered the

lakes of Ontario and Erie.

Denonville decided in 1687 to destroy the Senecas'

power and to bring them definitely under French domination. On June 13

he left Montreal with 800 troops. The number had increased to nearly

2,000 by the time he reached Fort Frontenac, where he remained until

July 4 when he left with a flotilla of more than 400 canoes for

Irondequoit Bay (Baye des Sables) (11). The Indians themselves destroyed

their villages at the approach of the French, leaving the enemy the

satisfaction of damaging only the gardens and food supplies. They

escaped actual annihilation by keeping out of the Frenchmen's way. On

July 24 Denonville returned to his place of embarkation, leaving there

for Niagara. Determined to retain a foothold in the Seneca country, he

began construction of a fort on the same site on which La Salle's

defenses had stood nine years before. According to the journal of De

Tregay, lieutenant of the garrison and its surviving commander, Madame

Denonville accompanied her husband on the entire journey. If she did so,

she was the first white woman whose presence on the Niagara is recorded.

One of the officers with Denonville's expedition, Baron de la Hontan,

describes the work as a "fort of pales, with four bastions," which

"stands on the south side of the Straits of Herrie [Erie] Lake, upon a

Hill, at the foot of which that Lake falls into the Lake of Frontenac

[Ontario]."

When Denonville left Niagara, he promised supplies

would be sent back to the 100-man garrison immediately upon his arrival

in Montreal. As the season advanced and no supplies arrived, the

garrison was in a dangerous situation. The Indians had not been subdued,

and no help could be expected from them. On the other hand, they

ambuscaded and tried to destroy the French whenever they ventured out to

hunt or gather wood for their fires. Chevalier de Tregay tells in his

journal of the futile attempts by the men to take fish from the lake.

The garrison was on the verge of starvation when the barque arrived with

provisions. It was not until the sails of the ship were disappearing

against the horizon on its return to Kingston that the men became aware

of the condition of the supplies. They were all spoiled, unfit to eat.

De Tregay tells of the ruined provisions and how the garrison faced

winter with no food fit for human consumption. With hostile Indians on

one side and water on the other, their fort was more a prison than a

protection. Scurvy and starvation soon took their toll. De Tregay

continues:

The wood choppers, one day, facing a storm, fell in

the drifts just outside the gate; none durst go out to them. The second

day the wolves found them - and we saw it all (12).

By the end of February 60 had died. One morning De

Tregay heard Commander de Troyes mumbling names of loved ones. Soon

after he joined the major portion of the garrison. De Tregay himself was

on the verge of succumbing to starvation when, suddenly, a huge savage

in full war regalia appeared before him. Too weak to offer resistance,

he prepared himself for the inevitable, but instead the Indian held

before him food, and in the language of the Miamis said "Eat!". So it

was that a few friendly Miamis Indians from the Ohio Valley rescued the

12 survivors of the garrison of Fort Denonville which had consisted

originally of 100 men.

It was on Good Friday, 1688, that Father Millet, a

pioneer missionary who went to Canada in 1667 from his native France,

directed the garrison survivors to plant a huge cross in the center of

the square forming Fort Denonville to commemorate the men who had died

and give thanks for those who had survived. The dimensions of the cross

and its inscription were the same as those mentioned above in a

description of the permanent bronze substitute erected on the site in

1926.

Pierre Millet, born in 1635 at Bourges, the

approximate geographical center of France, was educated for the church

and, when 32 years old, sailed for Canada as one of the early priests

whose heroic devotion took Christianity into America's virgin

wilderness. "He served about 15 years as a missionary among the Onondaga

and Oneida Indians within what is now the State of New York," said the

presidential proclamation which established the national monument, "and

subsequently became a chaplain in the French colonial forces." He died

in Quebec.

During the summer of 1688 another peace treaty was

signed between England and France, as well as an agreement between the

Iroquois and the French to stop further violence on the frontier. In

this agreement the French consented to the withdrawal of their forces

from the Niagara region and to the destruction of the fort except for

the cabins and quarters, which were to be left standing for the use of

the Indians. The itemized list of buildings left by the French helps to

picture what this ancient fort looked like:

"ITEM, A cabin in which the Commandant loged,

containing a good chimney, a door and two windows furnished with their

hinges, fastenings and locks, which cabin is covered with forty-four

deal boards, and about six other boards arranged inside into a sort of

bedstead.

