|

Geological Survey 18th Annual Report (Part II)

Glaciers of Mount Rainier Rocks of Mount Rainier |

NARRATIVE.

(continued)

THE MOUNTAIN'S SUMMIT.

In the truncated summit of Mount Rainier there are three craters. The largest one, partially filled by the building of the two others, is the oldest, and has suffered so greatly from subsequent volcanic explosions and erosion that no more than its general outline can be traced. Peak Success and Liberty Cap are prominent points on the rim of what remains of this huge crater. Its diameter, as nearly as can be judged, is about 2-1/2 miles. Within the great crater, in the formation of which the mountain was truncated and, as previously stated, lost fully 2,000 feet of its summit, there are two much smaller and much more recent craters. The larger of these, the one in which we took refuge, is about 300 yards in diameter, and the second, which is an incomplete circle, its rim having been broken by the formation of its more recent companion, is perhaps 200 yards across. The rim of each now partially snow-filled bowl is well defined, and rises steeply from within to a sharp crest. The character of the inner slopes shows that much rocky material has been detached and has fallen into the cavities from which it was ejected. The rock in the crater walls is in fragments and masses, some of them well rounded and probably of the nature of volcanic bombs. In each of the smaller craters there are numerous steam jets. These show that the rock below is still hot, and that water percolating downward is changed to steam. These steam jets evidently indicate the presence of residual heat and not an actual connection with a volcanic center deep below the surface. All the evidence available tends to show that Rainier is an extinct volcano. It belongs, however, to the explosive type of volcanoes, of which Vesuvius is the best-known example, and there is no assurance that its energies may not be reawakened.

THE DESCENT.

In descending we chose the south side of the mountain, knowing from the reports of many excursionists who had ascended the peak from that direction that a practicable route could probably be found. Threading our way between numerous crevasses we soon came in sight of a bold, outstanding rock mass, which we judged to be Gibraltar, and succeeded in reaching it with but little difficulty. On gaining the junction of the rock with the snow fields rising above it, we found evidences of a trail, which was soon lost, however, and only served to show that our general course was the right one. A deep, narrow space between the border of Nisqually Glacier and the precipitous side of Gibraltar, from which the snow and ice had been melted by the heat reflected from the cliffs on our left, led us down to a shelf on the lower side of the promontory, which proved a safe and easy way to the crest of a rocky rib on the mountain side which extended far down toward the dark forests in view below.

Gibraltar is a portion of the cone of Rainier built before the explosion which truncated the mountain. It is an outstanding and very prominent rock mass, as may be seen in Pls. LXXIV and LXXVII, left in bold relief by the ice excavation which has carved deep valleys on each side. The rock divides the descending névé in the same manner as does The Wedge, and causes a part of the snow drainage to flow to the Cowlitz and the other part to be tributary to the Nisqually Glacier. The rocks forming Gibraltar consist largely of fragments ejected from the crater above, but present a rude stratification due to the presence of lava flows. When seen from the side and at a convenient distance, it is evident that the planes of bedding, if continued upward at the same angle, would reach above the present summit of the mountain. Gibraltar, like The Wedge and several other secondary peaks on the sides of Mount Rainier, are, as previously explained, the sharp, upward-pointing angles of large V-shaped masses of the original volcanic cone, left in bold relief by the excavation of deep valleys radiating from the central peak. On the backs, so to speak, of these great V-shaped portions of the mountain which now seem to rest against the central dome, secondary glaciers, or interglaciers as they may be termed, have excavated valleys and amphitheaters. In the V-shaped mass of which Gibraltar is the apex, a broad amphitheater-like depression has been cut out, leaving a bold cliff above it. The excavation of the amphitheater did not progress far enough up the mountain to cut away the apex of the V-shaped mass, but left it with a precipice on its lower side. This remnant is Gibraltar. An attempt will be made later to describe more fully the process of glacial erosion of a conical mountain, and to show that the secondary topographic features of Mount Rainier are not with out system, as they appear at first view, but really result from a process which may be said to have a definite end in view.

