|

ACADIA

Circular of General Information 1936 |

|

ACADIA National Park

• OPEN ALL YEAR •

OUR national parks are areas of superlative scenery which are set apart and maintained by the Federal Government for the use and enjoyment of the people. They are the people's property; the Government, the people's agent and trustee.

Few in number, but covering an extraordinary range of landscape interest, they have all, with few exceptions, been formed by setting aside for park purposes lands already held in ownership by the United States and lie in the nationally younger regions of the country to the westward of the Mississippi.

The first exception is Acadia National Park, occupying old French territory on the coast of Maine and created in 1919 from lands collected during the previous decade and presented to the Government. The name it bears commemorates the ancient French possession of the land and the part it had in the long contest to control the destinies and development of North America. The park is unique as a member of the national system in its contact with the ocean and inclusion of nationally owned coastal waters in its recreational territory.

Acadia National Park lies surrounded by the sea, occupying as its nucleus and central feature the bold range of the Mount Desert Mountains, whose ancient uplift, worn by immeasurable time and recent ice erosion, remains to form the largest rock-built island on our Atlantic coast; "l'Isle des Monts deserts", as Champlain named it, with the keen descriptive sense of the early French explorers.

The coast of Maine, like every other boldly beautiful coast region in the world whose origin is nonvolcanic, has been formed by the flooding of an old and water-worn land surface, which has turned its heights into islands and headlands, its stream courses into arms and reaches of the sea, its broader valleys into bays and gulfs. The Gulf of Maine itself is such an ancient valley, the deep-cut outlet of whose gathered waters may still be traced by soundings between Georges Bank and Nova Scotia, and whose broken and strangely indented coast, 2,500 miles in length from Portland to St. Croix—a straight-line distance of less than 200 miles—is simply an ocean-drawn contour line marked on its once bordering upland.

At the center of this coast, the most beautiful in eastern North America, there stretches an archipelago of islands and island-sheltered waterways and lakelike bays—a wonderful region—and at its northern end, dominating the whole with its mountainous uplift, lies Mount Desert Island, whereon the national park is located.

Ultimately it is intended that the park shall be extended to other islands in this archipelago and points upon the coast, and become, utilizing these landlocked ocean waters with their limitless recreational opportunities, no less a marine park than a land park, exhibiting the beauty and the freedom of the sea. Without such contact with it and the joys of boating the national park system would not be complete.

THE STORY OF MOUNT DESERT ISLAND

Mount Desert Island was discovered by Champlain in September 1604, 16 years and over before the coming of the Pilgrim Fathers to Cape Cod. He had come out the previous spring with the Sieur de Monts, a Huguenot gentleman, a soldier, and the governor of a Huguenot city of refuge in southwestern France, to whom Henry IV—"le grand roi"—had intrusted, the December previous, establishment of the French dominion in America. De Monts' commission, couched in the redundant, stately language of that formal period, is still extant, and its opening words are worth recording, so intimate and close is the relation of the enterprise to New England history:

Henry, by the grace of God, King of France and Navarre, to our dear and well-beloved friend the Sieur de Monts, gentleman in ordinary to our chamber, greeting: As our greatest care and labor is and has ever been since our coming to this throne to maintain it and preserve it in its ancient greatness, dignity, and splendor, and to widen and extend its bounds as much as may legitimately be done, We having long had knowledge of the lands and territory called Acadia, and being moved above all by a single-minded purpose and firm resolution We have taken, with the aid and assistance of God, Author, Distributor, and Protector of all States and Kingdoms, to convert and instruct the people who inhabit this region, at present barbarous, without faith or religion or belief in God, and to lead them into Christianity and the knowledge and profession of our faith and religion. Having also long recognized from the accounts of captains of vessels, pilots, traders, and others who have frequented these lands, how fruitful and advantageous to us, our States, and subjects, might be the occupation and possession of them for the great and evident profit which might be drawn therefrom, We, in full confidence in your prudence and the knowledge and experience you have gained of the situation, character, and conditions of the aforesaid country of Acadia from the voyages and sojourns you have previously made in it and neighboring regions, and being assured that our plan and resolution being committed to your care you will diligently and attentively, and not less valorously and courageously, pursue them and lead them to completion, have expressly committed them to your charge and do constitute you by these presents, signed by our hand, our lieutenant general, to represent our Person in the lands and territory, the coasts and confines of Acadia, to commence at the fortieth degree of latitude and extend to the forty-sixth degree. And We order you throughout this territory as widely as possible to establish and make known our name and authority, subjecting to these and making obedient to them all the people dwelling therein, and by every lawful means to call them to the knowledge of God and the light of the Christian faith and religion.

