|

PARTNERSHIP AT JAMESTOWN

Archeology and History Work Hand in Hand

BY J. O. HARRJNGTON,

ASSOCIATE ARCHEOLOGIST,

COLONIAL NATIONAL HISTORICAL PARK, VIRGINIA.

One of the most universal characteristics of the

human race is an interest in the past. This is attested by the fact that

in the most primitive human groups myths and legends telling of the

origin of the earth and of the first human ancestors of the group exist

and are cherished from generation to generation. With the birth of

civilization, speculation gave way to study, and history was born---the

recounting of and explaining of the incidents in the life of a nation

and the world.

In recent years, as history has become studied

generally, people have taken an interest in the places associated with

the great men and events in the past of their nation. One important

outcome of this interest has been the establishment by the National Park

Service of the many historical parks and monuments. Jamestown Island,

the site of the first permanent English settlement in America, long has

been significant to Americans, and a part of it was logically acquired

and set aside by the Service for study, development, and

preservation.1 But at Jamestown it was obvious that the

conventional historical approach could not tell the entire story. Too

many of the records had been lost or destroyed; and too much of the

story never had been committed to writing in the first place. So a

different research method---archeology--- was called upon.

|

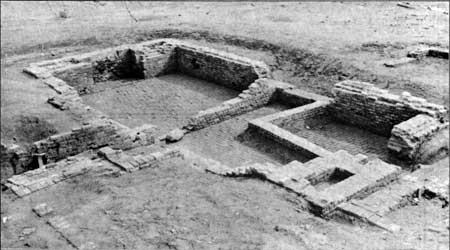

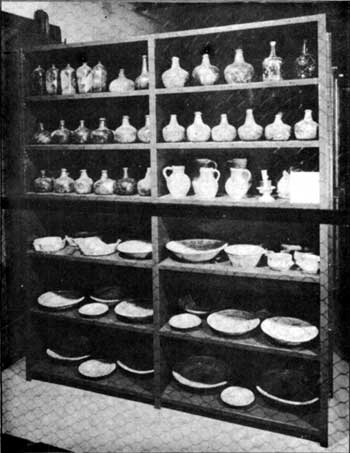

| Above is shown one of the many house

foundations which have been uncovered on Jamestown Island. Below: Some

of the glass bottles and pottery objects after their restoration in the

archeological laboratory.

|

|

Archeology is a relatively new science. Since the

beginning of the study of history, historians have run against an almost

impassable barrier, the barrier that stands where writing or recording

in some way first was developed. What had not been put on stone, clay,

papyrus, or paper could not be learned; and the early students of the

past could only guess at the meanings of the remains which we now know

to have been left by prehistoric peoples. But within the last 100 years

archeology has been pushing through that barrier. From soil strata and

potsherds, ruined buildings and cemeteries, archeologists have

reconstructed the story of the past so that today the school child who

begins the study of world history starts far back of the first written

records.

As archeology has developed it has shown that the

barrier of written records stands not only at a point in time, but also

at a point in culture. In other words, there has never been a time or

place when society had written down everything that happened to it. For

instance, Roman archeology has supplemented Roman history, not only in

the period before Romans started recording their history, but likewise

within the historic period, by supplying data concerning the development

of art and architecture and the details of domestic life of the time

which the Romans did not take the trouble to record.

In spite of the fact that history and archeology are

related so closely and are working to the same end, revealing and

explaining the facts of the past of the human race, they have not always

come together and applied their techniques consciously and

simultaneously to a specific problem. Within each field there is a

fairly well defined feeling that certain problems and periods belong to

the historian and certain others to the archeologist. At Jamestown,

however, the problem is being approached differently. Here historical

research and archeological research are working hand in hand to recover

the story of the years from 1607 to 1699, the period in which Jamestown

was the leading community of the colony of Virginia. The logic of the

program is readily apparent. Records of this first century of English

colonization of America are meagre when compared to those of later

periods. The early settlers were too busy wresting a living from the

wilderness to spend much time in recording their adventures for the

edification and entertainment of posterity. Of the records that were

made, only a part are available, many having been destroyed or lost.

Moreover, even as today, people seldom left permanent descriptions of

their houses, their furniture, and the dishes from which they ate. Many

of these missing facts now can be supplied by archeological

investigation.

