|

The Geologic History of the Diamond Lake Area

|

|

GEOLOGIC HISTORY OF THE DIAMOND LAKE AREA (continued)

GLACIATION OF THE ICE AGE

Approximately one million years ago, at the close of the Pliocene, the Great Ice Age descended on the area. The alternate advances and retreats of ice and snow lasted until a scant 10,000 years ago.

As the Ice Age crept upon the area, the winter snows high on the slopes of Mt. Bailey and Mt. Thielsen remained a little longer each spring. The climate grew gradually cooler, and soon the snows did not melt during the summer, but remained to be buried by the next winter's snows. In this manner, ice and snow began to accumulate on the higher peaks in the Diamond Lake area. The weight of new snow compacted the old, producing dense granular, glacier ice. The dense ice flowed imperceptibly down the flanks of the mountains—the glaciers were advancing over the landscape.

The volcanic peaks in the Diamond Lake area became inactive about the time glaciers began to form on them. The peaks were thus unable to resist the attack of glacial erosion. Younger High Cascade peaks, such as Mt. Mazama some 15 miles to the south of Mt. Bailey and Mt. Thielsen, continued to expel lavas and grow in stature, despite the erosive effects of the glaciers. Striations left on the rocks high on Mt. Mazama indicate glaciers once crept down the sides of the mountain. The striated lavas are overlapped by younger flows, indicating the volcano continued to spew out lava throughout and after the period of glaciation. Mt. Mazama retained its conical form despite extensive glaciation.

Meanwhile, the glaciers began to gouge at the sides of the extinct volcanoes in the Diamond Lake area. Glaciers crept radially away from the higher peaks such as Mt. Bailey, Mt. Thielsen, and Howlock Mountain. The flanks of the defenseless mountains were hollowed out in great scoops, forming cirques. The ice creeping down the east slope of Mt. Bailey merged with the glaciers flowing down the west slope of Mt. Thielsen. These were joined from the south by a large glacier whose head was high on Mt. Mazama. The entire area now occupied by Diamond Lake, the lower slopes of Mt. Bailey and Mt. Thielsen, and the area to the south of Diamond Lake were covered by a vast ice field.

|

| Diamond Lake and Mt. Bailey as seen from Mt. Thielsen. |

Several times during the Pleistocene the ice advanced and, by melting, retreated. Each time the ice melted, the ground-up rock powder it contained was washed downstream and deposited in layers or beds. These beds of glacial clay are impervious to water. As water from rain and melting snow percolates down through the younger soil and rocks above, and encounters the clay bed, it is unable to penetrate the clay layer and so moves downslope along the top of it. If the clay layer intersects the surface, the water seeps out at that point to form a spring. The numerous springs east of Lemolo Lake, including Crystal Springs and those feeding Spring River, originate in this manner.

The last advance of the glaciers was the most extensive. As the ice covering the valley between Mt. Bailey and Mt. Thielsen melted, it left behind a shallow lake. Diamond Lake measures about 3 miles by 1-3/4 miles, but is only slightly more than 50 feet deep. Melting glaciers furnished the water. The toe of a lava flow from Mt. Thielsen provided a low dam across the north end of the lake. The shallowness of the lake is governed by the elevation of its outlet, Lake Creek, which drains Diamond Lake at its northwest corner.

|

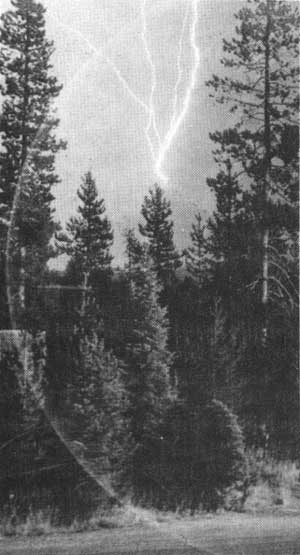

| Lightning strikes tip of Mt. Thielsen during night storm. |

After the last attack of the glaciers had subsided, the high peaks in the Diamond Lake area had changed shape. Mt. Bailey was no longer a symmetrical cone, but contained large cirques which exposed the layers of lava and cinders that the volcano had extruded near its summit. This mountain, however, was not as severely carved as Mt. Thielsen, which was initially much higher than Mt. Bailey. Glaciers had sculpted the top of Mt. Thielsen from all sides, producing a series of cirques whose edges widened until they met, thus forming long, sharp ridges extending radially from the mountain tops. These ridges are called arêtes. The soft cinder beds were more easily glaciated than the dense plugs occupying the vents of the volcano. The cirques that developed about the western plug left it standing steeply above the ridges and cirques below as a sharp pinnacle, or matterhorn. This spire is between 100 and 200 feet high and has given rise to the nickname which is applied to Mt. Thielsen, "The Matterhorn of the Cascades".

Mt. Thielsen also is called "The Lightning Rod of the Cascades", and with good reason. This peak is frequently struck by lightning, resulting in the creation of a geological oddity—fulgurites.

The name fulgurite is derived from the Latin for thunderbolt. Fulgurites are blebs, coatings, or tubes of bubbly glass, formed by the instantaneous fusion of rocks or sand when struck by lightning. The intense heat fuses the rock to a bubbly glass devoid of even the smallest crystals which generally are present in glassy volcanic rocks.

The fulgurites on Mt. Thielsen are splotches, or bubbly coatings, of brownish-green glass which resemble drops of paint spattered on a greasy surface. Occasionally the fulgurite takes the form of a glass-lined hole in the rock, less than an inch in diameter and tapering several inches into the interior of the rock. Such carrot-shaped forms are called "lightning tubes". The great majority of the fulgurites on Mt. Thielsen are confined to the uppermost 5 or 10 feet of the summit. Obviously, the top of Mt. Thielsen is an imprudent spot to select for sitting out a thunderstorm!

Fulgurites have been reported atop other sharp Cascade peaks, notably Union Peak.

Other peaks in the Diamond Lake area are more-or-less glacially carved, depending primarily upon their elevation. The size and thickness of glaciers on the lower peaks was insufficient to produce extensive glaciation.

The last melting of the glaciers, which occurred about 10,000 years ago, littered the slopes of the mountains with rock material varying in size from large boulders to fine dust. This material had been frozen in the glacier, and simply was dumped on the ground when the ice melted. Forests have re-established themselves on the mountain slopes, and at present the heavy forests and glacial debris obscure most of the lava flows on the lower slopes of the volcanoes in the Diamond Lake area.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

diamond_lake_geology/sec3b.htm

Last Updated: 01-Jul-2008