|

California Division of Mines

Speial Report 53 Igneous and Metamorphic Rocks of Parts of Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks, California |

MESOZOIC PLUTONIC ROCKS

(continued)

The Plutons

In the following discussion each pluton will be described separately with emphasis on features that distinguish the unit in the field. With regard to the 13 named plutons, it must be considered that this reflects an attempt by the writer to delineate all units not positively correlative. In some instances, units that may be correlative (e.g., Lodgepole and Pear Lake masses, Clover Creek and Giant Forest masses) are shown as separate units in the belief that only with the mapping of a larger area can a positive correlation be established or disproved.

|

| PHOTO 3. Well-developed foliation formed of drawn-out inclusions in the Giant Forest pluton near Bacon Meadow. |

|

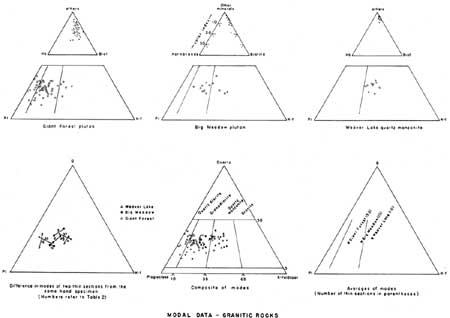

| FIGURE 3. Modal Data - Granitic Rocks. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

Aplite and pegmatite dikes are present in all of the plutons, but are not common. The aplite is a light-gray to white, fine-grained rock, with a sugary texture, consisting of quartz, potash feldspar, and sodic plagioclase, with local traces of biotite and hornblende. Pegmatite is much less common, but it is well distributed, and occurs as dikes, cores of aplite dikes, rims on aplite dikes, and bulbous knobs on aplite dikes, listed in the order of decreasing abundance. The pegmatite consists mostly of potash feldspar, quartz, and albite, and commonly shows graphic texture. Biotite and muscovite are less common, and pink garnet, epidote, and black tourmaline (schorlite) are only locally abundant. Tourmaline is particularly abundant northwest of the Ash Mountain Park Headquarters where it is invariably surrounded by or intergrown with quartz in vermicular and graphic patches. The encroachment of these tourmaline-quartz. masses into feldspar-quartz intergrowths indicates tourmaline replacement of feldspar.

|

| PHOTO 4. A dike of rock similar to the Giant Forest pluton cutting hornfels and schist west of Little Baldy. Darkening near the contact results from a concentration of hornblende that has formed by reconstitution of schist. |

Elk Creek Gabbro. Four small masses of gabbro totaling about a square mile in area, crop out along and near Elk Creek, an intermittent stream northwest of the Ash Mountain Park Headquarters. The gabbro is easily distinguished by extreme dark color, prominent hornblende, marked variation in grain size, and a dull gray to red dish-brown soil locally developed in areas of scattered outcrop.

Most specimens are about half calcic plagioclase and half dark minerals, with hornblende predominant. Augite, hypersthene, and red-brown biotite unlike that of the other granitic rocks are present in lesser abundance; olivine is rare. The most striking feature of the gabbro is the local development of poikilitic, brown hornblende crystals as large as 6 inches across (photo 20). Both the pyroxene and brown hornblende commonly are rimmed by pale green hornblende.

Potwisha Quartz Diorite. The Potwisha quartz diorite underlies about a square mile in the vicinity of Potwisha Camp. It has a distinctive dark-gray color, an abundance of dark inclusions and schlieren, and is readily distinguishable from the other units in the plutonic suite.

The quartz diorite is in gradational contact with the Giant Forest pluton, but is mapped separately because it has a distinctive color and mineral content. The abundance of dark inclusions and schlieren, and the nearness of gabbro and metamorphic rocks suggest the Potwisha quartz diorite is a contaminated facies of the Giant Forest pluton.

Cow Creek Granodiorite. The Cow Creek granodiorite is named from exposures along Cow Creek along the west side of the area. The granodiorite is light gray, and finer grained than the rocks of the Giant Forest pluton. Little is known about this unit as it was studied only briefly along Cow Creek and Yucca Creek, owing to the dense brush in this part of the area.

The specimens from Cow Creek are leucocratic granodiorite with predominant sodic andesine and only 5 percent biotite. The specimens from Yucca Creek have a similar mineral content, but a more granulose texture. Hybridization from the adjacent schist, which has a pronounced embayment along Yucca Creek, is a possible cause for this atypical granitic texture.

Clover Creek Granodiorite. Three small masses chiefly granodiorite, totaling about a square mile in areal extent, crop out near the West Fork of Clover Creek and south of Colony Meadow. These rocks are distinguished chiefly by a salt and pepper speckled appearance, resulting from imperfectly formed hornblende and sphene crystals sprinkled through the rock. The finer fabric of the Clover Creek rocks was used as the most significant factor in separating these rocks from the mineralogically similar Giant Forest rocks. Possibly the Clover Creek granodiorite masses are small stocks of the Giant Forest pluton, and consequently finer grained.

