|

California Division of Mines and Geology

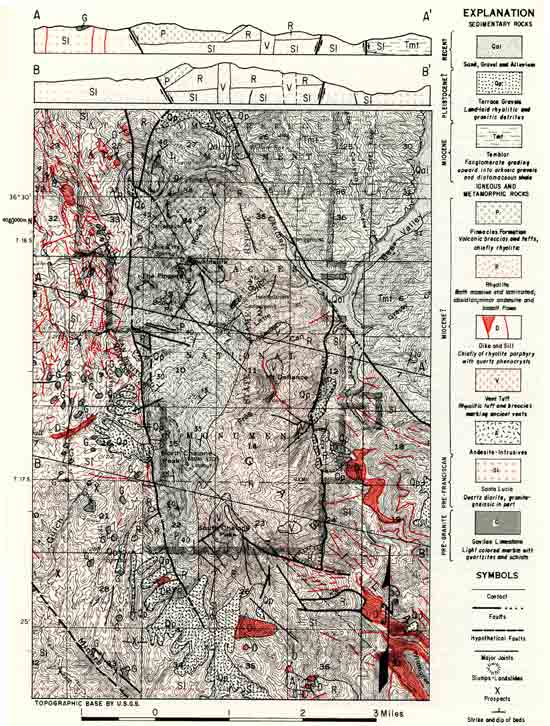

Mineral Information Service — Volume 21, Number 8 Geology and Road Log of Pinnacles National Monument |

GEOLOGY AND ROAD LOG OF

PINNACLES NATIONAL MONUMENT

The following material is taken from the Division's Bulletin 158, Evolution of the California landscape, by the late Norman E. A. Hinds. Unfortunately, the bulletin is out of print, and there is no immediate prospect of funds for reprinting it.

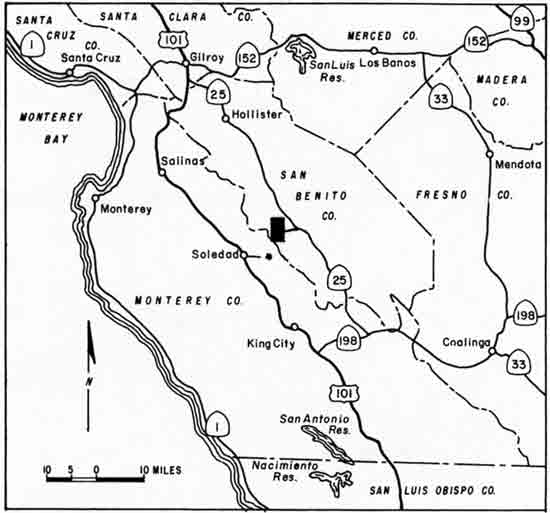

Pinnacles National Monument is between Salinas and San Benito valleys in the Gabilan Mountains, a division of the California Coast Ranges. It is 35 miles south of Hollister and about an equal distance north of King City. The area, because of its remarkable topography, was set apart as a National Monument by President Theodore Roosevelt in 1908 and has been considerably added to since that time. The monument is most accessible from the eastern side by a branch of a road leading south from Hollister. Good trails have been constructed so that the principal scenic features are within reach of hikers.

As the name suggests, the monument is an astonishing galaxy of rocky crags, spires, and pinnacles which make a most bizarre landscape.

The area is not particularly high. Chalone Valley has an elevation of about 1,000 feet, while nearby North Chalone Peak, highest point in the monument, stands 3,297 feet above sea level. Hawkins Peak, a spectacular assemblage of pinnacles, is more than 2,600 feet high.

|

| Map showing location of Pinnacles National Monument. |

Millions of years ago, this section of California was a vigorous volcanic field. Many lava flows were erupted and still greater thicknesses of exploded products were cemented together into volcanic breccias. In the breccias the principal erosional features were sculptured after the rock had been broken by great numbers of prominent joints. Weathering along these fractures loosened fragments which have been removed by gravity and running water, perhaps a minor number by wind, thus enlarging the joints and evolving a weird complex of land forms. Deposition of silica from water migrating through the breccias has greatly hardened certain parts, allowing them to stand out from adjacent more easily erodible material. The lava flows also have been abundantly jointed in places so that they have behaved much like the fragmental deposits in the formation of pinnacles.

Natural caves of rather large size are present along both branches of Chalone Creek, principal stream of the monument, which has undercut beds of massive breccia. In scouring out less resistant material, the excavation has been so extensive in places that large, unsupported masses have slumped down. A short distance from the Pinnacles Ranger Station, a subterranean chamber nearly 100 feet across and in total darkness except when artificially illuminated, has been formed by a single block of massive breccia supported around the edges by smaller blocks. Large joint blocks also have rolled down the steep canyon slopes aiding the formation of the caverns.

