|

Personal Justice Denied

|

SUMMARY

The Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians was established by act of Congress in 1980 and directed to

1. review the facts and circumstances surrounding Executive Order Numbered 9066, issued February 19, 1942, and the impact of such Executive Order on American citizens and permanent resident aliens;

2. review directives of United States military forces requiring the relocation and, in some cases, detention in internment camps of American citizens, including Aleut civilians, and permanent resident aliens of the Aleutian and Pribilof Islands; and

3. recommend appropriate remedies.

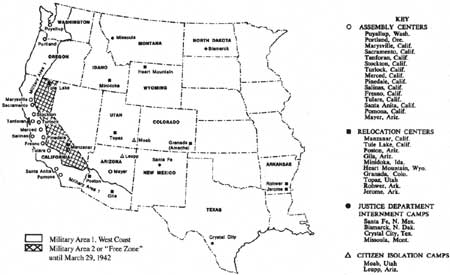

Map reprinted from Michi Weglyn, Years of Infamy (1976), by kind

permission of William Morrow & Company, Inc. (click on image for

an enlargement in a new window)

In fulfilling this mandate, the Commission held 20 days of hearings in cities across the country, particularly on the West Coast, hearing testimony from more than 750 witnesses: evacuees, former government officials, public figures, interested citizens, and historians and other professionals who have studied the subjects of Commission inquiry. An extensive effort was made to locate and to review the records of government action and to analyze other sources of information including contemporary writings, personal accounts and historical analyses.

By presenting this report to Congress, the Commission fulfills the instruction to submit a written report of its findings. Like the body of the report, this summary is divided into two parts. The first describes actions taken pursuant to Executive Order 9066, particularly the treatment of American citizens of Japanese descent and resident aliens of Japanese nationality. The second covers the treatment of Aleuts from the Aleutian and Pribilof Islands.

PART I: NISEI AND ISSEI*

On February 19, 1942, ten weeks after the Pearl Harbor attack, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, which gave to the Secretary of War and the military commanders to whom he delegated authority, the power to exclude any and all persons, citizens and aliens, from designated areas in order to provide security against sabotage, espionage and fifth column activity. Shortly thereafter, all American citizens of Japanese descent were prohibited from living, working or traveling on the West Coast of the United States. The same prohibition applied to the generation of Japanese immigrants who, pursuant to federal law and despite long residence in the United States, were not permitted to become American citizens. Initially, this exclusion was to be carried out by "voluntary" relocation. That policy inevitably failed, and these American citizens and their alien parents were removed by the Army, first to "assembly centers"—temporary quarters at racetracks and fairgrounds—and then to "relocation centers"—bleak barrack camps mostly in desolate areas of the West. The camps were surrounded by barbed wire and guarded by military police. Departure was permitted only after a loyalty review on terms set, in consultation with the military, by the War Relocation Authority, the civilian agency that ran the camps. Many of those removed from the West Coast were eventually allowed to leave the camps to join the Army, go to college outside the West Coast or to whatever private employment was available. For a larger number, however, the war years were spent behind barbed wire; and for those who were released, the prohibition against returning to their homes and occupations on the West Coast was not lifted until December 1944.

*The first generation of ethnic Japanese born in the United states are Nisei; the Issei are the immigrant generation from Japan; and those who returned to Japan as children for education are Kibei.

This policy of exclusion, removal and detention was executed against 120,000 people without individual review, and exclusion was continued virtually without regard for their demonstrated loyalty to the United States. Congress was fully aware of and supported the policy of removal and detention; it sanctioned the exclusion by enacting a statute which made criminal the violation of orders issued pursuant to Executive Order 9066. The United States Supreme Court held the exclusion constitutionally permissible in the context of war, but struck down the incarceration of admittedly loyal American citizens on the ground that it was not based on statutory authority.

All this was done despite the fact that not a single documented act of espionage, sabotage or fifth column activity was committed by an American citizen of Japanese ancestry or by a resident Japanese alien on the West Coast.

No mass exclusion or detention, in any part of the country, was ordered against American citizens of German or Italian descent. Official actions against enemy aliens of other nationalities were much more individualized and selective than those imposed on the ethnic Japanese.

The exclusion, removal and detention inflicted tremendous human cost. There was the obvious cost of homes and businesses sold or abandoned under circumstances of great distress, as well as injury to careers and professional advancement. But, most important, there was the loss of liberty and the personal stigma of suspected disloyalty for thousands of people who knew themselves to be devoted to their country's cause and to its ideals but whose repeated protestations of loyalty were discounted—only to be demonstrated beyond any doubt by the record of Nisei soldiers, who returned from the battlefields of Europe as the most decorated and distinguished combat unit of World War II, and by the thousands of other Nisei who served against the enemy in the Pacific, mostly in military intelligence. The wounds of the exclusion and detention have healed in some respects, but the scars of that experience remain, painfully real in the minds of those who lived through the suffering and deprivation of the camps.

The personal injustice of excluding, removing and detaining loyal American citizens is manifest. Such events are extraordinary and unique in American history. For every citizen and for American public life, they pose haunting questions about our country and its past. It has been the Commission's task to examine the central decisions of this history—the decision to exclude, the decision to detain, the decision to release from detention and the decision to end exclusion. The Commission has analyzed both how and why those decisions were made, and what their consequences were. And in order to illuminate those events, the mainland experience was compared to the treatment of Japanese Americans in Hawaii and to the experience of other Americans of enemy alien descent, particularly German Americans.