Tokopah Porphyritic Granodiorite. The Tokopah porphyritic granodiorite is named from exposures in upper Tokopah Valley in the eastern part of the area. The Tokopah pluton is probably the most distinctive rock in the area. It is notably porphyritic with stubby to equant, subhedral to euhedral, pink to gray microcline phenocrysts as large as 25 mm across, set in a medium-grained groundmass averaging 3 to 5 mm. Some of the plagioclase also is present as phenocrysts as large as 15 mm in length.

The microcline phenocrysts are probably late replacement crystals, despite the fact that the euhedral appearance suggests early formed crystals. The phenocrysts are commonly poikilitic, and include biotite and hornblende near the margin of the crystals. Some irregular poikilitic microcline masses, interpreted as replacement crystals, may be incipient phenocrysts.

|

| PHOTO 5. A typical exposure of rock of the Ash Mountain complex. Medium-grained quartz diorite cuts dark, fine-grained rock; gray, fine-grained rock cuts both. |

|

| PHOTO 6. An intrusion breccia of gray, fine-grained rock into dark, fine-grained rock of the Ash Mountain complex. |

|

| PHOTO 7. A swarm of inclusions in the Tokopah pluton. |

Giant Forest Pluton. The Giant Forest pluton is named from somewhat weathered exposures in Giant Forest. The freshest outcrops of this unit are found in roadcuts along the Generals Highway west of the Lodgepole Campground. This pluton is by far the most extensive in the area; it crops out over approximately 50 square miles in a broad, irregular, northwest-trending band.

The exposures are light gray to medium gray depending on the amount of dark minerals. About 5 to 10 per cent each of the subhedral to euhedral hornblende and subhedral biotite is the most characteristic feature of the rocks of this pluton. Biotite is generally more common, although the first impression from a typical hornblende-bearing specimen is that hornblende predominates, probably because of the prominence of the well-formed hornblende crystals.

The Giant Forest pluton ranges from quartz diorite to intermediate quartz monzonite, but is predominantly granodiorite (fig. 3). Hornblende is generally present, along with biotite, but locally only biotite is present. The most obvious variation from the typical hornblende-bearing granodiorite is the biotite granodiorite along the east margin of the largest roof pendant. Near the contact with the roof pendant, hornblende is absent, and large irregular microcline phenocrysts have formed. The variation may be due to reaction with the metamorphic rocks, or it could be a separate intrusion. No contact was seen with the more typical hornblende-bearing rocks, but a contact could be missed because access is difficult and the cover is extensive.

|

| PHOTO 8. Foliation in the Tokopah pluton. Inclusions are elongated and bent around the originally less plastic bodies. |

Coarse-grained biotite granite is found in the area mapped as Giant Forest pluton, south of Big Baldy and south of Switchback Peak. Further work would almost certainly disclose that the granite could be mapped as a separate pluton. The approximate area that contains the coarse-grained granite within the Giant Forest pluton is shown on the geologic map (p1. 1) by the symbol "ggr."

|

| PHOTO 9. Injection zone at the contact of the Giant Forest pluton with schist east of Hospital Rock camp. |

|

| PHOTO 10. Lit-par-lit injection of Giant Forest pluton material into schist with later pegmatite dike (beneath the hammer). |

The most common mineralogic variation within the rocks that are a definite mappable unit is the variation in the amount of microcline. The microcline commonly shows evidence of having replaced earlier formed plagioclase (photo 18). The common supposition that quartz monzonite has more quartz, fewer dark minerals, and more sodic plagioclase than quartz diorite is not readily demonstrable in the specimens studied from the Giant Forest pluton. The sporadic occurrence of microcline seems to be the governing factor in the determination of the names of the specimens studied. No systematic distribution of the various rock types was found, but microcline was somewhat more abundant in the eastern part of the mapped area.

Big Meadow Pluton. The Big Meadow pluton is named from outcrops around Big Meadow, and it crops out over approximately 25 square miles in an arcuate band extending from north of Big Meadow south and east to Twin Lakes. The pluton is distinguished by its medium grain size (4 to 5 mm) and its low color index relative to the Giant Forest pluton (fig. 3). Fresh specimens are light gray, and some specimens have a pinkish cast. The Big Meadow rocks, however, are easily recognized as a unit. The grain size varies somewhat, but the light color and the generally similar texture throughout gives the rock a homogeneous appearance.

The Big Meadow pluton contains rocks ranging from granodiorite to quartz monzonite and the average of the 13 modes determined (fig. 3) is a granodiorite near the boundary of the quartz monzonite field.

The difference in rock names for individual specimens is probably in part the result of the sporadic occurrence of late microcline. The dark mineral content is fairly constant and the plagioclase has essentially the same anorthite content throughout the body.

