|

(click on image for an enlargement in a new window)

AMERICA'S STATE PARK AGENCIES

None Is Perfect, All Have Virtues

BY R. M. SCHENCK,

INSPECTOR.

To select, acquire, preserve and maintain areas of

natural features, scenic beauty, recreational utility and historical and

scientific interest, for the health, education, and pleasure of the

people -- these and similar objectives have led to the creation of state

park departments and the growth of state park systems. The growth has

been continuous because park and recreational areas are recognized as

indispensable to modern civilization.

Thirty-six of the present primary organizations

administering the various state park systems have been established since

1920, and 22 of that total have assumed their present form since 1930.

The beginning of the movement, however, goes back to 1865, after

Congress had granted to California the Yosemite Valley and the Mariposa

Grove of Big Trees for state park purposes. In the 1880's, New York,

Michigan, Minnesota and Connecticut established their first state parks.

Other states, notably Massachusetts, made important contributions to

early legislation.

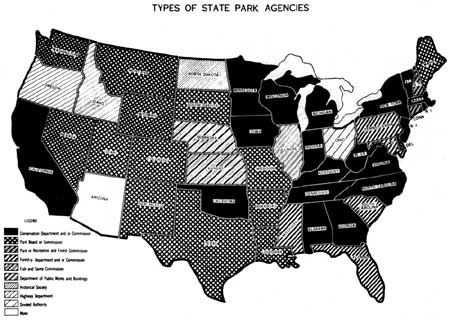

There was little coordination between states during

the establishment of the earlier state parks. For this, and perhaps

certain other reasons, their administrative structures differ widely. At

present there is considerable variety both in the types of

administrative authority charged with the responsibility for parks and

in the designations of such departments. This is illustrated by the

accompanying map with explanatory notes showing the various types of

organizations that have been developed. The most characteristic type of

unified administration in the eastern section of the country is the

conservation department or commission; west of the Mississippi the park

board or commission is predominant. A forest department or commission is

the primary agency for the administration of state parks in eight

states, while a department charged with dual responsibility for parks

and other aspects of conservation, such as forestry or game and fish,

has jurisdiction in four states. Other types of administrative authority

are the historical societies in North Dakota and Ohio, the highway

department in Oregon, the Departments of Public Works in Illinois and

Idaho, and the land commissioners in Montana. In some states there is no

recognized primary administrative authority, a condition which may be

illustrated by Ohio where the administration of lands used for park

purposes is divided among two or more agencies. Arizona is the only

state which has passed no general legislation in the interest of state

parks.

In view of the wide variety of park administrative

organizations and because, too, the successful administrative system

depends for its success as much on the type of men who compose it as on

the mechanics of organization, it is difficult to be specific as to the

best type of administrative system. As a matter of fact, there is no

best administrative set-up for state park systems. Certain advantages

and disadvantages may be observed in all of them.

For those states having no existing park

organization, an independent board or commission of five or six members,

appointed by the Governor and having staggered terms, may furnish the

best machinery for supervising parks and recreational matters. For

states where park work already has been properly recognized, a

conservation department or commission may be nearest the ideal. A

conservation department, park board, or commission, headed by a

nonpartisan board with staggered terms, may coordinate most effectively

the work of park and related agencies. The functions of such a board

should be (a) to establish policies, (b) to determine budgetary

requirements and major fiscal policies, and (c) to select the executive

head of the department, but not to participate in administrative

matters.

Probably it will not be possible to attain in the

near future any great similarity between state administrative

organizations, and this is perhaps not necessary; nevertheless, it is

certain that there are now too few good state systems of organization.

In general, each state should have its park and recreation

administration sufficiently well organized to take the lead whenever

possible in assisting the county, metropolitan, and other park districts

in recreational matters.

