|

ANIAKCHAK

Beyond the Moon Crater Myth A New History of the Aniakchak Landscape A Historic Resource Study for Aniakchak National Monument and Preserve |

|

Moving Beyond the Moon Crater Myth

CHAPTER ONE

Father Hubbard's Geological Wonder World:

Perpetuating the "Moon Crater Myth" in Aniakchak National Monument and Preserve

Craters! Volcanoes! For twenty years I've been plumbing their depths in two hemispheres hoping I might come across one comparable in form, if not quite in size, to those vast craters we see on the moon.

Father Bernard Hubbard, "The Moon Craters of Alaska"

In the Saturday Evening Post article, "The Moon Craters of Alaska," author Barrett Willoughby recounts a tale of courage, endurance and adventure as told to her by famed Glacier Priest, Father Bernard Hubbard, S.J., when he and three strapping Santa Clara University football players explored the Aniakchak Caldera, a volcanic feature six miles wide, located on the "knuckle" of the remote, roadless and windswept Alaska Peninsula during the summer of 1930.

|

| Father Hubbard peers over some edge, perhaps into the caldera or from Black Nose, ca. 1930. Bernard Hubbard, S.J. Alaskan Photograph Collection. Photograph courtesy of Santa Clara University Archives. ACK-00-20. |

The article begins with Hubbard and his faithful crew descending into what they called a "weird world." There, the explorers endured a raging storm, stood on the edge of an active volcano, and even survived an encounter with a bear that looked "as big as an elephant." While trekking inside the Caldera on a rare sunny day, Hubbard and his crew scaled the flanks of Vent Mountain—"a volcano. . ." Hubbard later told Willoughby, ". . .growing inside a volcano!" From this central altitude, Hubbard could see the enormity of Aniakchak spreading below. "Standing in the sunshine on the brink of one mountain crater, we saw circling us the serrated edge of a larger crater that enclosed a potential national park, the like of which has never been known before." [1] Indeed, Hubbard was correct, for the crater was eventually designated Aniakchak National Monument and Preserve, one of the most isolated and least visited units in the national park system.

By 1930, adventure tales, especially those that took place in the Far North, were a dime a dozen, but Willoughby's "Moon Crater" article was more than a sensationalistic retelling of a geological conquest. Through Hubbard's vivid retelling of his expedition, the article established the Aniakchak Caldera as a unique, alien and lifeless world, void of human history. Almost immediately, Hubbard's interpretation of the "Moon Crater" evolved into a kind of ecological myth. Although cultural evidence on site proved otherwise, those resources for years were ignored. It was Hubbard's lens, not the eyes of those who actually lived in the area, through which the central portion of the Alaska Peninsula was viewed. This was especially true when the National Park Service proposed that it make Aniakchak a monument in 1931. The agency would later perpetuate Hubbard's Moon Crater myth as a way to describe the landscape of the central Alaska Peninsula for the next 50 years.

Making the Moon Crater Myth

The ground at which we stood was hot. The air was hot. Steam rose from the earth at our very feet. Strange sulfur odors filled the air. We were in a land of lifeless, ashen desolation—the land of the Thunder Mountains.

—Dick Douglas,

In the Land of Thunder Mountains

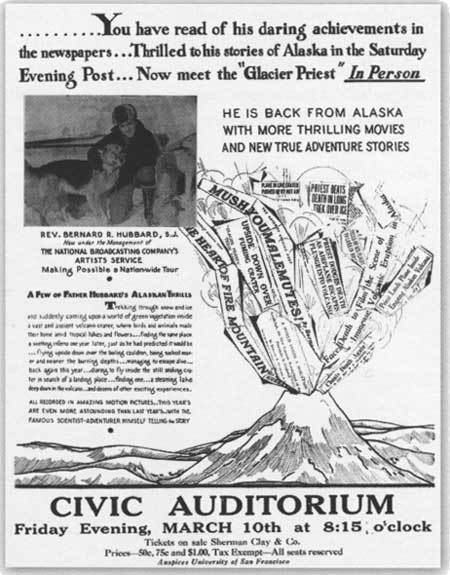

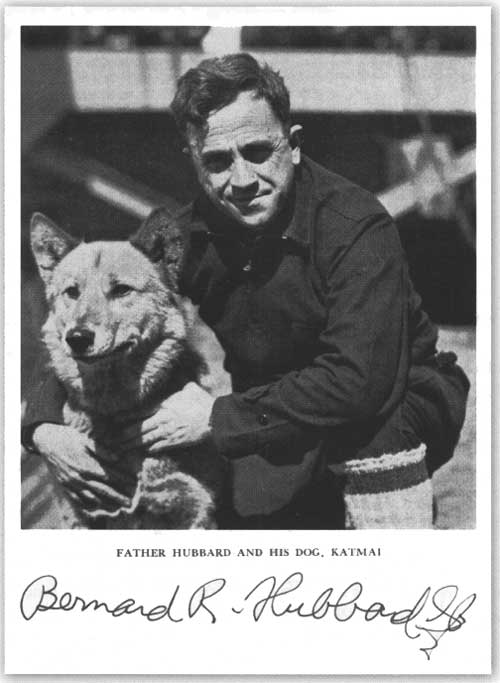

Father Bernard Hubbard was a professor of geology at Santa Clara University, who traveled to Alaska to document several adventurous expeditions to Aniakchak Caldera during the summers of 1930, 1931, and 1932. [2] Calling himself the "Glacier Priest," he reached an audience of thousands as a talented author, lecturer, photographer, and filmmaker. Those skills provided Hubbard with the unusual means to pursue a career as both a priest and adventurer. At a time when many Americans stood in soup lines, Hubbard succeeded on the lecture circuit mainly because he used his extraordinary talents to make Alaska, specifically Aniakchak, part of his "Glacier Priest" persona, using the natural wonder as a springboard to fame and as a setting for his own adventure drama. [3]