Weaver Lake Quartz Monzonite. The Weaver Lake quartz monzonite is named from exposures around Weaver Lake in the northeast part of the area. The largest mass crops out over about 12 square miles. Seven much smaller masses, probably satellitic to the large mass, are exposed around the periphery of the main mass. Exposures are notably light gray and the distinguishing features are the fine grain size and the low color index. The texture is xenomorphic granular and the grains average 1 to 2 mm. Biotite is sprinkled sparsely through the rock; hornblende is rare.

The Weaver Lake rocks are readily distinguishable from most of the other plutonic rocks, but are almost identical with some of the aplite. Some of the smaller masses may be aplite, but they do not generally have the distinctive sugary texture of the aplite dikes. The Weaver Lake quartz monzonite may have been the source for many of the satellitic dikes in the area.

Pear Lake Quartz Monzonite. The Pear Lake mass is well exposed around Pear Lake in the eastern part of the area. It is a light-colored, coarse-grained rock that contains prominent pink potash feldspar, as well as white calcic oligoclase, gray quartz, and a minor amount of biotite.

Certain resemblances are apparent between the Pear Lake quartz monzonite and the Lodgepole granite. Both are coarse grained and have essentially the same minerals in about the same proportions. The Pear Lake mass, however, contains pink potash feldspar instead of the pinkish gray to salmon colored potash feldspar in the Lodgepole pluton. Microcline is predominant in the Lodgepole granite and microcline microperthite predominates in the Pear Lake mass. Also the plagioclase is slightly more calcic in the Pear Lake mass. These minor differences may, however, be variations within a single intrusive unit.

Lodgepole Granite. The Lodgepole granite is named from the prominent exposures near the Lodgepole Campground. The granite crops out over about 7 square miles in an elongate body extending from Little Lake to south of Panther Peak. In addition, two small masses intrude the Giant Forest pluton, north of Heather Lake.

|

| PHOTO 11. Prominent joint system near Emerald Lake. |

|

| PHOTO 12. Giant Forest plutonic rock invading hornfels and schist, yielding a vein-like pattern and many xenoliths. |

The distinguishing features of the granite are the coarse grain size, the seriate texture, and the distinct color difference of the two feldspars. The grain size ranges on the average from 5 to 10 mm but commonly grains as large as 15 mm and rarely as large as 25 mm are found. Locally gray quartz forms glomerophenocrysts as large as 25 mm across. The potash feldspar is pinkish gray to salmon colored and the sodic oligoclase is gray to white.

The contact with the Giant Forest pluton is generally sharp, but near the south end of the Lodgepole granite mass, scattered outcrops contain gradational types between the two varieties, suggesting that at least locally there is a mixed zone between them. This may be the result of mixing along the contact where local mushy spots were present in the Giant Forest pluton at the time of the Lodgepole granite intrusion.

Big Baldy Granite. The Big Baldy mass is named for Big Baldy, the highest point on a prominent ridge in the northwest part of the area. The granite is exposed over an area of about 4 square miles and is bounded on the east and west by metamorphic rocks. It is medium grained, contains small amounts of dark minerals, and is sparsely porphyritic with potash feldspar phenocrysts. It may be in part correlative with the Cactus Point granite.

In most of the specimens, potash feldspar makes up about half of the rock, and oligoclase and quartz each make up about a quarter of the rock; small amounts of biotite and hornblende also are present. In one specimen the usual plagioclase potash feldspar ratio was reversed, but this may be the result of an unrepresentative sample because of the small size of the thin section.

Cactus Point Granite. An area of about 5 square miles around Cactus Point, a small knob northeast of the Ash Mountain Park Headquarters, is composed of granite that is commonly light gray on fresh exposures, but fresh exposures are rare; the weathered rock commonly has a yellowish tint. A distinctive weathering feature of the granite is the iron-stain halo around biotite and magnetite, which gives the weathered rock a mottled appearance.

Two different types of granite appear to be present within the mapped area. Near the Ash Mountain Park Headquarters, and west of the mapped area, the granite is medium-coarse-grained and contains red-brown biotite and scattered pink garnet crystals; northeast of the Headquarters, the granite is fine-medium-grained, and contains traces of hornblende. The two varieties may be separable, but brush cover precludes detailed study in this part of the area.

Alaskite. Five small alaskite bodies crop out in the northern part of the area, which in aggregate cover about 2 square miles. The alaskite, seen from a distance, appears light gray to white on fresh surfaces; but on close observation it is seen to be cream-colored. The even, medium-grained texture, and an almost complete lack of dark minerals makes this a readily mappable unit. Small shiny grains of magnetite are particularly noticeable, probably because of the paucity of other dark constituents.

|

| PHOTO 13. Layered concentrations of hornblende in the Giant Forest pluton near Pear Lake. |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

ca/cdm-sr-53/sec3a.htm

Last Updated: 18-Jan-2007