|

Fort Clatsop

Administrative History |

|

CHAPTER TWO:

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

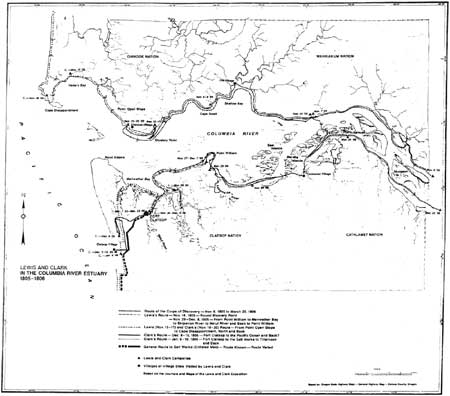

The area around the mouth of the Columbia River, where the Corps of Discovery spent the winter of 1805-1806, was home to the Lower Chinookan peoples. More specifically, the site of their fort was in the territory of the Clatsops, after whom they named their fort. The Clatsops were already very familiar with European maritime traders and explorers traveling along the Pacific Coast. European contact (disease and the influx of European goods such as guns) affected them long before the Lewis and Clark Expedition arrived. But no group from any European nation had ever spent as much time interacting with and recording information about the Chinookan people as did the Expedition. The material recorded by the Lewis and Clark Expedition during their stay is the best contact-era observation of the Chinookan people and their life prior to the settlement of the Oregon Country and the end of their precontact way of life.

The Lower Chinook

The name Chinookan applies to the linguistic group made up of the different tribes or villages from the mouth of the Columbia up river to The Dalles. Within this group, the Chinookan are divided into the Lower and Upper Chinookan, each containing different villages and some dialect variations. The name Chinook was derived by European and American traders from the Salish name for a specific village on Baker Bay. As European and American traders moved through the area, all the villages on the north side of the Columbia that shared the same language, from Grays Bay, about 15 miles inland, to north end of Willapa Bay, became known as the Chinook proper. [1] The Clatsops, who probably shared the same Chinookan dialect as the Chinook proper, lived on the south side of the Columbia, from Cape Adams to Tongue Point and south along the coast to Tillamook Head. The Chinook proper and the Clatsops are the two primary members of the Lower Chinookan peoples.

The Lower Chinookan were fishers, gatherers, hunters, and traders. Their diet included salmon and other fish, various berries and roots including the wapato root and the salal berry, elk, deer, waterfowl, small mammals like beaver and rabbits, and occasional whales and sea lions. [2] Fishing was done with seine nets, spears, rakes, and hooks. Hunting methods included traps, snares, spears, bows and arrows, and with the arrival of European trade ships off the Pacific Coast during the 1700's, muskets. Hunting and gathering also supplied materials for clothing and essential Chinookan household items, such as baskets, hats, mats, and utensils carved from bone and wood. Clothing was fairly sparse, generally consisting of grass skirts or mats and robes made from animal skins and furs.

The Lower Chinookans lived in villages of semi-permanent houses, moving to established fishing camps during the peak fish runs. They lived in oblong houses built from cedar log frames with cedar planking for walls and roofs. Although the number of houses per village varied, each house usually home to a patrilocal extended family of around 20 individuals. The village was the primary social unit and was linked to other villages by ties of trade and kinship. The Lower Chinookan were expert canoe builders, carving as many as six different functional styles from cedar logs. [3] The canoe was their main mode of transportation and, owing to their strong reliance on the ocean and river for their subsistence, were highly valued pieces of property. Lewis and Clark, who had hoped to procure a canoe from their neighbors, fretted on many occasions about the high prices the Clatsops asked for their canoes.

Within Chinookan society, there was division by class and rank, as well as by free and slave status. Usually obtained through trade, slave status was hereditary. Each village had a headman or chief and leadership rights were hereditary. Chiefs generally had control of only their own village, although an influential chief could gain influence over other villages. Status and influence were maintained by wealth and free Chinookans could elevate or lower their status in society through its accumulation or loss. The most famous trait of Chinookan culture was the practice of flattening a person's forehead during infancy. This was done by placing a baby or developing child into a cradle and strapping a board to the cradle and child, which applied pressure to the front of the forming skull. Slaves were not allowed this feature. Marriage was polygynous and marriage alliances were used to obtain both status and commercial ties to other villages. At death, the Chinooks placed a person's remains in an elevated canoe, the Clatsops in an elevated carved box and an individual's rank or class defined how elaborate the "burial." Slaves were not given a ceremonial burial.

