| ||||||||||

| Intro | Author | Subject | Volume | Volume/Title | NPS | |||||

|

Volume IV - No. 6 |

June, 1940 | |||

|

THE ROLE OF ARTILLERY

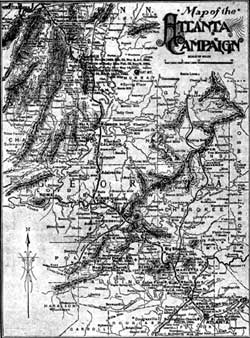

In The Atlanta Campaign By B. C. Yates, Superintendent, Kennesaw Mountain National Battlefield Park "The nature of military operations in a country like ours is peculiar, and often without precedent elsewhere," wrote General Barry, Sherman's chief of artillery.1 "It is generally unfavorable to the full development and legitimate use of artillery. This is eminently the case in the West, where large tracts of uncleared land and dense forest materially circumscribe its field of usefulness and often force it into positions of hazard and risk, The services of the artillery throughout the whole campaign have been conspicuous. The western life of officers and men, favorable to self-reliance, coolness, endurance, and markmanship, seems to adapt them peculiarly for this special arm. Their three years' experience in the field adds important elements to their efficiency and has combined to render the artillery of your command unusually reliable and effective. At Rocky Face Ridge, Resaca, Kenesaw, and amid the varied and bloody operations before Atlanta, it sustained its appropriate share of the work most creditably. Its practice at Rocky Face Ridge and Kenesaw Mountain, where at unusual elevation it was called upon to silence or dislodge the enemy, was extraordinary. Abundant proof of this was obtained from personal inspection of the enemy's works after we gained possession of them, which proof is fully confirmed by the concurrent acknowledgement of the enemy." General Barry thus describes the general operations of his arm during the Atlanta Campaign. In the same report he discloses that the artillery force which took the field with Sherman May 5, 1864, contained 50 batteries and 254 guns, a considerable reserve being stationed at Nashville and Chattanooga.

The Federal army was reduced to guns of four calibers consisting of light 12-pounder howitzers, Napoleons, 10- and 20-pounder Parrotts, and 3-inch regulation rifles. As for the efficiency of these guns, General Barry observes: "The 10- and 20-pounder Parrotts and the 3-inch wrought-iron guns have fully maintained their reputations for endurance and for the superior accuracy and range expected from rifled guns. The light 12-pounder has more than ever proved itself to be the gun for the line of battle, where facility of service and effectiveness of solid shot, spherical case, and canister is most required - - - The amount of ammunition furnished both field and siege guns was always abundant, and it was generally supplied in serviceable condition and of the best description - - - The batteries were efficiently horsed and well supplied with caissons, battery wagons, and traveling forges, and rarely had at any time on hand a less amount of ammunition than 400 rounds per gun." General Johnston's Confederate army had 187 pieces of artillery at the beginning of the Atlanta Campaign. While some rifled guns were included the majority of the Confederate guns were smooth bore, chiefly napoleons, which had a shorter range and less accuracy of fire; nor were the Confederates blessed with the abundance of ammunition available to the Federals. Light 12-pounder howitzers were employed by both armies. These guns with a high looping trajectory were particularly valuable in firing upon elevated positions. The napoleons were sturdy guns particularly valuable since they could be used for firing shot, case, and cannister, and thus could be employed against both fortifications and troops. The rifled guns, including the regulation 3-inch rifles and 10- and 20- pounders, exhibited excellent accuracy and long range, Projectiles employed included solid shot, used against strong fortifications; shell, which is a hollow exploding projectile; case, which is an exploding projectile containing smaller pellets which scatter in all directions; and canister and grape, which well could be described as huge shotgun charges. Sherman brought to the field approximately 100,000 troops. Opposing him, the Confederates had 50,000 men, and, thus outnumbered, were on the defensive, Sherman desired to keep the Confederate army so busily engaged that no troops could be detached to aid Lee or other southern armies, and he wished also to destroy all military resources, supplies, factories, and communications, which were providing needed equipment. A natural physical objective was Atlanta, Georgia, since it was a focal point for railroad communication and possessed a number of mills and factories. Further, the fact that the Western and Atlantic Railroad from Atlanta to Chattanooga could be used as a line of supplies made a movement in this direction particularly desirable for Sherman. Johnston received his supplies and food from Atlanta and therefore sought to remain in the vicinity of this railroad. It can be seen readily that the location of the railroad controlled troop movements during the campaign.