Although the work is known as the Jamestown

archeological project and the problem is being approached primarily as

an archeological one, documentary research has an important place in the

program. A map, a deed, or possibly even a brief court record may be of

greater value in determining facts about a building than would a

season's excavating. The important thing is that the historian and the

archeologist are working together, planning their research with specific

problems in mind, and using the results of both kinds of research to

further the uncovering of the story. As each single tract or building is

considered for study, preliminary historical research is carried out as

the first step. These documentary data serve as a guide for directing

the course of the excavations and a key for interpreting the

archeological remains. As results accrue from the excavating, certain of

the documentary data take on new meanings which, in turn, provide more

intelligent direction for further archeological research. There is

accumulating, by this process, an ever-expanding body of knowledge made

possible by the combined activities of several fields of specialization.

This can be illustrated by a brief review of one fairly simple example

of research.

It long had been noted and had become a matter of

concern to persons interested in the preservation of historic sites that

Jamestown Island was being washed away rapidly by the waters of the

James River. Early in the present century, through the efforts of the

Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities, a substantial

shore protection was constructed at the upper end of the island by the

United States Army, and in recent years the National Park Service has

continued the sea wall along the entire limits of the old town. Numerous

historians have pondered over the amount of destruction that had taken

place. An old cypress tree, standing today some 260 feet from the shore,

marks the position of the shoreline at one period, but there has been no

documentary evidence which, alone, would locate exactly the extent of

the land during the seventeenth century.

For a number of reasons, and particularly to aid in

locating and identifying land features and early buildings, it is

important that the position of the seventeenth century shoreline be

known. Colonel Samuel H. Yonge estimated that at the western tip of the

island there had been a recession of 482 feet, based on an assumed

annual rate of two feet a year until 1860 and four feet a year

thereafter.2 Such an estimate, although later proved to be

accurate, was not satisfactory for the purpose of locating exactly the

property lines and other early remains. It was up to the archeologist to

try his hand.

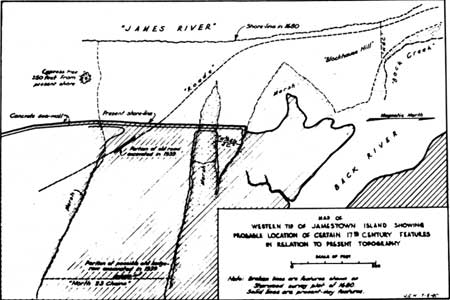

(click on image for an enlargement in a new window) Naturally there was no hope that any sort of evidence

could be found beyond the present shore because the currents and tides

would have destroyed or shifted even the most substantial remains. But

the archeological excavations made during the summer of 1939 did provide

evidence which permits the locating of a considerable portion of the old

shoreline. A patent to William Sherwood, dated April 20, 1681, reads in

part:

. . . beginning at James River at the head of a great

slash Issuing into the back River and down the sd slash East 1-2

a point Southerly Eighteene Chaines thence North 3/4 point Easterly

fower Chaines to the back River Marsh and up the same to a Markt

persimon tree under blockhouse hill point thence under the said Hill

West six Chaines to James River and downs it againe to the first

Mencon'd slash including eight acres & thence againe down the said

slash forty three Chaines to Mr Richard James Land and along it

South twenty three Chaines to a branch of Pitch & Tarr swamp thence

up the said branch to James River and Up the River to the place it

begun. . .3

This document, although of considerable value, would

have been of little help within itself unless certain of the landmarks

mentioned could be located and identified beyond question. Fortunately,

however, there is preserved among the Ambler Papers in the Library of

Congress a copy of a survey which Sherwood had made for this piece of

land.4 Shown on this survey plat is the old road leading from

Jamestown to the mainland. Also indicated are the adjacent marshes and

the shore of the river. It was found, by fitting this tract to the

present topography, that the marshes could be made to coincide with the

present ones, but corroborative evidence of a more specific character

was desired.

