|

MUSEUMS

where ———

when ——— why ———

BY NED BURNS,

CHIEF, MUSEUM DIVISION

The question of central museums to serve a group of

nearby monuments cannot be answered with a simple yes or no. The fear of

some that our museum program is in danger of overdevelopment is hardly

warranted, since our great problem is one of underdevelopment. All our

interpretive facilities still have a long way to go before they can be

considered adequate. Possibly some of this misapprehension arises from a

lack of understanding of the underlying principles of our interpretive

program. Many people confine their ideas of museums to a building

containing cases filled with relics and curiosities which does apply to

a number of poorly arranged museums in towns and cities, but this

conception of our park museums is not correct.

The proper approach to a correct understanding should

start with the realization that our two fundamental objectives are to

preserve and interpret our areas. Little need be said about the obvious

need for preservation. A service program of this type is not confined to

outdoor formations and structures. Many small objects which are an

integral part of the park or monument cannot be protected in situ so

they must be placed in a building equipped for that purpose. In

principle this is no different from constructing a protective shelter

over a large object in place out-of-doors.

Interpretation of an area may require a large museum

building or a series of buildings for its proper function. The use of

these buildings by the public is not necessarily confined to viewing

exhibits. They usually contain libraries, lecture halls, research and

administration quarters and other facilities. On the other hand some

areas may not need a museum building, since a few trailside exhibits and

labels may suffice. The extent of development in each park and monument

can be determined only by the particular interpretive needs of that

area. No arbitrary rule can be laid down for "a museum in every park or

every other monument" any more than the number of administrative

facilities or miles of road required for each particular park can be

fixed.

Jamestown Archaeological Laboratory and Museum

ILLEGAL MUSEUM PIECE (?)

The following was an AP story from London,

Kentucky: "State patrolmen, deputy sheriffs and a Federal deputy

captured a still in Levi Jackson Wilderness Road State Park. After the

'capture' they learned the still was 'a museum piece' being restored 'in

natural setting' to add to the park's display of 'former mountain

industries.'"

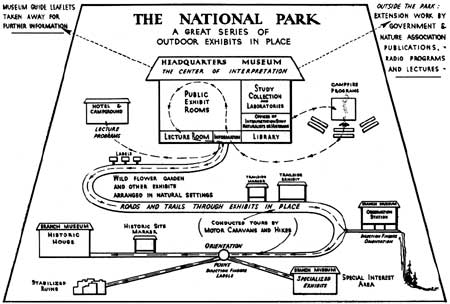

We regard the park itself as the exhibit and the

museum building only as a functioning interpretive device for a better

understanding of this outdoor exhibit. The important thing is to

interpret the area on the spot through whatever means is indicated by a

careful analysis of the individual needs of the monument or park. Guided

trips, campfire programs, descriptive literature, lectures with slides

and motion pictures have their useful functions but do not always

suffice. When they are combined with the visual aid of exhibits and

interpretive devices in doors or along the trails the sum total is

effective.

In a few instances central museums serving several

nearby areas which have the same general character and are approached

from one common center may be effective. Central museums to house large

collections of excavated or other materials from several related areas

for study, such as Ocmulgee, have also proved to be desirable and

effective. However, the separate needs for preservation and

interpretation should not be confused even though they sometimes serve a

double purpose as exhibits while being protected.

The use of graphic devices in close proximity to the

natural and historic features of the park is essential to good

interpretation. The National Park Service has a unique opportunity in

this field. We place graphic devices inside buildings as smatter of

convenience or necessity. The trailside exhibits, orientation maps,

signs and markers out-of-doors are an integral part of the interpretive

system. Whether the buildings, are large or small, one or many, is

merely incidental.

