|

Grand Teton

A Place Called Jackson Hole A Historic Resource Study of Grand Teton National Park |

|

CHAPTER 18:

Picturing Jackson Hole and Grand Teton National Park

By William H. Goetzmann

This essay is concerned with the various ways in which Jackson Hole and Grand Teton National Park have been pictured by cartographers, artists, photographers, film makers, and television. Add to this dreamers and the present author's point of view, especially since almost all the pictures and films and vistas do represent unique points of view—including those of a visitor today who is concerned with the historical setting (memories) as well as shifting media and representations of this staggeringly beautiful place that is nonetheless haunted by its past.

|

| The Tetons—Snake River by Ansel Adams, 1942. National Archives |

The Teton Mountains that tower over Jackson Hole are among the most familiar landmarks in the American West. They have been photographed perhaps more than any other mountains in that vast region. Ansel Adams's striking view of the Snake River winding towards the majestic snow-covered peaks, made in 1942 for the Interior Department, is an image of grandeur that stands as the climax vision of the Grand Teton National Park, if not the whole Rocky Mountain West.

Now, in the late twentieth century, more people have seen this iconic picture than marveled at William H. Jackson's nineteenth-century photograph of the Mount of the Holy Cross in western Colorado. To a religious Victorian age, Jackson's 1873 photograph of a remote mountain face on which a huge cross made of snow hung glistening in the sun was the ultimate symbol of America's holy mission in the West. Thomas Moran's highly romantic painting of the Mount of the Holy Cross seemed to make it almost an American cathedral that far overshadowed anything from Medieval Europe. America's Manifest Destiny was reified, confirmed, christened, and blessed by the Almighty.

Ansel Adams's mighty view of the Tetons, on the other hand, as an icon for the twentieth century, says something else. It may denote a tourist and sportsman's destination but it does not stand for a mission of conquest. It denotes the pristine grandeur of nature—the towering beauty of all outdoors untouched by human presence, though we know, of course, that some human, some photographer, has framed, conceived and captured the scene. It needs no beckoning cross, however. Indeed, Adams's view of the forests, the curling river, and the mountain peaks begs that they be left alone the way they were a million years ago. [1]

We know now that that has not been the case. Image makers from accomplished painters to snapshot photographers have come to Grand Teton National Park to capture not only its natural beauty, but also glimpses of its history, the dude ranch era, and its colorful life. Jackson Hole, the lively town of Jackson, once a gambling mecca for cowboys and movie stars, and even the Tetons themselves, have become a fantastic tourist destination—not yet as overrun as Yosemite, Yellowstone, and the Grand Canyon. Indeed, since the struggle to create and expand the National Park was finally consummated by Horace Albright of the Park Service, John D. Rockefeller II, Franklin Delano Roosevelt and Congress in 1943, a different course has been taken. [2] Snake River Valley farms and ranch houses have been torn down or, like Dr. Horace Carncross's and Struthers Burt's famous Bar BC dude ranch, have been left abandoned. Today the cabins where famous literati gathered to fish and hunt and commune with nature, and the dance hall complete with an illegal whiskey still and bar where they gathered to play, is now a ruin, slowly being invaded by a bend of the Snake River. It is still the subject of tourists with cameras who, in their minds, appreciate its authentic rusticity and glamorous past.

|

| The Mount of the Holy Cross by William Henry Jackson, 1873. US. Geological Survey, William Henry Jackson #1276 |

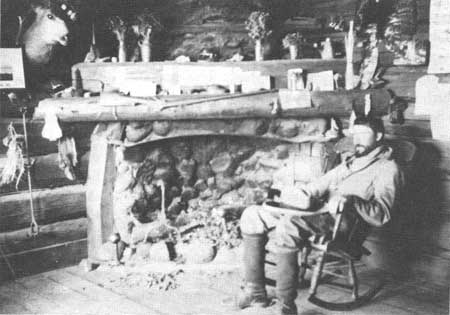

Mormon Row, part of which still stands out on a meadow in the shadow of Blacktail Butte, is testimony of the difficult Mormon trek over Teton Pass in 1893. It is dominated now by a barn, tin-roofed in fairly recent times, while the rest of the row, including a few houses, is slowly falling to pieces. Moulton Barn, on the other hand, also part of the Mormon settlement, still stands intact in all of its rustic glory with the Tetons rising behind it. There are also outbuildings and a sagging corral. The Mormons, like earlier settlers, ranched and had large hayfields spread out along Ditch Creek. Not far from it, to the west, near present day Moose, Wyoming, is the site of Menor's Ferry over which some of the Mormons crossed the Snake River. Nothing now marks John Holland's and John Carnes' Flat Creek Ranch, the first homesteaders in the valley in 1884. [3] It is now part of the Elk Refuge. We can visit the Cunningham cabin on Spread Creek where a posse from Jackson gunned down George Spenser and young Mike Burnett, thinking them to be cattle rustlers. But, John D. Sargents ten-room log lodge, Merymere, on the shores of Jackson Lake is gone. A photograph of John Sargent sitting contentedly by his fireplace remains. But the mysterious lodge, where Sargent (a relative of John Singer Sargent) believing his wife to be having an affair, drowned her "lover" and probably killed his wife by breaking both her hips, is gone. Later, for pay, he married a second wife who liked to play the violin while naked in a tree on the main trail to Yellowstone. But legendary Merymere (a name that would be cherished in Britain) is no more. Perhaps the tree is still there, but Merymere is gone, along with Sargent who, sitting in his favorite rocker before the fireplace, blew his brains out with a rifle when his exhibitionist wife was taken away and his support disappeared. [4]

Much history has been neglected or removed from Jackson Hole in favor of a return to nature where the preservation of the great elk herd seems primary, and where the buffalo still roam while visitors still hope to see antelope on Antelope Flats and moose feeding near glacier-made ponds. As one looks down from Signal Mountain, the whole valley seems empty with only the forest and the river and vast green meadows over which the Tetons and the National Park Service stand guard.

Despite the fact that the valley of the Tetons was never a crossroad of the West—to the mountain men the Green River or even Pierre's Hole to the west of the Tetons seemed more inviting for their rendezvous and to many a tourist it was a stop on the road to Yellowstone Park—it has been pictured many times.

|

| John Dudley Sargent, sitting by the fireplace at his Merymere lodge. Jackson Hole Historical Society and Museum |

Start with the maps since they are a picture of a part of the earth. William Clark's great manuscript map of 1810 shows John Colter's 1807 route from Manuel Lisas fort on the Big Horn through what is now Jackson Hole to Pierre's Hole. [5] The Tetons are not on this map. However, in Clark's map of 1814 that accompanied Nicholas Biddle and Paul Allen's History of the Expedition Under the Command of Captains Lewis and Clark published in Philadelphia in 1814, Colter's route past Lake Biddle (Jackson Lake?) and into the Jackson Hole region is shown, together with three clearly delineated mountain peaks overlooking the lake to the West. According to one authority, a party from the Northwest Company came far south through Yellowstone and into Jackson Hole where a French engagé named the mountains Les Tetons. [6] If this happened, the news of the Tetons does not appear on Chevalier Lapie's map of 1821, widely published in Nouvelle Annales des Voyages in Paris, though he seems aware of Wilson Price Hunt's travels through the Wind River Valley and Union Pass, as well as Robert Stuart's return through Jackson Hole and South Pass. Indeed Lapie's map was published along with an abridgement of Wilson Price Hunt's westward route and Robert Stuart's "traveling memoranda" of his return eastward via Jackson Hole, the Wind River Mountains and what came to be known as "the South Pass"—the route of American migration to Oregon and California. Perhaps Lapie's omission was due to American Fur Company mogul, John Jacob Astor himself who, while insisting that the news of the expedition be first published in the prestigious Nouvelles Annales de Voyages, by no means wished to provide explicit directions to his competitors in the fur trade including the British Northwest Company.

One really had to wait until English cartographer Aaron Arrowsmith's Hudson's Bay Company published his map of "British North America" (1834) to see the Tetons on a widely distributed map. By then, though Jackson Hole was well known to fur trappers, including the Americans David Jackson and Jedediah Smith, Arrowsmith misplaces it on his map. The next public cartographic exposure appeared on Captain Benjamin Bonneville's map of 1837 where the Tetons are placed somewhat north of Jackson Hole. Captain Washington Hood of the Corps of Topographical Engineers located the Tetons on his official Map of the United States Territory of Oregon published in 1838 obviously aimed to establish American claims vis-a-vis Britain to the Northwest region.

Earlier in 1836 the mountain man Warren Ferris had drawn a map clearly showing the location of Jackson Lake and the Tetons. This map did not come to light for over 100 years, nor did a similar map drawn by Jim Bridger. Still another map that locates, however carelessly, Jackson Hole and the Tetons is the celebrated Fremont-Gibbs-Smith map of 1831. This was a version of Lt. John C. Fremont's 1845 map of his circumnavigation of the West, possessed by George Gibbs of Fort Vancouver on which Gibbs placed all the geographical data known by the great mountain man explorer Jedediah Smith with whom, in 1831, he spent many weeks. This map, which so excited cartographic historian Carl I. Wheat and mountain man historian Dale L. Morgan, surfaced as late as 1954, though the information must also have appeared as early as 1831 as told also to Samuel Parkman who was readying Smith's journals and maps for publication just before the legendary explorer was murdered by Comanches on the Cimarron River while on the way to Santa Fe.