According to biographer Kathy Price, Hubbard skillfully melded his exploring experiences, publicity, and finished presentations into what she calls the "Hubbard mystique," a recognizable product that he could sell to raise funds to sponsor more expeditions to Alaska. [4] Not unlike polar explorers of an earlier century, Hubbard cultivated his so-called mystique by seeking what he considered sublime and exotic places to serve as exciting backdrops to his Glacier Priest persona. [5] From his promotions to his photographs and films, "Hubbard was not just the man behind the camera ..." observed Price, "... quite regularly, he was the man in front of it." [6] Thus, with the good luck of a timely eruption in 1931, and a public eager for stories of rugged adventure from the Last Frontier, Aniakchak Caldera served Hubbard's larger purpose.

Published in The Saturday Evening Post on December 13, 1930, the riveting "Moon Craters" article not only catapulted Father Hubbard into the national limelight, but captured the imagination of a Depression-struck country trying to do as Father Hubbard had done—endure all hardships and stare down fear, even if it meant taking one's chances inside an active volcano. Down-on-their-luck Americans were not the only readers intrigued by Hubbard's exploits in Aniakchak. The December issue had also reached Horace Albright, the Director of the National Park Service. Within a week after reading the article, the director sent a memorandum ordering his NPS staff to "make a special file of these "Moon Craters of Alaska"... "This is a very remarkable story that Father Hubbard tells in his article" noted Albright, "and I think we ought to keep these areas in mind as possible additions to the national parks or monuments some time in the future." [7] Enthusiastic about a new possible addition, one assistant saw no reason to wait. "Isn't now the time to get them reserved [as national monuments], to prevent hunting and thus to preserve the wonderful wild life as best we can?" [8]

|

| Aniakchak National Monument and Preserve is centrally located in the North Pacific. By B. Bundy. (click on image for a PDF version) |

In 1930, the National Park Service believed that its primary goal was to manage national parks as idyllic landscapes, highlighted by mountains, canyons, abundant wildlife, and fantastic natural phenomena. The purpose of such management was to celebrate America's geography of vast open spaces. This romantic nationalism towards public perceptions of the NPS perpetuated the notion that parks were virgin land. Such notions created what Richard West Sellars describes as a "From the New World" fantasy. [9] According to Sellars, this fantasy or illusion was driven by what he called "facade management," where park rangers protected and enhanced scenic nature while, at the same time, they ignored perceptions of the landscape held by Native American and other local residents. Likewise, Ted Catton argues in Inhabited Wilderness, that the NPS concept of nature during the 1930s was an intricate interplay of all living things in the absence of civilized human kind. [10] These early ideas of nature preservation served as the foundation to the Leopold Report, a threshold document that articulated NPS management of nature between 1963 and the early 1980s, and most certainly underscored the perpetuation of Hubbard's Moon Crater myth in later years on the central peninsula. [11]

|

| Lecture Flyer, ca. 1932. Courtesy of Kathy Price, Fairbanks, Alaska. |

In the context of façade management, the geological wonders of Hubbard's Alaskan moon crater seemed to fit the NPS criteria for a national park perfectly. For the "Moon Craters" article described the Aniakchak landscape as maintaining three distinct features: 1) it was unique or exotic, 2) mysterious, and 3) most significantly, void of human kind. To Hubbard, Aniakchak was "a region of Plutonic activity which for mystery, fascination, and weird beauty has no equal in any other part of the world." [12] The priest fondly called Aniakchak a "geological wonder world" and according to one of his films, it was "a place nobody knows." [13] Dick Douglas, who accompanied Hubbard into Aniakchak in 1931, described the region as "the land where storms are bred, a land of mysteries and dangers." [14] After spending many nights listening to the winds blow off the Bering Sea from inside his tent, Douglas could only borrow words from the poet Lord Alfred Tennyson to describe the lonely landscape:

A cry that shivered to the tingling stars,

And, as it were one voice, an agony

Of lamentation, like a wind, that shrills

All night in a waste land, where no one comes,

Or hath come, since the making of the world.

Apparently, the National Park Service agreed with Hubbard's claims. Aniakchak had potential to become a national park. When the volcano roared back to life in the spring of 1931, officials seemed even more intrigued about the events occurring on the remote Alaska Peninsula. That November, the agency invited Father Hubbard to give a lecture on the volcano at the Interior Department in Washington D.C. [15] Albright wanted to hear firsthand what the Glacier Priest had to say about Aniakchak.

Instead of discussing the Aniakchak region in terms of sound science, Hubbard, who never kept a journal and conducted very few field experiments, crafted his lectures based on a myth he invented to entice the media and entertain popular audiences. Rather than dismissing the Glacier Priest as sensationalistic and self-serving, the NPS adopted his vision of Aniakchak because, quite frankly, Hubbard's Moon Crater myth fit nicely with their own agenda—to preserve unique and fantastic natural features, which were presumably unaltered and untouched by man.

The Glacier Priest and the Last Frontier

When you've lived in the north, come in to find your camp torn up by bears and had to eat your dogs when you ran out of food, you don't mind a little thing like a lecture tour.

—Father Bernard Hubbard, the Glacier Priest

As one of "the highest paid lecturers in the world," Hubbard made a career crisscrossing the Lower 48, spell-binding audiences with tales of his rugged adventures on the exotic Alaska Peninsula. [16] After attending one of Hubbard's lectures, an admiring fan wrote:

I want to sincerely thank you for the most enjoyable entertainment of my life. I was on the edge of my seat during your whole wonderful talk. In my opinion you are the foremost speaker in the country today, and my enthusiasm knows no bounds regarding your performance." [17]

Apparently, the man was so inspired by Hubbard's Aniakchak adventures that he planned to move his family to Fairbanks. This was surely the type of inspired performance that Hubbard gave to NPS staffers on that November day.