De Monts, sailing in the spring of 1604, founded his first colony on an island in the tidal mouth of a river at the western entrance to the Bay of Fundy—"Baie Francoise" he named it, though the Portuguese name "Bahia Funda", Deep Bay, in the end prevailed—which two centuries later, in memory of it, was selected to be the commencement of our national boundary. While he was at work on this he sent Champlain in an open vessel with a dozen sailors to explore the western coast. A single, long day's sail with a favoring wind brought him at nightfall into Frenchman Bay, beneath the shadow of the Mount Desert Mountains, and his first landfall within our national bounds was made upon Mount Desert Island in the township of Bar Harbor.

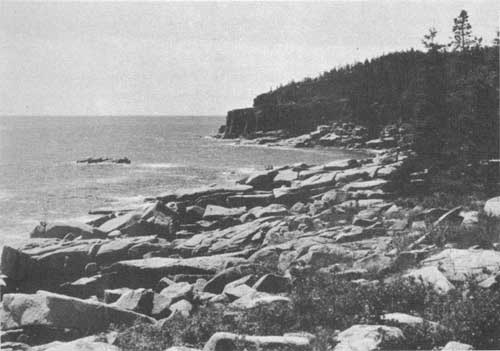

A bit of the rocky shore line. Rinehart photo.

A few years later the island again appears as the site of the first French missionary colony established in America, whose speedy wrecking by an armed vessel from Virginia was the first act of overt warfare in the long struggle between France and England for the control of North America.

In 1688, seventy-odd years later, private ownership began, the island being given as a feudal fief by Louis XIV to the Sieur de la Mothe Cadillac—later the founder of Detroit and Governor of Louisiana, who is recorded as then dwelling with his wife upon its eastern shore and who still signed himself in his later documents, in ancient feudal fashion, Seigneur des Monts deserts.

In 1713 Louis XIV, defeated on the battlefields of Europe, ceded Acadia—save only Cape Breton—to England, and Mount Desert Island, unclaimed by Cadillac, became the property of the English Crown. Warfare followed till the capture of Quebec in 1759, when settlement from the New England coasts began. To the Province of Massachusetts was granted that portion of Acadia which now forms part of Maine, extending to the Penobscot River and including Mount Desert Island, which it shortly thereafter gave "for distinguished services" to Sir Francis Bernard, its last English governor before the breaking of the revolutionary storm. Title to it was later confirmed to him by a grant from George III.

In September 1762 Gov. Bernard sailed from Fort William in Boston Harbor with a considerable retinue, to view his new possession and kept a journal that may still be seen. He anchored in the "great harbor of Mount Desert", just off the present town of Southwest Harbor, which he laid out with his surveyors; he explored the island, noting its fine timber, its water power for sawmills, its good harbors, its abundance of wild meadow grass "high as a man", and of "wild peas"—beach peas, perhaps—for fodder, and its wealth of fish in the sea. He had himself rowed up Somes Sound, a glacial fiord which deeply penetrates the island, cutting its mountain range in two. This he called the river, as in that region other inlets of the sea are called today, following the custom of the early French. And he visited Somes, one of the earliest settlers from the Massachusetts shore, then building his log cabin at the sound's head, where Somesville is today, and walked across to see a beaver's dam nearby, at whose "artificialness" he wondered.

Secluded woodland trail.

Then came the Revolution. Bernard's stately mansion on the shore of Jamaica Pond and his far-off island on the coast of Maine both were confiscated, he taking the King's side and sailing away from Boston Harbor while the bells were rung in jubilation. And Mount Desert Island, once the property of the Crown of France, once that of England, and twice granted privately, became again the property of Massachuestts. But after the war was over and Bernard had died in England, his son, John Bernard, petitioned to have his father's ownership of the island restored to him, claiming to have been loyal himself to the colony, and a one-half undivided interest in it was given him. Then, shortly after, came the granddaughter of Cadillac—Marie de Cadillac, as she signed herself—and her husband, French refugees of the period, bringing letters from Lafayette, and petitioned in turn the General Court of Massachusetts to grant them her grandfather's possession of the island—asking it not as legal right but on a ground of sentiment, the gratitude of the colonies to France for assistance given in their War of Independence. And the General Court, honoring their claim, gave them the other undivided half. Then it sent surveyors down and divided the island, giving the western portion, including the town of Southwest Harbor, his father had laid out, to John Bernard, who promptly sold it and went out to England and died governor of one of the West Indies, being also knighted; and the eastern half, where Cadillac once had lived and Bar Harbor, Seal Harbor, and Northeast Harbor are today, to Marie de Cadillac and her husband—M. and Mine. de Gregoire—who came to Hulls Cove, on Frenchman Bay, and lived and died there, selling, piece by piece, their lands to settlers. It is from these two grants made by the Commonwealth of Massachusetts to the granddaughter of Cadillac and the son of Bernard, each holding originally by a royal grant, that the Government's present title to its park lands springs. History is written into its deeds.

