|

Grand Teton

A Place Called Jackson Hole A Historic Resource Study of Grand Teton National Park |

|

CHAPTER 13:

The Communities of Jackson Hole

A mass meeting is called for two o'clock Tuesday afternoon at the Jackson Club House to further discuss the subject of incorporating Jackson.... Ladies, as well as men, are requested to be present at this meeting let noone [sic] stay away.

—Jackson's Hole Courier, May 7, 1914

Death and destruction came down the Gros Ventre River yesterday morning in a great wall of water that snuffed out six lives, wiped the town of Kelly off the map....

—Jackson's Hole Courier, May 19, 1927

|

| Town of Jackson, 1907. William Trester, Jackson Hole Historical Society and Museum |

Between 1850 and 1900, thousands of small towns developed west of the Mississippi River, playing an essential role in westward expansion. Economics drove people to develop communities. Entrepreneurs built businesses such as inns or blacksmith shops along transportation routes to cater to traffic. Townspeople also formed communities around stores and post offices to provide goods and services to farmers, ranchers, and miners. Finally towns resulted from pure speculation. Federal laws, notably the Townsite Act of 1844 and its more restrictive successor of 1867, gave promoters the means to secure land, luring hordes of speculators west. [1]

Small western towns, particularly agricultural communities, shared a sameness noticed by most observers. Surveyors laid out townsites in the familiar block pattern, making minimal concessions to topographic reality. Architectural patterns were also similar. The false front store became the dominant architectural style for main street buildings. Residences varied according to income. Modest homes followed standard patterns, while prefabricated homes could be ordered through mail order houses such as Montgomery Wards. Affluent people built substantial homes that reflected their economic status. These houses are popularly known as "Victorian," a general architectural term for styles that flourished between 1860 and 1915. Multiple stories, elaborate ornamentation, and a variety of colors and surface textures characterized Victorian residential architecture. Their sameness reflected the quest of migrants to create the familiar in an unfamiliar, sometimes hostile environment. [2]

Western communities also shared several common institutions. Indeed, towns buffeted by the boom-and-bust cycles of mining and agriculture depended on these institutions for survival. Local newspapers were key for they helped define the self-image of a community and "created the illusion of a homogenous society." Just as important, town newspapers promoted unabashedly the communities they served, often with little regard for truth. A second institution was the general mercantile store, the main source of supplies. Not only could patrons buy staple items such as flour, salt, sugar, and coffee, they could obtain luxury items such as gold watch chains or china dolls. The general store served as a social center where people congregated to share news and gossip. They also assumed the role of banks, extending credit and, if the store had a safe, securing checks and other valuables of customers.

A hotel was another important component of a frontier town. However crude the accommodations, a hotel boosted the self-esteem of a community. Saloons were an important place for entertainment and socializing. Alcohol provided a cure, however false, for the isolation and boredom that typified so much of life on the frontier. Education assumed more importance as westward expansion progressed through the nineteenth century. Westward migration weakened traditional institutions such as the family church, apprentice system, and folk traditions. [3] Frontier schools helped fill that void. Spiritual life remained important, and as communities matured, devout citizens built churches. As towns developed, townspeople also established specialized businesses such as drugstores, restaurants, and hardware stores. The blacksmith was the most needed craftsman, shoeing horses and performing essential repairs on tools, machinery and vehicles.

In Jackson Hole, towns and villages evolved slowly with the gradual increase in population. The first communities were rural post offices, sometimes augmented by country schools, churches, or perhaps a small boarding house. Jackson Hole was able to support only three towns: Jackson, Wilson, and Kelly—four, if Moran is counted. Towns were a twentieth-century development in the valley. Prior to 1900, it remained a sparsely populated backwater, a mosaic of isolated homesteads clustered in the Flat Creek area, South Park, and the Buffalo Fork. As more post offices and schools emerged after 1900, settlers developed a sense of loyalty or identity to their locality rather than the town of Jackson or Jackson Hole. One settler recalled that "the valley was divided into three or four parts. There was Moran and Elk in the upper end, Grovont and Kelly in the middle, then in the lower part there was Jackson and Wilson, with Zenith and Cheney scattered around." [4]

Potential towns such as Marysvale and Grand Teton never progressed beyond wishful thinking. On March 25, 1892, the Postal Service authorized the valley's first post office, Marysvale. Located at the Fred White homestead north of Botcher Hill, the post office was named for White's wife, Mary. The Whites managed the post office until 1894, when they abandoned the "swamp ranch" for a more attractive homestead along the Snake River. William and Maggie Simpson took over the post office, which was renamed Jackson. In 1896, the Wyoming Tribune reported that promoters were staking out the city of Grand Teton, anticipating a population boom in the coming summer. The proposed townsite was located at the north end of Spring Gulch, one-half mile from the hot springs near East Gros Ventre Butte. The city of Grand Teton existed only in the newspaper article and imaginations of its promoters, for no lands were preempted nor a townsite staked out by surveyors. [5]

A small village evolved around the Jackson Post Office. Charles "Pap" Deloney opened a general store on the Simpson ranch, the first retail store of any kind in Jackson Hole. Deloney's consisted of the store, a barn for building materials, and a small storage cabin. Like most general mercantile stores, Deloney sold an amazing variety of goods; half of the store housed groceries and hardware while the other half displayed dry goods such as clothing and sewing machines. Glass, window and door frames, lumber, and farm machinery were kept in the barn. Around 1897, members of the Jackson Hole Gun Club built the Clubhouse, Jackson's first community building. A two-story rectangular frame building with a hipped roof, it served as a dance hall, courtroom, men's smoking room, gymnasium, and commercial building. Prior to 1900, Mary Anderson established what may have been the first hotel or boarding house in the valley near Antelope Gap or the wye. Mrs. Anderson became the postmaster of Jackson in 1900. The hotel was moved to the townsite of Jackson in 1901, where it became known as the Jackson Hotel. The seeds of the community were sown when Bill Simpson laid out the first town plat for Jackson in 1901. [6]

|

| The Jackson Hole Gun Club was built in 1897. Known as the "Clubhouse," the gun club was the town's first community building and was used for a variety of social functions. Although modified, the building still stands on the Jackson Town Square. Jackson Hole Historical Society and Museum |

Between 1901 and 1914, Jackson established itself as the valley's primary community. Citizens started the first town school in the Clubhouse in 1903, then built a log school in 1905. In the same year, Mormons constructed the town's first church, a brick building situated on the western fringe of the village. The bricks were manufactured at a kiln located near the wye, owned by two men named Parker and Mullen. Workers enclosed the Jackson Hotel in brick and added a two-story brick wing to the rear of the building. In 1906, Frank and Roy Van Vleck rolled into Jackson driving a wagon loaded with either potatoes or apples, depending upon which account is read. A sick horse prevented them from going on to Oregon. The brothers opened the Jackson Mercantile, selling their load of produce to raise capital. [7]