Besides lectures, Hubbard wrote numerous books and articles, and made several films. His works collectively constructed an image of Aniakchak that offered a remote and dangerous geographical backdrop for thrills, risk, melodrama, camaraderie, and wonder, especially God's omnipotence in nature. [18] According to Price, Hubbard excelled at producing visual imagery, verbally in his books and lectures and artistically in his photos and films. [19]

|

| Father Hubbard says Mass at camp on the north shore of Surprise Lake. Steaming Half Cone and the 1931 cone behind Vulcan Dome are also visible, 1932. Bernard Hubbard, S.J., Alaskan Photograph Collection. Photograph courtesy of Santa Clara University Archives. ACK-32-276. |

The Glacier Priest modeled much of his rhetoric on the writings of Jack London, the most famous writer of the Far North, whose stories made the "killing cold" and encounters with wild animals synonymous with the Alaskan frontier. [20] Hubbard also followed news stories about the polar explorers, Lincoln Ellsworth, Roald Amundsen, Richard Byrd and Hubert Wilkins. He paid special attention to the symbiotic relationship between the media and those explorers. "From the very start," notes Price, "Hubbard understood the basic methods of creating, packaging, and flavoring news." Moreover, the Jesuit historic tradition of exploring unknown regions also shaped Hubbard's vision and was a practice with which he deeply identified. When first offered a membership into New York's famed Explorers' Club, Hubbard declined, replying that he was already a member of "a far older Explorers' Club, the Jesuit Order." [21] Whether Hubbard was driving a dog team across the Yukon or celebrating Mass deep inside the Aniakchak crater, he always underscored the "Hubbard Mystique" and ultimately his Moon Crater myth was the image of the Frontier. As Price notes, "Rugged and exotic sites were important backdrops while conquests, exploration, danger and difficulty provided the story." [22]

The fact that Hubbard chose Alaska to play out his frontier drama is hardly surprising. In 1895, when Hubbard was a young boy, he loved to explore the coastal mountains near Santa Cruz where his family maintained a ranch. Two years later, the American public began to notice Alaska when nuggets discovered on the Klondike River instigated a gold rush to the Far North. A young Bernard, filled with familiar images of the romantic California forty-niners, undoubtedly idealized the heroic gold prospectors and became suddenly aware of an Alaskan frontier. Later, while studying at Santa Clara College, Hubbard, like nearly every student of the Progressive era, was likely introduced to the teachings of historian Frederick Jackson Turner, who argued that the dramatic struggle with nature on the western frontier created a distinctive American character of individualism and self-reliance. Popular writers of the era quickly linked America's new golden territory to the conquest saga, and Alaska not only captured the attention of the young geology professor, but the Far North entered the national imagination as the final chapter in the story of the American West, the last frontier. [23]

From an early age Bernard Hubbard, a life-long Californian, viewed himself as a player in the national saga of the American frontier. "My childhood days in Santa Cruz were happy ones," wrote Hubbard in his memoir. "We even went to the country for a month's vacation each year. . .we went by stage coach, a cloud of dust along a one-rut dirt road. And what a wonderful adventure that ride was!" [24]

For Hubbard, as with Frederick Jackson Turner, the frontier saga was characterized by a struggle with a demanding, threatening, and frequently beautiful, but usually unknown natural foe. While studying theology in Innsbruck, Austria, Hubbard began to craft his frontier image in the mountainous landscape of the glacier-strewn Alps. As Hubbard tells the story, it was the Tyrolean villagers who gave him the nickname der Gletscherpfarrer—The Glacier Priest—for they noticed that the young theologian spent more time conquering glaciers than he did in Church. [25] After returning to the States, a friend at the United States Geological Survey (USGS) alerted Hubbard to a geological formation named Aniakchak, that agency surveyors had discovered in Alaska in 1922. By then, Hubbard, who was making a living speaking to large, mostly non-academic audiences, had learned to communicate the immediacy, awe, and thrill of conquering rugged, remote places. After hearing about this new natural wonder, Hubbard later wrote his religious superior that he was sure Aniakchak would be his "magnum opus and crowning effort." [26]

In his first book on Alaska, Mush, You Malamutes! Hubbard provided a first-hand account of his expedition into Aniakchak in his carefully named chapters "Flying the Moon Craters of Alaska" and "Aniakchak Explodes." In "Moon Craters" Hubbard, along with Harry Blunt, chief pilot of the Pacific International Airways, and Al Monson, his co-pilot, attempt to land an airplane in the crater just a few weeks after Aniakchak erupted on May 1, 1931. At first sight of Aniakchak, Hubbard described the crater as "the most terrible prelude of hell I could ever imagine." As Hubbard tells the story, when the craft was directly over the crater, the airplane's engine "refused to respond" and became caught in a down draft, with its nose pointed straight down. As the plane and its passengers were being sucked toward the erupting mass of hot gasses, "Blunt dove the plane straight down and with the speed of the dive righted the plane and roared away back into the Aniakchak Canyon through a huge rift in the volcano walls called The Gates." [27]

After his near-death experience, Hubbard wrote that he had escaped danger because prior to his departure from the Yukon River village of Holy Cross en route for Aniakchak, Hubbard had scribbled on a piece of paper the message, "Pray for the safety and success of our flight to the Moon Craters," and signed it "The Glacier Priest." Flinging the paper out the window of the airplane, Hubbard observed a young Yup'ik girl he knew as Verna pick it up. "When all is said and done," explained Hubbard, "I have my own idea of how we escaped danger on this occasion:"

Six weeks later when the exploration of Aniakchak was completed on foot I flew back to Holy Cross after one more ineffectual attempt to land inside the crater. Stealing alone into the quiet and peace of the beautiful Mission Chapel, after a few minutes spent in prayer of thanksgiving, I knelt a moment before the Blessed Virgin's altar. A bit of paper in the hand of the statue excited my curiosity. It looked familiar. I reached up and took it and tears came unbidden to my eyes as I read it. It was the note I had dropped from the plane that little Esquimo Verna, of Napararemiut, had found and with the faith that moves mountains, even erupting ones, had confided to the care of the Mother of God and Queen of Angels.