The Decision to Exclude

The Context of the Decision. First, the exclusion and removal were attacks on the ethnic Japanese which followed a long and ugly history of West Coast anti-Japanese agitation and legislation. Antipathy and hostility toward the ethnic Japanese was a major factor of the public life of the West Coast states for more than forty years before Pearl Harbor. Under pressure from California, immigration from Japan had been severely restricted in 1908 and entirely prohibited in 1924. Japanese immigrants were barred from American citizenship, although their children born here were citizens by birth. California and the other western states prohibited Japanese immigrants from owning land. In part the hostility was economic, emerging in various white American groups who began to feel competition, particularly in agriculture, the principal occupation of the immigrants. The anti-Japanese agitation also fed on racial stereotypes and fears: the "yellow peril" of an unknown Asian culture achieving substantial influence on the Pacific Coast or of a Japanese population alleged to be growing far faster than the white population. This agitation and hostility persisted, even though the ethnic Japanese never exceeded three percent of the population of California, the state of greatest concentration.

The ethnic Japanese, small in number and with no political voice—the citizen generation was just reaching voting age in 1940—had become a convenient target for political demagogues, and over the years all the major parties indulged in anti-Japanese rhetoric and programs. Political bullying was supported by organized interest groups who adopted anti-Japanese agitation as a consistent part of their program: the Native Sons and Daughters of the Golden West, the Joint Immigration Committee, the American Legion, the California State Federation of Labor and the California State Grange.

This agitation attacked a number of ethnic Japanese cultural traits or patterns which were woven into a bogus theory that the ethnic Japanese could not or would not assimilate or become "American." Dual citizenship, Shinto, Japanese language schools, and the education of many ethnic Japanese children in Japan were all used as evidence. But as a matter of fact, Japan's laws on dual citizenship went no further than those of many European countries in claiming the allegiance of the children of its nationals born abroad. Only a small number of ethnic Japanese subscribed to Shinto, which in some forms included veneration of the Emperor. The language schools were not unlike those of other first-generation immigrants, and the return of some children to Japan for education was as much a reaction to hostile discrimination and an uncertain future as it was a commitment to the mores, much less the political doctrines, of Japan. Nevertheless, in 1942 these popular misconceptions infected the views of a great many West Coast people who viewed the ethnic Japanese as alien and unassimilated.

Second, Japanese armies in the Pacific won a rapid, startling string of victories against the United States and its allies in the first months of World War II. On the same day as the attack on Pearl Harbor, the Japanese struck the Malay Peninsula, Hong Kong, Wake and Midway Islands and attacked the Philippines. The next day the Japanese Army invaded Thailand. On December 13 Guam fell; on December 24 and 25 the Japanese captured Wake Island and occupied Hong Kong. Manila was evacuated on December 27, and the American army retreated to the Bataan Peninsula. After three months the troops isolated in the Philippines were forced to surrender unconditionally—the worst American defeat since the Civil War. In January and February 1942, the military position of the United States in the Pacific was perilous. There was fear of Japanese attacks on the West Coast.

Next, contrary to the facts, there was a widespread belief, supported by a statement by Frank Knox, Secretary of the Navy, that the Pearl Harbor attack had been aided by sabotage and fifth column activity by ethnic Japanese in Hawaii. Shortly after Pearl Harbor the government knew that this was not true, but took no effective measures to disabuse public belief that disloyalty had contributed to massive American losses on December 7, 1941. Thus the country was unfairly led to believe that both American citizens of Japanese descent and resident Japanese aliens threatened American security.

Fourth, as anti-Japanese organizations began to speak out and rumors from Hawaii spread, West Coast politicians quickly took up the familiar anti-Japanese cry. The Congressional delegations in Washington organized themselves and pressed the War and Justice Departments and the President for stern measures to control the ethnic Japanese—moving quickly from control of aliens to evacuation and removal of citizens. In California, Governor Olson, Attorney General Warren, Mayor Bowron of Los Angeles and many local authorities joined the clamor. These opinions were not informed by any knowledge of actual military risks, rather they were stoked by virulent agitation which encountered little opposition. Only a few churchmen and academicians were prepared to defend the ethnic Japanese. There was little or no political risk in claiming that it was "better to be safe than sorry" and, as many did, that the best way for ethnic Japanese to prove their loyalty was to volunteer to enter detention. The press amplified the unreflective emotional excitement of the hour. Through late January and early February 1942, the rising clamor from the West Coast was heard within the federal government as its demands became more draconian.

Making and Justifying the Decision. The exclusion of the ethnic Japanese from the West Coast was recommended to the Secretary of War, Henry L. Stimson, by Lieutenant General John L. DeWitt, Commanding General of the Western Defense Command with responsibility for West Coast security. President Roosevelt relied on Secretary Stimson's recommendations in issuing Executive Order 9066.

The justification given for the measure was military necessity. The claim of military necessity is most clearly set out in three places: General DeWitt's February 14, 1942, recommendation to Secretary Stimson for exclusion; General DeWitt's Final Report: Japanese Evacuation from the West Coast, 1942; and the government's brief in the Supreme Court defending the Executive Order in Hirabayashi v. United States. General DeWitt's February 1942 recommendation presented the following rationale for the exclusion:

In the war in which we are now engaged racial affinities are not severed by migration. The Japanese race is an enemy race and while many second and third generation Japanese born on United States soil, possessed of United States citizenship, have become "Americanized," the racial strains are undiluted. To conclude otherwise is to expect that children born of white parents on Japanese soil sever all racial affinity and become loyal Japanese subjects, ready to fight and, if necessary, to die for Japan in a war against the nation of their parents. That Japan is allied with Germany and Italy in this struggle is no ground for assuming that any Japanese, barred from assimilation by convention as he is, though born and raised in the United States, will not turn against this nation when the final test of loyalty comes. It, therefore, follows that along the vital Pacific Coast over 112,000 potential enemies, of Japanese extraction, are at large today. There are indications that these were organized and ready for concerted action at a favorable opportunity. The very fact that no sabotage has taken place to date is a disturbing and confirming indication that such action will be taken.