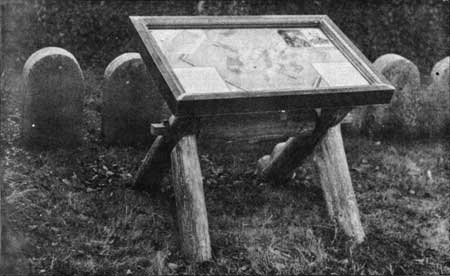

Historical exhibit at Stones River National Military Park, Tennessee

It frequently happens that outstanding examples of

geological, archeological, and historical interest occur together or are

in close proximity to each other in several small monuments or one large

park. In determining whether or not to employ one central museum with

several rooms, each devoted to a separate subject or to establish

several small one-theme museums, consideration should be given the

interpretive requirements of each feature rather than attempt a solution

by geography a lone.

We recognize and are working toward a better

coordination between related areas. Undesirable repetition should be

avoided in our parks and monuments, but in eliminating this recurrence

we must not forget the one time and first-time visitor. Occasionally

repetition may bore a few "chain visitors" but should not if the great

majority are first timers. We should always strive first to meet the

needs of the great majority, and, second, to provide for the

requirements of those special classes who are in the minority.

There is need for a closer integration of stories in

all our parks and monuments and also with related areas under other

federal, state or private control. Visitors want to know about the

history and scenic features of the country they are visiting and have

little interest in fine distinctions of jurisdiction. In telling the

story of military campaigns, routes of migration, ancient buildings, or

geological formations an introductory background must be supplied by

reference to other related areas regardless of their ownership. The

fault is not to be found in the principle of repetition itself, but with

the method by which it is done. The same story can be told in many ways

with emphasis on a new and interesting angle each time. Occasionally a

visitor may grow tired of hearing a replica if exactly the same story in

almost the same words on dendrochronology or pottery types after

visiting the third or fourth archaeological monument. The trouble lies

not with the subject, but with the stories themselves which can be made

dramatic and interesting by a varied presentation for the benefit of the

repeater as well as the first timer.

(click on the image for an enlargement in a new window)

We are still a long way from overdevelopment, but

while we are trying to build up properly, sight will not be lost of the

important need for proper integration on a national rather than a local

scale. This calls for comprehensive planning which must be based on a

thorough study of, first, what each area contains; second, its place in

relation to other areas; and third, a study of the visitors who come to

see it. The number and type of visitors, what their principal interests

are, from where they come, how long they stay and where they are going

after they leave, are important determining factors in developing a

suitable program.

Obviously the tempo as well as the type must be

carefully determined. A different approach can be used in the park where

the visitor stays overnight or for several days. The same person, when

at leisure in the evening with all arrangements for lodging and food

completed, is in a receptive mood different from that when he is

traveling in great haste along the highway trying to keep to a schedule

and allowing only a few minutes to see some interesting sight along the

way. Many factors outside the park and beyond our control shape

different attitudes in the same individual. A previous knowledge of the

park obtained from friends or through publicity channels causes a

different reaction from the accidental discovery of an interesting site

enroute. There is always a distinct reaction to the general attitude and

behavior of other visitors and the "atmosphere" of the place which may

provoke awe and reverence on the one hand or boisterous amusement on the

other. The actions of the same man at a picnic is in contrast with his

changed attitude while at tending a religious ceremony or a patriotic

meeting.

Carefully planned presentation, good showmanship in

its highest sense, is of paramount importance and should be consciously

employed in conjunction with a knowledge of the unique and basic facts

concerning each area. The whole consists of each of its parts and the

success of our entire interpretive system will depend upon the

individual success achieved in each park or monument. Sound policies

have been laid down and their successful application depends on a full

knowledge of the local needs and conditions in and surrounding each of

our areas.

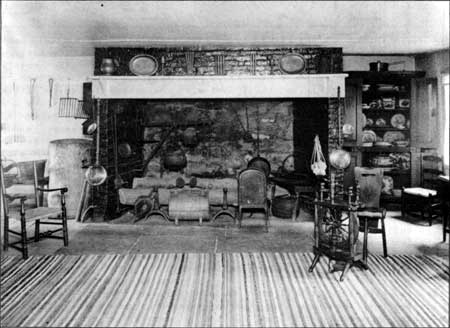

Kitchen at Washington's Headquarters, Morristown

National Historical Park

|