PALISADED

TOWN

BY CHARLES H. FAIRBANKS,

JUNIOR ARCHAEOLOGIST,

OCMULGEE NATIONAL

MONUMENT, GEORGIA.

|

|

Four hundred years ago the wooded valley of a winding

stream, now called the Ocmulgee River, echoed the tread of warhorse and

soldier and the dull crack of the arquebus. These discordant sounds

belonged not to the native Indian but signaled the advance of Hernando

de Soto and his soldiers in search of a new land filled with glory and

gold. The Spaniards never reached the Old Ocmulgee Fields which now

comprise Ocmulgee National Monument. They did, however, visit Indian

towns a few days' journey down-river, thus giving the modern student his

first written record of that past. These Indians we now call Lamar,

because the plantation of that name was one of their principal villages.

They spoke the Muskogean language and had but recently come into central

Georgia conquering and driving out the earlier tribes. Their conquest

was not an easy one, however, and we find that their larger towns were

carefully defended against attack. These defenses have recently been

explored at the Lamar tract and it is now possible to draw an accurate

picture of them.

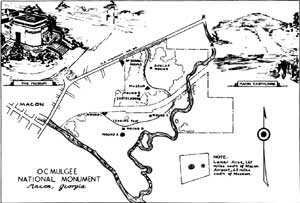

(click on map for an enlargement in a new window)

|

The Lamar Indians first chose, as the site for their

village, a secluded spot in the Ocmulgee valley. The river valley was

much wetter than now. The Ocmulgee River has deposited two or three feet

of silt in this region since the forests were cut, thus raising the

level of the entire area. The place the Indians picked was a hammock of

higher ground in the swamp. This siland or knob, itself fairly dry, was

completely surrounded by sloughs and dank bogs. Travel through these

swamps today is extremely difficult, except during dry weather. Four

hundred years ago travel must have been almost impossible.

At the present the swamps are inhabited by a large

and bloodthirsty tribe of mosquitoes. They certainly did not make the

Lamar village a pleasant place to live. The Indian, with a protective

coat of grease, probably got along with a minimum of slapping and

scratching. His practice of keeping the household fire burning from one

New Year's Dance to the next may have helped to drive off mosquitoes and

gnats.

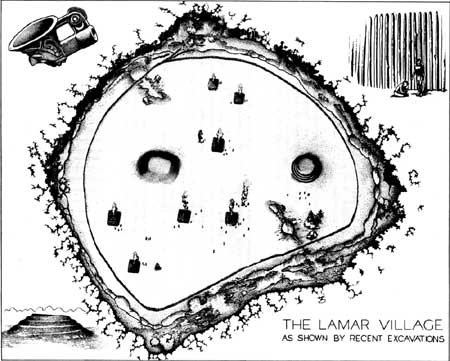

In addition to the encircling swamps the town was

provided with a man-made defense. This consisted of a palisade and ditch

completely surrounding the village. The first drawing shows a modern

artist's conception of this town. The palisade was arranged in a half

circle around the two mounds and the residences of the village. It

completely enclosed an area of about 25 acres. This semicircular form

was necessary because of the shape of the "island" on which it was

built. Their first palisade enclosed a comparatively small area which

soon proved too restricted for the village. Then the second line was

built which enclosed nearly all of the available land higher than the

swamp.

To modern soldiers the palisade would not appear to

be of much value in defense. It was made of logs about eight inches

thick and twelve to fifteen feet long. These were firmly set in the

tough red clay to a depth of about 18 inches, the posts were placed

about one foot apart, this resulting in an open or "picket" type of

fence about 12 feet high. This palisade was not a curtain or screen to

stop arrows, but an obstacle to stop the charging enemy. Outside the

stockade was a large open ditch which followed the edge of the island

and connected with the swamps. This ditch, partly filled with water and

muck, was an additional barricade. Georgia red clay, when wet, is a good

obstruction. On some sides, perhaps were attacks had occurred

frequently, extra lines of posts were put up to reinforce or screen the

main line. Entrances were likewise protected by an outer line of posts,

as the Indian had no use for a gate in such a palisade. He constructed

the entrance by curving one line outside the other. One early writer

described this as resembling the coil of a snail shell. It is probable

that small watch towers guarded the entrance. Only one entrance, on the

north side, has been found at the Lamar Site. There the outer line of

posts forming the entrance disappears into the swamp muck. It is

possible that this indicates that travel through the swamps was by

canoe. That would seem to be the most pleasant way to travel but we do

not know exactly how much water there was in the swamps at that

time.

(click on image for an enlargement in a new window)

At the northwest side of the palisaded town there

were two large pits, each more than fifty feet in diameter and at least

five feet deep. One lay outside the palisade, the other inside. These

pits were kept partly filled with water as the bluish muck in the

bottoms clearly shows. Also there was an additional pair of pits at the

southeast side. The simplest explanation for these pits is that they

were water reservoirs for use during attack. This may well have been

their original use, but one of De Soto's soldiers says that such pits

were fish ponds. Fish in large numbers were caught in the spring by

various methods. A favorite method was to stun the fish with a poison

made from the roots of the Dwark Buckeye. Those fish not immediately

eaten were placed in the fish ponds to be used when needed. Many kinds

of fish found in the region will live for long periods in such small

ponds. The Lamar Indians were not very particular about the sanitation

of their ponds as large quantities of refuse were found in the pits.