There are two unfounded justifications for exclusion expressed here: first, that ethnicity ultimately determines loyalty; second, that "indications" suggest that ethnic Japanese "are organized and ready for concerted action"—the best argument for this being the fact that it hadn't happened.

The first evaluation is not a military one but one for sociologists or historians. It runs counter to a basic premise on which the American nation of immigrants is built—that loyalty to the United States is a matter of individual choice and not determined by ties to an ancestral country. In the case of German Americans, the First World War demonstrated that race did not determine loyalty, and no negative assumption was made with regard to citizens of German or Italian descent during the Second World War. The second judgment was, by the General's own admission, unsupported by any evidence. General DeWitt's recommendation clearly does not provide a credible rationale, based on military expertise, for the necessity of exclusion.

In his 1943 Final Report, General DeWitt cited a number of factors in support of the exclusion decision: signaling from shore to enemy submarines; arms and contraband found by the FBI during raids on ethnic Japanese homes and businesses; dangers to the ethnic Japanese from vigilantes; concentration of ethnic Japanese around or near militarily sensitive areas; the number of Japanese ethnic organizations on the coast which might shelter pro-Japanese attitudes or activities such as Emperor-worshipping Shinto; and the presence of the Kibei, who had spent some time in Japan.

The first two items point to demonstrable military danger. But the reports of shore-to-ship signaling were investigated by the Federal Communications Commission, the agency with relevant expertise, and no identifiable cases of such signaling were substantiated. The FBI did confiscate arms and contraband from some ethnic Japanese, but most were items normally in the possession of any law-abiding civilian, and the FBI concluded that these searches had uncovered no dangerous persons that "we could not otherwise know about." Thus neither of these "facts" militarily justified exclusion.

There had been some acts of violence against ethnic Japanese on the West Coast and feeling against them ran high, but "protective custody" is not an acceptable rationale for exclusion. Protection against vigilantes is a civilian matter that would involve the military only in extreme cases. But there is no evidence that such extremity had been reached on the West Coast in early 1942. Moreover, "protective custody" could never justify exclusion and detention for months and years.

General DeWitt's remaining points are repeated in the Hirabayashi brief, which also emphasizes dual nationality, Japanese language schools and the high percentage of aliens (who, by law, had been barred from acquiring American citizenship) in the ethnic population. These facts represent broad social judgments of little or no military significance in themselves. None supports the claim of disloyalty to the United States and all were entirely legal. If the same standards were applied to other ethnic groups, as Morton Grodzins, an early analyst of the exclusion decision, applied it to ethnic Italians on the West Coast, an equally compelling and meaningless case for "disloyalty" could be made. In short, these social and cultural patterns were not evidence of any threat to West Coast military security.

In sum, the record does not permit the conclusion that military necessity warranted the exclusion of ethnic Japanese from the West Coast.

The Conditions Which Permitted the Decision. Having concluded that no military necessity supported the exclusion, the Commission has attempted to determine how the decision came to be made.

First, General DeWitt apparently believed what he told Secretary Stimson: ethnicity determined loyalty. Moreover, he believed that the ethnic Japanese were so alien to the thought processes of white Americans that it was impossible to distinguish the loyal from the disloyal. On this basis he believed them to be potential enemies among whom loyalty could not be determined.

Second, the FBI and members of Naval Intelligence who had relevant intelligence responsibility were ignored when they stated that nothing more than careful watching of suspicious individuals or individual reviews of loyalty were called for by existing circumstances. In addition, the opinions of the Army General Staff that no sustained Japanese attack on the West Coast was possible were ignored.

Third, General DeWitt relied heavily on civilian politicians rather than informed military judgments in reaching his conclusions as to what actions were necessary, and civilian politicians largely repeated the prejudiced, unfounded themes of anti-Japanese factions and interest groups on the West Coast.

Fourth, no effective measures were taken by President Roosevelt to calm the West Coast public and refute the rumors of sabotage and fifth column activity at Pearl Harbor.

Fifth, General DeWitt was temperamentally disposed to exaggerate the measures necessary to maintain security and placed security far ahead of any concern for the liberty of citizens.

Sixth, Secretary Stimson and John J. McCloy, Assistant Secretary of War, both of whose views on race differed from those of General DeWitt, failed to insist on a clear military justification for the measures General DeWitt wished to undertake.

Seventh, Attorney General Francis Biddle, while contending that exclusion was unnecessary, did not argue to the President that failure to make out a case of military necessity on the facts would render the exclusion constitutionally impermissible or that the Constitution prohibited exclusion on the basis of ethnicity given the facts on the West Coast.

Eighth, those representing the interests of civil rights and civil liberties in Congress, the press and other public forums were silent or indeed supported exclusion. Thus there was no effective opposition to the measures vociferously sought by numerous West Coast interest groups, politicians and journalists.

