|

Geological Survey Professional Paper 329

Reconnaissance of the Geomorphology and Glacial Geology of the San Joaquin Basin, Sierra Nevada California |

INTRODUCTION

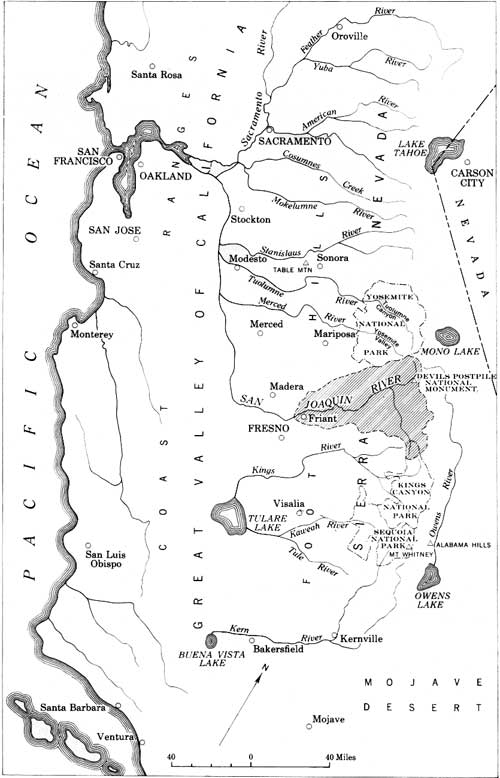

This report is based upon a reconnaissance of the upper basin of the San Joaquin River conducted in 1921, 1923, and 1927. By the upper basin (or what will hereafter, for convenience, be termed the San Joaquin Basin) is meant the mountain course of the San Joaquin River, situated in the central part of the west slope of the Sierra Nevada (fig. 1.) The San Joaquin Basin lies between the drainage basins of the Merced and the Fresno Rivers, on the northwest, and the drainage basin of the Kings River on the south. This report does not include the level plain at the west foot of the range which is traversed by the lower or valley course of the San Joaquin River—the San Joaquin Valley, as it is generally called, or the southern part of the Great Valley of California; neither does it include the drainage basins within the Sierra Nevada of the other rivers which join the San Joaquin River on the plain.

Like each of the adjoining basins and those of the other master streams of the west slope of the Sierra Nevada, the San Joaquin Basin is a natural geomorphologic unit that can advantageously be treated by itself.

The reconnaissance with which this report deals was undertaken for a 2-fold purpose: first, to extend geomorphologic and glacial studies made in previous years in the Yosemite region southeastward, as a first step toward connecting that region with the as yet isolated area, 100 miles distant, in the basins of the Kern, Kaweah, and Kings Rivers, which had been investigated some years before by Lawson (1904, 1906) and Knopf (1918); and second, to test the soundness of conclusions which the author had previously reached in the Yosemite region regarding the geomorphologic development and the glaciation of that region, and to determine their bearing on the history of the Sierra Nevada in general.

From preliminary map studies, it was expected that the San Joaquin Basin would prove to be a key area for the interpretation of the central and southern parts of the west slope of the Sierra Nevada, and this inference was fully confirmed.

The San Joaquin Basin, up to the the when these investigations were undertaken, had not been previously studied systematically. Very little was known of the geology of the area beyond the fact that its rocks are mostly granitic, except near the crestline of the range where metamorphic rocks prevail. Only one hasty reconnaissance had been made through it, namely, by Brewer's party of the California Geological Survey in 1864; but that initial exploration, as is evident from Whitney's report (Whitney, 1865) as well as from Brewer's original journal (Brewer, 1930) had yielded, besides a sketch map by Hoffman, only a few scanty geologic notes. To one who reads between the lines, it is plain that the party suffered many hardships not mentioned in its report, and that the overcoming of physical obstacles, and the ultimate safety of its members became problems of paramount importance to which scientific studies had to be largely sacrificed. Their reconnaissance is to be regarded primarily as of historic interest.

In the reconnaissance of 1921 the writer, therefore, found himself essentially in a virgin field. However, some conception of the outstanding landmarks of the basin had been gained previously from graphic articles published in the Sierra Club Bulletin and illustrated by excellent photographs; and by far the most valuable advance information about the region was obtained from the topographic maps that had been published about a decade previously by the U. S. Geological Survey.