Except for Chalone Creek, streams flow through the monument only during and after heavy rains. The distinctly arid climate helps to preserve the angular outlines of the landscape and prevents the formation of a heavy soil cover.

Prior to the beginning of the volcanic episode, long erosion had reduced this section of California to a lowland of very subdued relief etched in various kinds of rocks with granite being the chief type in the monument. The resistant granitic basement was broken by numerous fractures probably during a later deformation and along these rose masses of rhyolitic magma which solidified as sills and dikes, some of which were undoubtedly feeders for the flows that poured out on the surface. The earliest surface eruptions were rhyolite flows which piled one upon another in considerable thickness, though somewhat later andesitic and basaltic magmas also were poured out. In the last stages of this flow episode, the lava apparently became quite viscous and a large, steep-sided mass was elevated along one of the fractures forming a volcanic dome having an elongate pattern contrasting with the more or less nearly circular examples in Lassen Volcanic National Park, Mount Shasta, and the Mono Craters on the east side of the Sierra Nevada.

Then from five nearly circular vents and possibly more, explosive eruptions blasted out great quantities of solid and liquid fragments. The largest center was that of South Chalone; the others definitely known follow a roughly north trend. The centers can be identified because explosions filled them with layered masses of rhyolitic tuff while round about is massive rhyolite. In these vent-fillings, as they are called, conical pinnacles have been carved by erosion.

The eruptions occurred during Miocene time, the fourth epoch of the Cenozoic era, consequently much evidence regarding them has been destroyed by erosion. Probably the massive breccia deposits were formed by several agencies including various types of violent volcanic explosion and the crumbling of the walls of the steep rhyolitic dome which formed a deep mantle of talus. Many flows followed explosive eruptions, enveloping great quantities of fragments and cementing them together. Other flows broke into brecciated masses as they advanced. Avalanches and the natural angles of repose of this coarse material maintained the steep slopes of the dome ridge.

The length of the volcanic episode cannot be estimated, but it must have been long, as more than 4,500 feet of fragmental debris is left and in addition a considerable thickness of lava flows. In addition, both explosive and flow eruptions were repeated after interruptions of various lengths during which volcanic activity virtually ceased and weathering and erosion of the volcanic deposits took place.

Faulting that occurred after the close of the volcanic cycle displaced rocks along the fractures considerably. Three principal faults are present in the Pinnacles National Monument, all of them being roughly parallel to the San Andreas fault which lies a few miles to the west. Erosion has removed volcanic rock from areas elevated along the fractures so that the original extent of the deposits cannot be determined, but it certainly has been considerably reduced. In quite late time the elevation of the region has caused conspicuous erosion by invigorated drainage.

ROADLOG

The following road log is taken (in altered form) from Guidebook to the Gabilan Range and adjacent San Andreas fault, published by the Pacific Section, American Association of Petroleum Geologists. For those who would like trips in this central California area, the Guidebook is a helpful tool. Price is $10, available from either Richard E. Anderson, Anderson & Nicholeris, 1336 Callens Road, Ventura, California 93303, or Willis R. Brown, Buttes Gas & Oil Co., 3132 18th St., Bakersfield, California 93301.

| Miles | ||

| 0.0 | (0.0) |

Start at intersection of California 25 and entrance road to Pinnacles National Monument. The first man who left a record of his visit to the Pinnacles area with its spectacular scenery was Captain George Vancouver, who passed this way in November of 1794. "On one side," he wrote, "it presented the appearance of a sumptuous edifice fallen into decay; the columns, which looked as if they had been raised with much labour and industry, were of great magnitude, seemed to be of an excellent form, and seem to be composed of . . . cream coloured stone." The picturesque jagged peaks which he discovered have occasionally been called "Vancouver's Pinnacles." A notorious bandit, Tiburcio Vasquez, used the rugged crags and intricate caves of the Pinnacles area as a hideout in the latter port of the nineteenth century before he was finally brought to justice. |

| 0.9 | (0.9) |

To right, outcrops of unconsolidated sand and gravel. This is shown by Philip Andrews on the map published in 1936 as Miocene fanglomerate containing minor amounts of diatomaceous shale. Note well-bedded nature of sediments. |