While there is considerable variation in the scope of

authority granted to park administrators, commissions, or boards,

certain powers are found to be common to most. They usually are

authorized

(a) to acquire lands by gift, purchase (including

condemnation), or otherwise for state park and recreational purposes and

to develop such properties for the purpose for which they are

established,

(b) to reject lands, whether donated, devised or

bequeathed, for inclusion in the state's park system,

(c) to establish lands already in state ownership as

parks or recreational preserves,

(d) to construct necessary roads, structures, and

other facilities in the parks,

(e) to employ technical and administrative assistance

as may be required properly to operate, plan, study, or survey the

state's recreational facilities or the need therefor,

(f) to expend such funds as may be available for

personnel and other necessary expense of operation,

(g) to make and enforce regulations relating to the

care, protection, and use of areas,

(h) to impose such fees as may be considered

reasonable and proper for the use of facilities and

(i) to contract with private persons for operation of

services.

There can be no doubt that the features (a) to (g)

inclusive are necessary and desirable for the proper administration of

parks. It may be well, however, to obtain authority by basic legislation

for imposing fees for use of facilities because there are strong

arguments against any such charges. Some insist that a charge should be

made as much for the psychological effect of inducing appreciation on

the part of visitors as for aiding in furnishing funds for maintenance.

In any case, the question of fees is for the several states to

determine. Where the federal government participates in construction the

chief interest of the National Park Service, so far as state fiscal

affairs are concerned, is to see that funds are forthcoming from some

source to provide for operation and maintenance of facilities

constructed in state parks with federal funds.

In like manner, the problem of concessions is for the

states to solve. Some believe that the licensing of conditional

concessions is the practical method of meeting the special accommodation

problem if authority be reserved to the state to regulate both

accommodations and prices. It has been the general experience in both

the federal and state park areas that exclusive concessions with

government control of prices is preferable to competition as a means of

assuring that services will be provided to the public at reasonable

prices. State operation of services has been undertaken in a few

states.

Most state-administered properties established

primarily for recreation are called state parks. The term may be said to

have a slightly different meaning in various states. Certain states have

established definite and high standards for their parks while others

include park properties which are almost wholly local in appeal. It is

therefore important that the park administrator classify his

recreational holdings and administer them in accordance with their value

and use. It may be well to include here a brief statement regarding the

history and classification of holdings.

It has been nearly 75 years since the first state

park was established in California. Later this park was turned over to

the federal government and is now our world-famous Yosemite National

Park. One of our greatest natural wonders, Niagara Falls, inspired state

officials in 1885 to dedicate the Niagara State Reservation as New

York's first state park. During that same year Mackinac Island and Fort

Michilimackinac, originally military reservations, were transferred to

the state of Michigan by the federal government for park purposes.

Itasca State Park, Minnesota, containing beautiful lakes and valuable

forests, was created in 1891. The Israel Putnam Memorial Camp Grounds,

Connecticut, of historical interest, was established in 1887. The first

state park areas, therefore, contained superlative scenery or were of

historical interest.

As the states recognized their responsibility for

providing for recreational needs many more areas were acquired and it

was difficult to formulate a definition of a state park. There was once

a popular belief that there should be "a state park every 100 miles."

During the last 20 years many areas have been acquired primarily to

satisfy the need for healthful and educational recreation. Some parks

therefore were established which appeared to be of questionable quality.

Yet, to criticize states which recognized the need of facilities for

recreation as a legitimate function of state government with no one

measuring rod for selecting, acquiring, and preserving state areas,

would be folly. Those states which pioneered in the state park movement

deserve the utmost credit. As automobiles became numerous and sufficient

good roads were built to permit ready access to areas some distance from

centers of population the need for more areas and adequate recreational

facilities became more apparent. Acquisition of large holdings was not

always practicable or possible. Lack of funds, availability of suitable

areas, cost of land, public support, the need for recreational areas

near centers of population not otherwise provided, and other factors

frequently dictated the policy of selecting park areas.