Sherman, upon his advance from Chattanooga, found the Confederates strongly entrenched on Rocky Face Ridge just north of Dalton, Georgia. Here he utilized artillery and skirmish lines to divert the attention of the Confederates while a rapid flank movement was made through Snake Creek Gap toward Resaca. The success of the movement forced the Confederates back to Resaca where they entrenched on a semicircle of hills protecting the town. The Confederate position was fairly strong. The Federals advanced, however, and secured a position for their artillery on the right flank. The guns could command the bridges across the Oostanaula River at Johnston's rear. This fact, coupled with a Federal flanking movement, forced the Confederates to retire south of the river. After minor actions at Adairsville and Cassville, Sherman determined upon a flank movement with his army toward Atlanta. Divining his strategy, the Confederates intercepted the movement at New Hope Church, arriving there a short time before Sherman's columns. Sherman, realizing the importance of this road center, threw wave after wave of troops upon the Confederate position. Stewart's Division of Hood's Corps handily repulsed these ferocious assaults, and Hood, in writing of this engagement asserted: "Too much praise cannot be awarded to the artillery under the immediate direction of Col. Beckham, which did great execution in the enemy's rank and added much to their discomfort here."2 After these unsuccessful assaults, Sherman moved to the railroad to shorten and improve his line of communications, the Confederates following and entrenching in the vicinity of Kennesaw Mountain. Sherman developed these positions, using his artillery to brush aside the Confederate skirmish lines, a procedure typical of the Atlanta campaign. As soon as the main Confederate positions were determined and studied, Federal batteries were put in place in the vicinity of all salients or angles in order to fire along the trenches and render them untenable. Skillful use of artillery contributed materially in forcing the Confederates to evacuate salients at Pine Mountain, Gilgal Church, and the Latimore Farm, and forcing them to entrench on Kennesaw Mountain and the ridges running north and south of it. Developing this position, Sherman determined to make a major assault on the Confederate center in the hope that he could crush Johnston's Army and bring the campaign to a speedy conclusion. The attacking columns were aimed toward two points, one at Little Kennesaw Mountain, the other at a salient in the Confederate line defended by General Cheatham. Before the assault the Federals used an artillery barrage; and when the assaulting columns moved forward, the Confederates employed canister and case in their batteries to repulse them with heavy losses. Sherman then resumed his flanking movements and forced the Confederates to retire within the fortifications at Atlanta, Georgia. As Sherman advanced toward Atlanta, Hood, superseding Johnston, assaulted the Federals just south of Peachtree Creek. Thomas' army had been crossing Peachtree Creek at many points but, due to lack of bridges the Federal artillery had been concentrated along Peachtree Road. It was thus able to participate in this action, and was no small factor in the Confederate repulse. Sherman next moved to the east of Atlanta to cut the Georgia Railroad. Here the Confederates suddenly attacked an exposed flank, both front and rear. Difficulties of communication prevented the complete synchronization of these assaults. Stubborn fighting by the Federal and efficient use of artillery contributed materially to the Confederate failure in this engagement. Sherman, on the field of battle, personally directed the placing and firing of some guns which did particularly effective work. The Federals next shifted west of Atlanta to cut the Atlanta and West Point Railroad. Again the Confederates sought to assail an exposed flank, but found it too well protected for their comfort. Federal infantry threw back the assault, and it can be said that this is the only major engagement of the Atlanta campaign in which artillery did not play a conspicuous part. Sherman invested the city and on August 31 put in motion almost his entire army toward Jonesboro, a point on the Macon and Western Railroad, Hood's only line of supplies and communications. Here on September 1 Davis' Division of the 14th Army Corps attacked the Confederate position. Federal artillery supported the action and after the successful conclusion of the assault it was found that the artillery had damaged Confederate guns in place along this portion of the line. Throughout the Atlanta Campaign the Confederates, considerably out numbered, were on the defensive, and offered to fight only when the terrain gave them a definite advantage. Occupying ridges as they did, excellent positions for artillery were usually available, which provided visibility necessary for accuracy, and also made possible a plunging fire upon the Federals. The Confederates often placed their artillery on the main life of fortifications because their guns had a more limited range of fire and because they were forced, due to lack of rifled guns and ammunition, to employ their artillery, not against the enemy artillery, but against the enemy troops themselves.