Those parts of the San Joaquin Basin shown on the Mount Lyell, Mount Morrison, Kaiser, and Mount Goddard quadrangles were largely covered by the reconnaissance surveys. In addition, the foothill country shown on the Friant, Academy, and Dinuba quadrangles was given a cursory examination. Thus the San Joaquin River and its tributaries were traced from the peaks on the crest of the Sierra Nevada down to the mouth of the rock-cut canyon where the river begins its alluvial course over the sediments of the Great Valley of California.

The fieldwork consisted partly in analyzing the features of the landscape into elements belonging to successive surfaces of erosion, and partly in the systematic tracing and mapping of the moraines that mark the farthest extensions of the Pleistocene ice in each of the two well-defined and clearly distinct glacial stages. No means were found within the compass of the San Joaquin Basin for determining the age of any of the surfaces of erosion, owing to the absence of fossiliferous deposits. Nevertheless, the ages are not wholly indeterminate, for it was possible to correlate the erosion surfaces of this area with those previously recognized in the Table Mountain region of the Stanislaus basin (fig. 1), where fossils are present in the Tertiary stream deposits, and where the age of at least one erosion surface has been tentatively determined. No attempt was made to identify and map the different types of igneous rocks that constitute the great batholith of the Sierra Nevada and which form the prevailing country rock of the area, and no petrographic studies were undertaken in connection with the reconnaissance. Some attention was given, however, to the more important bodies of metamorphic rock, which are scattered here and there, and to the volcanic rocks, which consist of many small local flows of Tertiary and Quaternary age.

|

| FIGURE 1.—Index map showing location of the San Joaquin Basin. (click on image for a PDF version) |

The author's investigations did not cover the San Joaquin Basin completely, and consisted mainly of a reconnaissance of its geomorphologic and glacial features. The foothill belt; in particular, received only minor attention, but as it was not practicable in the the available to cover all parts of the basin with equal thoroughness, and as the foothill belt presents a set of geomorphologic problems of its own, deserving special investigations, it seemed best to present the studies made in their present incomplete form.

ITINERARY OF EXPEDITIONS

In the summer of 1921 (July 8—October 1), the author, with a small party, made a preliminary reconnaissance across the entire breadth of the rugged San Joaquin Basin and back, traveling on horseback and equipped with a pack train. Starting from Yosemite Valley, he entered the San Joaquin Basin by the little-frequented Fernandez Pass and thence descended into the valley of Granite Creek (pl. 1). Using Clover Meadow as a headquarters, the entire basin of Granite Creek and the so-called Jackass district to the south were explored. Crossing the North Fork of the San Joaquin River, the party then traveled successively to "77" Corral, to Reds Meadow and the Devils Postpile, and to Mammoth Pass; and finally up the Middle Fork of the San Joaquin River to its headwaters at Agnew Pass and Thousand Island Lake.

The party, doubling back, followed the Middle Fork southward to Fish Valley, ascended the upland toward Pincushion Peak, and cursorily examined the basin of Silver Creek. Then it descended into the valley of the South Fork of the San Joaquin River and followed it up to the Lower Hot Springs, where a side trip was made into Vermilion Valley2 and up the canyon of Mono Creek. Resuming its journey up the South Fork, the party traveled to Blaney Meadows and examined the area around Selden Pass, then continued up Evolution Valley, and using this as a base, explored Evolution Basin as far as the Muir Pass, as well as the rugged country around Mount Darwin, the Glacier Divide, and Mount McGee. The return was made down the South Fork to Blaney Meadows, over the Hot Springs Pass to Long Meadow, where the country at the head of Big Creek was covered; then on to Huntington Lake, northward over Kaiser Ridge, and down Kaiser Creek to Daulton Ranger Station. Scarcity of grass due to prolonged drought made it impracticable to keep the pack train in this area and compelled the party to hasten across the San Joaquin River to Placer Ranger Station. After a brief halt there, to examine the more accessible parts of the Chiquito Creek basin, the march continued in a northwesterly direction by Beasore and Mugler Meadows to the Chiquito Pass, where the Merced Basin and the Yosemite National Park were reentered on October 1.