From digging, the archaeologist is able to

reconstruct a picture of life in the past. We see a central town of fair

size with two temple mounds and many residences. It was built on an

"island" of higher ground surrounded by miasmic swamps. Insufficient

natural protection caused, or led, the Indians to build a palisade with

a maze-like entrance. Outside of that a ditch, partly filled with water,

connected with the deep swamps. As the village grew in size the palisade

was placed farther out till it bordered the swamp. Convenient ponds were

provided for the storage of water and fish. The field, of corn, beans,

and squash occupied nearby hammocks in the swamp. Travel may have, been

by canoe or by foot, following the winding trails through the bogs. Such

a place to live could not have been chosen because it was attractive and

must have been dictated by military necessity.

It was during this period that the Muskogean invaders

of Georgia developed their native empire that eventually became the

Creek Confederacy led by Emperor Brims. They were not purely defensive,

however, as they successfully conquered and absorbed many of the earlier

tribes.

The Indian method of fighting was based on small

parties, surprise and short hand-to-hand combat. The swamps, with the

ditch and palisade, prevented real surprises. The palisade, while

allowing entrance for daily purposes, gave the defenders some advantage.

Close combat usually goes to the party with some defenses, however poor.

The palisade probably gave the Lamar people a real sense of security but

certainly did not lull them into a false sense of safety.

While the archaeologist can deduce all these things

from holes in the ground and from differences in the color of the soil,

he must depend on written records to breathe life into his pictures.

These written records do not come from the Indian but from early

travelers in the South. As mentioned earlier, we have the soldiers of De

Soto to thank for one description of the Indian towns and fish ponds.

Other writers, soldiers, botanists, and missionaries left descriptions

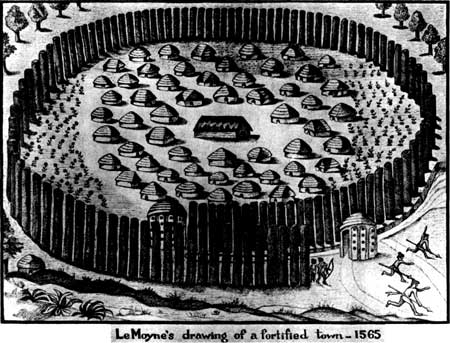

of Indian towns, but one man especially helps us. That was the

Frenchman, Jacques le Moyne, a painter of considerable skill, who

accompanied the expedition of Laudonnier to the Georgia and Florida

Coasts in 1565. This party was to reinforce the Huguenot settlements

already threatened by the Spanish. Le Moyne was supposed to map the

rivers and paint whatever there was of interest. He was inclined to

exaggerate the size of alligators and other strange animals but his

drawings show a real ability and a keen perception. The French were

disastrously defeated by the Spanish from St. Augustine but le Moyne

escaped and returned to France. His paintings were not published until

after his death when de Bry issued them, with a Latin text, at Frankfort

en-Maine in 1591. As they were drawn in 1565 they represent the coasts

of Georgia and Florida during the period of the Lamar Indians.

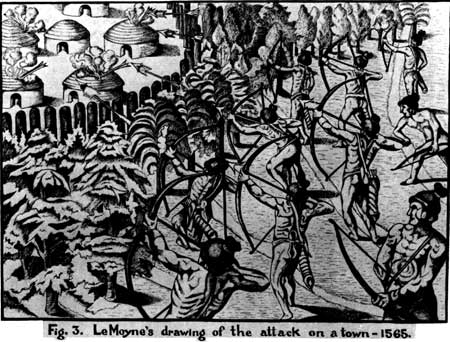

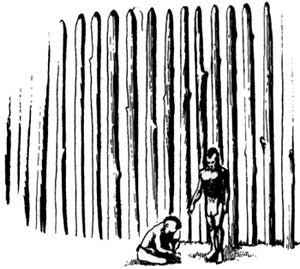

The first picture shows a fortified village of the

period. Le Moyne gave us the following description of their

fortifications.

"The Indians are accustomed to build their towns in

this manner. Some place is chosen near which a swift stream flows. They

level the place as much as they are able. Then they dig a furrow laid

out in a circle. Thick round poles of twice a man's height are placed

close together around the town (in this furrow) which is carried past

the entrance like a snail shell (spiral) so that a narrow entrance is

formed. No more than two abreast or together could be admitted. The

channel of the stream is also lead to this entrance. To each entrance

head it is the custom to erect a small round building, each one full of

loop-holes and slots. These houses are well made, considering their

means. In these are stationed as sentinels men who can detect the enemy

a long ways off; and who, as soon as they discover the enemy pursue them

and raise a loud cry, which is heard by the inhabitants of the town.

These rush to the defense armed with bows, arrows and clubs. In the

center of the town they place the kings house, sunk a little below

ground to avoid the sun's mid day rays. Circling this the houses of the

nobles."

This is a free translation of the Latin text of the

original and fairly well describes the type of fortified town found at

Lamar. Those coastal Indians had no mounds but the ditch and palisade

were described. They were probably closely related to the Indians of

central Georgia and le Moyne's drawing reveals to us a great deal about

the remains we have uncovered.

The second Le Moyne drawing shown illustrates an

attack on a palisaded town. Arrows with burning Spanish moss attached

are being used to fire the dry thatch of the houses. Little actual

combat is shown and the Frenchmen were surprised at the brevity of

Indian battles. In connection with this sketch it is interesting that

several burned houses were found at Lamar. The attack was only partly

successful and a later picture shows some houses still burning while the

Indians sadly bury their chief with appropriate ceremonies.

The Lamar site is being systematically excavated. In

the future it will be possible to restore the palisade and the houses.

In that restoration the work of the archaeologist and the early painter

Jacques le Moyne will be combined to recreate the village of an Indian

tribe who lived on the banks of the Ocmulgee when De Soto invaded

Georgia four hundred years ago.

|