The Pacific Northwest Indian groups were members of a highly developed, geographically extensive trade system and the Lower Chinookans were an integral part of that system. Dentalium shells from Vancouver Island were a primary currency item among the Chinook and their trade partners. [4] Trips up the Columbia to trade markets were common. By the time European and American traders arrived, including Lewis and Clark, this trade system was well entrenched and the different Indian groups tried to incorporate these new trade partners into the existing system.

The Corps of Discovery

When the Corps of Discovery arrived at the Pacific, the expedition consisted of thirty-three people and one dog. Of the thirty-three, most were American frontiersmen or furtraders. A few were French-Canadian or other European descent. Toussaint Charbonneau and his American Indian wife, Sacagawea, were hired as interpreters for the expedition and were accompanied by their infant child. William Clark's African-American slave York was also a member of the expedition.

After reaching the Pacific Ocean, the Corps voted to move up the Netul River (the present day Lewis and Clark River) to a camp site selected by Captain Lewis in early December, 1805. Work clearing the site for a fort began immediately. By December 10, the foundations for their rooms were laid and by December 14, they had finished the room walls and had begun roofing the meat house room. All roofing was completed by December 24 and the walls were daubed with mud. The captains moved into their room on December 23, the rest of the expedition moving in on Christmas Eve and Day. The rooms had bunks and puncheon5 ] floors. After Christmas, they installed interior chimneys in the living quarters and installed pickets and gates. On December 31, they built a sentinel box and dug two "sinks."6]

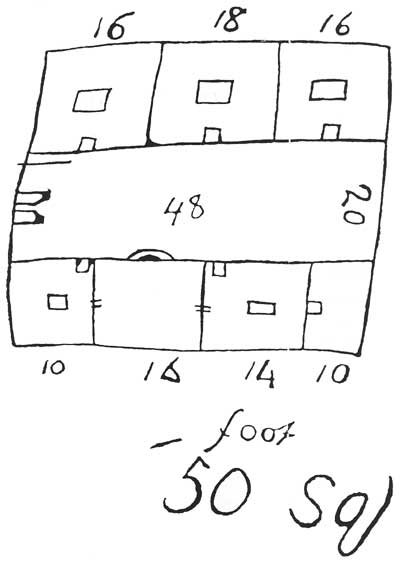

The journals do not give a detailed description of the fort. Expedition journals offer two floor plans, one drawn by Sergeant John Ordway and one by Captain William Clark. The two floor plans differ. Precedence has traditionally been given to Clark's documentation due to his rank and role in directing construction. By Clark's description, the fort was fifty feet square with two parallel cabins. One cabin contained 3 rooms, each with a central firepit, which were the enlisted men's quarters. The opposite cabin contained four rooms, two with firepits and one with a fireplace and exterior chimney. The orderly room, which had a firepit; the store room, which had a locking door; the room shared by the captains, which had a fireplace and exterior chimney; and the Charbonneau family room were all located on this side. Two gates were installed, one at each end of the parade ground. One was the main gate, which was locked at night. At the opposite end, the second gate was used to access the spring for water or other necessary trips outside the fort.

The expedition party stayed at Fort Clatsop until March 23, 1806, when they set out on their return journey. During their stay, hunting was a major occupation for the Expedition members, and hunting parties were often away from the fort overnight or even for a few days. It was a continual process providing food for so many people. The party lived primarily off elk, consuming also deer and fish, wapato roots, some water fowl and beaver, dog, and the rare treat of whale blubber. Well before they had selected the site of Fort Clatsop and built their quarters, the damp climate had rotted their clothing, tents, and other hide based goods. The animal hides brought in from hunting were used to make new clothing, moccasins, bags, and covers for their luggage. Members also spent time preparing game meat, rendering candles, and repairing weapons. A group from the expedition party was sent to the coast to extract salt from sea water, leaving Fort Clatsop on December 28, 1805. They established a camp site near a Clatsop village at present day Seaside and made salt continuously until their return to Fort Clatsop on February 21, 1806.