During the first half of the nineteenth century, Mount Desert Island still remained remote and inaccessible, except to coasting vessels, but fishing hamlets gradually sprang up along its shore, the giant pines whose slowly rotting stumps one comes upon today among the lesser trees were cut and shipped away, town government was established, roads of a rough sort were built, and the island connected with the mainland by a bridge and causeway. Then came steam, and all took on a different aspect. The Boston & Bangor Steamship Line was established; a local steamer connected Southwest Harbor with it through Eggemoggin Reach and Penobscot Bay, a sail of remarkable beauty; and summer life at Mount Desert began. The first account of it we have is contained in a delightful journal kept during a month's stay at Somesville in 1855 by Mr. Charles Tracy, of New York, the father of Mrs. J. Pierpont Morgan, Sr., who came with him as a girl, and which is still preserved. The party was large—26 in all—and filled Somes Tavern full to overflowing. In it, besides Mr. Tracy and his family, were the Rev. Dr. Stone, of Brookline, Mass., with his family; Frederick Church, the artist, and his sister; and Theodore Winthrop, killed afterward in the Civil War, who wrote John Brent, with its once famous description of a horse. They climbed the mountains, tramped through the woods, lost themselves at night—half a dozen of them—and slept by a camp fire in the wild; drove over to Bar Harbor, then on to Schooner Head, where they slept at the old farmhouse, climbing the then nameless "mountain with the cliff" that shadowed it at sundown, and drinking by the pitcherful such milk as New York could not supply, and then, like Hans Breitman, in climax to their stay they gave a party, importing by the boat to Southwest Harbor the first piano the island had ever seen and inviting to it the islanders and fisherfolk from far and near. It was a great success. They danced, they sang songs, they played games, and had a lobster salad such as only millionaires can have today, keeping up their gayety until 2 o'clock in the morning, when their last guests—two girls from Bar Harbor who had driven themselves over for it—hitched up their horse and left for home in spite of remonstrance and the offer of a bed. Such was the beginning of Mount Desert social life.

Surf on the rocks. Rinehart photo.

Ten years later, when the Civil War had swept over like a storm, summer life began in earnest at Bar Harbor, compelled by the sheer beauty of the spot. No steamer came to it till 1868; then, for another season, only once a week. No train came nearer than Bangor, 50 miles away, with a rough road between. But still it grew by leaps and bounds, overflowing the native cottages and fishermen's huts, sleeping in tents, feeding on fish and doughnuts, and the abundant lobster. The native cottages expanded and became hotels, simple, bare, and rough, but always full. The life was gay and free and wholly out-of-doors—boating, climbing, picnicking, buckboarding, and sitting on the rocks with a book or friend. All was open to wander over or picnic on; the summer visitor possessed the island. Then lands were bought, summer homes were made, and life of a new kind began.

It was from the impulse of that early summer life that the movement for public reservations and the national park arose, springing from memory of its pleasantness and the desire to preserve in largest measure possible the beauty and freedom of the island for the people's need in years to come. The park, as a park, is still in its beginning. It has now spread out beyond its island bounds and crossed the bay to include the noble headland and long surf-swept point of Schoodic, on the mainland shore. And Congress in giving the right to make the new extension changed its name from Lafayette to Acadia National Park, to tell of its region's early history and romance. Its lands have been, throughout, a gift to the Nation, coming from many sources, and much personal association is linked, closely and inseparably, with its formation. It is still growing, and with the contiguous land-locked ocean waters, beautiful as lakes and nationally owned like it, to extend out onto, there is no limit to the number to whom it may give rest and pleasure in the future, coming from our crowded eastern cities from which it is accessible by land or water, rail or motor car.