Exploratory trenches were excavated across this area

from the present shoreline to a distance well beyond the probable

eastern extent of the tract. In so doing, the remains of an old, much

used road were found. They were followed for 140 feet, a distance

sufficient to determine the direction. Then again placing the Sherwood

plat on the map of today, but making the roads coincide, it was found

that the east line of the property coincided exactly with an indistinct

line of dark areas which had been recorded as remains of trees or a

hedgerow. By locating the Sherwood tract to conform with the position of

the road and the property line, it was found that the outlines of the

marshes coincided almost exactly with those shown on the survey plat and

established that there has been little change in the topography of this

section of the island with exception of erosion by the river. The map

reproduced on the preceding page shows both the present-day topography,

including the road and property line found in the excavating, and the

features recorded on the survey plat; and there now can be located, with

considerable assurance, the position of the old shoreline for a distance

of more than 2,000 feet.5

This example serves to illustrate the manner in which

archeological and documentary research work together, each

supplementing, interpreting, and verifying the facts brought to light by

the other. Although many more instances could be cited, much less simple

than the one described here, the general problem and method of approach

have been indicated. By such research, under the combined studies of

historian, archeologist, museum specialist, and architect, considerable

knowledge has been gained concerning Jamestown during the seventeenth

century. The exact extent of the town has been determined, the location

of various tracts of land has been ascertained to with in a few feet,

and roads, fences, wells, bridges, orchards, ditches, and a large number

of buildings have been located and identified as to age and ownership.

Moreover, by combining the information from the excavating and from

documentary research, knowledge is accumulating as to the architecture

of the seventeenth century and the tools and objects in use by the

colonists during that period.

These results, valuable though they may be in the

future interpretative development of Jamestown, are possibly no more

important than the far-reaching effects of this relatively new approach

to the study of historic sites. The demonstration that a great quantity

of historical knowledge can be obtained by careful, painstaking

archeological research, no matter how recent the site, may be the most

significant contribution of the work at Jamestown.

1An important portion of the site of

Jamestown, which included the single standing seventeenth-century ruin,

the old brick church tower, was acquired in 1893 by the Association for

the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities. This organization, in keeping

with its policy of preserving significant historic sites, has developed

and safeguarded that part of the area with characteristic energy and

wisdom. The remainder was acquired by the United States government in

1934 as a unit of Colonial National Historical Park. The agreement just

made between the Association and the National Park service, concerning

cooperative investigation, development, and preservation of the

Jamestown treasures, is described on page 7.

2The Site of Old "James Towne"

1607-1698 (Richmond, 1926), 25-26.

3Ambler Papers, No. 31, Library of

Congress.

4Ibid., No. 134.

5The portion of the Sherwood survey plat

shown on page 4 was enlarged to exactly the same as that of the

present-day map.

Agreement Unifies Jamestown

Program

An outstanding example of the potentialities for

cooperation resulting from enactment of the Historic Sites Act of 1935

was the agreement reached September 20 between the Association for the

Preservation of Virginia Antiquities and the National Park Service. The

understanding, which was announced by Mrs. Arthur P. Wilmer, president

of the Virginia organization, provides for a unified program of

development and administration for the entire Jamestown Island area, a

part of which is in federal ownership while another portion, including

the sole remaining ruin, belongs to the Association.

The agreement, an outgrowth of some 18 months of

mutual study, also authorizes the Service to conduct archeological

investigations in selected sites; and it assigns, in any museum that the

Service may build, special galleries for the preservation and display of

Association-owned historical objects uncovered by the explorations.

"The agreement as to trenching the island will make

it possible to decide certain moot historical questions regarding which

historians have differed for many years," said Mrs. Wilmer. "The

location of many important sites on the island, where English

civilization was first planted on American soil, has been a subject of

controversy for some years, and archeological trenching will enable

historians to study the historic end of Jamestown Island, which the

Association owns."

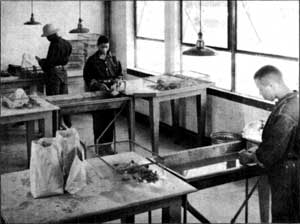

Civilian Conservation Corps Enrollees Washing and Sorting

Artifacts in the Jamestown Archeological Laboratory.

|

The A. P. V. A. acquired its preservation holdings at

Jamestown when the island faced destruction from the erosional action of

the James River. The Association's noteworthy program of conservation

and development was continued over a number of years and the need for

further exploration was recognized, but, explained Mrs. Wilmer, it

"would have been impossible for the A. P. V. A. with its small personnel

and limited capital, as would the erection of an adequate, fireproof

museum in which to house and display the interesting objects uncovered

by these investigations. Many important artifacts unquestionably will be

found on this end of the island, which has had virtually no

archeological investigations before this time."

The committee on cooperation with the National Park

Service, which studied the unified preservation and development program

for Jamestown, was composed of Miss Ellen Harvie Smith, chairman;

Herbert Claiborne, Granville G. Valentine, Miss Elizabeth Watkins, and

Mrs. Hampden Chamberlayne. Murray M. McGuire was legal adviser, and Dr.

Fiske Kimball, a member of the Service's Advisory Board on National

Parks, Historic Sites, Buildings, and Monuments, was designated general

adviser.

|