For a long period of time, Jackson Hole and the mighty Tetons were neglected except by a few settlers, ranchers and elk's tooth poachers who lived in sod-roofed dugouts. Because Elks Clubs spread rapidly over the United States the front teeth of the noble beasts were in high demand for club members watch chains. Luckily by 1900 the Elks Clubs did not require that a man possess such a tooth to be a member and the dwindling elk herds were saved.

In 1859 Capt. William F. Raynolds, guided by the legendary mountain man Jim Bridger, and assisted by a party of scientific men including Ferdinand V. Hayden, set off from Ft. Pierre on the Missouri to explore the Upper Missouri and Upper Yellowstone country for a system of wagon roads reaching as far north as the Mullan Road at Fort Benton and as far south as Fort Laramie. Needless to say, he failed in this ambitious mission even while leading his snow-bound and starving men including Bridger over the Continental Divide. He did succeed, however, in exploring and scientifically mapping the Jackson Hole area while Hayden made the first geological report on the Tetons and surrounding regions. His cartographer, J. H. Snowden, made six original maps. Blocked by snow, Raynolds never reached the wonders of Yellowstone. Instead he had to listen to Bridget tell him over and over about the geysers and paint pots in what must have been an exquisite form of torture, especially since Raynolds knew full well that if he could reach and explore the Yellowstone geyser basins, he would become famous. But it was not to be. Sketches of the Teton Basin by the artists of the expedition, J. D. Hutton and Antoine Schonborn, are possibly among the sketches at Yale. In 1871 Schonborn was to see and sketch the Yellowstone with Ferdinand V. Hayden's expedition. Schonborn committed suicide in Omaha, Nebraska, after the 1871 expedition to Yellowstone. [7]

In 1870, Lt. Gustavus Doane, a cavalryman, escorted a party of Montana businessmen and politicians into Yellowstone that included N. P. Langford, Henry D. Washburn and Cornelius Hedges. They explored its wonders and determined to make it a national wilderness park. [8] They sent articles and sketches to Scribner's Magazine that were turned into surprisingly accurate illustrations by the artist Thomas Moran who had not yet seen Yellowstone and its marvels. Because the party entered from the north at Fort Ellis, Montana, Jackson Hole did not figure in their itinerary. Perhaps they did not even know of it.

The most important early map of the Jackson Hole area was made by Gustavus Bechler on Professor Ferdinand V. Hayden's second expedition into Yellowstone in 1872. [9] In 1871, Hayden, head of the United States Geological Survey of the Territories, sponsored by the Department of the Interior, had led an extensive exploring expedition into the Yellowstone region, taking with him the artist Thomas Moran and the photographer William H. Jackson. Moran's sketches and Jackson's photographs, together with the intense lobbying of N. P. Langford and the railroad tourist interests of Jay Cooke, convinced Congress to make Yellowstone the nation's first national wilderness park.

Hayden's expedition of 1872 was most relevant for Jackson Hole. The professor and his men, now famous, explored and mapped the Jackson Valley and the Tetons. James Stevenson, Hayden's primary assistant, led that wing of the expedition. Stevenson and N. P Langford climbed to the top of Grand Teton Peak. It was a claim that was first disputed by William O. Owen, who climbed the peak in 1898, and has been disputed ever since. In fact, due to Owen's relentless lobbying, in 1926 the legislature of Wyoming proclaimed him the first to ascend to the crest of the Grand Teton. [10] Most importantly however, Bechler's map represented the most extensive and careful delineation of the region made to date. It was a climax view, and Hayden's party named most of the features of the region, including Jenny Lake, a memorial to the heroic Indian wife of mountain man "Beaver Dick" Leigh, an early settler in the region. One of the Tetons was named Mount Moran after the spectacular artist who had accompanied the 1871 expedition to Yellowstone.

In the summer of 1873, Captain William A. Jones also explored in Jackson Hole and produced another carefully-drawn overall map together with 49 specific geological and geographic maps, plus a spectacularly colored overall geologic map by Theodore Comstock. [11] This was the first thorough scientific study and view of the geologic history of Jackson Hole, which is so complex and interesting, with the great fault bloc Teton Range thrust upwards over a lower plate, and then the massive eroded valley formed by ancient glaciers, leaving boulders, moraines and drumlins and the winding Snake River, ever-shifting, its former banks forming hillocks that trace its ancient course. Comstock's study and vivid map opened a whole new area of "picturing" Jackson Hole. It began to resurrect its ancient history.

There have, of course, been many subsequent cartographic images of what is now Grand Teton National Park, especially important maps that delineated the increasing extent of the park including John D. Rockefeller Jr.'s enormous contribution. During the struggle to enlarge the park from its 1929 founding to its 1943 final boundaries that created the adjoining Jackson Hole National Monument, maps were naturally crucial, especially to Rockefeller's Snake River Land Company that was secretly buying out the valley's ranch properties. [12]

Cartographically picturing the region will probably never really end. Standard United States Geological Survey (U.S.G.S.) topographical maps are today being replaced by detailed Landsat space satellite maps made under the auspices of the United States Geological Survey and the National Aeronautics and Space Agency. For most people, pictures mean paintings, drawings and photographs. So many of these have been made over the years, especially by tourists, that only the highlights can be considered here. It is likely that J. D. Hutton and perhaps Antoine Schonborn, the artists who accompanied Capt. William F. Raynolds's expedition into the valley in 1860, were the first artists to sketch Jackson Hole.

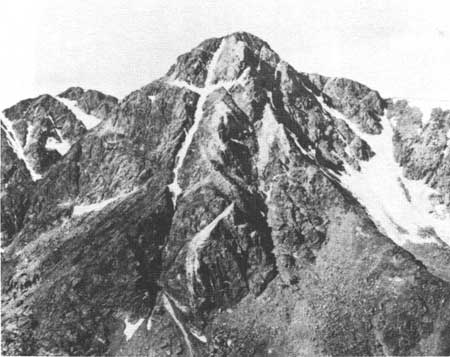

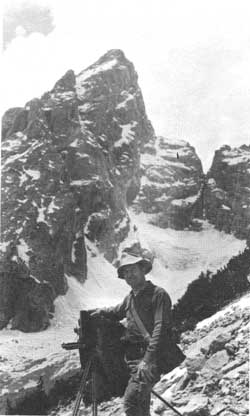

William H. Jackson, in 1872, was the first to photograph the Tetons. He did so from a base camp in Pierre's Hole on the west side of the mountains. For eight days Jackson and his assistants struggled with heavy cameras and stubborn mules to climb high enough to make an unobstructed and spectacular view of the central Tetons. He succeeded finally, but still from afar, with lesser peaks and valleys, including that of Glacier Creek intervening. On the ninth day Jackson finally found himself face to face with the west side of the Grand Teton peak, 13,747 feet high. He himself was variously out on a ledge on Table Mountain on the Idaho side and then in a cleft between two major outcroppings. Jackson was well aware of the adventure in photographing the Tetons. He had one of his assistants make a wet plate photograph of him with another assistant, his camera and his small portable darkroom tent way out on the edge of a high precipice with the three Tetons looming in the background miles away. Jackson, in the fashion of Eadweard Muybridge, was often into self-dramatization, but this photo is one of his classics. Later Jackson would enter Jackson Hole proper on the east side of the Tetons and make numerous photographs from what have become familiar tourist vantage points. [13] Some of these he would turn into post cards, later sold by the Detroit Publishing Company. One of his better views from east of the Tetons is a long-range flat panoramic view across the Snake River that captures virtually the whole mountain range in the picture. It prefigures Ansel Adams's stunning view but with far less drama. This photograph was probably made in 1878 when Jackson joined Hayden's last field survey that took him and a photographic division through Jackson Hole. The party, led by Hayden himself was accompanied by William H. Holmes, one of the great topographic artists of his time. The 1878 expedition entered via Hoback Canyon to the south. From Hoback Canyon, Jackson proceeded northward through Jackson Hole, following the Snake River into Yellowstone. Jackson wrote very little about Jackson Hole and the Tetons in his autobiography so he must not have been as impressed by its beauty as he was by the fireworks at Yellowstone. Perhaps, after seven years of photographing landscapes, he was jaded. Many of Jackson's photographs can be found in the picture archives of the U.S.G.S. in Denver. Jackson was fortunate that his Yellowstone and Jackson Hole photos and camera survived. As early as 1871, Capt. J. W. Barlow, leading a military expedition into Yellowstone, took along Thomas J. Hines as a photographer. Hines's photographs arrived in Chicago just in time to be destroyed in the great fire of that year. [14]

|

| Panoramic View of the Great Teton Range, Looking East by William Henry Jackson, 1872. Note figure standing on the peak in the middle-right foreground U.S. Geological Survey, William Henry Jackson #410 |

Another of the West's great photographers was F. Jay Haynes of Fargo, North Dakota. Haynes, along with Jackson, was perhaps the most enterprising of all western photographers. He worked under contract with the Northern Pacific Railroad for many years, photographing the building of the road as well as the scenery and towns along its transcontinental route. As a major part of his equipment he had his own railroad car studio—"Haynes Palace Studio." He first entered Yellowstone in 1881, only three years after Hayden had mapped it and Jackson had made his final photos of the scenery. Immediately Haynes saw the tourist possibilities of Yellowstone and applied to the Secretary of the Interior for an exclusive photographer's concession in the park. With annual persistence he got his exclusive concession in 1884 and land upon which to build two substantial studio buildings—one at Old Faithful and one at Mammoth Hot Springs.