William Trester took the earliest known photograph of Jackson in 1907. From the east slope of East Gros Ventre Butte, his camera captured a sleepy frontier village on a sunny spring afternoon. The photograph shows a collection of buildings spread across the sagebrush flat. Recognizable structures include the Mormon Church, the Clubhouse, and the Jackson Hotel. Less recognizable are Tuttle and Lloyd's Saloon, Deloney's store, and Wort's livery barn. Willows reveal the course of Cache Creek east of the village. Before the Clubhouse is a large sage brush swale, rutted by two sets of wagon tracks. This eventually became the town square. [8]

Following the pattern of other frontier towns, more entrepreneurs started specialized businesses. Sometime after Trester's photograph, Dr. Luther F. Palmer constructed a two-story frame building on the southeast corner of the square, intending to use it as a residence and sanitarium. Convalescent homes were not uncommon in the West, as people with asthma and tuberculosis often relocated to the West for the dry desert air or mountain climate. In 1908, Palmer sold the building to Claude and Maud Reed, who converted it to Jackson's second hotel. Ma Reed's, later the Crabtree Inn, became a local landmark until 1952 when the Crabtrees sold it. [9]

In 1909, Jackson reached another milestone, when Douglas Rodeback published the first edition of the Jackson's Hole Courier. The paper gave the village an important voice in promotion, and articulated and helped define the community's self-image. [10] By this time, Jackson claimed a population of 200 people and had established itself as the commercial center of Jackson Hole. E. C. "Doc" Steele opened a drugstore, L. H. Zimmerman started a butcher shop in 1914, and Fred Lovejoy brought a touch of modernity by building a telephone exchange in 1905. [11]

|

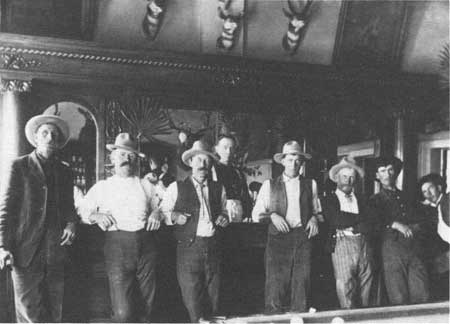

| The Rube Tuttle saloon was a popular gathering place in Jackson. Lined up at the bar are (left to right): S. L. Spicer, Rube Tuttle, Willard Miner Sr., T. Lloyd (behind bar), Walt Spicer, Frank La Shaw, Jack Grey, and Alva Simpson. Jackson Hole Historical Society and Museum |

In 1912, the Episcopal Church established a mission in Jackson. Members built a rest house in 1912-1913, which eventually included a gymnasium, library, and reading room. The Jackson school district built a two-story brick schoolhouse, which opened in 1914. A year later, on December 10, 1915, fire destroyed both the new brick school and the first log schoolhouse. The valley's first bank opened in August 1914. Located in a small brick building south of the Jackson Hotel, the Jackson State Bank marshaled $10,000 in capital, providing a local source of funding for community development. [12] In the spring of 1914, the citizens of Jackson began considering filing articles of incorporation for town government. Talk became reality, and the townspeople elected a mayor and town council in November 1914. [13]

In retrospect, it is apparent that Jackson enjoyed an advantage over its early potential rivals Wilson and Moran. Because of its central location between clusters of homesteads in South Park and the Flat Creek area, Jackson possessed a geographic advantage and established a more solid economic base than either Wilson or Moran. Most homesteads were situated east of the Snake River, which negated Wilson's prime location on the road over Teton Pass. At the north end of the valley Moran was far too isolated, even after the Reclamation Service developed the Ashton-Moran Road in 1910. Struthers Burt recalled that "as winter draws down in a frontier country the principal town becomes the focus of the community." To enable children to attend school, families often relocated to town from isolated ranches, joining unemployed ranch hands holed up in hotels and boarding houses. [14]

Between 1915 and the depression of 1929, Jackson experienced prosperity fueled by high prices for agricultural products and a population increase. More businesses located in the community and modern conveniences transformed the village to a twentieth-century town. In 1918, the Kemmerer Camera portrayed Jackson as a bustling little community consisting of a bank, a telephone exchange, a drugstore, the Elk Cigar Store, a billiard parlor, two hotels, and two general mercantile stores. [15]

Important modern improvements included the installation of electric power and water and sewer systems. In 1920, E. C. Benson constructed a water-powered plant at the mouth of the canyon on Flat Creek, north of Jackson. In the last week of January 1921, electricity from the plant illuminated Jackson for the first time. At least one resident expressed skepticism about the project. Bill Blackburn informed Benson that the electric plant would never work, since "there wasn't a hole in the wire for the electricity to run through." After Benson's plant illuminated the town, Blackburn was chagrined, but undaunted. He decided that if the electric company could make electricity go through solid wire, he could do it too. Blackburn bought cheap wire, secured a 12-volt auto light, and wired his cabin. He threw loose wire over a 120-volt power line tying wires together. The next day Blackburn confronted Benson with a consumer complaint: "Your juice is no good. It is too hot. It set my house on fire." By 1919, the town government had installed water and sewer lines. In 1916, St. John's Hospital was built with private subscriptions and Episcopal mission funds. [16]

The first edition of the Courier in 1921 listed the following businesses and services: the Jackson Mercantile—furniture and hardware; the Jackson Drug Company; Vincent the Tailor—Clothing; R. E. Miller's bank; the J. R. Jones Grocery; William Mercill's Grocery; Harry Wagner—Insurance; the Jackson Valley Telephone Company; the Jackson Billiard Hall; Fuller and Kent's Billiard Hall; the Picture Show, a movie theatre; the Jackson Laundry; the Jackson Leather Shop; Brown and Woods Blacksmith Shop; the two hotels; and the Spicer and Curtis Garage. A June issue listed additional businesses: Deloney's General Store; Charles Fox—Lumber; George Blair's taxidermy shop; the Jackson Meat Market; two barber shops, Mulherns and Fullers; and Wort's livery barn. [17]