Finally, President Roosevelt, without raising the question to the level of Cabinet discussion or requiring any careful or thorough review of the situation, and despite the Attorney General's arguments and other information before him, agreed with Secretary Stimson that the exclusion should be carried out.

The Decision to Detain

With the signing of Executive Order 9066, the course of the President and the War Department was set: American citizens and alien residents of Japanese ancestry would be compelled to leave the West Coast on the basis of wartime military necessity. For the War Department and the Western Defense Command, the problem became primarily one of method and operation, not basic policy. General DeWitt first tried "voluntary" resettlement: the ethnic Japanese were to move outside restricted military zones of the West Coast but otherwise were free to go wherever they chose. From a military standpoint this policy was bizarre, and it was utterly impractical. If the ethnic Japanese had been excluded because they were potential saboteurs and spies, any such danger was not extinguished by leaving them at large in the interior where there were, of course, innumerable dams, power lines, bridges and war industries to be disrupted or spied upon. Conceivably sabotage in the interior could be synchronized with a Japanese raid or invasion for a powerful fifth column effect. This raises serious doubts as to how grave the War Department believed the supposed threat to be. Indeed, the implications were not lost on the citizens and politicians of the interior western states, who objected in the belief that people who threatened wartime security in California were equally dangerous in Wyoming and Idaho.

The War Relocation Authority (WRA), the civilian agency created by the President to supervise the relocation and initially directed by Milton Eisenhower, proceeded on the premise that the vast majority of evacuees were law-abiding and loyal, and that, once off the West Coast, they should be returned quickly to conditions approximating normal life. This view was strenuously opposed by the people and politicians of the mountain states. In April 1942, Milton Eisenhower met with the governors and officials of the mountain states. They objected to California using the interior states as a "dumping ground" for a California "problem." They argued that people in their states were so bitter over the voluntary evacuation that unguarded evacuees would face physical danger. They wanted guarantees that the government would forbid evacuees to acquire land and that it would remove them at the end of the war. Again and again, detention camps for evacuees were urged. The consensus was that a plan for reception centers was acceptable so long as the evacuees remained under guard within the centers.

In the circumstances, Milton Eisenhower decided that the plan to move the evacuees into private employment would be abandoned, at least temporarily. The War Relocation Authority dropped resettlement and adopted confinement. Notwithstanding WRA's belief that evacuees should be returned to normal productive life, it had, in effect, become their jailer. The politicians of the interior states had achieved the program of detention.

The evacuees were to be held in camps behind barbed wire and released only with government approval. For this course of action no military justification was proffered. Instead, the WRA contended that these steps were necessary for the benefit of evacuees and that controls on their departure were designed to assure they would not be mistreated by other Americans on leaving the camps.

It follows from the conclusion that there was no justification in military necessity for the exclusion, that there was no basis for the detention.

The Effect of the Exclusion and Detention

The history of the relocation camps and the assembly centers that preceded them is one of suffering and deprivation visited on people against whom no charges were, or could have been, brought. The Commission hearing record is full of poignant, searing testimony that recounts the economic and personal losses and injury caused by the exclusion and the deprivations of detention. No summary can do this testimony justice.

Families could take to the assembly centers and the camps only what they could carry. Camp living conditions were Spartan. People were housed in tar-papered barrack rooms of no more than 20 by 24 feet. Each room housed a family, regardless of family size. Construction was often shoddy. Privacy was practically impossible and furnishings were minimal. Eating and bathing were in mass facilities. Under continuing pressure from those who blindly held to the belief that evacuees harbored disloyal intentions, the wages paid for work at the camps were kept to the minimal level of $12 a month for unskilled labor, rising to $19 a month for professional employees. Mass living prevented normal family communication and activities. Heads of families, no longer providing food and shelter, found their authority to lead and to discipline diminished.

The normal functions of community life continued but almost always under a handicap—doctors were in short supply; schools which taught typing had no typewriters and worked from hand-me-down school books; there were not enough jobs.

The camp experience carried a stigma that no other Americans suffered. The evacuees themselves expressed the indignity of their conditions with particular power:

On May 16, 1942, my mother, two sisters, niece, nephew, and I left . . . by train. Father joined us later. Brother left earlier by bus. We took whatever we could carry. So much we left behind, but the most valuable thing I lost was my freedom.

* * *

Henry went to the Control Station to register the family. He came home with twenty tags, all numbered 10710, tags to be attached to each piece of baggage, and one to hang from our coat lapels. From then on, we were known as Family #10710.

The government's efforts to "Americanize" the children in the camps were bitterly ironic:

An oft-repeated ritual in relocation camp schools . . . was the salute to the flag followed by the singing of "My country, 'tis of thee, sweet land of liberty"—a ceremony Caucasian teachers found embarrassingly awkward if not cruelly poignant in the austere prison-camp setting.

* * *

In some ways, I suppose, my life was not too different from a lot of kids in America between the years 1942 and 1945. I spent a good part of my time playing with my brothers and friends, learned to shoot marbles, watched sandlot baseball and envied the older kids who wore Boy Scout uniforms. We shared with the rest of America the same movies, screen heroes and listened to the same heart-rending songs of the forties. We imported much of America into the camps because, after all, we were Americans. Through imitation of my brothers, who attended grade school within the camp, I learned the salute to the flag by the time I was five years old. I was learning, as best one could learn in Manzanar, what it meant to live in America. But, I was also learning the sometimes bitter price one has to pay for it.