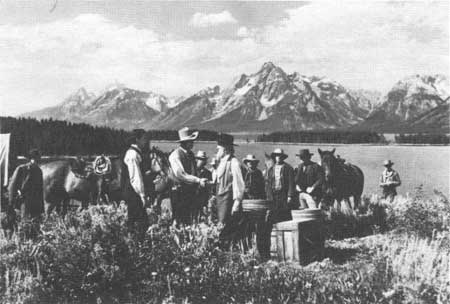

But even as he was applying for the concession at Yellowstone, Haynes explored Jackson Hole for other photographic possibilities. In fact, he became the official photographer for President Chester A. Arthur's excursion to Yellowstone and Jackson Hole in 1883. Haynes took a memorable group photograph of President Arthur flanked by General Philip Sheridan and Secretary of War Robert Lincoln. The red-faced, mutton-chopped Arthur is seated, wearing a tam like some feudal Scottish chieftain. The excursion permitted no reporters or women, and at each of his three camps in Jackson Hole—Gros Ventre River Canyon, on the Gros Ventre near Blacktail Butte, and along a bend of the Snake River just below the fork of the Buffalo River—a bar tent was prominent. When the explorers weren't fishing, Arthur's favorite sport, they were drinking in a sort of Bohemian Grove, male-bonding camp in Jackson Hole. On one occasion, when the Indian guides staged a war dance for the President, one of the drunken dancers nearly "whacked Great Chester on the head!" Haynes, of course, photographed the dance that must have been a high point on what one author has called "The Bottle Trail." [15]

Indeed, Haynes took a number of splendid photographs on the trip. The Tetons, of course, dominated many of his pictures that also often feature Indian scouts astride horses on a strong foreground of meadow, gravel or sand bars. One photo is certainly a harbinger of modernism. It featured bands of light and dark horizontally across the picture, making the Teton Valley scene almost abstract. The foreground is a light gravel bar, then the dark Gros Ventre River, then another thinner streak of light gravel, then a bank of dark trees and, finally, a distant view of the Tetons as the focal point of the picture. New York's avant garde Photo-Secessionists would have liked it, even though it was a bit in advance of their own art photographs.

Several other of Haynes's pictures remind one of Edward Curtis's early Alaska work (1899). [16] One camp scene features the pith-helmeted president looking out across the Snake River from his camp in the evening—a sunset glow just beyond the distant Tetons. Another is a tight shot of an Indian guide framed by two trees with the Tetons merely a back drop in the distance. Still another sequence of photos appear to be self-portraits and experimental shots. The first shows a black cowboy hunter holding a mule in a broad field before the overwhelming presence of the Tetons. Haynes is sprawled on the ground. Then in a stereoscope repetition of the scene, the mule has vanished. Clearly, in many of his surviving photographs, Haynes was not only trying for artistry, but also challenging the overwhelming presence of the Tetons by using interesting dark and light foregrounds that often included, but did not necessarily need, human figures even for scale. The enterprising Haynes is often thought of as a huckster, a mere post card photographer, but his scenes of Jackson Hole and the valley testify to his conscious attempts at artistry.

|

| President Chester A. Arthur, seated center, toured Yellowstone and Jackson Hole in 1883. F. Jay Haynes was the official photographer for the presidential excursion. |

In 1888, five years after President Chester A. Arthur "explored" Jackson Hole while F. J. Haynes took the picture, a number of trappers entered the valley. One of these was Stephen Nelson Leek, who hailed most recently from Nebraska. In the winter of 1888 he lived in a cabin built by Beaver Dick Leigh. Soon he staked out his own homestead three miles south of present day Jackson. He was one of only forty settlers who braved the winters of the valley. Soon Leek was taking hunting parties and dudes through the mountains. One of his "dudes" was George Eastman who gave Leek a Kodak view camera. While running a sawmill, a dairy farm, later a cattle ranch, dude ranch/hunting lodge and writing many poems and articles, Leek became one of the foremost photographers in the country. He photographed the scenery, of course, but he was best known for his wildlife photographs. Elk were his specialty. He knew their habits so well he could camouflage himself in a small snow fort, load and train his camera and then whistle the elk to attention while he snapped his shutter. Leek proudly asserted, "It is not often you get so close to wild elk as to be able to ask them to hold their heads up and look pleasant." [17]

Soon Leek was seeing his wildlife and scenery photographs published in most of the outdoor magazines and even The United Geographic Magazine. He had also sent off to France for a new Pathe movie camera and projector. With his motion pictures and slides of the plight of the elk in Jackson Hole, Leek went on to the Orpheum lecture circuit and even spoke before Congress. The estimated 12,000 elk in the valley were starving in the winter as the cattle ranchers built fences around their haystacks. Leek described them as "living skeletons of once noble specimens." [18] In the winter of 1908-1909 people could remember walking miles on the strewn bodies of dead elk. And then there were the elks tooth robbers who sold many a tooth from these dead, starved animals to the Elks Club where they were made into fashionable watch fobs.

|

| Ranchers fed all the hay that could be spared, but the desperate animals still raided fenced haystacks. The feed within reach was not enough to save them. Stephen Leek, Jackson Hole Historical Society |

Thanks to Leek's photography and cinematography, as well as his tireless crusading, the Wyoming Legislation in 1909 appropriated $5,000.00 for grain to feed them. The next two years Congress bought 3,500 acres along Flat Creek to create a national Elk refuge that gradually rose to its present size of 23,000 acres. Clearly Leek was the most effective photographer of Jackson Hole and one of the unsung heroes of the American Conservation Movement. [19] As a poet he was interesting as well:

"And when I hit that emblazed trail,

across the Great Divide,

Grant that my resting place may be

By Old Snake River's side." [20]

Perhaps the central figure in Jackson Hole photography was Harrison "Hank" Crandall. Originally from Newton, Kansas, Hank Crandall was first inspired to be a Teton Valley photographer by a William H. Jackson photo of the Tetons that he saw in a grade school geography book. [21] Crandall was a generation later than Jackson, but Jackson lived so long he became Crandall's contemporary and actually visited him at Jenny Lake in 1929 at the dedication of Grand Teton National Park. Crandall was also a generation younger than Haynes. He came to Jackson Hole, after service in World War I, in 1921. The following year, he brought his wife Hildegarde, some camping equipment, and a 3A Special Edition Eastman Kodak camera to Jackson Hole in a Ford Model T that bumped over roads that had "not yet been built." He made friends with the storekeeper at Moran, spent the winter as his renter, and the following spring staked out a homestead claim east of String Lake, near what is now Jenny Lake Lodge. Crandall built a log cabin and began his career as a photographer and landscape artist. When Grand Teton National Park was established in 1929, Hank sold his cabin and moved the substantial studio and showroom that he had built to the Jenny Lake area, where it still stands. He was a family man, however, and with the birth of two daughters he was persuaded to move to Boise, Idaho, for their education. Jackson Hole had only primitive schooling. He came back to Jackson Hole every spring and summer to continue his painting and photographic business which, like Haynes's at Yellowstone, was made a park concession at the behest of Horace B. Albright, then Director of the National Park Service. Crandall made scenic photos of the Tetons that he sold as park mementos or as post cards. He did a good business during the dude ranch era of the twenties and thirties, during which time writers like Owen Wister, who wrote The Virginian (ca. 1902), stayed at the Bar BC Ranch.

|

| Harrison Crandall is Grand Teton National Park's best known photographer. His former studio now serves as the visitor center at Jenny Lake. National Park Service |

As early as 1921, Crandall was selling pictures to dudes as fast as he could make them. All through the twenties he sold countless photos of dudes in cowboy outfits—or cowgirl outfits. Celebrities like Cissy Patterson Gizycka, heiress to the Chicago Tribune fortune, a Polish countess on the loose and the wildest woman in Jackson Hole, had her picture taken by Crandall while at the Bar BC Dude Ranch, although her paramour, Cal Carrington, the foreman at the ranch, allegedly a former horsethief probably avoided Crandall's lens. [22]