Doctors were significant members of any community. In the absence of doctors, settlers relied on their own knowledge to treat injuries and sickness. Several pioneer women were midwives and known for their "doctoring" skills. They included Mary Wilson, Matilda Wilson, Mrs. H. M. Ely, Mrs. C. J. Allen, and Mrs. Sam Osborne. The valley may have had a physician prior to 1900. According to local tradition, a Dr. Woodburn practiced medicine in the valley in 1894, living in the Carnes cabin on Flat Creek. Others remembered a doctor named Reece or Reese. Dr. Luther F. Palmer was the first physician known to reside and practice medicine in the valley. Listed in the census of 1900; Palmer treated people during a diphtheria epidemic in 1902, and the first Courier reported that a Dr. Louis [sic] Palmer treated a patient for blood poisoning in January 1909. At Moran, the Reclamation Service employed several physicians during the construction of the Jackson Lake Dam. Horace Carncross served as resident physician at the JY Dude Ranch and later at the Bar BC. When present in the valley he also treated residents. [18]

In January 1913, a 24-year old doctor named Charles W. Huff set up a practice in Jackson. Huff had developed symptoms of tuberculosis and had been advised to locate in a mountain climate; he also learned that Jackson had no doctor at the time. He practiced medicine until his premature death in 1937, giving Jackson Hole people over 20 years of stable medical care. Aware of preventive medical techniques, Huff lobbied actively for water and sewer systems and was a driving force behind the construction of Jackson's first hospital in 1916. After his death, Dr. Don MacLeod replaced him. [19]

In 1915, Dr. C. S. Horel set up the first known dental practice in the valley. Initially he set up office in front of the local taxidermy shop, but later thought better of it and moved the office to his residence. Horel practiced part time. He homesteaded near Menor's Ferry, then later secured a job as a ranger with the Forest Service. At the end of 1914, A. C. McKahan set up a veterinary practice, working out of Wort's livery barn. [20]

In 1920, a local political caucus nominated an all-women's ticket to run for mayor and four town council seats. The editor of the Courier wrote "if elected this next Tuesday this capable women's ticket will place the city of Jackson in the limelight." On May 11, the voters elected the entire ticket, and they took office on June 7.

Election Results

Mayor

Grace Miller

Fred Lovejoy56

28Town Council—2 year term

Rose Crabtree

Mae Deloney

William Mercill

Henry Crabtree50

49

34

31Town Council—1 year term

Genevieve Van Vleck

Faustina Haight

Maurice Williams

J. H. Baxter53

51

31

28

|

| In 1920, the Town of Jackson elected the first all-female government in the country. Left to right: Councilwoman Mae Deloney, Councilwoman Rose Crabtree, Mayor Grace Miller, Council woman Faustina Haight, and Councilwoman Genevieve Van Vleck. Jackson Hole Historical Society and Museum |

Jackson voters made history by electing the first all-female civic government in the United States. In addition, schoolteacher Pearl Williams served as town marshal for a year. In 1921, Mayor Grace Miller and one-year incumbents, Genevieve Van Vleck and Faustina Haight, were reelected. [21]

Public parks and events reflected civic pride and a sense of community. Several Jackson Hole pioneers conceived the idea of a rodeo in Jackson. Frontier Days; as it was named, became the valley's first local celebration. Sponsors built a grandstand in a field southwest of Jackson and held the event in 1912. Bell Flanders, a sister of the Worts, owned the land. She donated 45 acres to the town for Frontier Park in 1920. However, the most notable landmark in Jackson is Town Square, a picturesque park of cottonwoods, post-and-pole fence, boardwalks, monuments, and distinctive elk antler arches on each corner. In the beginning, the square was nothing more than a sagebrush-covered depression surrounded by dirt roads and buildings. In 1924, the town government planned to improve the square and fill material was to be hauled in to level the site. But not until 1931 did a citizens group improve the square. To commemorate the 200th anniversary of George Washington's birth, citizens raised money for nursery plants and landscaping and named the improved square Washington Memorial Park. In 1941, the town announced plans to pave the streets around the square, eliminating the dust and mud problems. [22]

The automobile and the growth of tourism changed Jackson from a frontier community to a modern town. Like other American communities, the dogma of progress conflicted with the urge to preserve the familiar or "keep things the way they are." In 1931; for example; Fred Lovejoy constructed a log building, a "real frontier cabin" more compatible with the image the town sought to cultivate. In reality, frame and brick buildings dominated the town. One year later, Bruce Porter installed a neon sign at the Jackson Drug, the first in the valley. In September 1941, Jess and John Wort opened a new hotel, described as Jackson's first frilly modern hotel. The Wort has since become a local landmark. [23]

By the early 1920s, Jackson had consolidated its position as the economic and social center of the valley. After the creation of Teton County and the resolution of prolonged litigation over its establishment, Jackson became the new county seat by a surprisingly close vote. As the county seat, Jackson became the political center of Jackson Hole. [24]

|

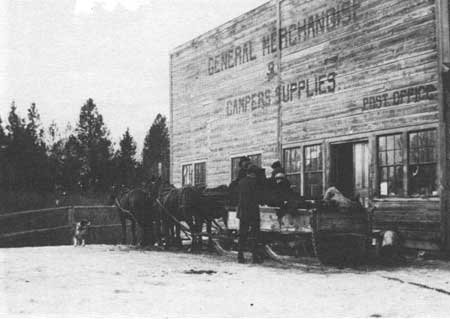

| False-front buildings, such as the Wilson General Store, were a common architectural style in Jackson Hole. Jackson Hole Historical Society and Museum |

One community that might have rivaled Jackson was Wilson. Named for pioneer Uncle Nick Wilson and his family Wilson straddled the eastern end of the Teton Pass road at Fish Creek. The village had its beginning when Nick Wilson homesteaded at the eastern base of Teton Pass in 1889. The Wilsons were in a good position to provide food and lodging to travelers, situated on the main route into Jackson Hole. Wilson and his son-in-law Abe Ward built a hotel, store, and saloon in 1898. Further, the Postal Service established the Wilson Post Office on January 10, 1898. Matilda Wilson served as the first postmaster until 1899; her husband, Nick Wilson, worked as postmaster from 1899 through 1902. The first school in Wilson was held in one room of the Nick Wilson residence in 1898. By 1900, residents had formed a school district. The January 28, 1909, issue of the Courier listed several businesses at or near Wilson: the Wilson Hotel; a feed and livery; Roy B. Anderson, General Merchandise—Clothing and Groceries; and three sawmills, the Johnson Brothers Lumber, Kaufman and Barker, and Schofield and Van Winkle. The Courier published a Wilson news column. Nevertheless, Walt Callahan, as a boy in 1917, recalled Wilson as "just a wide place in the road." By 1918, Robert Lundy operated a store, which became an important institution in the community. In 1925, Wilson consisted of a general store, a garage, a blacksmith shop, and a livery stable and had a population of 50 people.