| 2.2 | (1.3) |

Miocene arkose on right. |

| 3.0 | (0.8) |

Note (at one o'clock) excellent view of the rugged skyline of the Pinnacles. The cliffs and spire-like columns of the Pinnacles rise to heights of 600 to 1,000 feet. In the steep narrow stream canyons beneath the Pinnacles numerous caves and subterranean passages are formed between the massive talus blocks derived from the cliffs above. There are natural caves also due to differential erosion of less resistant beds. One such subterranean room measures 100 feet across. These spectacular cliffs have been formed by weathering and erosion of a crudely bedded pyroclastic unit which dips west (away from us) and overlies an older rhyolite unit. This upper pyroclastic unit has been named the Pinnacles Formation. It consists of volcanic breccia, agglomerate, and tuff of rhyolitic composition. The underlying rhyolite has no name; it is composed mostly of massive rhyolite and obsidian intrusives and flows, including minor amounts of andesite and some basalt flows. These volcanic rocks are considered to be Miocene in age. Just to the north, in the San Benito quadrangle, the Pinnacles Formation is overlain by upper Miocene and possibly middle Miocene shale. If these volcanic rocks are correlated farther to the north with volcanic rocks in the San Juan Bautista quadrangle (which overlie sandstone of Zemorrion and Saucesian(?) age) a lower age limit can be indirectly established. G. H. Curtis, University of California at Berkeley, has obtained a preliminary potassium-argon age date of 22 million years for the Pinnacles Formation. |

| 3.3 | (0.3) |

Entrance to Pinnacles National Monument. |

| 3.5 | (0.2) |

Up hill on right is bold outcrop of rhyolite. |

| 3.7 | (0.2) |

Entrance station — Pinnacles National Monument. Beyond this point, rhyolite crops out across canyon to left. |

| 3.9 | (0.2) |

Turn left at fork toward Visitor's Center. Shortly after turn the road crosses the West Fork of Chalone Creek. |

| 4.0 | (0.1) |

Steep cliffs on the right are composed of jointed rhyolite. Jointing is very well developed locally. Note some small faults. Across canyon to left, rhyolite forms bold outcrops on lower slopes and soft Miocene arkose weathers to "badlands" in outcrops on higher slopes. The Chalone Creek fault separates the arkose from the rhyolite. |

| 4.2 | (0.2) |

Road bends to the right. Note continuing excellent outcrops of rhyolite on the right. On close inspection a persistent fine lamination can be seen in the rhyolite. Also note the close jointing and reddish color (perhaps in part a stain). On left across canyon note outcrops of the same rhyolite. This drainage is called Bear Gulch. Within the rhyolite to the south (hidden from view) Andrews (1936) maps several roughly circular masses of volcanic tuff within nonfragmental rhyolite. He interprets these as volcanic vents. |

| 4.4 | (0.2) |

Road bends to right. Note ahead the rugged skyline formed by erosion of the Pinnacles Formation. Note the massive irregular columns, spires, crags, and cliffs. |

| 4.9 | (0.5) |

Headquarters area of the park. |

| 5.0 | (0.1) |

Turn off to left for parking area, museum, and information building of Pinnacles National Monument. Note outcrop on right of green and red colored finely laminated rhyolite. |

| 5.3 | (0.3) |

Bear Gulch picnic area. Several foot trails start from this area and climb up to the north into the Pinnacles Rocks, and to the south to Chalone Peak. Excellent view ahead and straight up of precipitous cliffs in red Pinnacles Formation mottled green and brown by lichens. Note contact at base of red cliff between Pinnacles Formation and underlying rhyolite unit which forms more subdued brown to gray outcrops. To the west of this point approximately 1-1/2 miles, these volcanic rocks are abruptly terminated by a fault which trends north-south and is known as the Pinnacles fault. To the west of this fault granitic rocks of the Gabilan Range are present, intruded by numerous dikes of rhyolite porphyry, dacite and andesite. The bulk of these Miocene volcanic rocks are contained in a graben structure between the Pinnacles fault on the west and the previously mentioned Chalone Creek fault on the east. Return via same road to California 25. |

REFERENCES

Andrews, Philip. 1936. Geology of the Pinnacles National Monument [Monterey and San Benito Counties, California]: University of California, Department of Geological Sciences Bulletin, vol. 24, pp. 1-38, 2 pls., 11 figs., map. (Out of print.)

Hinds, Norman E. A. 1952. Evolution of the California landscape: California Division of Mines Bulletin 158, pp. 180-181. (Out of print.)

Rogers, T. H., Gribi, E. A., Jr., Thorup, R. R., and Nason, R. D. 1967. Guidebook. Gabilan Range and adjacent San Andreas fault. American Association of Petroleum Geologists, Pacific Section. Pp. 30-32. [Processed.]

|

| Pinnacles (Hill photo) |

state/ca/mis-21-8/sec1.htm

Last Updated: 23-Nov-2012