Little Verna may or may not have been Hubbard's guardian angel in the Moon Crater, but the story proved Hubbard's ability to expertly spin a good tale—a tale laced with danger, drama and divine intervention.

Still, the Moon Crater was more than just a backdrop for his rugged adventures. Hubbard probably truly believed that his guardian angel watched over him while he either trekked or flew into an active volcano. To Hubbard, places like Aniakchak may have been a source for riveting storytelling, but the crater was also a source of deep spirituality. From Hubbard's viewpoint, such a natural wonder was clear evidence of God's plan. On the summer evening that inspired the "Moon Craters" article, while the men of the expedition sank into slumber at their campsite, Hubbard, so excited by "the events of the afternoon and the promises of the morrow couldn't sleep and decided to see what the crater was doing in the starlight." [28] Within the Caldera walls stood Aniakchak's volcanic landforms and accretions washed in moonlight. "Looking up at the moon high in the silvered blue," recalled Hubbard, "I had one of those wondrous moments of translation that come sometimes to one in the wilderness." [29]

It may seem as though Hubbard's two visions of Aniakchak—a place to conquer and a place to worship—were contradictory. In fact, they reflect two competing views that merged and eventually formed the Alaskan frontier image. In that paradoxical synthesis, Alaska is both that place where rugged individualism triumphed over the harsh environment and is the epitome of nature undefiled. Hubbard's Moon Crater myth contained both viewpoints.

And, like the "sourdough" that fittingly took his place at the center of the Alaska saga, Hubbard took central stage in Aniakchak's Moon Crater myth. The melding of rugged individualism and incredible scenic beauty translated into a very powerful and comprehensive image of man and his relationship to the natural world. Indeed, it is this image that first caught the attention of the National Park Service.

Scholars who have written about the NPS, like Theodore Catton and Richard Sellars, agree that in the goal of preserving remnants of the wild landscapes of the frontier, the parks were from the beginning a part of the romantic western lore. From patrolling the remote backcountry to living in primitive, wood-heated log cabins, for many park rangers, working in the parks seemed a kind of lingering frontier experience. [30] As Catton points out, "Alaska's mythic identity as the nation's last frontier had an enormous bearing on the original conception of Alaska's first national park." [31] And without a doubt, it greatly shaped the making of Alaska's other national parks a half-century later.

While Hubbard neither discovered the crater nor was the first to describe it, it is his view of Aniakchak that promoted the region and put the remote volcano on the map. As National Park Service historian Frank Norris notes, "The [Aniakchak] eruption would doubtless have slipped into ignominy had it not been for the efforts of Father Bernard R. Hubbard." [32]

Thus, the message Hubbard relayed to Director Albright and his NPS staff was that Aniakchak was a land without equal. Exploring the Caldera was "not unlike invading the domains of Jupiter, Pluto and Neptune." [33] When the party stood at the edge of the crater, they saw "a land of lifeless, ashen desolation." [34] Aniakchak was a "moon crater" here on earth. Although Hubbard's saga included danger, difficult conditions in a remote landscape, and adventure in, what the Glacier Priest commonly referred to as, "the name of science," it contained little information as to what actually happened in the region. If Albright asked the Glacier Priest to shed light on Aniakchak's past, the so-called Alaska expert would have replied as he always did to that question, "No one knows, for history is silent on the subject." [35]

Perpetuating the Moon Crater Myth

A national park should represent a vignette of primitive America.... Yet if the goal cannot be fully achieved it can be approached. A reasonable illusion of primitive America could be recreated, using the utmost in skill, judgment and ecologic sensitivity. This in our opinion should be the objective of every national park and monument.

—A. Starker Leopold, et al.

"Wildlife Management in the National Parks"

It turned out the National Park Service failed to make Aniakchak a park unit in 1931. Inclusion into the park system would take another fifty years. With little investigation of the region's natural and cultural resources during the interim, Hubbard's interpretation of Aniakchak as an exotic, mysterious and uninhabited place consequently stuck. Initially, Albright had hoped to prepare a monument proclamation for President Herbert Hoover to sign. But after park plans were distributed throughout the Department of Interior earlier that year, the Aniakchak proposal first met resistance from the USGS, because of the area's potential for oil development. [36]

The most significant resistance to the Aniakchak proposal, however, came from inside NPS. Opposition came in the form of two competing monument proposals, both of which were designed to protect wildlife populations. On one side, the conservation community was lobbying for a national monument on Chichagof Island in order to protect its brown bear population. On the other side, Katmai National Monument was being considered for expansion. Then, sometime in early April 1931, NPS officials decided to expand Katmai National Monument. Officials reasoned that expanding Katmai gave the agency the opportunity to protect a well-known population of bears that had been increasingly threatened by trophy hunters and sport fishermen. In contrast, Aniakchak's resources—despite Father Hubbard's Washington lecture—were not particularly well known. Furthermore, NPS officials felt that because the site was so remote, the area's geological and biological resources were not in danger. [37]

|

| Father Hubbard talked about Aniakchak as being a violent moon crater, but also highlighted the crater's natural beauty as illustrated in this photograph that depicts Black Nose reflected in Surprise Lake, 1932. Bernard Hubbard, S.J., Alaskan Photograph Collection. Photograph courtesy of Santa Clara University Archives. ACK-00-198. |

Thus, on April 24, 1931, President Hoover signed a presidential proclamation expanding Katmai National Monument. By 1932, the agency had discarded both the Aniakchak and Chichagof proposals. The matter of an Aniakchak National Monument was dropped and the NPS did not consider it again until the 1960s. From Director Albright's point of view, Aniakchak was positioned about as far away from Washington D.C. as a place could be and still remain on the North American continent. The decision to manage one larger monument on the Alaska Peninsula rather than take on the logistical headache of managing two smaller monuments made sense. Without direct attention from federal researchers and administrators, information about Aniakchak floundered somewhere between fact and fiction. Thus, the alien Moon Crater of Earth remained on the fringe of America's national parks, literally on the frontier of the NPS system.