After the war, through the Japanese American Evacuation Claims Act, the government attempted to compensate for the losses of real and personal property; inevitably that effort did not secure full or fair compensation. There were many kinds of injury the Evacuation Claims Act made no attempt to compensate: the stigma placed on people who fell under the exclusion and relocation orders; the deprivation of liberty suffered during detention; the psychological impact of exclusion and relocation; the breakdown of family structure; the loss of earnings or profits; physical injury or illness during detention.

The Decision to End Detention

By October 1942, the government held over 100,000 evacuees in relocation camps. After the tide of war turned with the American victory at Midway in June 1942, the possibility of serious Japanese attack was no longer credible; detention and exclusion became increasingly difficult to defend. Nevertheless, other than an ineffective leave program run by the War Relocation Authority, the government had no plans to remedy the situation and no means of distinguishing the loyal from the disloyal. Total control of these civilians in the presumed interest of state security was rapidly becoming the accepted norm.

Determining the basis on which detention would be ended required the government to focus on the justification for controlling the ethnic Japanese. If the government took the position that race determined loyalty or that it was impossible to distinguish the loyal from the disloyal because "Japanese" patterns of thought and behavior were too alien to white Americans, there would be little incentive to end detention. If the government maintained the position that distinguishing the loyal from the disloyal was possible and that exclusion and detention were required only by the necessity of acting quickly under the threat of Japanese attack in early 1942, then a program to release those considered loyal should have been instituted in the spring of 1942 when people were confined in the assembly centers.

Neither position totally prevailed. General DeWitt and the Western Defense Command took the first position and opposed any review that would determine loyalty or threaten continued exclusion from the West Coast. Thus, there was no loyalty review during the assembly center period. Secretary Stimson and Assistant Secretary McCloy took the second view, but did not act on it until the end of 1942 and then only in a limited manner. At the end of 1942, over General DeWitt's opposition, Secretary Stimson, Assistant Secretary McCloy and General George C. Marshall, Chief of Staff, decided to establish a volunteer combat team of Nisei soldiers. The volunteers were to come from those who had passed a loyalty review. To avoid the obvious unfairness of allowing only those joining the military to establish their loyalty and leave the camps, the War Department joined WRA in expanding the loyalty review program to all adult evacuees.

This program was significant, but remained a compromise. It provided an opportunity to demonstrate loyalty to the United States on the battlefields; despite the human sacrifice involved, this was of immense practical importance in obtaining postwar acceptance for the ethnic Japanese. It opened the gates of the camps for some and began some reestablishment of normal life. But, with no apparent rationale or justification, it did not end exclusion of the loyal from the West Coast. The review program did not extend the presumption of loyalty to American citizens of Japanese descent, who were subject to an investigation and review not applied to other ethnic groups.

Equally important, although the loyalty review program was the first major government decision in which the interests of evacuees prevailed, the program was conducted so insensitively, with such lack of understanding of the evacuees circumstances, that it became one of the most divisive and wrenching episodes of the camp detention.

After almost a year of what the evacuees considered utterly unjust treatment at the hands of the government, the loyalty review program began with filling out a questionnaire which posed two questions requiring declarations of complete loyalty to the United States. Thus, the questionnaire demanded a personal expression of position from each evacuee—a choice between faith in one's future in America and outrage at present injustice. Understandably most evacuees probably had deeply ambiguous feelings about a government whose rhetorical values of liberty and equality they wished to believe, but who found their present treatment in painful contradiction to those values. The loyalty questionnaire left little room to express that ambiguity. Indeed, it provided an effective point of protest and organization against the government, from which more and more evacuees felt alienated. The questionnaire finally addressed the central question of loyalty that underlay the exclusion policy, a question which had been the predominant political and personal issue for the ethnic Japanese over the past year; answering it required confronting the conflicting emotions aroused by their relation to the government. Evacuee testimony shows the intensity of conflicting emotions:

I answered both questions number 27 and 28 [the loyalty questions] in the negative, not because of disloyalty but due to the disgusting and shabby treatment given us. A few months after completing the questionnaire, U.S. Army officers appeared at our camp and gave us an interview to confirm our answers to the questions 27 and 28, and followed up with a question that in essence asked: "Are you going to give up or renounce your U.S. citizenship?" to which I promptly replied in the affirmative as a rebellious move. Sometime after the interview, a form letter from the Immigration and Naturalization Service arrived saying if I wanted to renounce my U.S. citizenship, sign the form letter and return. Well, I kept the Immigration and Naturalization Service waiting.

* * *

Well, I am one of those that said "no, no" on it, one of the "no, no" boys, and it is not that I was proud about it, it was just that our legal rights were violated and I wanted to fight back. However, I didn't want to take this sitting down. I was really angry. It just got me so damned mad. Whatever we do, there was no help from outside, and it seems to me that we are a race that doesn't count. So therefore, this was one of the reasons for the "no, no" answer.

Personal responses to the questionnaire inescapably became public acts open to community debate and scrutiny within the closed world of the camps. This made difficult choices excruciating:

After I volunteered for the [military] service, some people that I knew refused to speak to me. Some older people later questioned my father for letting me volunteer, but he told them that I was old enough to make up my own mind.

* * *

The resulting infighting, beatings, and verbal abuses left families torn apart, parents against children, brothers against sisters, relatives against relatives, and friends against friends. So bitter was all this that even to this day, there are many amongst us who do not speak about that period for fear that the same harsh feelings might arise up again to the surface.