|

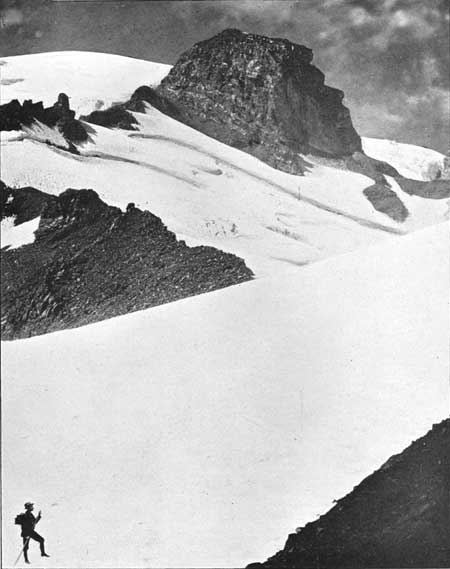

| Pl. LXIX. NÉVÉ ON THE EAST SIDE OF MOUNT RAINIER. |

Below Gibraltar the descent was easy. Our life line was no longer needed. Tramping in single file over the hard surfaces of the snow field, remnants of the previous winter's snow, we made rapid progress, and about noon gained the scattered groves of spruce trees which form such an attractive feature of Paradise Park.

Fortunately, we found Prof. E. S. Ingraham, of Seattle, and a party of friends, including several ladies, encamped in Paradise Park, and the hospitality of the camp was extended to us. During the afternoon we basked in the warm sunshine, and in the evening gathered about a roaring campfire and enjoyed the society of our companions, who were enthusiastic in their praise of the wonderful scenes about their camp.

PARADISE PARK.

The southern side of Mount Rainier is much less precipitous than its northern face, and the open park-like region near timber line is broader, more diversified, and much more easy of access. The general elevation of the park is between 5,000 and 7,000 feet, and it is several thousand acres in extent. Its boundaries are indefinite. It merges into the heavily forested region to the south, and in to more alpine regions on the side toward the mountain, which towers above it on the north. To the east it is bordered by Cowlitz Glacier, and on the west by Nisqually Glacier. Each of these fine ice rivers descends far below timber line. The small interglacier, known as the Paradise Glacier, may be considered as lying within the limits of the park.

Paradise Park presents many and varied charms. It is a somewhat rugged land, with a deep picturesque valley winding through it. The trees grow in isolated groves. Each bunch of dark-green firs and balsams is a cluster of gracefully tapering spires. The undulating meadows between the shady groves are brilliant in summer with a veritable carpet of gorgeous blossoms. In contrast to the exquisite charms of the groves and flower-decked rolling meadows are desolate ice fields and rugged glaciers which vary, through many tints and shades, from silvery whiteness to intense blue. Added to these minor charms, and towering far above them, is the massive summit of Rainier. At times the sublime mountain appears steel-blue in the unclouded sky, or rosy with the afterglow at sunset, or all aflame with the glories of the new-born day. Clouds gather about the lofty summit and transform it into a storm king. Avalanches rushing down its side awaken the echoes in the neighboring forest. The appearance of the mountain is never the same on different days; indeed, it changes its mood and exerts a varying influence on the beholder from hour to hour.

Something of the magnificence of Mount Rainier as seen by visitors to Paradise Park is revealed in the accompanying photograph (Pl. LXXI, here reproduced through the kindness of Mr. E. Curtis, of Seattle. The view was taken near sunset when the chill of evening was just beginning to dissipate the vapors that enshrouded the summit of the great peak.