"ITEM, In the immediate vicinity of said cabin is

another cabin with two rooms having each its chimney; ceiled with

boards, and in each a little window and three bedsteads, the door

furnished with its hinges and fastenings; the said cabin is covered with

fifty deal boards and there are sixty like boards on each side.

"ITEM, Right in front is Rev. Father Millett's cabin

furnished with its chimney, windows and sashes; with shelves, a bedstead

and four boards arranged inside, with the door furnished with its

fastenings and hinges, the which is of twenty-four boards.

"ITEM, Another cabin opposite the cross, in which

there is a chimney, board ceiling, three bedsteads, covered with

forty-two boards, with three like boards on one side of said cabin,

there is a window with its sash and a door furnished with its hinges and

fastenings.

"ITEM, Mother cabin with a chimney, a small window

with a sash and door; covered with thirty deal boards; there are three

bedsteads inside.

"ITEM, A bakehouse furnished with its oven and

chimney partly covered with boards and the remainder with hurdles and

clay; also an apartment at the end of said bakery containing two

chimneys; there are in said bakery a window and door furnished with its

hinges and fastenings.

"ITEM, Another large and extensive frame building

having a double door with nails, hinges and fastenings, with three small

windows; the said apartment is without a chimney; 'tis floored with

twelve plank (Madriers) and about twelve boards are arranged inside;

without, 'tis clap-boarded with eighty-two plank.

"ITEM, A large storehouse covered with one hundred

and thirty boards, surrounded by pillars eight feet high, in which there

are many pieces of wood serving as small joists, and partly floored with

several unequal plank. There is a window and a sliding sash.

"ITEM, Above the scarp of the ditch a well with its

cover."(13).

The story of the present Old Fort Niagara does not

begin until about 1725, and is one to be told another time. The writer

of this article was a member of the staff during the restoration of Old

Fort Niagara, from 1926 to 1934, and had charge of several minor

archeological excavations. During this work skeletal remains were

encountered. Some of the burials were only 11 inches below the surface

and changes in the road system necessitated the removal of a few of

them. What portion of these represents the period of starvation, no one

has determined. During the French and English war, when General Pridaux

laid siege to Fort Niagara in July, 1759, many of the French of the

garrison were killed and buried within these walls; and during the War

of 1812, several casualties occurred, their internment most likely

taking place on the spot.

During the summer of 1934, a large monument was

erected within the grounds to commemorate the Rush-Bagot Treaty of 1817

between Canada and the United States. A suitable niche was constructed

in the center of this memorial and all the remains, sealed in an

aluminum container, were placed there, the whole marked with an

inscribed stone.

(1) Justin Winsor, editor, Narrative and

Critical History of America (Boston [copyright, James R. Osgood and

Company, 1884]), IV, 247.

(2) Justin Winsor, Cartier to Frontenac:

Geographical Discovery in the Interior of North America in its

Historical Relations, 1534-1700 (Boston, 1894), 334.

(3) Justin Winsor, editor, Narrative sad Critical

History of America (Boston, 1887), V, 491.

(4) Justin Winsor, Cartier to Frontenac,

op. cit., map, "A Plan of the Fort and Day of Frontenac with

adjacent Countries," [published in the London Magazine in 1758],

335.

(5) Edward T. Williams, A Short History of Old

Fort Niagara (published by Old Fort Niagara Association, Inc.,

1929), 11; westerly portion of map reproduced in Winsor's Narrative

and Critical History, op. cit., IV, 381.

(6) Justin Winsor, editor, Narrative and Critical

History of America, op. cit., IV, 125-126; "Champlain's

Route, 1615," map on p. 125.

(7) Easterly and westerly portions of Champlain's

1632 map reproduced in Winsor's Narrative and Critical History,

op. cit., IV, 386-387.

(8) Photocopy of map, "Plan of Fort Niagara with its

Environ," by Pouchot, 1759; taken from Memoir upon the Late War in

North America, Between the French and English, 1755-1760, by Pouchot

([translated and edited by Franklin B. Hough], Roxbury, Mass., 1886),

II, 152.

(9) Justin Winsor, Cartier to Frontenac,

op. cit., 256.

(10) Photocopy of map, "Part of Canada and the

British Colonies of North America showing Indian Territories," from

The Faithful Mohawks by John Wolfe Lydekker (New York, 1938), ff.

206.

(11) Pouchot, op. cit., II, 124.

(12) Williams, op. cit., 24.

(13) Ibid., 25-26.

|