2This valley is now occupied by Lake Thomas A. Edison.

In the spring, and early summer (July 3-30) of 1923, the lower part of the San Joaquin Basin, which is traversed by several roads, was visited by automobile. From Fresno, a reconnaissance was made through the foothills and up the grade from Tollhouse to Shaver Lake, Big Creek, and Huntington Lake. The return trip was made through the lower San Joaquin Canyon, which that year for the first the had been made accessible by the opening of automobile roads built by the Southern California Edison Company to connect its chain of power stations. During the remainder of the field season a second pack train expedition was made from the Yosemite Valley through the roadless western and central parts of the San Joaquin Basin, examination of which had to be abandoned in 1921 owing to lack of pasturage for the pack train. On this second trip, conditions were more favorable, and the was spent in the large tract stretching from Kaiser Ridge northward to the junction of the South Fork and Middle Fork of the San Joaquin River.

In 1927 (June 27—September 18) opportunity was had for a supplementary and somewhat more detailed examination of a limited area immediately surrounding Huntington Lake and extending southward to the valley of Dinkey Creek. This additional work seemed particularly desirable in view of the great hydroelectric developments centering about Huntington Lake, and the rapid transformation of the surrounding region into one of the major summer tourist centers of the Sierra Nevada. (See later paragraph on "Economic and Social Use." page 12.)

INVESTIGATIONS SUBSEQUENT TO FIELDWORK

Since this reconnaissance, a number of noteworthy studies have contributed to the geologic knowledge of the central and south-central parts of the Sierra Nevada. Those of special significance to this report may be briefly mentioned. Hans Cloos and Ernst Cloos (Ernst Cloos, 1933) have applied their technique of structure analysis to various parts of the Sierra batholith. Mayo (1930, 1934, 1935, 1937, and 1941; Locke, Billingsley, and Mayo, 1940) has extended these studies throughout the central and southern Sierra Nevada, including the San Joaquin Basin, by his regional investigations of the structures of the intrusive rocks and their relations to the metamorphic rocks. Erwin (1934, 1937) has made an intensive study of the metamorphic rocks and associated mineral deposits in the region at the head of the Middle Fork of the San Joaquin River. Blackwelder (1932) has studied the evidences of successive glaciations on the eastern flank of the Sierra Nevada. Macdonald (1941) has investigated the metamorphic and igneous rocks in the foothills belt of the western Sierra Nevada between the Kings and the San Joaquin Rivers. Webb (1946) has presented new evidence for the events in the evolution of the Middle Kern Basin, and has revised some of Lawson's earlier interpretations. The author (Matthes, 1930a, 1933a, 1933b, 1937, 1950b) has followed up geomorphologic studies in the Yosemite, Tuolumne, and San Joaquin Basins by related investigations in the basins of the west-slope rivers in the southern part of the Sierra Nevada, and by more intensive investigations at selected points along the eastern flank of the range, from the vicinity of Mono Lake southward to the Alabama Hills (fig. 1). As this report is being completed, Birman (1954) has published, in abstract, the results of a recent, detailed study of the glacial record along the South Fork of the San Joaquin River and its tributary, Mono Creek.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

During the summer of 1921, the writer was ably assisted in the field by Mr. Francis Cameron. The writer also wishes to acknowledge his indebtedness to officials of the Southern California Edison Company and the Forest Service of the U.S. Department of Agriculture for their courtesies in connection with this reconnaissance. Certain data in this report have been taken, with the permission of the Vanguard Press, from the chapter entitled "A Geologist's View" which the writer contributed to "The Sierra Nevada: the Range of Light" (Matthes, 1947). Data have also been taken, with the permission of the University of California Press, from the writer's volume, "The Incomparable Valley: A Geologic Interpretation of the Yosemite" (Matthes, 1950b). Grateful acknowledgment is made to Mr. Charles S. Denny, whose painstaking and critical review of the manuscript led to many constructive suggestions which were adopted.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

pp/329/intro.htm

Last Updated: 27-Jul-2009