Wilson never competed seriously with Jackson, even though it had more direct access to supply and communication links with Idaho. Because of its location, Wilson was not conveniently situated as a commercial center for homesteaders; most lived east of the Snake River. The river posed another problem as Wilson was and remains vulnerable to flooding. The flood of 1915 and the Kelly flood of 1927 inundated the village. Finally Wilson residents did not seem to promote their community as aggressively as the citizens of Jackson, who secured a newspaper and a bank, and incorporated in 1914. [25]

One man was most responsible for the emergence of Moran—Ben D. Sheffield. In 1903, Sheffield bought the property of two homesteaders—Frank Lovell and Ed "Cap" Smith—and built the headquarters for a hunting and outfitting business at the outlet of Jackson Lake. In creating the Teton Lodge Resort, Sheffield and his wife had formed a partnership with Marion Lambert, a wealthy Easterner. Situated in a prime location, Moran captured the business of travelers to Yellowstone, Jackson, Ashton, or Lander. Moran also became the first "tourist town" in Jackson Hole, in that catering to travelers and hunters formed the economic foundation of the village.

|

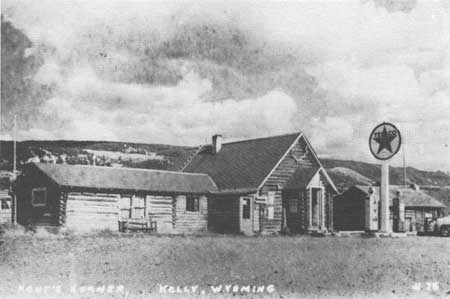

| Kent's Korner store in Kelly. Jackson Hole Historical Society and Museum |

Prior to Sheffield's arrival, Cap and Clara Smith had constructed the large log hotel described in previous chapters. The hotel probably burned sometime after November 1900. Near the Smith Hotel, C. J. and Maria Allen homesteaded land west of Oxbow Bend in 1897. After the Smith Hotel burned, the Allens built the Elkhorn Hotel. The log hotel included a dining room, saloon, and livery stable. Nearby W. C. Deloney opened a general store. Either Frank Lovell or Sheffield built a toll bridge at Moran, which became an important transportation link in the valley. Moran had received its name when Maria Allen opened the post office in 1902. In 1907, Sheffield took over the Moran Post Office, which he operated until 1919. Moran became the valley's only government town during the construction of the Jackson Lake Dam from 1910 to 1916. The Reclamation Service built an entire camp replete with barracks, mess hail, a commissary offices, warehouses, and a hospital in the flats north of Sheffield's. [26]

By the late 1920s, Sheffield's Teton Lodge consisted of a large central lodge surrounded by log guest cottages, capable of accommodating 125 guests. The Sheffields sold out to the Snake River Land Company in 1929. This company turned the complex over to the Teton Investment Company, which operated the lodge. The main lodge burned in 1935. A 1946 site map shows an extensive complex consisting of 113 structures. In the 1950s, the Grand Teton Lodge Company and the National Park Service phased out the operation, and the buildings were removed by 1959. Many cabins were moved to Colter Bay. [27]

The town of Kelly developed later than Moran or Wilson, but emerged as a bustling community that appeared for a time to rival Jackson politically and commercially. Prior to its designation as a post office, settlers referred to the Kelly area as the "Bridge." Around the turn of the century, local residents had constructed a timber bridge across the Gros Ventre River which became an important crossing. By 1909, a school had also been built in the vicinity. Norman Smith's wife and children spent three winters at Kelly so his youngsters could attend school, while he remained at his homestead at Blacktail Butte. In April 1914, the Courier reported that the Smith family had returned to their homestead after spending the winter at the "Bridge." The following September, local farmers and ranchers had built four new houses on the W. J. Kelly property, so their children could also attend school. In addition, a new school was being built in the emerging town. [28]

|

| In 1917, Milton Kneedy hauled flour mill equipment over Teton Pass, and installed it in his mill in Kelly. However, the flour mill was not a success, and the mill house burned in 1921. The man holding the reins in this photograph is Gerrit Hardeman; John Kneedy is standing next to the wagon. Jackson Hole Historical Society and Museum |

By 1914, several entrepreneurs had located businesses in the Kelly area. Among them were the Grovont Mercantile, the Riverside Hotel, and a blacksmith shop. In October, the Postal Service authorized a post office at Kelly. Ben F. Goe was the first postmaster. For a time, the community had a sawmill until it was purchased and the machinery removed in 1918. By 1921, pioneer Albert Nelson owned a feed stable and livery service at Kelly. At one time, the community also possessed a dance hall, which burned at an unknown date. [29]

Milton K. Kneedy constructed the most unique business in Jackson Hole in 1917-1919, a flour mill. A miller by trade, Kneedy determined to open a flour mill after testing wheat grown in Jackson Hole for suitability as flour. In March 1917, Kneedy purchased a 20-barrel-capacity flour mill, manufactured by the Midget Marvel Milling Company, along with a gristmill for producing livestock feed. In the fall, surveyor Otho Williams staked out a site for the mill; but the Kneedy Flour Mill did not produce flour until July 1919. In October, 1921, fire destroyed Kneedy's mill, as well as tons of flour and wheat, ending Jackson Hole's experiment in flour production. [30]

Kelly competed with Jackson for designation as the seat of Teton County in 1921. Unexpectedly proponents of Kelly garnered considerable support throughout the valley. Editorials in the Jackson's Hole Courier reveal a split in the community, characterized by a surprising level of acrimony. The editor of the Courier was caught in the middle as a booster of both valley and town. As the June election approached, rhetoric heated up in editorials and letters to the editor. Introducing more controversy a small but influential minority opposed the creation of Teton County. In May voters approved a county road bond by a vote of 326 to 26. However, 16 of the negative votes came from the Kelly district. A Courier editorial jabbed Kelly residents: "In view of the fact that Kelly is representing herself to be an up-to-date little village, and is bidding for the county seat, we are both surprised and disappointed at the 45-16 Kelly vote." Then, just prior to the election, the local newspaper published an editorial titled "Twelve Reasons Why County Seat Should be at Jackson," presenting both cogent and specious arguments for locating the seat in Jackson. Support for the creation of Teton County won by an overwhelming majority, but the county seat vote was surprisingly close. Jackson beat Kelly by 424 to 402. The vote indicated a distinct split among valley residents and some resentment toward the town of Jackson. The Kelly Wilson, and Teton precincts formed a substantial anti-Jackson block. The solid Jackson and Cheney vote, as well as the split vote at Elk, made the difference. Adding to the confusion and controversy 19 Alpine residents cast votes, even though this district was not part of the new county. Opponents in the Kelly area filed suit, seeking to block the creation of a new county, and the issue was only resolved in 1923 with new state legislation and a state supreme court decision affirming the creation of Teton County. [31]

Kelly survived political and legal defeat and, by 1926, had a population of 50 people, stores, a hotel, a garage, a blacksmith shop, a livery stable, telephone service, and daily mail delivery to the post office. A school and Episcopal Church were also located in the village. The town even had taxi service, provided by Walt Spicer who owned the garage. A year later, there would no longer be a village of Kelly. [32]

Kelly's death began on June 23, 1925, when a section of the north slope of Sheep Mountain slid into the canyon, damming the Gros Ventre River. An estimated 50,000,000 cubic yards of sandstone sheared off an underlying layer of shale, creating a dam 225 feet high and one-half mile wide. An unusual amount of precipitation may have caused the slide. Waters of the Gros Ventre backed up and flooded several homesteads and the Horsetail Creek Ranger Station. On July 9, the Courier reported water seeping through the dam; and by July 16 the water level was five feet below the dam. Engineers inspected the dam and declared it safe.

