|

WINTER BIRDS OF ACADIA

BY MAURICE SULLIVAN,

Park Naturalist,

Acadia National Park, Bar Harbor, Maine

PURPLE FINCHES AT ACADIA

|

There is not a sound save the wind in the spruces and

pines and firs The pure white new-fallen snow lies a foot deep on the

level. It is a dry fluffy snow, each flake a perfect star, as if the

heavens had sent down a shower from the Milky Way. The music of the wind

in the trees is punctuated occasionally by a dull thud and a swish as

some overburdened bough is relieved of its accumulation of snow and

springs back to its normal position. Fine tracks of some mouse or

larger tracks of the red squirrel are the only evidence that any

animal has penetrated the deep spruce forest, dark, silent and deserted.

If Champlain had first landed here in winter we well

could understand the reason for calling this place Mount Desert Island.

The birds which are so numerous in summer are now far away in warmer

regions where the food is more plentiful. It is lonely; the forest needs

inhabitants; one's own footfall is muffled. Thoughts of far-off places,

of isolated lighthouses, of early pioneers, invade the mind.

Two branches creak faintly, almost unheard. The "Ti,

ti, ti, ti" comes nearer, a busy Golden-crowned Kinglet searching

everywhere for insect eggs. If two hen's eggs and three slices of bacon

suffice me for a meal, do you suppose two moth eggs and three dried

spiders satisfy his hunger? I doubt it. He has to maintain a higher

temperature than I do, and is far more active. He probably consumes

hundreds of insects eggs and dead or numbed specimens every day. And a

good service he renders the forests.

From the rear a Chickadee suddenly introduces itself

with "Chicka-dee-dee-dee." It is the state bird of Maine and one of the

most common winter land birds in Acadia. In all probability these two

birds are all that will be seen among the evergreens, although an

erratic band of Crossbills, either White-winged or Red, may appear.

(click image for an enlargement in a new window)

|

The winter birds of Acadia are not dwellers of the

deep forest, but frequent the more open hardwood areas, the fields and

gardens, and, of course, the unfrozen ocean. There probably are more

species of land birds on Mount Desert Island now than there were when

the island was in a primeval condition. Before white man came it most

certainly lacked the introduced Starling, English Sparrow, Ring-necked

Pheasant and Rock Doves which now are present. It has lost certain

species, no doubt, but there the record is not so definite. Whether the

Passenger Pigeon, Spruce Grouse, Wild Turkey, Golden Eagle, and perhaps

other land birds once overwintered in Acadia is unknown, but the

presence of the Golden Eagle and Spruce Grouse could be expected.

The white man cleared the forests, planted gardens,

carried on agriculture, and permitted more grasses, weeds and

hardwoods, such as wild cherry, gray birch, and berried shrubs, such as

raspberry, blackberry, blueberry, elderberry and huckleberry, to

flourish in burned-over and cleared areas. He planted barberry, sumac,

roses, hawthorn, mountain ash, wahoo, and other berried shrubs. These

are particularly numerous on the large summer estates. The open fields

are thereby made more attractive to Juncos, Song Sparrows, Redpolls and

White-throated Sparrows. The feeding stations maintained at many homes

are perhaps responsible for some birds overwintering in areas where

natural food would not be sufficient otherwise.

Nuthatches (both White-breasted and Red-breasted),

Tree Sparrows, Song Sparrows, and sometimes Purple Finches,

Goldfinches and Pine Siskins, are entirely or in part dependent on feeding

stations. The hardy Ring-necked Pheasant needs artificial feeding

because he has not learned to eat birch buds as does his relative, the

Ruffed Grouse. The Grouse has another adaptation which the Pheasant

lacks. At the approach of cold weather small projections develop on the

toes of the Ruffed Grouse. These are his snowshoes and enable him to

travel more easily. The Indian may have invented the snowshoe, but he

must have received his idea from the Grouse or the Snowshoe Rabbit.

Robins, Pine Grosbeaks and Mocking Birds, which sometimes overwinter,

must be grateful for the cultivated berry-bearing shrubs and trees.