While the central attraction to the lover of mountain scenery in Paradise Park is the vast snow-covered dome of Mount Rainier, there are other mountains in view that merit attention. To the east rises the serrate and rugged Tattoosh range, shown on Pl. LXXII, which is remarkable for the boldness with which its bordering slopes rise from the forested region about it and the angularity of its many serrate summits. This range has never been explored except by miners and hunters, who have made no record of their discoveries. It is virgin ground to the geologist and geographer. Distant views suggest that the Tattoosh Mountains have been sculptured from a plateau, probably an upraised peneplain in which there existed a great mass of igneous rock surrounded by less resistant Tertiary sediments. The softer rocks have been removed, leaving the harder and more resistant ones in bold relief to become sculptured by rain and frost into a multitude of angular peaks. This attractive, and as yet unstudied, group of peaks is in plain view from Paradise Park, and may be easily reached from them by a single day's tramp. Many other delightful excursions are open to one who pitches his tent in the alpine meadows on the south side of Mount Rainier.

TO LITTLE TAHOMA.

Bidding our friends in Paradise Park good-by, we resumed our journey early on the morning of July 26. Ascending toward Gibraltar until an elevation of about 10,000 feet was reached, we turned eastward for the purpose of traversing the eastern slope of the mountain and regaining our camp at Winthrop Glacier. After crossing the upper portion of Paradise Glacier, we traversed broad and but little broken snow fields to the brink of the valley down which Cowlitz Glacier flows. Beyond Cowlitz Glacier, at about the same level that we had reached, we could see the bold, cathedral-like crags of Little Tahoma, the upward-pointing angle of a secondary mountain mass which divides Cowlitz and Emmons glaciers. Not wishing to descend into the deep valley before us and climb out again on the farther side, we chose to cross the névé fields to our left and endeavor to pass over a rugged and much broken region where the main current of Cowlitz Glacier descends a rocky slope about a thousand feet high. In following the route chosen we became involved in a succession of crevasses and ice precipices, which caused much delay. Slowly working our way upward, we reached the base of the highest ice wall, but a vertical cliff of ice about 50 feet high barred all further progress in that direction. Reluctantly we turned back and, losing all the advantage we had gained by three or four hours of excessively hard climbing, went down the central portion of the Cowlitz Glacier until we reached the level of the highest grove of trees on its left bank, and crossing to the land chose a delightful and well-sheltered spot beneath low pine trees at which to rest for the night.

Our camp was perhaps half a mile below where the ice stream flowing southward from Little Tahoma, and named Ingraham Glacier on the map forming Pl. LXVI, joins the main Cowlitz Glacier. Our bivouac was in a delightful locality, and would have furnished a pleasant camping place if we had been provided with the necessary blankets and rations with which to make life comfortable. As it was, we had to sleep on the moss without covering, our feet to a blazing fire. For food each man had one hard-tack and a cup of tea, without sugar or milk, for each meal. Near at hand was a cascade of clear water, furnished by the melting snow fields on the back of the spur of which Little Tahoma is the culminating summit. A larger cascade a mile below tumbled over the rugged cliffs and awakened the echoes on the precipices across the glacier. The music of the falling waters filled the intervals of our broken sleep. The full moon shed a soft light over the white glacier and rugged rocks, and added a charm to a wild scene that under more comfortable conditions would have been considered one of the most fascinating we met during our excursion.

All of the Cowlitz Glacier in view was heavily snow-covered, and broken in a systematic manner by marginal crevasses which left the shore at angles of about 45° and trended upstream. The appearance of this glacier at a later stage in the melting of its covering of snow is shown on Pl. LXXVI. The glacier is deeply sunk in a well-defined valley, and is, perhaps, the most characteristic example of a glacier of the alpine type to be found on the slopes of Mount Rainier.

Rising with the sun and partaking of our allotted single hard-tack and a cup of tea, we climbed the rugged cliff at the base of which we had passed the night, taking a route explored the previous afternoon by Smith and Ainsworth, and gained the summit of the cliff overlooking Ingraham Glacier.