Crandall's photos were exuberant and theatrical, far from the brooding darkness of his contemporary, Ansel Adams. One of his best photos is a self-portrait showing him far up among the snowy crags of the Tetons. Another, in color, showed a mountain climber dangling from a rope below a mountain ledge. He liked to see the Tetons and his subjects stand out against blue skies. He also produced documentary photos for motion picture company location scouts, frequently using his panoramic camera that produced 7 x 17-inch negatives. But, because ranching, cowboys and dudes were at every hand, he photographed them more often than the Tetons. At the same time, he painted delicate pictures of the valley's wildflowers and made them into collector's item post cards. And when he had time he did paint his beloved Tetons. His work went all the way to the East Coast, appearing in magazines and calendars and in John D. Rockefeller's dressing room. In 1931, Rockefeller wrote Crandall, "The beautiful colored picture you gave us when we were here last has been framed and hangs in my dressing room. It gives us constant delight." The affable Hank Crandall, who liked to photograph pretty cowgirls and handsome cowboys, was a romantic in the Roaring Twenties way out West. [23]

Ansel Adams, born in 1902 in San Francisco, provided a contrast with virtually everyone else who photographed in Jackson Hole. Very much the art photographer from the beginning, he came to know Alfred Stieglitz, Paul Strand, Edward Weston, Imogen Cunningham, Mabel Dodge Luhan, Georgia O'Keeffe, and Beaumont and Nancy Newhall of the Museum of Modern Art. In 1920, dazzled by Yosemite, he decided to become a professional photographer and a pillar of the Sierra Club. He even married Virginia Best in Yosemite in 1928. [24] Photographing Yosemite had a long tradition from C. L. Wead's first efforts to those of Carleton Watkins and Eadweard Muybridge. Adams was certainly challenged by their work as he began his career photographing Yosemite and the high Sierras. He also admired the matter-of-fact work of the early survey photographer, Timothy O'Sullivan, who was deliberately not an art photographer.

Ansel Adams became an institution as a photographer. He had over 500 exhibitions, his own gallery in San Francisco, and a studio in Yosemite. He traveled all over the West, making his extraordinary photographs. He even developed the "Zone Method" of controlling light and dark in his black-and-white pictures. [25] This was followed by several other books and films on photographic techniques as Adams seemed to "scientize" photography while developing techniques that almost mechanically lent high drama to his pictures.

This chapter started with a description of Adams's striking but dark picture of the Snake River and the Tetons in a rainstorm—a picture that became an American icon. He made many other photos in Jackson Hole, probably in 1942 when Secretary of the Interior Harold Ickes commissioned him to photograph all the national parks. A look at a series of Adams's pictures reveals not a man with dudes or tourists in mind, but a person with an inner feeling and a tremendous ambition to control his scenes like Renaissance artists. He photographed a spare, slanted view of the Tetons and Jackson Lake at sunrise. It could be a Japanese print. He did Mount Moran with bands of light-colored aspens and dark pines dominating one half of the picture. Mount Moran is seen almost as a three-dimensional backdrop, indicating that Adams was respectful of the mountain but not dominated by it. There were other pictures of Mount Moran, some in which the storm-clouded sky dominated three-fourths of the picture, making the Tetons recede to a far less commanding position. Like all the other photographers who had visited the valley, he was challenged by the Tetons. In one photo, Tetons and Jackson Lake, Driftwood, the driftwood seems like a mountain from which he views the Tetons and their reflection far across a lake. Edward Curtis had used this technique on his trip with E. H. Harriman to Alaska in 1899. [26] Many of Adams's pictures feature water or stands of trees rather than the mountain. He is in control of nature just as is his organization, the Sierra Club. In one of his best pictures, Adams really ignores his subject, Mormon Row, and entitles his picture incorrectly Ranch and Mount Leidy, Jackson Hole. He is facing east, away from the Tetons. Adams is now passing out of fashion in the march of the "New Topographers" like Lewis Baltz, Robert Adams and Len Jenshel who photographed the West as a deteriorating suburban wasteland—in Peter Blake's term "God's own junkyard"—or Peter Goin, Richard Misrach and Patrick Nagatani, who delight in photographing atomic testing sites in Utah and Nevada. They see the west as Death Valley, a total Zabriski Point. Or, like Mark Klett in his re-photographic project, they trace the changes man and time have wrought on, say, O'Sullivan's familiar photo landmarks of the nineteenth century. [27] None of these new topographers have worked in Jackson Hole, probably because, as much as possible, with the exception of Jackson itself Teton Village and the Rockefeller Lodge, traces of human activity have been extensively effaced, though some farms and ranches remain, dotting the valley. Man is not prominent in nature.

|

| Below Zero-Bison by Thomas Mangelsen. Mangelsen, a wildlife photographer who has traveled throughout the world, has done some of his finest work in Jackson Hole. Thomas D. Mangelsen |

Three modern photographers have also done striking work in the Tetons. One, currently operating out of Omaha and Jackson, Thomas D. Mangelsen, is a wildlife photographer. Though he has traveled to Arctic regions and Africa making color photos of animals and their exotic locales, some of his best works have been of wildlife in Jackson Hole. One that stands out profoundly is a picture of two lonely buffalo on a windswept rocky plain with the temperature far below zero. Seen through a filter in a chilling blue atmosphere, they stand outlined against the snow-covered Tetons almost obscured by clouds of blowing snow off of which the dim winter sun is reflecting. Mangelsen has done other chromatic photos of the Tetons themselves but his trademark is a sensitivity to animal life, and where they fit in their particular ecosystem. Many of these appear in his book Images of Nature: The Photographs of Thomas D. Mangelsen. [28]

Perhaps the premier color photographer of the national parks is David Muench. His photographs of Grand Teton National Park are spectacular. They appear in his book, National Parks of America, together with a text by a former Secretary of the Interior, Stewart Udall and his brother, James Udall. By the late twentieth century, when environmental issues are at the political center stage, it is almost mandatory for Interior Secretaries to commission art photographs of America's wilderness areas as a subtle form of political propaganda. Muench's photographs, however, are special—perhaps the best western photographs ever made. In his National Parks of America, Muench includes four stunning views of Grand Teton National Park. The most spectacular perhaps is January Dawn: Teton Range, rose red as taken through a filtered lens. Two pictures feature Lake Solitude, one with a misty "snowmelt design" that not only reflects the Tetons in the hidden lake but also appears to cast a halo around them. The fourth picture, Moonset, Grand Tetons, features a daylight moon over the pinkish Tetons which makes them look deliberately artificial. Muench's photographs have appeared in such magazines as National Geographic, New York Times, Wilderness, Outdoor Photographer, Photographic, Life, Sierra and the Smithsonian Magazine. Recently he has been working with his son Marc Muench whose landscape photographs follow in his father's footsteps but also sometimes include human figures. [29]

Still other photographers of note are Ed Riddell and Jim Olson whose stunning scenes in both black and white and color illustrate a reprint of the legendary geologist of Jackson Hole, Fritiof Fryxell's little classic, The Tetons: Interpretations of a Mountain Landscape. Olson's views are from the tops of the Tetons or close up among the peaks, thus offering relatively unusual points of view affording panoramas of the valley or the intimate high up views of the mountain climber, for the Tetons are very often the destination of such adventurers. Riddell's views are moody with storms and sunsets in the manner of Ansel Adams. [30]

Another contemporary photographer, Frederic C. Joy, immigrated to Jackson Hole from Utah in 1958 to continue the family tradition of scenic photography started by his grandfather, who was married to the gorgeous Miss Utah of his day and termed by a disgruntled Struthers Burt, a former partner, a "Bluebeard" in 1911. Frederic C. Joy, his grandson, does not have Miss Utah in tow, but he has made what are among the most refreshing color photographs of the Teton region. Much of his work is reminiscent of Eliot Porter's pictures of the Glen Canyon of the Colorado. [31] These are close-up abstractions of erosions of the Tetons by glacial melt-water unlike those of any other photographer in the area. Besides these abstractions, Joy celebrates the fields of flowers and golden aspens that lie before the Tetons, as well as historical landmarks like the Bar BC Ranch, its red-roofed saddle barn in the foreground before a background of autumn trees and the Tetons in the distance.

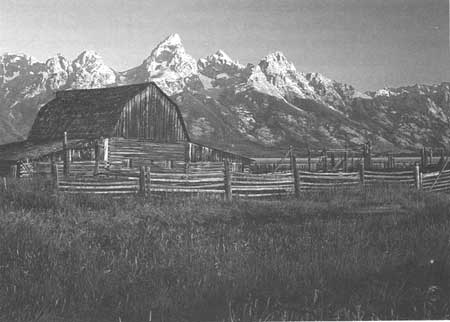

But what of the millions of people with Nikons and Kodaks who take pictures in the park—of the Tetons, the wildlife, themselves? Robert Bednar, a recent student of mine, has argued that all of these pictures, such as those of the Moulton Barn, the most photographed barn in the West, do not represent reality but the hyper-real. [32] They represent, according to Bednar, the photography of the already expected. In the poet Ezra Pound's terms they are "shades of a shade," "daguerreotypes of a likeness," [33] pictures of pictures already made a thousand times. As such, Bednar sees them as artificial simulations and, therefore, a dead end as to reality and contact with nature itself. Could this be true of Jackson Hole with its iconic Tetons? Is it all a cliche?