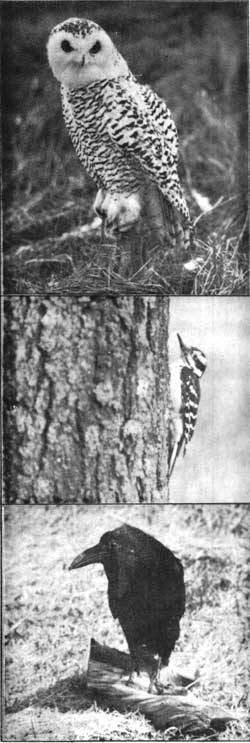

Among the Woodpeckers a Downy is the only one that

can be found regularly. The Hairy can be seen occasionally, but it is a

rare experience to find either the Three-toed or the Pileated. It is

likely that woodpeckers were more plentiful when the island was better

forested and there were more dead and dying trees.

The numbers and even the presence of certain northern

birds cannot be predicted. During the winter of 1935-36 Pine Grosbeaks

were common, but since then they have been absent or rare until this

winter then they appeared in considerable numbers, one flock containing

more than 100 birds. When they first were seen in November (1939) they

fed on the seeds of the white ash, carefully shelling out the seeds from

the rest of the winged fruit. Seeds of the cranberry tree (Viburnum

opulus) next were consumed. Each bright red berry contains one seed

which was carefully extracted and eaten, the pulp and juice often

giving a brilliant color to the snow beneath the bush in which the

Grosbeaks had fed. So tame are these visitors from the sparsely settled

regions of the north that one of the local bird-banders succeeded in

approaching two feeding birds and capturing them with his hands.

Top, Snowy Owl; center, Hairy Woodpecker, and bottom, Raven, at Acadia

National Park. Owl and Raven are mounted.

|

Excepting for Bald Eagles, the raptorial birds are

poorly represented in winter. A Red-tailed Hawk was shot recently at

the Southwest Harbor town dump, where it probably was hunting for rats

and mice, but it may have been scavenging. The American Rough-legged

Hawk is an occasional visitor but less common than the Goshawk, which is

known to nest in the park.

Among the Owls the Snowy is perhaps the most

interesting because of its size, habits and coloring [See photograph at

right]. A few probably wander down every winter, often keeping to the

outer islands and shores. They arrive occasion ally in considerable

numbers, and although shy, many are shot because of their conspicuous

white feathers and their habit of diurnal hunting in the open areas.

The appearance of these Owls in large numbers seems to coincide with a

scarcity of lemmings and hares in the far north, although other factors

may be involved.

Other Owls include the Barred Owl,

Great Horned Owl, Saw-whet or Acadian Owl, Richardson's Owl and Hawk Owl. Of

these the Barred Owl and Great Horned Owl

are reported most often, due possibly to size and to the fact that both

are "hoot owls". The only specimen of Richardson's Owl was obtained by

some boys hunting a Christmas tree. The confiding Owl was killed with

their hatchet.

Other migrants from the north are the Redpolls,

nesting in boreal zones as far as the tree limit or beyond, but

overwintering in New England and as far south as North Carolina,

Tennessee and Missouri. It is most common at Acadia in late winter,

being found in open fields, about barns, and in thickets of gray birch.

Its tameness and confiding manner make it a favorite with bird lovers.

It is fond of visiting feeding stations.

Of the 64 species recorded in six

Christmas bird censuses, 25 are water birds. Of these

the American Eider is probably the most numerous and the Herring Gull

the most widespread. The Eiders may be seen riding the waves and diving

for food around ledges such as the one near Otter Cliff. Herring Gulls

are scattered all along the shore, but are numerous near the fishing

centers in Southwest Harbor and McKinley where they pick up offal from

the fish-cleaning operations, thereby performing an indispensable

service. So common is the Herring Gull that few persons are aware that

it was in danger of extinction about 40 years ago. The traffic in

feathers was so lucrative at that time that almost any large bird

furnished millinery decorations. Gulls were killed by the thousands.