A deep descent of 500 feet over ledges of crumbling lava brought us to the hard ice below. An hour's tramp up the glacier and along the base of magnificent cliffs of volcanic agglomerate and lava in rude, irregular layers brought us to the sharp angle of rock at the base of Little Tahoma, against which the névé snows from the central dome divide. The descending snow meets the wedge of rock and is parted by it as the current is divided by the prow of a ship at anchor. The ice and snow, much shattered and standing in pinnacles, rises a hundred feet more against the obstruction in its downward course. The cliffs are or being cut away by the strong ice current, and rise above it in vertical precipices that culminate in sharp spires a thousand feet above the glacier. This proved a splendid locality for studying the manner in which the névé divides on reaching the medial portion of the main mountain side, and for seeing the modifications in the topography due to the erosion of glaciers flowing from the central dome.

To the north of Little Tahoma and flowing eastward is Emmons Glacier, the largest ice stream of Mount Rainier. This glacier is greatly broken, especially in its upper course, and has a peculiar feature not seen in connection with any other glacier. In its central portion there are two nearly parallel ridges of rock, which begin far up toward the summit of the main dome and descend for a mile or more below the level of the prow-like point of Little Tahoma. These parallel ridges appear from a distance to be medial moraines, and in part this is their true character. All along the dark belts in the center of the glacier, however, there are narrow and angular crests of rock in place, which project above the surface of the snow and ice. These crests of rock cause great crevasses to form in the ice flowing on either side of them and between them. For this reason Emmons Glacier is more difficult to cross than any other met with during our reconnaissance. The origin of the parallel rocky crests, the nature of which is shown to some extent on Pl. LXXIII, and their place in the topographic development of the mountain was not fully made out.

ACROSS EMMONS GLACIER.

The névé of Emmons Glacier abreast of the prow of Little Tahoma was so greatly shattered that, looking down on it from the cliffs against which the névé divides, no practicable way for crossing could be chosen. Going down onto the glacier and following its side under the shadow of Little Tahoma for about a mile, we found the slope more gentle, with fewer crevasses, and then turned our faces toward The Wedge, where we had left our blankets four days previously. A way across the glacier was finally discovered, however, by patiently making trial after trial and going about the ends of the widest breaks. Many narrow crevasses were jumped, others were crossed by frail snow bridges. By persistent effort we at length gained the narrow crest of rock in the center of the glacier, and although our goal was in plain view, many difficulties had still to be overcome before we reached our former camping ground.

|

| Pl. LXX. GIBRALTAR, A REMNANT OF THE CONE OF MOUNT RAINIER. |

A hasty lunch and a cup of coffee renewed our strength. Taking our blankets on our backs once more, we started on the homeward tramp down the Winthrop Glacier. The footprints made five days previously were clearly visible at first, but each impression stood in high relief, owing to the more rapid melting of the uncompacted snow about it. The descent was easy and rapid. By 5 in the afternoon we again joined the members of our party who had remained in the timber line camp on the west border of Winthrop Glacier.

THE RETURN.

Our plan was to carry our reconnaissance about the west slope of Mount Rainier, so as to gain at least a general idea of all of the glaciers flowing from the mountain, and of other features in the geography and geology of the region, but learning that the forest along the trail leading to Carbonado was on fire, a change became necessary.

Returning to our former camp on the west side of Carbon Glacier, plans were quickly made for dividing the party. Willis, with the camp hands, returned to the lower extremity of Carbon Glacier and thence to Carbonado, while Smith and myself, taking a small supply of rations, but without tents or blankets, turned our faces westward and visited Willis Glacier, Eagle Cliff, Crater Lake, and thence by way of the Spray Park trail and the main Willis trail also reached Carbonado.

Our reconnaissance extended from July 15 to 31, inclusive. Our route may be traced on the accompanying sketch map, Pl. LXVI, on which the glaciers and main topographic features of the mountain are indicated. The glaciers on the southwest side of the mountain between Willis and Nisqually glaciers were not visited, but some of their principal features were seen from distant points of observation.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

rpt/18-2/sec1-5b.htm

Last Updated: 28-Mar-2006