Two years later, the Gros Ventre River ran full, fed by snowmelt and heavy rains. On the night of May 17, 1927, water spilled over the dam. Charles Dibble, a U.S. Forest Service ranger, warned people in the area, but no one seemed unduly alarmed. By 1:00 A.M., one bridge was gone. The next morning, the river had filled its channel. Dibble and several Kelly residents were knocking driftwood away from the village bridge when they saw heavier debris and a hayrack sweeping towards it. Becoming suspicious, Dibble and another man drove up the Gros Ventre Road to check the dam. Upstream from Kelly they encountered a wall of water roaring down the canyon. Dibble raced his Model T to a nearby house and asked the woman to raise the alarm downriver over the telephone. Speeding to Kelly he warned the residents, most of whom evacuated the town and school. The Kneedy family did not believe Dibble, and all three drowned in the flood. The torrent of water started with a surge five to six feet high, followed by a wall as much as 50 feet high that swept boulders, trees, and buildings before it. Witnesses described the sound as a "terrific unexplainable roar and grinding of hissing and swishing water." The flood spread out in the Gros Ventre bottomlands, wiping out homesteads and the steel-truss Gros Ventre bridge. Wilson was flooded, and the approaches to the Wilson bridge washed out. Nine hours after demolishing Kelly the high water surged past Hoback Junction into the Snake River Canyon.

The Kelly flood was Jackson Hole's greatest natural disaster; six people died in the flood; nearly 40 families lost their homes; state and county officials estimated property damage to be around $500,000. The village never recovered from the catastrophe. Only the school, church, and rectory survived the flood. Ray C. and Anna Kent bought up land in Kelly and eventually subdivided their property. By 1943, there were 14 residential lots. Kelly has evolved into a residential community comprised of year-round and seasonal homes. [33]

Other communities in Jackson Hole remained nothing more than post offices and sometimes schools, created to serve ranchers and homesteaders in a given locality. On occasion, postmasters operated a store or boarding house out of their residences.

South Park enjoys the distinction of having the first school in Jackson Hole. Sylvester Wilson allowed a room of his homestead cabin to be used as a classroom, and pioneers built the first schoolhouse on Ervin Wilson's property in 1896. The South Park Post Office was established on November 17, 1899, at the Francis M. Estes ranch, only to be discontinued on September 14, 1901. The Cheney Post Office replaced South Park on April 2, 1902, at the Selar Cheney Ranch. The Postal Service closed Cheney in 1917. [34]

Elk was one of the earliest post offices in the valley created to serve homesteaders in the Buffalo Fork-Spread Creek area. In the early years, the post office moved from ranch to ranch, with each change in postmasters causing confusion over its location. It first opened at the Pierce Cunningham ranch; Maggie Cunningham was the first postmaster. After Maggie Cunningham gave up the post office in 1899, the Wolffs took it over for 13 years. Ada Seaton was postmaster for less than a year, followed by Lizzie Allen. The post office was located at the Elk Ranch from 1913 to 1916. The postmasters shifted regularly over the next 16 years: Gertrude Steingraher, 1916-1918; Grace L. Brown, 1918-1922; Joe Chapline, 1922-1927; Charlton Chapline, 1927-1928; Juanita Hogan, 1928-1930 at the Hogan Fox Farm (the existing Buffalo Dorm); Viola Budge, 1928-1930; and Carrie Eldridge, 1930-1932. On October 5, 1932, Eva Topping took over the post office. For more than 30 years; the Elk Post Office was situated at the Moosehead Ranch, until it closed in 1968. Joe Chapline operated or leased the Elk Store, a small general store during the 1920s. [35]

|

| The Grovont Post Office was located at different farms along Mormon Row over the period of its existence. At the time of this photograph, it was located in the Chambers home. Jackson Hole Historical Society and Museum |

Another early community was Grovont, which served homesteaders in the flats east of Blacktail Butte. Grovont, a corruption of the French word Gros Ventre, was misspelled deliberately because the Postal Service liked post office names to be one word and easy to spell. Thus, they spelled Grovont as it was pronounced in French. Pioneer James Budge opened the post office at his homestead in 1899. His neighbor and close friend, James I. May, became postmaster in 1901. For the next 40 years, the Grovont Post Office shifted from settler to settler in the Mormon Row area, as it has been referred to since the 1920s. Mary A. Budge served the longest, from 1903-1908 and 1934-1941, when the post office closed. When the Mays managed the post office, they served meals and rented rooms to travelers. As more homesteaders, many of them Mormons, preempted land east of Blacktail Butte, the need arose for a church and school. In the summer of 1917, local residents constructed a frame Latter Day Saints meeting house on one acre of land sold by Thomas and Bertha Perry. School was held in the basement of the church that year. By 1922, a separate school had been built on acreage south of the Grovont Church. Both the school and the church were removed in the 1970s. The church was moved to the Teton Village road north of Wilson, where it houses a pizza parlor today. [36]

Teton was a small post office created in 1906 to serve settlers on the west side of the Snake River north of Wilson. It was situated first on the Kaufman homestead, then the Lower Bar BC, and finally the JY from 1914, until it closed in 1925. During the 1920s, local residents supported a local school. [37]

On the east side of the Snake River was the community of Zenith. Designated a post office in 1902 on the Harry Smith ranch, it served homesteaders north of the Gros Ventre River and east of the Snake River. Mail carriers made deliveries two to three times a week. In the Wyoming State Archives, there is a black-and-white photograph of a group of children and a young woman. The label identifies them as the class at "Zenith School, 1902." By 1900, Zenith was one of several school districts in the valley; in the 1920s, the school was located on the Waterman Ranch.