* * *

In the mid-1960s, when NPS officials returned their attention to Aniakchak, experts still knew virtually nothing about the central Alaska Peninsula. Some NPS staff may have been aware of the data Albright had collected relative to the 1931 proposal, but "beyond that," reasoned Norris in The Administrative History of Aniakchak, "information was probably limited to that written by Father Hubbard and by U.S. Geological Survey personnel." [38] So when political pressure brought about by the growing environmental movement forced a shift in the NPS management of natural resources, Hubbard's Moon Crater myth was adopted as the impetus for the new proposal. Accordingly, the NPS perpetuation of the Moon Crater myth reflected the broader revitalization of the agency's ecological purpose.

In the decades after the 1930s, National Park Service managers had focused their attention on recreational tourism rather than on a more scientific approach to preserving nature. Then, in 1963, just as Mission 66—the apex of a half-century of recreation tourism management—was approaching conclusion, experts from outside the agency published a landmark document called the Leopold Report, which stressed the preservation of ecological integrity in parks. [39] In the climate of activist environmentalism, outside groups with enormous political clout directly influenced a shift in the NPS management philosophy. The new philosophy, which was based upon the broad-ranging conclusions of the Leopold Report, emphasized policies that more closely resembled those fostered by wildlife biologists of the 1930s than any time in the years that followed.

|

| The violent moon crater comes alive. Hubbard and one of his companions investigate what is probably Slag Heap located in the 1931 tephra mantle, ca. 1931. Bernard Hubbard, S.J. Alaskan Photograph Collection. Photograph courtesy of Santa Clara University Archives. ACK-00-196. |

The Leopold Report stated that the purpose of NPS management should be to make each national park "represent a vignette of primitive America." [40] The goal, then, was to manage natural wonders like the Aniakchak Caldera in their natural state so that parks could "be maintained . . . as nearly as possible in the condition that prevailed when the area was first visited by the white men." [41] Although Congress passed the National Historic Preservation Act (NHPA) in 1966 and directed the National Park Service to manage and consider the impacts of actions on "historic properties," most NPS managers at the time believed this meant impacts on properties such as nationally and architecturally historic buildings, well-known archeological sites, and historic battlefields. There was no reason to think that such properties would be found in what was perceived as pristine wilderness. Far off places like Aniakchak were sought for inclusion into the park system for their impressive natural wonders.

In the 1960s, then, when landmark preservation legislation was implemented, it was the Leopold Report, not NHPA that influenced how individual personnel, from the superintendents down to the park rangers, perceived their role in managing park resources. In his book Preserving Nature in the National Parks, historian Richard Sellars notes that "the Leopold Report became a kind of call to arms for the Park Service . . . that the Service should preserve or create the mood of wild America." Although the Leopold Report reflected a relatively sophisticated understanding of ecosystems and the complex interrelatedness of nature, contemporary historians point out that the Leopold Report directed managers to maintain a landscape of a pioneer past, and consequently, reinforced rather than replaced the frontier myth as it related to national parks. As Sellar states, "this New World imagery suggested a kind of wilderness pastoral." [42] To preserve nature, the primary goal was to insulate delicate ecological relationships from human disturbances rather than to understand how humans fit into those relationships—that goal would come 30 years later. [43]

With political momentum initiated by the combined efforts of the 1964 Wilderness Act and the Leopold Report, George B. Hartzog, Jr., who became NPS director in January 1964, saw an opportunity to secure the protection of "surviving landmarks of our natural heritage." Hartzog recognized, however, that if any significant park system growth were to occur, that growth would have to be in Alaska. That November, the director appointed an Alaska Task Force to prepare an analysis of the "best remaining possibilities for the Service in Alaska." The report that emerged from that effort, called Operation Great Land, evaluated thirty-nine zones and sites across the state that contained recreational, natural, or historic value. One of those areas was the Aniakchak Crater Zone. [44] Meanwhile, in a similar report on Alaska lands, a U.S. Fish and Wildlife biologist, Roger Allin, recommended that NPS officials pay "early attention" to the Service's new National Natural Landmark (NNL) program. [45]

One year before the Leopold Report was published, the Secretary of the Interior created the National Natural Landmark program to identity and encourage the preservation of areas with unique and significant natural value. Researchers for the National Natural Landmark program determined that Aniakchak Crater was fully eligible as a national natural landmark. Consultants hired to assess the Caldera found that "from no viewpoint is Aniakchak unimpressive." [46] Federal status not only acknowledged the goals set forth for Aniakchak in 1931 but in the spirit (or perhaps even the pressure) of the Leopold Report, NPS adopted Hubbard's Moon Crater Myth: that Aniakchak is sublime, mysterious and void of people. For example, in the evaluation report for the National Natural Landmark, author Ellis Taylor described the crater in convincing Hubbard fashion:

Aniakchak, the real estate agent would say, has everything. Scientific importance, popular appeal, dramatic, heroic proportions, a mysterious past and an unpredictable, possibly spectacular geologic future, even hot and cold running water. [47]