A WILDLIFE SANCTUARY

One important aspect of our national parks and monuments is that they—unlike the forests, devised to follow economic lines—are absolute sanctuaries, islands of shelter for the native life. Like the monasteries in the Middle Ages that sheltered—all too fragmentarily—the literature and learning of the classic period, they are a means of incalculable value for preserving in this destructive time the wealth of forms and species we have inherited from the past and have a duty to hand on undiminished to the future, so far as that be possible.

In this aspect of a wildlife sanctuary, plant and animal, Acadia National Park is remarkable. Land and sea, woodland, lake, and mountain—all are represented in it in wonderful concentration. In it, too, the Northern and Temperate Zone floras meet and overlap, and land climate meets sea climate each tempering the other. It lies directly in the coast migration route of birds, and exhibits at its fullest the Acadian Forest, made famous by Evangeline; and the northernmost extension of that great Appalachian forest which at the landing of De Monts stretched without a break from the St. Lawrence to the Gulf and is the oldest by the record of the rocks and richest in existing species of any mingled hardwood and coniferous forest in the Temperate Zone. And it possesses also a rich biologic field in the neighboring ocean, the parent habitat of life. Deeper waters apart, the sea beach and tidal pools alone form an infinite source of interest and study, while the ocean climate, like the land one, is profoundly different from that to the southward, off the Cape Cod shore.

Young bald eagles.

To take advantage of this opportunity an association has been formed, incorporated under the name of the Wild Gardens of Acadia, to cooperate with the Government in the development of the educational and scientific features of the park and its environment. By means of it a marine biological laboratory has been established on the shore, material has been gathered for a book upon the wild flowers of the park and wild gardens for their exhibition started, and entomological collections and studies in the bird life and geology of the region have been made. The park itself is a living natural-history museum, a geological and historic area lending itself remarkably to the nature guide and lecture service which is rapidly becoming so valuable a feature in our national parks.

Botanically, Acadia National Park forms an exceedingly interesting area. Champlain's term "deserts" in description of the mountains meant, in accordance with the original significance of the word, "wild and solitary"; not "devoid of vegetation." Vegetation, on the contrary, grows upon the island with exceptional vigor, and in wide range of form. The native forest must—before it was invaded by the ax— have been superb, and superb it will again become under the Government's protection. Wild flowers are abundant in their season, among them a number of species of conspicuous beauty, because of their loveliness in danger of extermination until the national park was formed and its lands became a sanctuary. The rocks, frost split and lichen-clad, with granite sands between, are of a character that makes the mountain tops, with their bearberries and blueberries and broad ocean outlook, wild rock gardens of inspiring beauty, while both mountain tops and woods are made accessible by over a hundred miles of trails built by successive generations of nature-loving summer visitors.

In addition to ocean, rocks, and mountain heights, to woods and wild flowers, and to trails trodden by the feet of generations, Acadia National Park has a rich possession in an inexhaustible spring—source of pure, delicious water rising—cool and constant—from beneath the mountain at the entrance from Bar Harbor, and made, with its free gift of water to the passing public, a memorial to the Sieur de Monts, the founder of Acadia.

View of rocks from Ocean Drive. Rinehart photo.

SCHOODIC POINT

Several years ago the bounds of Acadia National Park were extended to include Schoodic Point, enclosing the entrance to Frenchman Bay upon the eastern side as Mount Desert Island does upon the western. It was a splendid acquisition, obtained through generous gifts and made possible of acceptance by an act of Congress.

Schoodic Point juts further into the open sea than any other point of rock on our eastern coast. On it the waves break grandly as the ground swells come rolling in after a storm at sea. Back of the ultimate extension of the point a magnificent rock headland rises to over 400 feet in height, commanding an unbroken view eastward to the entrance of the Bay of Fundy, southward over the open ocean, and westward across the entrance of Frenchman Bay to the Mount Desert mountains in Acadia National Park. It is a view unsurpassed in beauty and interest on any seacoast in the world.

A park road branching from Maine's coastal highway to New Brunswick follows the rock-bound shore of Schoodic Peninsula to its surf-beaten extremity upon Moose Island, thence along the eastern shore of the Peninsula to Wonsqueak Harbor. There it connects again with the coastal highway, making a magnificent detour for motorists on their way to our national boundary and the Maritime Provinces of Canada.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

1936//sec2.htm

Last Updated: 20-Jun-2010