Other post offices existed, most of them forgotten today. Antler lasted less than one year from March to December 1899. Located either at the site of old Moran or Whiteman's Lakeview Ranch, Cora Heigho served as postmaster of this obscure post office. The Brooks Post Office, 1905-1912, provided mail service to ranchers far up the Gros Ventre. Slide, 1916-1920, was located at Lower Slide Lake. Later post offices were associated more with tourism than ranching. The Hoback Post Office, described as a "resort," received and sent out mail once a week. It opened in 1921 and provided service until 1943. [38] The Postal Service established the Moose Post Office in April 1923 at William Grant's store, situated in the Huckleberry Springs area along the Moose Wilson Road. The post office was moved to the local school near Menor's Ferry in 1929. At that time, Menor's Ferry became known as Moose. [39] The Moose area served a few homesteaders, dude ranchers such as the Estes, and others who catered to tourists, such as Maud Noble and the Dornans. At the end of 1923, Al Young relocated a sawmill in a marshy area near Moose, known as Sawmill Ponds today where he produced lumber for developments in the area. In 1925, Moose area residents held a meeting to establish a school. Buster Estes served as treasurer for a fundraising drive. They built a small log school in the sagebrush flats west of the ferry in 1925. In the same year, the Episcopal Church constructed the Chapel of the Transfiguration just west of the Menor cabin. Church dignitaries dedicated the chapel on July 26. After the Snake River Land Company bought Maud Noble's property, they leased the store for use as the post office and for commercial purposes. [40]

The Jenny Lake Post Office was established specifically to serve tourists. It opened in 1926 and operated during the summers only when visitors were present and facilities open. Housed first in a building owned by Homer Richards, it was moved to the Jenny Lake Store on the J. D. Kimmel property. [41]

Economically agriculture and tourism formed the economic pillars of Jackson Hole and shaped the character of its communities. The valley never experienced large-scale consumptive industries like logging and mining. Commercial timber cutting in Jackson Hole remained a small-time activity, dominated by local mill operators who produced lumber for local use. Successful mining would have created entirely different communities as well as severe impacts on the environment.

Prospectors and geologists have explored Jackson Hole for minerals since the DeLacy expedition of 1863, but always with marginal results at best. The mysterious Mining Ditch, dug in the 1870s, demonstrates serious efforts to extract gold from the Snake River. [42] Prospectors sought gold in the valley well into the 1920s, but found only enough color to cause frustration. A few ventured up the rugged canyons seeking gold or possible paying veins of silver and lead, again with no success. Gold brought Albert Nelson and Billy Bierer to Jackson Hole in 1895, but they soon turned to homesteading. In 1894, Denver's Rocky Mountain News reported that a group of miners from Cripple Creek, Colorado, ventured into Jackson Hole to prospect for gold. Their leader, W. T Sawyer, planned to return with approximately 100 people the next year. Sawyer filed a location notice for placer claims about one-half mile west of the present outlet of Jackson Lake in 1896. [43]

A few settlers panned for gold in the Snake and its tributaries for a living. They included such characters as Uncle Jack Davis and Johnny Counts, along with obscure prospectors such as Munger and John Condit. None of them became rich; Johnny Counts would wash 100 wheelbarrows of dirt per day gleaning about a penny's worth of gold per load. Friends of Uncle Jack Davis found a mere $12 and about an equal value of amalgam in his cabin after his death. Placer mining proved a hard way to earn a living. Samuel and Noble Gregory "rocked" enough flour gold to pay for winter supplies at their respective ranches, but did not try to make a living at it. Holiday Menor had prospected and worked the mines in Montana, but gave up the life in Jackson Hole. [44]

Nevertheless, the gold bug bit speculators periodically. The Teton County records indicate three distinct periods of activity, when both settlers and outsiders filed placer claims along the upper Snake River and its tributaries; 1895-1896, 1902-1905, and 1931-1934. Few secured their claims by proving them up in accordance with the law, and those who claimed to do so may have lied because no one had to verify their testimony. Finally there is no evidence that any of the claims were profitable. A prospector named Red Soper, working Deadman's Bar in 1916, reported good fishing at his claim rather than profitable mining. [45]

Prospectors continued to scout the country. In the first issue of the Courier, the editor wrote "Jackson has great possibilities as a mineral producer" according to miners familiar with the area. Copper bearing ore of 25 percent purity had been found in the Buffalo Fork area, prompting a Chicago company to raise $10,000 to finance a mine. Available evidence indicates that no mine was ever developed. E. C. "Doc" Steele directed the development of numerous placer claims owned by the Jackson Hole Mining Company, a local corporation. Doc Steele gave up the mining operation by 1911. He opened Jackson's first drugstore, then operated a saloon at Moran around 1913. In the Tetons, "high grade galena" had been discovered in the Fox Creek area at the head of Death Canyon and gold and silver ore had been found in the "western" hills. The ruins of a prospector's cabin exist on the Death Canyon Shelf and prospect pits and caves are extant in both Death and Avalanche Canyons. Along the Snake River in the southern end of the valley the Hoffer brothers placer mined gold in paying quantities. [46]

Because of the lack of promising mineral strikes, corporate investments in mining were non-existent, with the possible exception of the Whetstone Mining Company. Captain Harris attempted to establish a large placer mine and mill on Whetstone Creek, a tributary of Pacific Creek. He built a giant sluice box consisting of four-inch planks bored full of pockets by a two-inch auger. As riverine soils washed down the boxes, the heavier gold should have filled the pockets but failed as pebbles, rather than gold, filled the holes. Harris filled his own pockets with stockholders' money and disappeared. Other companies purchased placer claims such as the Tertillata Gold Mining Company and Golden Bar Steam Dredging Company in 1895, but never developed their claims. As late as 1932, a Chicago company set up a gold camp two miles south of the Elk Post Office during the speculation of the 1930s. [47] Like many other western regions, Jackson Hole has its own lost mine. In 1924, the Courier published a report about a prospector named John Hayball, who located a lode mine that produced high-grade gold ore. He interested two Idaho Falls men in the project, but died before revealing the site of the mine. [48]

In the north end of Jackson Hole, John Graul took up a claim in Webb Canyon in 1914. He painstakingly cut a tunnel into a basalt formation, but what he sought remains a mystery today. W. C. Lawrence, who had an asbestos claim in Berry Canyon, believed Graul sought platinum. Graul built a cabin, a tool shed; and cut a tunnel 193 feet in length. He returned to work the mine each season after the snow melted, until he was killed in a mining accident in Colorado in 1927. [49]

Coal became the only commercially viable resource mined in Jackson Hole. In the highlands east of the valley an exposed coal field exists in the northern and eastern areas. Approximately 60 miles long, and by 9 to 18 miles wide, the field comprises more than 600 square miles of coal-bearing rocks. Because the coal is exposed in many areas, pioneers knew of its existence and attempted to establish mines. In September 1891, a group of settlers gathered to form the Inta Coal and Mining Company to raise capital and develop coal mines in the Gros Ventre valley. Aside from changing the name of the company to the Jackson Hole Coal Mining Company; there is no evidence that the locally inspired firm succeeded. The Reclamation Service developed the first mines in 1914 to provide a fuel source for the Jackson Lake Dam. The mines were located on Lava Creek, a tributary of the Buffalo Fork, and on Pilgrim Creek. In 1917, the service opened the Lava Creek mine to the public.