Taylor not only advanced Hubbard's Moon Crater myth in the NNL report, but when describing Aniakchak's natural values, the researcher applied the principles of the Leopold Report perfectly: "To the visual features must be added the sense of violation..." wrote Taylor, "...as though one walked in a primeval Eden, where the animals were tame and unafraid, and where the silence, over the great barren ash plains, seemed weighty with meaning dimly understood." [48]

* * *

The crowning achievement in the growth of Park Service activities during the Leopold era came with the extensive planning for new parks in Alaska as mandated by the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act (ANCSA). On December 18, 1971, President Nixon signed ANCSA into law, which set into motion nine years of activity regarding the disposition of Alaska's federally managed lands. [49] According to ANCSA, any lands proposed for one of the four federal conservation systems—the Fish and Wildlife Service, the Bureau of Land Management, the U.S. Forest Service, and the National Park Service—had to be withdrawn within nine months and Interior Department officials recognized that a preliminary land withdrawal needed to be made within ninety days. "Based on those deadlines," observes Norris, "the NPS had no time to waste in beginning its planning effort." [50] Immediately, a thirty-five-member Alaska Task Force was created to compile available information about the proposed park units. Team 4, which was organized to produce reports for not only the Aniakchak proposal, but Katmai, and Lake Clark proposals, too, was faced with the dilemma of lack of time and data. NPS, therefore, paid little attention to Aniakchak. As late as 1971, Department of Interior personnel were still considering a "Proposed Aniakchak National Wildlife Refuge" that would be managed by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. [51] When the agency did finally begin to consider Aniakchak's inclusion into the park system, much of their information came from books authored by Father Hubbard. [52]

Tight congressional and departmental deadlines, along with intense surveillance from both environmental and private interests groups, added to the pressure and created a kind of chaotic atmosphere in federal circles during the early 1970s. ANCSA decreed that by December 18, 1973, the Secretary of the Interior had to issue a full legislative recommendation on which Alaska lands would be considered for the four conservation systems. Between March 1972 and June 1973, Alaska Task Force personnel were asked to supply sufficient resource information for a preliminary draft environmental statement and master plan.

Again, agency language and overall interpretation of the Caldera and surrounding landscape echoed Hubbard's moon crater myth. For example, agency researchers claimed that the "Aniakchak Caldera is a raw and rugged volcanic feature laying in a landscape that is, because of its remoteness, little affected by human occupancy." They also noted that "many visitors are impressed by the crater's sense of mystery and speak of their own insignificance when compared to this great volcanic feature." [53] M. Woodbridge Williams, chief photographer for the Alaska Task Force at the time, in articles for The Explorers Journal and National Parks and Conservation Magazine made no effort to harness his personal feeling towards the area; he referred to Aniakchak as a "kingdom of Genesis." [54] These phrases inspired an ethnocentric understanding of the area: that Aniakchak represented a primitive America and claimed an untouched, unknown—even Biblical—past.

Still, in spite of Hubbard's overly used rhetoric, the NPS did not remain stagnant when it came to research, for, during the decade, the agency did what it could to gather new information about the proposed unit. Most studies, however, emphasized natural rather than cultural resources. For example, in 1977, NPS deferred to the USGS to complete the first of several agency-sponsored geological studies of the Aniakchak Caldera. Other areas of research contained plant succession studies. Alaska Department of Fish and Game (ADF&G) sponsored a bear migration study that was conducted from 1970 through 1975. Except for Merry Tuten's study on local hunting patterns conducted between 1975 and 1977, which contained preliminary data for future subsistence and ethnographic studies, no surveys of the area's cultural resources were conducted in the post-ANCSA planning period.

In 1980, fifty years after Hubbard ascended Vent Mountain and predicted that Aniakchak Caldera "enclosed a potential national park," the federal government made the Glacier Priest's prediction a reality when Congress passed the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act (ANILCA), the legislative culmination of ANCSA. Two years before, in December 1978, President Jimmy Carter had made the Caldera the centerpiece of Aniakchak National Monument when he proclaimed the area a unit of the National Park Service system. Carter's action was sanctioned two years later, when Congress designated the Monument and Preserve by section 201(1) of ANILCA on December 2, 1980.

|

| Autographed photograph of Father Hubbard and his trusted dog, Katmai. Courtesy of Katherine Johnson Ringsmuth, Anchorage, AK. Published in Cradle of the Storms by the Dodd, Mead & Company, 1935. |

With the establishment of the Aniakchak National Monument and Preserve, Hubbard's moon crater myth continued to influence park researchers. As late as 1987, park historians still described the area within the historical context of Father Hubbard. [55] Aniakchak continued to be treated as a sublime backdrop to commemorate the Glacier Priest's historic "firsts." Like Hubbard, resource practitioners seemingly ignored all human activity that contradicted their concept of wilderness, unless, of course, that activity included a terrorizing flight into an erupting volcano.

The National Park Service contributed to this problematic interpretation by continuing to manage the Aniakchak unit as a frontier. According to park officials, "the purpose of Aniakchak National Monument and Aniakchak National Preserve is to protect and interpret for the benefit, inspiration, and education of present and future generation of the world's largest dry calderas, the Aniakchak River and the scenic, and scientific and biological values associated therewith." [56] In keeping with the Leopold philosophy, Aniakchak was to be managed for its natural wonders, not its cultural resources.