The historian Carl Becker once wrote an essay entitled "Everyman his own historian." I wonder if the millions of snapshots aren't really discoveries, re-exploration of a part of the earth thought to have been discovered, mapped and pictured by mountain men, explorers, surveyors and professional photographers? Hand-held camera visitors to the Teton Valley are likewise explorers. They may pit themselves consciously against, or in imitation of previous photographers, but with new equipment, new technology and different, even ironic, outlooks, they really are making the age-old landscape—new. It is a struggle to make something new—except babies.

The number of artists, professional and amateur, who have painted in Jackson Hole is incalculable. Some names are unfamiliar: Jenny Mabey, John Fery, Charles Chapman, a prolific artist and influential teacher, Ulysses Dow Tenney, Quita Pownall, Charles Partridge Adams, a prominent Denver artist who painted the Tetons on one occasion, but roughly 800 paintings of Colorado. Others like Gilbert Munger of the Federal Lithographic Bureau who made the chromolithographs for Clarence King's Systemic Geology (a key U.S. 40th Parallel Survey volume) are barely known even to scholars. A few, such as J. D. Hutton and Antoine Schonborn, who accompanied Capt. Raynolds in 1860, made some pencil sketches and watercolors that have survived at Yale. [34]

Harrison Crandall, who found some time in the 1920s to paint beautiful panoramic views of the Teton Valley, will ultimately be remembered for his careful color renditions of 32 different species of wildflowers to be found in the valley. His work in this respect was more than a hobby, it was of prime importance to the United States Biological Survey. These delicate paintings represent an ecological cross section of the valley, circa 1920-40. [35]

That grandiose painter of the scenic West, Albert Bierstadt, traveled west on a wagon road trip to the Wind River Mountains with Frederick West Lander in 1859-60. Then he made a visit to Yellowstone Park in 1881, part of a three-month journey through the West. As a result, at least six paintings of the Tetons and Jackson Hole are attributed to him. They have titles like Teton Range, Moose, Wyoming, when there wasn't a Moose, Wyoming, at the time, and Rainbow on Jenny Lake, Teton Range, Wyoming, a garish and sentimental work possibly derived from stereographs taken by his brother Charles, a Niagara Falls photographer who made stereo pictures throughout the West. Other views, entitled Grand Tetons, In the Tetons and Landscape with Waterfall, Study for Scenery in Grand Tetons seem inaccurate. Certainly none capture the stunning majesty of the Tetons, which, if he had actually seen them, might well have soared to five or ten miles high. According to the best authorities, Bierstadt invented his Tetons, Jenny Lake and its rainbow, and Moose, Wyoming. [36]

|

| The Three Tetons by Thomas Moran, 1895. Moran's painting of the Tetons from the Idaho side now hangs in the Oval Office of the White House, facing the president. The White House |

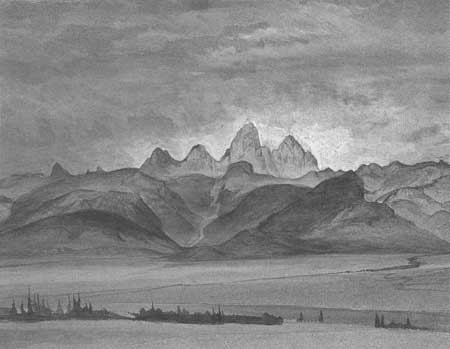

The other "grand" painter of the Tetons was Thomas Moran. Between August 21 and August 29, 1879, escorted by Capt. Augustus Bainbridge, some troopers of the 14th Infantry and some Indian scouts, he made an excursion from Fort Hall, Idaho, along Teton Creek west of the Tetons, hoping to cross over into the Snake River Valley. He never made it, despite being guided by local Indians. On August 23 he wrote in his diary while still west of the Snake River Range, "The Tetons are now plainly visible but not well defined owing to the mistiness of the atmosphere. They loom grandly above all the other mountains." [37] He was at least 22 miles away. By the 25th he could note in his diary, "The Tetons have loomed up grandly against the sky. From this point it is perhaps the finest pictorial range in the United States or even N. America." Later in the day he wrote, "This afternoon we made sketches of the Teton Range but the distance, 20 miles, is rather too far to distinguish the details, especially as it is very smoky from fires in the mountains on each side of the peaks." The next day he came upon Beaver Dick Leigh and his wife Jenny. They were trapping beaver. On the 27th it rained. They started their return on the 28th; on the 29th of August, Moran's notebook diary ends. The wonder is that Moran was able to produce at least four decent sketches of the Tetons. One sepia-colored watercolor is known to have been done on the 26th. It views the distant Tetons across a vast plain and over an intervening mountain range. Another watercolor, The Tetons is painted from a point very near the place where William H. Jackson had made his photograph on a ledge high up on Table Mountain. It is a dramatic, snow-covered storm scene rendered by Moran in blue and white. It is possible that this sketch was, in fact, influenced by Jackson's photograph. Later, possibly in 1890, when he was participating in the U.S. Indian census, Peter Moran, Thomas's brother, also painted a substantial multi-colored watercolor 12 x 18-inch view, Grand Tetons View, that now hangs in the Roswell Museum, Roswell, New Mexico. [38] More recently, a number of Moran pencil sketches have been on display at the Natural Wildlife Museum just outside of Jackson, Wyoming. They are from the collection of the Grand Teton National Park Visitor Center near Moose, Wyoming.

It is unfortunate that neither Bierstadt nor the Morans really got into Jackson Hole and thus we have no grand "Big Picture" by any of them of the face of the Grand Tetons. An 1895 oil painting by Moran of the Tetons, from the Idaho side, does hang in the Oval Office of the White House, facing the president. There are three other oil paintings of the Tetons by Moran: The Teton Range (1897), The Teton Range (1899), and the recently discovered Solitude (1899). The latter appears to have first been a depiction of the Rocky Mountains that Moran converted to a Teton picture by simply painting the three Tetons in white above the Rockies' horizon line. Solitude and the other Teton paintings were clearly based on the field sketches, though the foreground, a rushing river and part of Lake Solitude, resembles the foreground of his painting of the Mount of the Holy Cross. As Moran got older his western scenes became more standard and dependent on much earlier work. Both Bierstadt and Moran missed the chance of a lifetime, though Moran, on his return trip from Pierre's Hole west of the Tetons eventually made numerous sketches of the majestic cliffs of the Green River from which he made many salable paintings. Family lore has it that his daughter used to say, "whenever we needed money, papa painted another Green River."

|

| Grand Tetons View by Peter Moran. Peter Moran (who was Thomas Moran's brother) probably created this watercolor painting in 1890, when he participated in the U.S. Indian census. Permanent Collection, Roswell Museum and Art Center |

Because these two famous grand landscapists of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries never entered the Valley of the Tetons, they missed one of the great subjects for the landscape artist—one that with its many colored foliage and majestic peaks would have been almost perfect for their talents and romantic spirit. By contrast, perhaps in compensation, we do have one grand panoramic drawing of the Teton Valley by the West's foremost topographic artist, William H. Holmes, most famous for his breathtaking scientific renditions of the Grand Canyon to accompany Capt. Clarence Dutton's Tertiary History of the Grand Canyon District (1881). Holmes's wonderful panorama of Teton Valley appears in the portfolio Maps and Panoramas that accompanied F. V. Hayden's last Report of the United States Geological and Geographical Survey of the Territories (1878). [39] Holmes would later become the Director of the Bureau of American Ethnology, though he was also a significant artist and an expert on structural geology. His observations made John Wesley Powell's Report on the Geology of the Eastern Portion of the Unita Mountains (1876) a classic, and he painted a splendid view of a laccolith formation or giant dome that constitutes the basic formations of both Yellowstone and the Grand Canyon. Holmes's panoramas of the Tetons and the Wind River Mountains should be prominently displayed at the Grand Teton National Park Visitor Center. Their stark but quintessentially accurate views provide a welcome alternative to the romantic paintings by lesser artists of the valley, even those of that often celebrated painter, William Robinson Leigh, a colorist who painted the Tetons in 1911 and who was clearly influenced by other Moran paintings. Leigh accompanied a Cody, Wyoming, taxidermist on his Teton expeditions. [40]

|

| William H. Holmes was one of the great topographic artists of his time. A member of the 1878 Hayden expedition, Holmes created this panoramic view of The Teton Range from Upper Grosventre Butte. US. Geological Survey (Maps and Panoramas, Twelfth Annual Report of the United States Geological and Geographical Survey of the Territories, 1878). |

Holmes's panoramas also stand in contrast to the popular work of Conrad Schwiering, who for many years was "The Painter on the Square" in Jackson. Honored by the National Cowboy Hall of Fame's Trustees Gold Medal "for your outstanding contribution to Western Art," Schwiering, a pupil of Charles Chapman, mentioned at the outset of this section, is an impressionist who has probably painted more than 500 Jackson Hole and Teton Mountain scenes. [41] He never tired of painting the Tetons because, due to changing light values and seasons, the mountains are "never static." Indeed, if one spends enough time studying the Tetons, they come to remind one of Japan's sacred Mount Fujiyama; they change colors from the time the mists rise in the morning until the evening sun sets upon them. Japanese artists never tire of painting Mount Fuji, while painters like Schwiering have to explain their fascination with the Tetons. From his gallery at the Wort Hotel in the center of Jackson, especially during its gambling heyday, Schwiering sold his paintings to countless celebrities and movie stars as well as tourists, just as Hank Crandall sold many a painting to the dudes of the twenties and thirties. As recently as August 29, 1997, modernist cowboy artist, Bill Schenck, opened his "The Teton Series" at the Martin Harris Gallery in Jackson. Schenck, who specializes in irony, painted Donald Duck against a stage-painted Tetons background, suggesting a theme of post-modern unreality.