The Federal army, on the offensive, had to advance and envelop the entrenched Confederate positions, placing their artillery on less favorable ground. The superiority of their guns, both numerically and as to range, counterbalanced the Confederate advantage of position. Furthermore, the abundance of ammunition enabled them to employ this arm more freely. Federal artillery was used to push back the Confederate skirmish lines and to keep the Confederates closely within their fortifications. Enfilade fire was used successfully on salients in the Confederate lines and artillery barrages were employed to aid assaulting columns. During flanking operations Federal artillery was employed to hamper Confederate troop movements to meet the threat of the moving Federals. After the battle of Ezra Church 4-1/2-inch rifled guns were used for the bombardment of Atlanta. So accurate was the fire of these guns and so long their range that the inhabitants of the city were forced to flee their homes and live in cellars and in holes cut in railroad embankments. The artillery was particularly subject to the attention of sharpshooters. Barry reports that during the campaign three division chiefs were killed and the chief of artillery of the Army of Tennessee was wounded seriously while they were selecting suitable positions for their batteries.

Artillerymen of both armies, despite the rigors of campaigning, developed intense loyalty to their branch of the service. One instance which came to Sherman's personal observation is described in his Memoirs. He relates that during the battle of Atlanta DeGress' battery of 20-pounder Parrotts was captured and "Poor Captain DeGress came to me in tears, lamenting the loss of his favorite guns; when they were regained he had only a few men left, and not a single horse. He asked an order for a re-equipment, but I told him he must beg and borrow of others till he could restore his battery, now reduced to three guns. How he did so I do not know, but in a short time he did get horses, men, and finally another gun of the same special pattern, and served them with splendid effect till the very close of the war. This battery had also been with me from Shiloh till that time."3 This article deals primarily with the use of artillery during the Atlanta Campaign, but it must be remembered that no battle or campaign can be won except by the combined efforts of all arms and services. General Cox, commanding a division in Schofield's 23rd Army Corps, summarizes the campaign in the following manner: "Brothers of a common stock, of equal courage and tenacity, animated by convictions which they passionately held, they did on both sides all that it was possible for soldiers to do, fighting their way to a mutual respect which is the solid foundation for a renewal of more than the old regard and affection. "This union of courage, intelligence, and zeal was also the source of new expedients in warfare. The methods used at the close of the campaign were such as had been developed by the wonderful experiences of that summer's work. From general-in-chief to the men in the ranks, all were conscious of having learned much of the art and practice of warfare, and he would be a rash critic who would confidently affirm that he could find better means to attain desired ends than those which were employed in attack or defence over a hundred miles of mountains and forests in Northern Georgia."4 (1) The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, Series I, Vol. 38, Part 1, pp. 119-123. (2) Op. cit., series I, Vol. 38, part 3, p. 761. (3) Vol. II, 81 (4) Jacob Dolson Cox, Atlanta (Scribners', New York, 1882), 217. | ||||

| <<< Previous | > Contents < | Next >>> | ||

|

regional_review/vol4-6g.htm Date: 04-Jul-2002 | ||||