As a means of assuring good administrative practice

with respect to each classification or type, and in order that the using

public may have a reasonably definite concept of the character of the

various types, it would appear desirable for the several agencies

entrusted with administration of recreational areas to give serious

consideration to a common classification based on a standardized

terminology. Proper classification would aid materially in planning and

development of policy, obtaining funds for development, encouraging

local and federal participation or assistance, and simplifying the

directing of interstate travel.

The actual form that the organization for

administration may take depends upon the degree of centralization

desired and upon whether the park system is new or firmly established

within the state. The number of persons needed in the organization

depends on the size of the system, its previous ability to obtain

results, public support, available information, and the amount of

assistance obtainable from other departments or agencies. A well

established state park organization perhaps will include:

1. A park administrator or executive.

2. A division of planning which would function

frequently in advance of land purchase to determine need and priority of

areas and facilities to be developed, to prepare necessary landscape,

architectural, and engineering plans, and to assist in the problems of

maintenance.

3. A division of recreation, headed by a recreational

supervisor, to advise and plan for the recreational use of all areas of

the system.

4. A division of operations performing the functions

of budgeting, accounting, and procurement.

5. A public relations division to acquaint the public

with the services available, and to train personnel.

Regardless of the number of persons employed or of

how their functions are combined, those functions may be expected to be

present and, while they are of unequal importance, the neglect of any of

them will have a profound effect on the service rendered to the public.

Too often the function omitted is that of the recreational planner. He

can be all-important in promoting the wisest use of areas by utilization

of the most effective educational methods, by creating enthusiasm in

communities, and by enlisting volunteer leadership which may assure

public support.

Notwithstanding the importance of the central

administrative agency, the success of a state park and recreational

organization will depend on the success of its individual areas. In

those areas the greatest stress must be placed on the selection and

training of personnel, for the park superintendent or manager is the key

to success. The park that he administers is a recreational resource, and

how successfully this resource fulfills its function will depend on his

ability to understand and interpret intelligently its latent

possibilities to the people. The successful superintendent will

capitalize on opportunities to carry out the broad program of his park

and at the same time to enlist that public support which is needed for a

public function.

Increasing appreciation of scientific planning is one

of the most encouraging trends of our time. Initiation, planning,

design, and construction invariably should originate with and be carried

on under the direction of a competent division of planning or a planning

consultant. The technician has a scientific reason for what he designs,

builds, or wants done, and if he is a good technician his reason is

usually a sound one compatible with the purpose and proper use of the

area. The park administrator has the job of correlating these ideas and

efforts into a workable general scheme. That must be done with a

sympathetic understanding of the problems and the public needs. It is

easy, of course, to be led far afield in planning; and there also is

danger in considering minor technical problems too seriously, just as

there is danger in yielding too rapidly to the constant demands of the

general public. Good "horse sense" is still necessary for planning and

administration even in these horseless buggy days. When considering just

how much and what type of use the individual area will permit and the

number of facilities to be provided for, it is well to recall the

statement made by Harold S. Wagner, president of the National Conference

on State Parks:

The fact is that any given park areas has a given

capacity for people before a stone is turned. Upon completion of

development, too, each area has a limited ability to provide for human

use.

Structures and facilities must be sturdy and

fool-proof if maintenance costs are to be kept within reason. Visitors

are inclined to trample, disfigure, and destroy things which are ugly

and inadequate. Well designed structures and good materials adapted to

their use should be subordinated properly to their surroundings by

location and planting. One of the factors materially affecting the costs

of upkeep and operation is the building of "perception" in the minds of

the general public. It may be built or stimulated by signs, arrests,

exhibits, trails, publicity, and in many other ways.

Those who have observed the trend of recreational

development during the last several years have not failed to note the

numerous opportunities for better planning, development, and

administration of state parks. Altogether, in the big program which lies

ahead, a two-fold ambition will remain the goal of planner, developer,

and administrator: that of assuring a maximum of human use and benefit,

and a minimum of impairment of park resources.

|