Perhaps the dean of all so-called "cowboy artists" was John Clymer who, recently deceased, was a long time resident of Teton Village. Clymer's later works were history paintings, and one who is knowledgeable of his work cannot cross the bridge over the Snake River on the road to Wilson without noticing the familiar Snake River sandbar upon which Clymer placed a series of stages of composition (one sketch after another, adding more detail each time) of his painting of the mountain men heading up the "Platte River" [sic] to illustrate to students just how he went about composing his western history paintings. He was a generous man and history painters like Tom Lovell and Kenneth Riley are in his debt as are movie makers of a certain era. [42]

|

| Donald Buys the Rubber Snake Ranch by Bill Schenck. Schenck, who specializes in irony, painted Donald Duck against a stage-painted Tetons background. Bill Schenck |

Hollywood and the motion picture, as well as the television industry, provided still another picturing of Jackson Hole. Because of the gleaming snow-covered freshness of the Tetons, countless television commercials have been filmed in the region. One of the most notable was an Old Milwaukee beer commercial. The film makers sent out a casting call for "authentic-looking Jackson Hole fishermen." As one newspaperman put it, "Looking for fishermen in Jackson Hole is like looking for criminals in the state pen." [43] Hundreds of locals immediately auditioned. None of them looked just right. The director, weary of screening virtually the whole male population, finally found the right outdoorsman. Dan Woodward at the Jackson National Fish Hatchery would be, as the paper put it, "the leading man." The two other "stars" were Breck O'Neill, a stuntman and his downstairs neighbor, Todd Link. Clearly, the real thing wouldn't do.

This theme of pseudo-authenticity was carried forward on many interesting levels. The big scene (a 30-second clip) was shot at sunset at Oxbow Bend of the Snake River. It purported to be dawn in the commercial. Then, because Jackson Hole fish were not photogenic enough, the film company imported 50 huge yellowbelly cutthroat trout from the Star Valley Trout Ranch in Afton, Wyoming. They were kept in live boxes at a second site on Pacific Creek. The fish were not fed for several days. A large number of them died, and as the report recounted, "the rest were too stressed out to move." So Dale Best, the Fish Hatchery biologist, was ordered to stitch a thin but strong monofilament to the upper lips of several huge fish that had survived. The cameras were lowered underwater and then, just at the right moment, the fish were yanked above the water surface as if by one of the three fishermen. The fish were dubbed "heroes" by the company. An ordinary trout was attached to Woodward's fly and lifted by him into his net. Woodward "caught" several this way and then the big yellowbellied micro-filamented "hero" fish attached to his line, leaped its high dance above the sparkling waters. The artificially dirtied-up rustic-looking fisherman celebrated with, what else, an ice tub full of Old Milwaukee beer at "dawn." As the reporter concluded, "It doesn't get any better than this." It was art. Today it would be called a "neo-constructivist temporary wildlife experience." This artistic experience was shown whenever possible at NFL football game breaks. It only cost about $250,000 to make.

The hazards of filming commercials became apparent during the filming of a Mountain Dew commercial. One tourist complained to the local newspaper that clearing the brush from the shore destroyed the ecosystem and that his female friend, cruising before the cameras in a canvas kayak, had hit the camera platform, turned over and ripped her boat. [44]

More recently, during the 1997 Major League All Star baseball game, a Chevrolet rolled onto the TV screen, the driver's side door opened and the whole Teton Range flowed out—"Like a Rock." Other commercials filmed in Jackson Hole include ones for Jeep, Toyota, Levis, Maxwell House Coffee, and Ski Doo.

As far as dedicated research can tell, filming in Jackson Hole began in 1921 when the valley was only just opened to dudes. The silent film was entitled Nanette of the North, a different story but the title is a play on Robert Flaherty's popular documentary Nanook of the North. The original footage of Nanette perished in a fire. It was reshot in Alaska.

|

| The Cowboy and the Lady, filmed in 1922, was Jackson Hole's first feature film. The movie, which starred Hollywood ingenue Mary Miles Minter, was shot on the old Pederson Ranch on the south side of the Gros Ventre River north of Jackson. Jackson Hole Historical Society and Museum |

Soon after, in 1922, the controversial Hollywood ingenue, Mary Miles Minter showed up as the heroine of The Cowboy and the Lady, Jackson Hole's first feature film. It was shot on the old Pederson Ranch on the south side of the Gros Ventre River north of Jackson. That same year, whether before or after her visit to the valley is not precisely known, the famous director-actor Desmond Taylor was found shot to death. Purportedly her lover, Mary had sent him missives on butterfly stationery that read: "Dearest—I love you—I love you—I love you—xxxxxxxxxx X yours always! Mary." Mary and the actress Mabel Normand (a movie cowgirl from the 101 Ranch) were the prime suspects. Mary, who looked like Mary Pickford and who was on her way to stardom, suddenly found her career ended. Latter day research indicates that Taylor was probably a homosexual and that Mary's mother, Charlotte Shelby, shot him in a jealous rage. Mary married her milkman and lived along with Charlotte in obscurity in Santa Monica. She died on August 5, 1954. The Cowboy and the Lady was her last big film as the star. [45]

In 1930 John Wayne made his movie debut in Raoul Walsh's The Big Trail filmed in Grand Teton National Park. Wayne played a mountain man and Marguerite Churchill was his citified co-star who initially fears him, then rushes to his arms.

|

| The Big Trail (1930) starring John Wayne, which told the story of a settler's wagon train to Oregon, featuring the settlers lowering wagons down this steep cliff into Jackson Hole. Jackson Hole Historical Society |

To keep their wagons from rolling out of control downhill, the settlers reversed the wheels, putting the large wheels on the downslope side and the smaller wheels on the up slope. Ropes tied to the wagons let them down the steep slope slowly, and logs placed at intervals below the front wheels enabled them to negotiate the descent, though some wagons crashed. Hollywood duplicated this descent mode exactly, though several spectacular crash scenes were filmed along Spread Creek to the west of the valley.

Then, after a lapse of ten years, Wallace Beery appeared as the lead in Wyoming. Six years later he appeared as the gruff but lovable co-star of little Margaret O'Brien in Bad Bascomb in 1946, much of it filmed at Teton Pass and near Signal Mountain. Beery, who, like Mary Miles Minter, was born on April Fool's Day, began his work in the movies as Sweedie, a Swedish maid. As a female impersonator he made at least eight Sweedie films including Sweedie's Hopeless Love. They were not westerns. In 1916 he married Gloria Swanson. They were divorced in 1918, long before Beery made his gruff hero films in Jackson Hole. [46]

|

| The 1940 movie Wyoming. some of which was filmed on the shores of Jackson Lake. Jackson Hole Historical Society and Museum |

|

| Wallace Beery, star of Wyoming and Bad Bascomb, liked Jackson Hole so much that he built a cabin on the shores of Jackson Lake below Signal Mountain. Jackson Hole Historical Society and Museum |

Bad Bascomb told the story of the Mormon trek into Jackson Hole where they came over Teton Pass in a rough crossing. During the shooting of the picture many of the cast bunked in the scattered dude ranches. Beery, of course, played a bad man with a heart of gold continually fighting off romantic advances by Marjorie Main. After helping the Mormons fight off an Indian attack, in the end, rather than marry Marjorie Main, Beery goes back to town believing he will be hanged for his "evil" deeds. Beery liked Jackson Hole so much he built a cabin on Jackson Lake below Signal Mountain.

Even though it was the era of the television western, it was 1951 before another major film was made in Jackson Hole. This was The Big Sky, an adaptation of Pulitzer Prize-winning A. B. Guthrie's splendid novel based on the first script that the noted Montana novelist ever wrote. Howard Hawks had purchased the rights to Guthrie's novel, perhaps the best ever written about the mountain men. RKO produced it. The somewhat oddly chosen stars for the movie were an unknown, Dewey Martin, as the hero Boone Caudill, Kirk Douglas as his red-headed friend Jim Deakins, and Elizabeth Threatt as Teal Eye, Boone's Blackfoot Indian wife.