The loyalty review program was a point of decision and division for those in the camps. The avowedly loyal were eligible for release; those who were unwilling to profess loyalty or whom the government distrusted were segregated from the main body of evacuees into the Tule Lake camp, which rapidly became a center of disaffection and protest against the government and its policies—the unhappy refuge of evacuees consumed by anger and despair.

The Decision to End Exclusion

The loyalty review should logically have led to the conclusion that no justification existed for excluding loyal American citizens from the West Coast. Secretary Stimson, Assistant Secretary McCloy and General Marshall reached this position in the spring of 1943. Nevertheless, the exclusion was not ended until December 1944. No plausible reason connected to any wartime security has been offered for this eighteen to twenty month delay in allowing the ethnic Japanese to return to their homes, jobs and businesses on the West Coast, despite the fact that the delay meant, as a practical matter, that confinement in the relocation camps continued for the great majority of evacuees for an other year and a half.

Between May 1943 and May 1944, War Department officials did not make public their opinion that exclusion of loyal ethnic Japanese from the West Coast no longer had any military justification. If the President was unaware of this view, the plausible explanation is that Secretary Stimson and Assistant Secretary McCloy were unwilling, or believed themselves unable, to face down political opposition on the West Coast. General DeWitt repeatedly expressed opposition until he left the Western Defense Command in the fall of 1943, as did West Coast anti-Japanese factions and politicians.

In May 1944 Secretary Stimson put before President Roosevelt and the Cabinet his position that the exclusion no longer had a military justification. But the President was unwilling to act to end the exclusion until the first Cabinet meeting following the Presidential election of November 1944. The inescapable conclusion from this factual pattern is that the delay was motivated by political considerations.

By the participants own accounts, there is no rational explanation for maintaining the exclusion of loyal ethnic Japanese from the West Coast for the eighteen months after May 1943—except political pressure and fear. Certainly there was no justification arising out of military necessity.

The Comparisons

To either side of the Commission's account of the exclusion, removal and detention, there is a version argued by various witnesses that makes a radically different analysis of the events. Some contend that, forty years later, we cannot recreate the atmosphere and events of 1942 and that the extreme measures taken then were solely to protect the nation's safety when there was no reasonable alternative. Others see in these events only the animus of racial hatred directed toward people whose skin was not white. Events in Hawaii in World War II and the historical treatment of Germans and German Americans shows that neither analysis is satisfactory.

Hawaii. When Japan attacked Pearl Harbor, nearly 158,000 persons of Japanese ancestry lived in Hawaii—more than 35 percent of the population. Surely, if there were dangers from espionage, sabotage and fifth column activity by American citizens and resident aliens of Japanese ancestry, danger would be greatest in Hawaii, and one would anticipate that the most swift and severe measures would be taken there. But nothing of the sort happened. Less than 2,000 ethnic Japanese in Hawaii were taken into custody during the war—barely one percent of the population of Japanese descent. Many factors contributed to this reaction.

Hawaii was more ethnically mixed and racially tolerant than the West Coast. Race relations in Hawaii before the war were not infected with the same virulent antagonism of 75 years of agitation. While anti-Asian feeling existed in the territory, it did not represent the longtime views of well-organized groups as it did on the West Coast and, without statehood, xenophobia had no effective voice in the Congress.

The larger population of ethnic Japanese in Hawaii was also a factor. It is one thing to vent frustration and historical prejudice on a scant two percent of the population; it is very different to disrupt a local economy and tear a social fabric by locking up more than one-third of a territory's people. And in Hawaii the half-measure of exclusion from military areas would have been meaningless.

In large social terms, the Army had much greater control of day-to-day events in Hawaii. Martial law was declared in December 1941, suspending the writ of habeas corpus, so that through the critical first months of the war, the military's recognized power to deal with any emergency was far greater than on the West Coast.

Individuals were also significant in the Hawaiian equation. The War Department gave great discretion to the commanding general of each defense area and this brought to bear very different attitudes toward persons of Japanese ancestry in Hawaii and on the West Coast. The commanding general in Hawaii, Delos Emmons, restrained plans to take radical measures, raising practical problems of labor shortages and transportation until the pressure to evacuate the Hawaiian Islands subsided. General Emmons does not appear to have been a man of dogmatic racial views; he appears to have argued quietly but consistently for treating the ethnic Japanese as loyal to the United States, absent evidence to the contrary.

This policy was clearly much more congruent with basic American law and values. It was also a much sounder policy in practice. The remarkably high rate of enlistment in the Army in Hawaii is in sharp contrast to the doubt and alienation that marred the recruitment of Army volunteers in the relocation camps. The wartime experience in Hawaii left behind neither the extensive economic losses and injury suffered on the mainland nor the psychological burden of the direct experience of unjust exclusion and detention.

The German Americans. The German American experience in the First World War was far less traumatic and damaging than that of the ethnic Japanese in the Second World War, but it underscores the power of war fears and war hysteria to produce irrational but emotionally powerful reactions to people whose ethnicity links them to the enemy.

There were obvious differences between the position of people of German descent in the United States in 1917 and the ethnic Japanese at the start of the Second World War. In 1917, more than 8,000,000 people in the United States had been born in Germany or had one or both parents born there. Although German Americans were not massively represented politically, their numbers gave them notable political strength and support from political spokesmen outside the ethnic group.