Although the operations plan was only meant to be temporary, the National Park Service decided to "manage Aniakchak as a unit of Katmai National Park, under the supervision of the Alaska area office." [57] In a decision that has lasted to this day, it was determined that Katmai National Park and Preserve's offices in King Salmon would directly manage the monument, making the residing superintendent the manager of both the Katmai and the Aniakchak NPS units. Despite plans the agency had laid out during the mid-1970s, managers made no attempt to establish a headquarters facility at Port Heiden. [58] Similarly, no trails, campgrounds, or ranger stations were constructed within Aniakchak boundaries. Because staff attention quickly turned to the far more popular Katmai unit, management objectives in Aniakchak fell to the wayside. No NPS personnel, in fact, visited Aniakchak for more than one and a half years after President Carter signed ANILCA into law. [59]

When Park Service staff in King Salmon did attempt to establish a presence in Aniakchak, it was inconsistent at best. In 1982 a seasonal ranger was hired to conduct patrols in Aniakchak, but according to the superintendent's annual report, "the logistics were terrible, weather worse, and it was all compounded by a complete lack of radio communication." [60] In the summers of 1983 and 1984, NPS did station two rangers at Aniakchak Bay in an old bunkhouse, built by commercial fish packers to house fish trap workers in the early decades of the twentieth century. Then, in 1986, NPS hired a resource management specialist to focus on Aniakchak issues. Working from the King Salmon administrative office, this was the only full-time staff person assigned to the Aniakchak unit. That year the general management plan, which called for two seasonal rangers to staff Aniakchak, was approved. Despite the mandate, rangers visited the unit only infrequently over the next two decades. Aniakchak lacked an NPS presence from 1985 through 1987 and only in 1988 and again in 1991 were rangers present for an entire season. [61]

Moreover, rangers, who were dropped off for the duration of the season, experienced a kind of frontier isolationism. Separated, rangers maintained very little contact and support from headquarters. Such isolation made it impossible to enforce illegal activities that took place inside the park unit. Although rangers established agency presence, recorded observations of the area's natural and cultural resources, and apprised park management about human use levels, except for brief visits, no NPS rangers have been stationed at Aniakchak since.

* * *

Even today, Hubbard's story and persona resonates with park management and visitors alike. With only 154 recreational visits made to the Aniakchak Caldera reported in all of 2003, it is easy to understand that visitors to the crater might feel as though they have entered a large and lonely universe. In an Anchorage Daily News article printed in 2005, the headlines declared: "Aniakchak: National Monument provides extreme solitude, adventure." [62] One rare hiker who was interviewed by a local newspaper described the area as "magical." Another noted, "Spectacular is the best word to explain much of the monument." Similar to sentiments made by Hubbard and his companions over seventy years ago, both visitors agreed: "In the week there [Aniakchak Caldera], it was remarkably quiet and isolated." [63]

Like the rangers who shared parallel experiences, this kind of frontier isolationism is heightened as the NPS continues to maintain a transient presence in the area. Not so unlike the New World must have seemed to the European explorers, Aniakchak remains one of the least visited and one of the most expensive spots on the North American continent to access. Still, as more people discover Aniakchak, little by little, Hubbard's Moon Crater myth is being dismantled. Some interviewed visitors advised, "The [Park Service] web site on Aniakchak makes it sound like you're going to the end of the earth." But as one of the adventure seekers was quick to point out, "For the people with the right skill, access to the monument is unbelievably easy and attractive." [64]

* * *

In many ways, it is easy to understand why Hubbard was so appealing. He was exactly the kind of companion you would want on a camping trip into the Aniakchak Crater, for he was passionate, optimistic and fun. "The fascinating thing about him," recalled Bill Regan about his friend years later, "was that he was just such a tough old mountain goat." [65] For his companions, as well as for those who read his works years later, Hubbard personified our need for wonder, our excitement for mysteries, and our desire for heroes. He brilliantly played upon our need to believe that blank spaces still existed on our blue and green spinning sphere. Perhaps he understood that sometimes fiction fills our societal needs as significantly as fact. There is no doubt that Aniakchak National Monument and Preserve is a wonder world. It is truly a national treasure. The National Park Service, in its attempt to include, preserve, and, ultimately, to protect Aniakchak in its natural state, was certainly doing its best to fulfill its mission to promote and regulate the use of the park so that Hubbard's geological wonder world would be left unimpaired for the enjoyment, education, and inspiration of future generations.

Still, Aniakchak was not terra incognita. Hubbard witnessed first-hand commercial trap fishing in Aniakchak Bay, he stayed in cabins built by families who trapped throughout Aniakchak, and even investigated several Native subterranean houses, clear evidence that Aniakchak was anything but a lifeless moon crater. Indeed, Aniakchak remains a place of wonder, inspiration, and yes, solitude. But, when our myths ignore the exploitation of the environment or the marginalization of people, then we cannot allow history to remain silent.

Father Bernard R. Hubbard never lived to see his beloved Geological Wonder World made into a national monument. He died at age 73 in Santa Clara on May 28, 1962, following complications arising from his fifth stroke. Recognizing Hubbard's passing, Newsweek wrote:

Died: The Rev. Bernard Rosencrantz Hubbard, 73, the Glacier Priest, a tireless Jesuit who led 32 expeditions to Alaska and once listed the requisites of an explorer as "a strong back, a strong stomach, a dumb head, and a guardian angel." [66]

Hubbard may have been strong, but he certainly was not dumb, and if he did have a guardian angel, then it flew with Hubbard into the prelude of hell. [67] Indeed, it is a story the Glacier Priest surely told at the Pearly Gates—where he undoubtedly packed them in up there, too.

NOTES

1Willoughby, "The Moon Craters of Alaska," 53.

2Price, Adventuring with the "Glacier Priest," iii.

5Beau Riffenburgh, The Myth of the Explorer (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1994), 12.

7Horace Albright, Memorandum for Mr. Crammerer, Mr. Demaray and Fr. Brooks, December 23, 1930 in "Aniakchak, Alaska" folder, in Box 658, File 0-35, Entry 7, RG 79, NARA DC.