In what promised to be a major film with a triangular love affair, Dudley Nichol's script focused only on the first half of the novel in which Boone kills his redheaded friend Deakins because Teal Eye, his Indian wife, has a redheaded baby. Nichols and Howard Hawks chose to excise the dark parts of Paul Guthrie's tale and concentrate on the positive. They emphasized the "brotherhood" of the mountain men, the French boatmen, the woman Teal Eye and Poordevil, a crazed but comic Indian. The whole thing became a parable of "togetherness." [47]

The real stars of the film are the two exact replicas of the old Missouri River keelboat of the 1820s that the mountain men poled and tugged by ropes up 2,000 miles of the Big Muddy, contending with logs, brush, poison ivy, snakes, wolves and hostile Indians. The best feature of The Big Sky keelboats is their silent motors that make such labor in the movie make believe. One of these boats, that originally cost $28,000 in 1952, has been recently restored by the Montana Historical Society. Much of the film features the keelboat on the Snake River as it came out of Jackson Lake. Menor's historic ferry crossing was another place the boat was filmed. The crew camped in a large tent village near Moran, Wyoming.

|

| The Big Sky, released in 1952, was adapted from A.B. Guthrie's novel. Portions of The Big Sky were filmed at Menor's Ferry. One of the make-believe keelboats used in the movie has been restored by the Montana Historical Society. Jackson Hole Historical Society and Museum |

An anthropologist from the American Museum of Natural History, reviewing The Big Sky found it grossly inaccurate. The keelboat was satisfactory, but birchbark canoes on the Upper Missouri? No. The tipis were furnished with southern Arizona bric-a brac such as Apache baskets, the Blackfeet (actual tribe members) "are portrayed with the same magnificent disregard for fact that we have learned to expect in the average grade-B horse opera," he ejaculated. Teal Eye, the female lead "slinks about in a costume that recalls Minnehaha in a school pageant." The New York anthropologist and some later Indian commentators made the point that to Hollywood all Indians were alike. He concluded "perhaps it is too much to expect that the purveyors of what passes for history in most movies should be aware of them" [the special culture and dress of the Blackfeet] [48] The critic had nothing to say of the casting and acting. He should have. Can the film be remade today?

At the same time, another of Guthrie's scripts was coming to life—Shane. This interpretation of a New Haven, Connecticut, reporter's novel is perhaps the best loved of all the films made in Jackson Hole. Directed by George Stevens, this film, like the unfortunate The Big Sky, aimed to get away from the gun fighter-saloon-girl town western or even the cowboy extravaganza. Realism was said to be the keynote. It was indeed the first film with loud realistic gun shots that startled audiences. Shane is the story of settlers just like those who came into Jackson Hole in the late nineteenth century and the mysterious "Knight Errant" gunman who defends them. Van Heflin starred as hard-working honest Joe Starratt, the settler; Jean Arthur, no glamour girl, played his wife; Ben Johnson, always authentic, played the town bully; Jack Palance played the gunfighter; and Alan Ladd played the mythical samurai who defends the homesteaders, Shane. Brandon de Wilde as the child, Joey Starratt, almost stole the show. One can still hear him calling "Shane, Shane, Shane," as the wounded Alan Ladd rides out of their lives and into the Tetons. While realistic, Shane had much of the mythical about it to which the slow-moving reptilian gunfighter Jack Palance contributed a great deal, as did the paradise scenery of the Tetons and Jackson Hole itself.

|

| Alan Ladd and Jean Arthur in Shane, which was made in 1953 and is one of the most popular movies filmed in Jackson Hole. Jackson Hole Historical Society and Museum |

Most visitors to the park want to see the Shane sets and locations. Alas, the rude town with its saloon and general store is now long gone from Antelope Flats. A slowly crumbling homestead cabin, the Luther Taylor Homestead with a Teton Mountain background, still remains. So does Mormon Row and Schwabacher's Landing where the homesteaders crossed the river to reach the town. The Ernie Wright Cabin near Kelly Warm Springs was also used as the Starratt Homestead, though a complete interior of the cabin was built inside the unfinished Jackson Hole High School. Teton Valley Ranch, on the Gros Ventre, also figured in the film. It is to some a significant question as to whether some of the Shane cabins should be restored, though the local authority on the subject of their location has not committed himself. [49] Restoration of early settlers' cabins and dude ranches sometimes runs counter to the philosophy of Grand Teton National Park, though one notes on the U.S.G.S. and the National Geographical Society official topographical maps that not far from Jackson, near Miller Springs, is the historic Miller Cabin, where Teton Jackson, the notorious outlaw, holed up. [50]

|

| The town set for Shane once stood on Antelope Flats. Jackson Hole Historical Society and Museum |

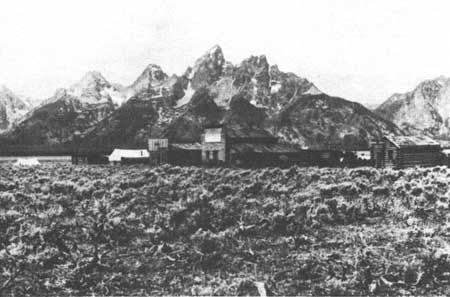

Spencer's Mountain, made in 1963, also caused a stir. It starred Henry Fonda who was variously termed "a great guy, very down to earth" and a bad interview. Maureen O'Hara, James McArthur and Mimsy Farmer were also in the film about a boy, oddly named Clayboy, growing into manhood in a poor homesteader family, grateful for the chance to go off to college where he will be with blonde beauty Mimsy Farmer, his first love. It is a story of family sacrifice that became a TV series, The Waltons.

Spencer's Mountain was filmed primarily near Triangle X Ranch, not far from the Cunningham Cabin. As one writer put it for the Jackson Hole Gazette, "The hill behind Triangle X Ranch may have had another name once, but the Turners of the Triangle X Ranch call it "Spencer's Mountain." [51] From it one could look far across the flats and Jenny Lake to the Tetons in the distance. Actually the Triangle X was the same location where Jubal, starring Glenn Ford and Ernest Borgnine, was made in 1956. Fonda, between takes for Spencer's Mountain, went fishing only to get a hook in his eyelid. So great was the Jackson Hole hysteria about Spencer's Mountain that someone wrote that "Henry Fonda milked a cow in the Moulton Barn!"

In 1969, the Hunter Hereford Ranch, the Twin Creek Ranch, Teton Valley Ranch, and Brooks Lake were the settings for The Wild Country, released in 1971. The movie starred Steve Forrest, Vera Miles, and Ron Howard. It is the story of a pioneer family that moves west from Pittsburgh, homesteads and, as in Shane, is forced to fight the cattlemen. On the Hunter Hereford Ranch the town of Kelly, washed away in a flood in 1927, was reconstructed and the old Moulton Cabin was moved to the Twin Creek Ranch to serve as the family homestead. Today the Hunter Hereford Ranch still stands in good condition, one side of the barn altered by the filmmakers to look antique. The hay shed and stud barn were also remodeled to serve as movie props. Hollywood added Greek Revival windows to the north side of the hay shed so that it could serve as a movie-set church. The cabin and stable still stand, used to store equipment, and a lone buffalo calls the ranch home.

As of 1993 there had been a number of more or less significant films made or partially made in Jackson Hole, including Sylvester Stallone's Rocky IV, the video releases for Dances With Wolves, Lakota Moon (an all-Indian film pilot made in 1991 but never released), Clint Eastwood's Any Which Way You Can, The Wrong Guys and small parts of James Michener's Centennial. Much of Dream West, a TV series starring Richard Chamberlain as Lt. John C. Fremont, who never saw Jackson Hole but did climb a high peak in the Wind River Mountains that he named for himself was made in the valley. Another TV series of the 1960s, The Monroes, was the story of five orphaned children, the oldest of whom is played by the fresh and beautiful Barbara Hershey. She was the star, along with her Great Pyrenees dog, Snow. However, in the atmosphere of the sixties, the series was too wholesome. It had a short run. Another wholesome production of the nineties, however, A River Runs Through It, was partially filmed in Jackson Hole. The famous falls sequence was filmed on Fall Creek, not the Yellowstone.

Some of the other significant motion pictures were early silent films such as Charge of the Light Brigade (1912), The Man From Panted Post (1917) starring Douglas Fairbanks and Hoot Gibson, Indian Life (1917) with an all Indian cast, and The Thundering Herd (1924) by Famous Players Laskey, starring Tim McCoy (Yellowstones first park ranger), Noah Beery and Gary Cooper.