In 1920, developers reopened the Jake Jackson Coal Mine on Cache Creek. Located closer to Jackson, this coal sold for $12 per ton, less than half the cost of coal from the Lava Creek mine. As local demand for coal for heating and cooking increased during the 1920s and 1930s, other mines were developed. Dick Turpin had dug a tunnel in the Gros Ventre deposit in 1892; but no coal was mined and shipped out until a better road was built in 1924. Entrepreneurs such as John Nocker, Jess Luton, and Claude Shearer developed mines elsewhere such as Granite Creek and Slate Creek in the Hoback drainage, Ditch Creek, and Coal Mine Draw near Spread Creek. Because the cost of exporting coal was prohibitive, the Jackson Hole coal mines served a local market and, as a result, remained small operations. Nocker mined coal into the 1940s. All of the mines are abandoned today. [50]

Oil exploration came to the valley in the 1920s. On April 11, 1929, the Courier reported that two companies, Utah Oil and Midwest Oil, intended to drill two wells in the area during the summer. No subsequent reports indicate that the wells were sunk. Companies have drilled exploratory wells in the area since that time and, stimulated by the energy crisis of the late 1970s, oil exploration has been a significant and sometimes controversial activity in the region. [51]

Overall, the communities in Jackson Hole evolved over time. With the possible exception of Moran, there were no boomtowns similar to those that characterized the miners' frontier. Agriculture, particularly cattle ranching, formed the economic base. Most of the communities consisted of a post office, supplemented perhaps by a school and, less often, a church and store. Nevertheless, residents developed a surprising loyalty to their locality. The country school not only educated the children, but served as a social center for meetings; dances, and important life events such as weddings and funerals.

Of all the communities in Jackson Hole, Jackson emerged as the dominant town. Its location in the southern part of Jackson Hole amidst concentrations of settlers gave the village a significant advantage over other towns. The first post office, the first general store, and the first community building also gave Jackson a significant head start. Later entrepreneurs located the first newspaper and bank in Jackson. Politically, the town moved ahead of its rivals, incorporating in 1914 and becoming the seat of Teton County in 1921. Wilson never competed seriously with Jackson as a commercial center. Kelly developed in conjunction with the homestead boom north of the Gros Ventre River after 1913, but was wiped out in the flood of 1927. Today Kelly is a residential community of year-round and seasonal homes. Moran was the first community to rely primarily on tourism, especially hunters and fishermen; rather than agriculture. Although Ben Sheffield's Moran no longer exists, it set an early course for the valley as tourism surpassed ranching as the primary economic activity.

Notes

1. Robert V. Hine, The American West; an Interpretive History, (Boston: Little, Brown, 1973), pp. 252-267; and Billington, Westward Expansion, pp. 534-535 and 619-629.

2. Hine, American West, pp. 252-253; and Marcus Whiffen, American Architecture Since 1780: A Guide to Styles (Cambridge, MA: The M.I.T Press, 1969), p. 87.

3. Hine, American West, p. 239.

4. Allen, Early Jackson Hole, p. 1.

5. K..C. Allan Collection, 7636, "Post Offices of Jackson Hole," University of Wyoming Archives, American Heritage Center; Mae Tuttle to Cora Barber, September 5, 1951, Jackson Hole Historical Society and Museum; reprinted in Jackson Hole Guide, December 5, 1974; and Wyoming Tribune, February 8, 1896 in Elizabeth Wied Hayden Collection, Subject File #5, Jackson Hole Historical Society and Museum.

6. Allan Collection, "Post Office, University of Wyoming Archives;" Jackson Hole Guide, December 2, 1965; Brown, Souvenir History; Hayden Collection, Subject File 5, Jackson Hole Historical Society and Museum; Hayden, From Trapper to Tourist, p. 50; and Jackson Hole Guide, December 14, 1972.

7. Brown, Souvenir History, p. 36; Jackson Hole Guide, October 14, 1965, and April 7, 1960; and Hayden Collection, Subject File 5, Jackson Hole Historical Society and Museum.

8. William Trester, "The Town of Jackson, June 1, 1907," photograph, Jackson Hole Historical Society and Museum. This is the earliest known photograph of the village of Jackson.

9. Hayden, Trapper to Tourist, p. 51; Jackson's Hole Courier, November 12, 1938; Jackson Hole News, November 1, 1978; and Jackson Hole Guide, October 9, 1952. Doctor Palmer's facility is sometimes referred to as an "insanitorium," although I could find no such word in dictionaries.

10. Jackson's Hole Courier, January 28, 1909, reprinted in Jackson's Hole Courier, January 29, 1948.

11. Ibid.; and Jackson's Hole Courier, April 30, 1914.

12. Brown, Souvenir History, pp. 11 and 36-37; and Jackson's Hole Courier, August 20, 1914.

13. Mumey, Teton Mountains, p. 307; and Jackson's Hole Courier, May 7, 1914.

14. Struthers Burt, Diary, p. 107.

15. Kemmerer Camera, April 18, 1918.

16. Jackson's Hole Courier, January 20, 1921, February 3, 1921, September 4, 1916 and March 23, 1944; and Brown, Souvenir History, p. 11.

17. Jackson's Hole Courier, January 6, 1921, June 16, 1921, April 11, 1918, May 2, 1918, June 6, 1918, and June 13, 1918.

18. Hayden Collection, Subject File 5, Jackson Hole Historical Society and Museum; Jackson's Hole Courier, August 18, 1948; interview with Martha Davis Riniker, transcript, File R, Jackson Hole Historical Society and Museum; and Jackson Hole Guide, September 23, 1965, reprint of Alice Winegar Diary.

19. Interview with Gretchen Huff Francis by Jo Ann Byrd, #16, "Last of Old West Series."

20. Jackson's Hole Courier, October 14, 1915, June 1, 1916, and May 16, 1915.

21. Saylor, Jackson Hole, pp. 143-146; and Jackson's Hole Courier, April 29, 1920, May 12, 1920, May 12, 1921, and May 26, 1921.

22. Jackson's Hole Courier, October 14, 1920, April 17, 1924, May 21, 1931, September 28, 1933, and July 17, 1941; and Jackson Hole Guide, January 25, 1973.