Action by the National Association of Audubon Societies finally stopped

the slaughter and Gulls now have increased to such an extent and are so

numerous in some localities that control measures, usually the

puncturing of eggs, are required. Reduction of natural predators, such

as Mink, Eagles, Crows, and possibly angler fish, has permitted the Gull

to increase.

The Great Black-backed Gull is boss among the Gulls

and for that reason is usually by himself, separated from other Gulls by

at least a "safe distance". He is larger and more powerful, but with

wings which are blackish on the upper surface. At least one pair is

known to exist in this region. Iceland and Glaucous Gulls are to be

expected every winter but are not very common. Both are boreal birds

nesting in the Artic regions and wintering as far south as the New

England states. Careful searches among the many Herring Gulls probably

would reveal the presence of these two Gulls.

Of the other Ducks, the American Golden-eye, the Old

Squaw and the Black Ducks are usually most numerous. The common name for

the Golden-eye is "Whistler", due to the sound of his fast-beating

wings. He is typical of the Maine coast in winter as he feeds in salt or

fresh water but nests in holes in trees on inland lakes and streams.

Whenever you visit the seashore you probably can hear the Old Squaws if

they are near, because they are the most garrulous of sea Ducks. Their

generic name, Clangula, has the same root as "clangor" and "clang". It

is a heavily feathered, hardy bird, said to be able to dive to depths

exceeding 150 feet.

For years, "gunning for coots" has been the favorite

wild fowl hunting among coastal fishermen, to whom all Scoters are

"coots". The Scoters arrive in the autumn before many other species and

in times past have been so numerous that barrels of them were salted

down for winter use. Down and feathers from Scoters and other sea birds

were sold or used at home for beds and pillows. I have such a feather

bed, acquired from an old sea captain. Next to pure eider down, nothing

could be warmer for our cold winter nights in Acadia.

Among the common Ducks, the Black Duck is esteemed

highly for eating. It is a good-sized Duck and has a fine flavor,

especially when it has fed in fresh water as it does until ice covers

the lakes. It is one of the few Ducks which nests locally, being

somewhat common on beaver flowages and other suitable areas.

The little Dovekie is one of the most interesting

visitors to our shores, arriving about the middle of November. A

"blow" occurs occasionally just when the migration is in full swing and

dozens of these Little Auks are forced ashore, or even miles inland,

where they are found dead or too exhausted to rise.

The Dovekie is ordinarily found offshore where it

gets sufficient food and is well able to withstand all save the fiercest

"blows". In March they start their slow migration hack to Greenland,

Baffin Island, and similar areas in the Arctic where they are welcomed

by the Eskimos. All winter the natives have been in darkness, living on

dried fish, blubber, an occasional hare or fox, and perhaps a little

food obtained from a trading post. The Dovekies suddenly begin to

arrive. All is commotion as the women rush for nets, the boys seek

rocks, and the men bring forth guns and bows and arrows. In all

probability the first birds killed will be eaten raw, directly from the

skin, while the body still is warm and bleeding. The natives are

ravenous for fresh meat and the Dovekies supply it in quantity. Eggs are

utilized in season and the surplus birds are stored, insides, feathers

and all, in a seal skin to be kept for many months and eaten as

needed.

The north wind sings down the fireplace and around

the corner, a reminder that winter is still with us here at Acadia,

despite the bright sunshine outside. It has rained but once in the last

six weeks [Up to February 1, Ed.], the thermometer has stood between 10

and 30 degrees above zero most of the time, and winter will be with us

until April. Not until late April and early May will the Warblers return

in number.

The writer hopes that no one will be disappointed if

he has failed to write about a favorite bird. If the reader seeks

further information he may consult the accompanying summary. A good

book, such as Forbush, Birds of Massachusetts and Other New

England States, will supply details.