8Norris, Isolated Paradise, 426.

9Richard West Sellars, Preserving Nature in the National Parks: A History (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1997), xii.

10Theodore Catton, Inhabited Wilderness: Indians, Eskimos and National Parks in Alaska (Albuquerque: University New Mexico, 1997), 68.

11A. Starker Leopold et al., "Wildlife Management in the National Parks," The Living Wilderness, Spring-Summer, 1963, 13. Although the so-called Leopold Report was published by the NPS in 1963, its idea was not new. According to Ted Catton, Dr. Joseph Grinnell had stated it in nearly so many words in 1916 and by a team of NPS biologists in 1931. Catton, 68.

12Willoughby, "Summer in the Moon Craters of Alaska," Alaskans All (1939), 43.

13Bernard Hubbard, S.J., "A World Inside a Mountain: Aniakchak, the New Volcanic Wonderland of the Alaska Peninsula, is Explored" National Geographic,September, (1931); Beverly Jones, Director, "Alaska's Silver Millions" (American Can Company, circa 1935).

14Dick Douglas, In the Land of the Thunder Mountains: Adventuring with Father Hubbard Among the Volcanoes of Alaska (New York: Brewer, Warren and Putnam, 1932), 4-5.

15Price, 42; In a memorandum to director Albright, Wallace R. Atwood, evaluates the pros and cons of making a "Crater National Monument in Alaska." Atwood cites Father Hubbard, which he calls an "enthusiastic scientist" as one of the individuals with whom he counseled while writing the report. The memorandum is dated January 21, 1931. In "Aniakchak, Alaska" folder in Box 658, File 0-35, Entry 7, RG 79, NARA, DC.

16"Hubbard, Bernard," Current Biography (1943), 320-323.

18Mush, You Malamutes! (New York: American Press, 1932); Cradle of the Storms (New York: Dodd, Mead & Co., 1935); "A World Inside a Mountain: Aniakchak, the New Volcanic Wonderland of the Alaska Peninsula, Is Explored," National Geographic (Sept, 1931): 319-345; "Aniakchak, the Moon Crater Explodes" Saturday Evening Post (Jan, 1932): 6-7; "Exploring the Alaskan 'Moon Craters'" New York Times Magazine, October 12, 1930, 8-10, 23; Beverly Jones, Director "Alaska's Silver Millions" (American Can Company, circa, 1935); Truman Talley, Producer, Aniakchak (Fox Films Corp, 1933).

20In the chapter titled, "New Preparations" Hubbard compares the dogs he brings to Alaska to those in Jack London's Call of the Wild. Hubbard, Cradle of the Storms, 80.

23Stephen Haycox, Frigid Embrace: Politics, Economics and Environment in Alaska (Corvallis: Oregon State University Press, 2002), 4-5.

24Bernard Hubbard, S.J., From Sea to the Mountains, autobiographical manuscript (Hubbard Collection, Michel Orradre Library, Santa Clara, University).

27Bernard Hubbard, S.J., Mush, You Malamutes! (New York: The American Press, 1932), 49-50.

28Willoughby, "Moon Craters," 49.

35Willoughby, Alaskan's All, 44.

39Sellars, 207, 214. Other historians who have challenged the notion of managing "wilderness" in national parks are William Cronon in "The Riddle of the Apostle Islands: How do you manage a wilderness full of human stories?" and Roderick Nash in "The American Invention of National Parks."

40A. Starker Leopold et al., "Wildlife Management in the National Parks," The Living Wilderness, Spring-Summer, 1963, 13.

Although the so-called Leopold Report was published by the NPS in 1963, its idea was not new. According to Ted Carton, Dr. Joseph Grinnell had stated it in nearly so many words in 1916 and by a team of NPS biologists in 1931. Catton, 68.

45Roger W. Allin, "Alaska Plan for Action, November 1966," in Roger Allin 1966 Report file, Box #6, Swem Collection, Department of Public Lands.

46Alaskasearch, Ltd., "National Natural Landmark Study, Report I," 28 July, 1967, at AHL and AKSO-RNR, Chief interagency Resource Division.

51Proposed Aniakchak National Wildlife Refuge, Alaska Area Office, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, December, 1971. HFE, Williss, Box B, in Aniakchak FWS 1971.

52Ibid., 442. See bibliography for the NNL report.

53NPS, Final Environmental Statement for the Proposed Aniakchak Caldera National Monument (Department of Interior, 1974), 27, 31.

54M. Woodbridge Williams, "Aniakchak: Kingdom of Genesis" National Parks & Conservation Magazine (Vol. 49, No 6, June 1975), 9; a reprint of the article appears in The Explorers Journal (vol. 65, No 1, March 1897), 2-7.

55Norris, 479; Sandra M. Faulkner, "Father Hubbard, the Glacier Priest" paper delivered at an Alaska Historical Society symposium, held in Fairbanks in October, 1987.

56NPS, "Draft Statement for Management, Aniakchak National Monument and Preserve," May 1983.

60"Superintendent's Annual Report," KATM/ANIA, 1982, 6.

61George Stroud and Lynn Fuller stayed in the CRPA Bunkhouse summer of 1983 and 1984. In 1988 Frank and Penny Starr spent the summer in the cabin. John Eppling and his wife Shakti, who served as a volunteer, stayed in the cabin in 1991.

62Craig Medford, "A New Adventure: Aniakchak National Monument's Overlooked Pack-and-Float Option Beckons" Anchorage Daily News, January 30, 2005, F-1 and F-2.

65Bill Regan, interview with Julie O'Keefe, 10.

67Bernard Hubbard, S.J., Mush, You Malamutes!, 49.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

hrs/chap1.htm

Last Updated: 03-Aug-2009