23. Jackson's Hole Courier, May 7, 1931, and April 28, 1932; and Jackson Hole Guide, December 29, 1966.

24. Jackson's Hole Courier, February 24, 1921.

25. Hayden, Trapper to Tourist, pp. 38-39; Brown, Souvenir History, pp. 33 and 35; Jackson Hole News, June 9, 1976; Allan Collection, "Post Offices," University of Wyoming; Jackson's Hole Courier, January 28, 1909; and interview with Walt Callahan by Jo Ann Byrd, #6, "Last of Old West Series." In 1976, the owners of the Wilson Hotel burned the building, citing prohibitive costs to restore the structure.

26. Office of Teton County Clerk and Recorder, Deed Record Book 1, p. 179; Deed Record Book 3, p. 95, A.R. and Nellie M. Kimball to Margaret Sheffield, Warranty Deed, April 12, 1915; Deed Record Book 3, p. 96, A. R. Kimball to B. D. Sheffield, Warranty Deed, April 12, 1915; Mixed Records Book 3, p. 337, Ed J. Smith to Charles P. Bartlett, Lease, November 16, 1900; Frank and Jennie Lovell to B. D. Sheffield, Warranty Deed, November 12, 1903; Lenore Diem, "The Research Station's Place in History," University of Wyoming-NPS Research Center, Moran, WY, 1978, p. 5; Allen, Early Jackson Hole, p. 304; Jackson Hole Guide, March 2, 1972; and John Markham, "The Temporary Jackson Lake Dam."

27. "Dude Ranches Out West," [ca. 1927], Union Pacific Railroad, S.N. Leek Collection, 3138, University of Wyoming Archives, American Heritage Center; Jackson Hole Guide, March 2, 1972; and Teton County Records, Deed Record Book 4, 62, B. D. and Margaret Sheffield to the Snake River Land Company, Warranty Deed, July 9, 1929.

28. Rockefeller Archive Center, Harold P. Fabian Collection, 1V3A7, Photograph, Collection Number 1047; Homestead Patent 708783, Norman Smith, 1918, and Jackson's Hole Courier, April 23, 1914, and September 3, 1914.

29. Jackson's Hole Courier, May 21, 1914, September 3, 1914, January 7, 1915 and January 6, 1921; Allen Collection "Post Offices;" and interview with Pearl McClary by Jo Anne Byrd, #25, "Last of Old West Series."

30. Jackson's Hole Courier, March 22, 1917, November 18, 1917, July 10, 1919, and October 20, 1921.

31. E. N. Moody, "Some Recollections of the Formation and Early History of Teton County," transcript, November 9, 1968, File H, acc. #305, Jackson Hole Historical Society and Museum; and Jackson's Hole Courier, May 12, 1921, February 3, 1921, April 28, 1921, June 16, 1921, June 30, 1921, July 14, 1921, February 1, 1923, and November 15, 1923.

32. Jackson's Hole Courier, May 20, 1926; interview with Jim Budge by Jo Anne Byrd, #5, "Last of Old West Series;" and Jackson Hole Guide, December 9, 1976.

33. Hayden, Trapper to Tourist, pp. 57-58; "Gros Ventre Slide Geological Area," pamphlet, U.S. Forest Service, U.S. Dept. of Agriculture, 1969; Jackson's Hole Courier, June 23, 1925, May 19, 1927, and May 26, 1927; Jackson Hole Guide, July 14, 1955, July 21, 1955, July 28, 1955, and August 11, 1955; Jackson Hole News, August 7, 1975; and Jackson Hole Guide, December 9, 1976, and August 12, 1971.

34. Brown, Souvenir History, p. 33; and Allen Collection, "Post Offices."

35. Brown, Souvenir History, 39; Allen Collection, "Post Offices;" and Teton County Records, Misc. Records Book 1, p. 481, Joseph Chapline to D. D. Eldridge, lease, September 17, 1927.

36. Allen Collection, "Post Offices;" Huidekoper, Early Days, p. 53; Jackson's Hole Courier, August 9, 1917, November 18, 1917, October 12, 1922, and June 11, 1925; and Teton County Records, Deed Record Book 2, p. 28, Thomas W. and Bertha Perry to J. Wallace Moulton, Warranty Deed, December 12, 1919.

37. Allen Collection, "Post Offices;" Brown, Souvenir History, p. 39; Jackson's Hole Courier, June 11, 1925; and Huidekoper, Early Days, 82.

38. Allen Collection, "Post Offices;" and Brown, Souvenir History, p. 35.

39. Allen Collection, "Post Offices;" Jackson's Hole Courier, June 11, 1925, and December 26, 1922; and Jackson Hole Guide, June 2, 1973.

40. Jackson's Hole Courier, December 20, 1922, February 22, 1923, November 20, 1923, June 19, 1924, June 11, 1925, July 30, 1925, and August 25, 1932.

41. Allen Collection, "Post Offices."

42. Fritiof Fryxell, "The Story of Deadman's Bar," Campfire Tales of Jackson Hole, pp. 38-42.

43. Jackson Hole Guide, March 21, 1957; Rocky Mountain News, December 6, 1894; and Teton County Records, Mixed Records Book 1, p. 288, W. T Sawyer, Location Notice, 3356, November 30, 1896.

44. Fritiof Fryxell, "Prospector of Jackson Hole," Campfire Talks, 47-51; Jackson Hole Guide, December 14, 1972; interview with Nobel Gregory, Jr. by Jo Ann Byrd, #13, "Last of Old West Series;" and Wyoming State Archives, Museums and Historical Department, Census of the United States, 1900, Jackson Precinct.

45. Teton County Records, Mixed Records; and Jackson's Hole Courier, February 10, 1916.

46. Jackson's Hole Courier, January 28, 1909.

47. Hayden, Trapper to Tourist, p. 30; and Jackson's Hole Courier, May 1, 1919 and September 29, 1932.

48. Jackson's Hole Courier, September 26, 1924.

49. Margaret Kelsey, "John Graul's Mystery Mine," pamphlet file, Grand Teton National Park, Teton Magazine; and interview with W. C. "Slim" Lawrence by John Daugherty, July 3, 1980.

50. R. W. "Jackson Hole Coal Field," Geological Survey, University of Wyoming; Jackson's Hole Courier, November 26, 1914, November 8, 1917, January 8, 1920, December 4, 1924, August 13, 1931, and May 26, 1932; Brown, Souvenir History, p. 25; and letter from Virginia Huidekoper, April 10, 1994.

51. Jackson's Hole Courier, April 11, 1929, and December 21, 1929.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

grte/hrs/chap13.htm

Last Updated: 24-Jul-2004