The history of the First World War bears a suggestive resemblance to the events of 1942: rumors in the press of sabotage and espionage, use of a stereotype of the German as an unassimilable and rapacious Hun, followed by an effort to suppress those institutions—the language, the press and the churches—that were most palpably foreign and perceived as the seedbed of Kaiserism. There were numerous examples of official and quasi-governmental harassment and fruitless investigation of German Americans and resident German aliens. This history is made even more disturbing by the absence of an extensive history of anti-German agitation before the war.

* * *

The promulgation of Executive Order 9066 was not justified by military necessity, and the decisions which followed from it—detention, ending detention and ending exclusion—were not driven by analysis of military conditions. The broad historical causes which shaped these decisions were race prejudice, war hysteria and a failure of political leadership. Widespread ignorance of Japanese Americans contributed to a policy conceived in haste and executed in an atmosphere of fear and anger at Japan. A grave injustice was done to American citizens and resident aliens of Japanese ancestry who, without individual review or any probative evidence against them, were excluded, removed and detained by the United States during World War II.

In memoirs and other statements after the war, many of those involved in the exclusion, removal and detention passed judgment on those events. While believing in the context of the time that evacuation was a legitimate exercise of the war powers, Henry L. Stimson recognized that "to loyal citizens this forced evacuation was a personal injustice." In his autobiography, Francis Biddle reiterated his beliefs at the time: "the program was ill-advised, unnecessary and unnecessarily cruel." Justice William O. Douglas, who joined the majority opinion in Korematsu which held the evacuation constitutionally permissible, found that the evacuation case was ever on my conscience. Milton Eisenhower described the evacuation to the relocation camps as "an inhuman mistake." Chief Justice Earl Warren, who had urged evacuation as Attorney General of California, stated, "I have since deeply regretted the removal order and my own testimony advocating it, because it was not in keeping with our American concept of freedom and the rights of citizens." Justice Tom C. Clark, who had been liaison between the Justice Department and the Western Defense Command, concluded, "Looking back on it today [the evacuation] was, of course, a mistake."

PART II: THE ALEUTS

During the struggle for naval supremacy in the Pacific in World War II, the Aleutian Islands were strategically valuable to both the United States and Japan. Beginning in March 1942, United States military intelligence repeatedly warned Alaska defense commanders that Japanese aggression into the Aleutian Islands was imminent. In June 1942, the Japanese attacked and held the two westernmost Aleutians, Kiska and Attu. These islands remained in Japanese hands until July and August 1943. During the Japanese offensive in June 1942, American military commanders in Alaska ordered the evacuation of the Aleuts from many islands to places of relative safety. The government placed the evacuees in camps in southeast Alaska where they remained in deplorable conditions until being allowed to return to their islands in 1944 and 1945.

The Evacuation

The military had anticipated a possible Japanese attack for some time before June 1942. The question of what should be done to provide security for the Aleuts lay primarily with the civilians who reported to the Secretary of the Interior: the Office of Indian Affairs, the Fish and Wildlife Service and the territorial governor. They were unable to agree upon a course of action—evacuation and relocation to avoid the risks of war, or leaving the Aleuts on their islands on the ground that subsistence on the islands would disrupt Aleut life less than relocation. The civilian authorities were engaged in consulting with the military and the Aleuts when the Japanese attacked.

At this point the military hurriedly stepped in and commenced evacuation in the midst of a rapidly developing military situation. On June 3, 1942, the Japanese bombed the strategic American base at Dutch Harbor in the Aleutians; as part of the response a U.S. ship evacuated most of the island of Atka, burning the Aleut village to prevent its use by Japanese troops, and Navy planes picked up the rest of the islanders a few days later.

In anticipation of a possible attack, the Pribilof Islands were also evacuated by the Navy in early June. In early July, the Aleut villages of Nikolski on Umnak Island, and Makushin, Biorka, Chernofski, Kashega and Unalaska on Unalaska Island, and Akutan on Akutan Island were evacuated in a sweep eastward from Atka to Akutan.

At that point, the Navy decided that no further evacuation of Aleut villages east of Akutan Island was needed. Eight hundred seventy-six Aleuts had been evacuated from Aleut villages west of Unimak Island, including the Pribilofs. Except in Unalaska the entire population of each village was evacuated, including at least 30 non-Aleuts. All of the Aleuts were relocated to southeastern Alaska except 50 persons who were either evacuated to the Seattle area or hospitalized in the Indian Hospital at Tacoma, Washington.

The evacuation of the Aleuts had a rational basis as a precaution to ensure their safety. The Aleuts were evacuated from an active theatre of war; indeed, 42 were taken prisoner on Attu by the Japanese. It was clearly the military's belief that evacuation of non-military personnel was advisable. The families of military personnel were evacuated first, and when Aleut communities were evacuated the white teachers and government employees on the islands were evacuated with them. Exceptions to total evacuation appear to have been made only for people directly employed in war-related work.

The Aleuts' Camps

Aleuts were subjected to deplorable conditions following the evacuation. Typical housing was an abandoned gold mine or fish cannery buildings which were inadequate in both accommodation and sanitation. Lack of medical care contributed to extensive disease and death.

Conditions at the Funter Bay cannery in southeastern Alaska, where 300 Aleuts were placed, provide a graphic impression of one of the worst camps. Many buildings had not been occupied for a dozen years and were used only for storage. They were inadequate, particularly for winter use. The majority of evacuees were forced to live in two dormitory-style buildings in groups of six to thirteen people in areas nine to ten feet square. Until fall, many Aleuts were forced to sleep in relays because of lack of space. The quarters were as rundown as they were cramped. As one contemporary account reported:

The only buildings that are capable of fixing is the two large places where the natives are sleeping. All other houses are absolutely gone from rot. It will be almost impossible to put toilet and bath into any of them except this one we are using as a mess hall and it leaks in thirty places. . . . No brooms, soap or mops or brushes to keep the place suitable for pigs to stay in.