CHRISTMAS BIRD CENSUSES SUMMARY

| 1933 | 1934 |

1936 | 1937 |

1938 | 1939 |

| Common Loon | | 6 | 3 | 2 | 9 | 3 |

| Red-throated Loon | | | | 6 | | |

| Holboell's Grebe | 3 | | 7 | 3 | 5 | 2 |

| Horned Grebe | | 4 | 21 | 7 | 1 | 3 |

| European Cormorant | | 13 | 91 | 34 | 6 | 8 |

| Black Duck | 71 | 65 | 17 | 550 | 1024 | 225 |

| Greater Scaup | | | | 7 | | 20 |

| Lesser Scaup | | | 1? | | 31 | |

| American Golden-eye | 8 | 23 | 92 | 294 | 312 | 320 |

| Barrow's Golden-eye | | | | | 25 | |

| Buffle-head | | | 36 | 28 | 32 | 41 |

| Old Squaw | 28 | 20 | 81 | 68 | 205 | 115 |

| American Eider | | | 800 | 404 | 604 | 1000 |

| White-winged Scoter | 2 | 29 | 9 | 20 | 57 | 59 |

| Surf Scoter | | | 2 | | | 1 |

| American Scoter | | | 10 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| American Merganser | | | 3 | 1 | 26 | 3 |

| Red-breasted Merganser | | 1 | 23 | 11 | 31 | 20 |

| Red-tailed Hawk | | | 1? | 1 | 1 | |

| Bald Eagle | 1 | 7 | 6 | 10 | 3 | 8 |

| Duck Hawk | | | | | | 1 |

| Ruffed Grouse | 1 | 1 | 9 | 9 | 6 | 3 |

| Ring-necked Pheasant | | | | | 8 | 3 |

| Purple Sandpiper | | | | | 150 | |

| Great Black-backed Gull | | 6 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 3 |

| Herring Gull | 164 | 10 | 208 | 250 | 203 | 200 |

| Ring-billed Gull | | 115 | | 1 | | |

| Brunnich's Murre | | | | | 1 | |

| Dovekie | | 5 | | 5 | | |

| Black Guillemot | | | 34 | 8 | 1 | 7 |

| Rock Dove (pigeon) | | | 16 | | 13 | 40 |

| Barred Owl | | | | | | 1 |

| Kingfisher | | 1 | | | | |

| Hairy Woodpecker | | | 1 | | 7 | 2 |

| Downy Woodpecker | 10 | 1 | 12 | 4 | 8 | 4 |

| Arctic Three-toed Woodpecker | 1 | | | | | |

| Blue Jay | | | | 1 | | 2 |

| Raven | | 3 | 6 | 2 | 1 | 12 |

| Crow | 13 | 49 | 29 | 50 | 22 | 20 |

| Black-capped Chickadee | 18 | 29 | 41 | 75 | 34 | 29 |

| Acadian Chickadee | | | 3 | 3 | | |

| White-breasted Nuthatch | | | | 4 | 1 | 2 |

| Red-breasted Nuthatch | 17 | | 2 | 30 | 4 | |

| Brown Creeper | 4 | | 6 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Winter Wren | | 1 | | | | |

| Mockingbird | | | 1 | | | 1 |

| Robin | 3 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 2 |

| Golden-crowned Kinglet | 16 | 13 | 48 | 27 | 23 | 15 |

| Northern Shrike | | 1 | | 1 | | 1 |

| Starling | 10 | 63 | 49 | 21 | 122 | 16 |

| English Sparrow | 2 | | 2 | 40 | 22 | 8 |

| Bronzed Grackle | | | | | 1 | |

| Purple Finch | | | | | 2 | |

| Pine Grosbeak | 10 | | | | | 150 |

| Pine Siskin | | | | 10 | 35 | 16 |

| Goldfinch | | | | | 7 | 14 |

| Red Crossbill | 21 | | | | | |

| White-winged Crossbill | 27 | | 2 | 20 | 85 | |

| Slate-colored Junco | 4 | | 2 | | | 3 |

| Tree Sparrow | 10 | 4 | 16 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| Chipping Sparrow | | | 1 | | | |

| White-throated Sparrow | | 1 | 8 | 1 | 1 | 4 |

| Fox Sparrow | | | 1 | 1 | | |

| Song Sparrow | 2 | 1 | | 2 | 1 | 2 |

|