Later, more famous films included The Plainsman (1937) starring Gary Cooper and Jean Arthur, Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977), Pow Wow Highway (1989) which was also shot on or near the Lame Deer Reservation in northeastern Wyoming, The Vanishing (1993), a Jeff Bridges, Sandra Bullock extravaganza, and Christmas in Connecticut (1992). [52]

|

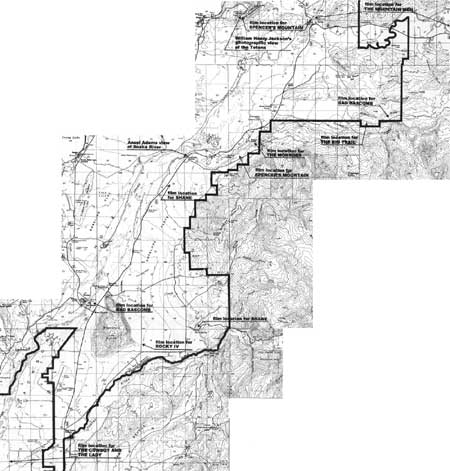

| Photograph and film locations in the Jackson area. (click on the image for an enlargement in a new window) U.S. Geological Survey |

One film made in and around Jackson Hole in 1979 that curiously has not received enough praise is Charleton Heston's The Mountain Men, which also starred the late Brian Keith. This picture, perhaps the best one ever filmed in Jackson Hole, made by far the best use of its scenic possibilities, from the opening credits which feature the Tetons and Jackson Lake, to many locations along the Snake River, as well as the higher fields near Triangle X Ranch east of the river. Some spectacular sequences were filmed in Yellowstone's geyser basins, others at the foot of the Togwotee Pass in five feet of snow. It is also an authentic film that recreates an uproarious mountain man rendezvous on the Triangle X Ranch. This scene, filmed over a two-week period, required the construction of 80 tipis, rows of tents for fur traders, wagons, a corral, fire sites and extraordinary costuming for a large number of people. Many of the 500 "mountain men" who participated in the rendezvous scene were recruited from mountain man re-enactment clubs all over the country. The Indians were recruited from the Wind River Reservation, Fort Hall, Idaho, and Ogalalla, Nebraska. The script was written by Charleton Heston's son, Frazer, himself an expert on mountain man history. Many of the scenes bring the history paintings of John Clymer, Tom Lovell, Kenneth Riley and Frank McCarthy to life. [53]

Perhaps it was too authentic, too historical for audiences of the 1970s. Now, however, many prefer their history as pseudo-authentic documentaries like Ken Burns's recent TV series, The West, partly filmed in Jackson Hole and loaded with politically correct messages and talking heads as well as many gaffes such as photographs of Coronado and the leaders of the 1680 Pueblo Revolt.

One wonders, has the documentary with expert authenticators as talking heads taken the place of historically-oriented feature films? What of the Old West and its history where, in 1928, Owen Wister, the prolific author Struthers Burt, and Ernest Hemingway, completing a draft of his very modernist book, A Farewell to Arms, could still fish the Snake and appreciate rustic living on Burt's Three Rivers Ranch, with its jerry-built dude cabins with sod roofs and homemade furniture? Then it was a dude-ranch paradise in which even the fastidious publisher Alfred A. Knopf reveled. It was where Wallace Stegner and Bernard DeVoto tried to blend the Old West with the new. Have Jackson Hole's human inhabitants either turned banal, contemporary or disappeared? Is Jackson Hole too scenic, too identifiable for modern film makers who prefer road films, urban dramas where the Mafia reigns, stories of serial killers, or Stephen Spielberg's special effects movies? Are we tuned toward the vast universe of Contact, in which case Jackson Hole is too small, its historic past too brief. [54] In addition, the park's relentless return to a pristine, non-human ecosystem seems the wave of the future as few of the picture makers now look back. The tourists and environmentalists are mostly into nature and its destruction by "rapacious" alien humans, not the settlers' era portrayed in Shane and Spencer's Mountain. For Jackson Hole and its temporary historical denizens substitute Zabriski Point in Death Valley and the Nevada Atomic Test Sites as we follow the avant garde picture makers of a West that is no longer ours.

|

| The Moulton Barn, with the majestic Teton Range in the background, is popular with photographers. The barn is located on Mormon Row. Roger Whitacre |

Postscript

The National Park Service's "nature only" policy has largely effaced Jackson Hole's historic dimension. Famous dude ranches, as well as the barns and cabins used in film making, are being left to molder away. This has caused some controversy. Struthers Burt sold his ranch, the Bar BC, and Nathaniel Burt sold the Three Rivers Ranch at cost to the Rockefeller Snake River Land Company, and they thus became part of the Grand Teton National Park. Both Burts, strong advocates of the Rockefeller expansion of the park, felt it was their patriotic duty. As they and others lived on at the Three Rivers Ranch as lessees under the terms of sale, neither father nor son envisioned the destruction of the ranches. They believed them to be historic sites, not only because famous people like the publisher Alfred Knopf who served on the National Park Service Advisory Board, had stayed there, but also because of the distinctive vernacular architecture of the ranch buildings. [55] Nathaniel Burt felt, and Roy Graham Associates, a restoration architectural firm who made an assessment in 1994, felt that the Bar BC Ranch buildings of Burt's first dude ranch were part of the landscape. Listed on the National Register of Historic Places, they should be properly cared for and, if necessary, restored though at some, possibly donor, expense. [56] An offer of funding for restoration purposes with respect to the Three Rivers Ranch was offered by Burt's son, Nathaniel. [57] His offer was rejected. Some buildings were moved, and the rest, owned by the National Park Service, were demolished. In an era where American history is being severely distorted for political purposes, it does seem important that some vestiges of the past remain—some evidence of the staying power of the pioneer past and the romantic cowboy past—even into the mid-twentieth century. The buildings and the furniture of the Bar BC, which is still standing, were made on the ranch; the stone chimneys were constructed with stones from the Snake River by an amateur local builder. It represents a time before the pre-fabricated age and, to an historian and even a tourist, the Bar BC Ranch, while not a work of art, is a work of interest—a sight to be seen and interpreted, as are some of the remaining structures from the era of motion picture making. To many people the Old West is the West and Jackson Hole, with its colorful setting and history, should probably be more interesting than one's hometown hike-and-bike trail or a ski resort. Keeping in touch with the past is keeping in touch with nature in all its varied forms.

Notes

1. On June 11, 1942, Ansel Adams wrote to Nancy Newhall that he was heading to Billings, Montana, "then to Yellowstone, then to Glacier, then on west to Rainier and Crater Lake, then home." He was on a Harold Ickes-inspired National Parks assignment. Adams apparently changed his itinerary to include Jackson Hole, the Tetons and the Snake River Valley. Just at that time, however, Franklin Delano Roosevelt and the National Park Service were in a furious battle with the ranchers at Jackson Hole over young John D. Rockefeller Jr.'s secret purchases of land with the Snake River Land Company as a front. Rockefeller intended to give his huge parcel of Teton Valley to the National Park Service. The cattlemen, Wyoming congressmen and senators, local politicians and the U.S. Forest Service all objected. The movie actor and valley resident, Wallace Beery, led an armed posse and a herd of cattle across park land. Fortunately, the National Park Service ignored the opera bouffé gesture and no shootouts occurred.

With this heated conflict brewing, it appears that Ansel Adams detoured from Yellowstone into Jackson Hole and made his photograph The Tetons and the Snake River, Grand Teton National Park that included much land that Rockefeller intended to give for park expansion. Taken in a rainstorm, it was a majestic photograph that clearly touted the vast emptiness of unspoiled nature. Was it also meant as one of Interior Secretary Ickes's public appeal weapons in the war with the ranchers and the Forest Service over which he had no control? This would explain Adams's change of itinerary, See Ansel Adams, Letters and Images 1916-1984 (Boston: Little, Brown and Co., 1988), p. 135; and Betts, Along the Ramparts, Chapter 18; for Beery's action, see p. 209. Also see Righter, Crucible for Conservation, passim, especially pp. 114-115.

Ansel Adams himself said "I do not recall that I ever intentionally made a photograph for environmentally significant purposes"—this despite the fact that his photographs appeared regularly in Sierra Club books and calendars. Quoted in Robert Bednar, "Postmodern Vistas, Landscapes, Photography, and Tourism in the Contemporary American West," unpublished dissertation, University of Texas, Austin, American Civilization Program, 1997, pp. 145-146.

2. Righter, Crucible for Conservation, pp. 126-152; and author's personal inspection of the Bar BC Ranch, June 25, 1997.

3. Betts, Along the Ramparts, p. 147.

4. Ibid, p. 152. For the Spencer and Burnett killings, see Frank Calkins, Jackson Hole (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1973), pp. 122-123.

5. For examples of the maps mentioned here, see Carl I. Wheat, Mapping the Transmississippi West, 1540-1861, 5 vols. (San Francisco: The Institute of Historical Cartography, 1958), vol. 2. For Lewis and Clark, opposite p. 56, for Chevelier Lapie, pp. 73-76, Aaron Arrowsmith, opposite p. 148, Capt. B. L. E. Bonneville, opposite p. 158, Capt. Washington Hood, opposite p. 160, Warren Ferris, opposite p. 156, Fremont, Gibbs Smith, opposite p. 128, but also see pp. 119-139. For Jim Bridger's map, see Goetzmann, Exploration and Empire, p. 119. The original map is at the Wyoming Heritage Center, Laramie, Wyoming.

6. Betts, Along the Ramparts, p. 59.

7. Report on the Exploration of the Yellowstone River, by Brevet Brigadier General, W. F. Raynolds (40th Congress 1st Session, Senate Executive Document No. 77, 1868). Also see Mary C. Withington, A Catalogue of Manuscripts in the Collection of Western Americana Founded by William Robertson Coe, Yale University Library (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1952) entry 393, pp. 214-217, in which she states that Yale has three watercolors, six pen and ink sketches, three pencil sketches, 41 photographs of paintings and sketches, and six photographs from the Raynolds expedition. For Schonborn's suicide, see Goetzmann, p. 503. J. D. Hutton did make two pencil sketches of the Tetons that are at Yale. Three early photo reproductions of sketches of the Snake River and the Tetons by Schonborn and one pen and ink drawing by Raynolds are in the Western Americana Collection of the Beinecke Library at Yale.