People fell through rotten wooden floors. One toilet on the beach just above the low water mark served ninety percent of the evacuees. Clothes were laundered on the ground or sidewalks.

Health conditions at Funter Bay were described in 1943 by a doctor from the Territorial Department of Health who inspected the camp:

As we entered the first bunkhouse the odor of human excreta and waste was so pungent that I could hardly make the grade. . . . The buildings were in total darkness except for a few candles here and there [which] I considered distinct fire hazards. . . . [A] mother and as many as three or four children were found in several beds and two or three children in one bunk. . . . The garbage cans were overflowing, human excreta was found next to the doors of the cabins and the drainage boxes into which dishwater and kitchen waste was to be placed were filthy beyond description. . . . I realize that during the first two days we saw the community at its worst. I know that there were very few adults who were well. . . . The water supply is discolored, contaminated and unattractive. . . . [F]acilities for boiling and cooling the water are not readily available. . . . I noticed some lack of the teaching of basic public health fundamentals. Work with such a small group of people who had been wards of the government for a long period of time should have brought better results. It is strange that they could have reverted from a state of thrift and cleanliness on the Islands to the present state of filth, despair, and complete lack of civic pride. I realize, too, that at the time I saw them the community was largely made up of women and children whose husbands were not with them. With proper facilities for leadership, guidance and stimulation . . . the situation could have been quite different.

In the fall of 1942, the only fulltime medical care at Funter Bay was provided by two nurses who served both the cannery camp and a camp at a mine across Funter Bay. Doctors were only temporarily assigned to the camp, often remaining for only a few days or weeks. The infirmary at the mining camp was a three-room bungalow; at the cannery, it was a room twenty feet square. Medical supplies were scarce.

Epidemics raged throughout the Aleuts' stay in southeastern Alaska; they suffered from influenza, measles, and pneumonia along with tuberculosis. Twenty-five died at Funter Bay in 1943 alone, and it is estimated that probably ten percent of the evacuated Aleuts died during their two or three year stay in southeastern Alaska.

To these inadequate conditions was added the isolation of the camp sites, where climatic and geographic conditions were very unlike the Aleutians. No employment meant debilitating idleness. It was prompted in part by government efforts to keep the Pribilovians, at least, together so that they might be returned to harvest the fur seals, an enterprise economically valuable to the government. Indeed a group of Pribilovians were taken back to their islands in the middle of the evacuation period for the purpose of seal harvesting.

The standard of care which the government owes to those within its care was clearly violated by this treatment, which brought great suffering and loss of life to the Aleuts.

Return to the Islands

The Aleuts were only slowly returned to their islands. The Pribilovians were able to get back to the Pribilofs by the late spring of 1944, nine months after the Japanese had been driven out of the Aleutian chain. The return to the Aleutians themselves did not take place for another year. Some of this delay may be fairly attributed to transport shortage and problems of supplying the islands with housing and food so that normal life could resume. But the government's record, especially in the Aleutians, reflects an indifference and lack of urgency that lengthened the long delay in taking the Aleuts home. Some Aleuts were not permitted to return to their homes; to this day, Attuans continue to be excluded from their ancestral lands.

The Aleuts returned to communities which had been vandalized and looted by the military forces. Rehabilitation assessments were made for each village; the reports on Unalaska are typical:

All buildings were damaged due to lack of normal care and upkeep. . . . The furnishings, clothing and personal effects, remaining in the homes showed, with few exceptions, evidence of weather damage and damage by rats. Inspection of contents revealed extensive evidence of widespread wanton destruction of property and vandalism. Contents of closed packing boxes, trunks and cupboards had been ransacked. Clothing had been scattered over floors, trampled and fouled. Dishes, furniture, stoves, radios, phonographs, books, and other items had been broken or damaged. Many items listed on inventories furnished by the occupants of the houses were entirely missing. . . . It appears that armed forces personnel and civilians alike have been responsible for this vandalism and that it occurred over a period of many months.

Perhaps the greatest loss to personal property occurred at the time the Army conducted its clean up of the village in June of 1943. Large numbers of soldiers were in the area at that time removing rubbish and outbuildings and many houses were entered unofficially and souvenirs and other articles were taken.

When they first returned to the islands, many Aleuts were forced to camp because their former homes (those that still stood) had not yet been repaired and many were now uninhabitable. The Aleuts rebuilt their homes themselves. They were "paid" with free groceries until their homes were repaired; food, building and repair supplies were procured locally, mostly from military surplus.

The Aleuts suffered material losses from the government's occupation of the islands for which they were never fully recompensed, in cash or in kind. Devout followers of the Russian Orthodox faith, Aleuts treasured the religious icons from czarist Russia and other family heirlooms that were their most significant spiritual as well as material losses. They cannot be replaced. In addition, possessions such as houses, furniture, boats, and fishing gear were either never replaced or replaced by markedly inferior goods.

In sum, despite the fact that the Aleutians were a theatre of war from which evacuation was a sound policy, there was no justification for the manner in which the Aleuts were treated in the camps in southeastern Alaska, nor for failing to compensate them fully for their material losses.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

personal-justice-denied/summary.htm

Last Updated: 08-Jan-2007