A system of guard duty was established which constantly occupied a sergeant and three enlisted men. The guard was in charge of announcing approaching groups of Indians, opening and closing the gates, tending the meat house fires and wood supply, periodically checking the condition of the canoes at the landing site, and bringing in wood for the fireplace in the captains' quarters.

Chinook and Clatsops interacted extensively with the Expedition, exchanging goods, services, and information on a regular basis. The captains occupied their time preparing their journals and maps. Lewis' journal from Fort Clatsop ended a three month hiatus from journal keeping and provides some of his best ethnographic and botanical information recorded during the expedition. Both captains made separate trips out to the coast, one of these being a trip led by Captain Clark to procure some blubber and oil from a beached whale.

Generally speaking, the expedition party was miserable while at Fort Clatsop. Fleas tormented them and it rained on all but twelve days of their stay. The weather was usually grey and wet, which made them disagreeable. Illness and injuries abounded during their stay, ranging from colds, fevers, and muscle strains, which the men contracted while tracking, hunting, and carrying game long distances in rough, damp terrain often miles away from the fort, to venereal disease. Their diet was usually less than desirable owing to the dampness which quickly spoiled their meat. Their general discomfort and the movement of elk herds to the mountains persuaded the expedition to leave on March 23, 1806, rather than the April 1 departure date established earlier.

|

| (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

Settlement of the Site, 1806-1899

On March 22, 1806, Lewis recorded in his journal the visit of Chief Comowool and three Clatsops. He states "to this Chief we left our houses and furniture." [7 ] According to descendants of Comowool, he used the fort during hunting season for several years after the Expedition left. [8] Beginning in 1811 with the arrival of John Jacob Astor's Pacific Fur Company and the establishment of the fur post at Fort Astoria, there is a record of visitation to the site by American and European traders, explorers, and settlers. On October 2, 1811, Gabriel Franchere, a member of the Pacific Fur Company, reported visiting the ruins of the fort and seeing only a pile of rough unhewn logs. A second trip was made by Ross Cox in May or June 1812. He noted that logs from the fort were still standing and marked with the names of several of the party.

In 1813, after the outbreak of the War of 1812 and the loss of their annual trade ship, the Pacific Fur Company sold out to the North West Company. Fort Astoria was taken over by the British and renamed Fort George. [9] In 1813, Alexander Henry of the North West Company and a captain of the British Royal Navy made a canoe trip to the site. At that time they found two Clatsop houses at the site, saw the remains of the fort and reported willows growing up inside the remains. They reported that the Clatsops had cut down and used a good portion of the wood from the fort walls. An 1821 Congressional report on settlement of the Oregon Country stated the fort remains could still be seen. [10] Various other travelers and settlers took the time to visit the site and their documentation gives a record of the site's condition over time. [11]

In 1849, S.M. Henell of Astoria attempted to claim land containing the site of Fort Clatsop through a donation under an Oregon Provisional Government land claim law. The next year, however, Thomas Scott jumped Henell's claim under the federal 1850 Donation Act and shortly thereafter traded the property to Carlos Shane. Shane built a house a few feet from the remains of the fort. In 1852 or 1853, Carlos Shane's brother, Franklin Shane, moved to the site. Carlos Shane moved up river and transferred the site to Franklin. The claim consisted of approximately 320 acres along the west bank of the Lewis and Clark River, and included the fort site and the site along the river bank believed to be the Corps' canoe landing. In 1852, Richard Moore wanted to build a mill at the canoe landing site. An agreement was reached between Shane and Moore resulting in the movement of Shane's boundary slightly north so that Moore could claim the landing. [12] Moore built a mill and from 1852 to 1854 the area around the mill was logged and lumber sent by boat from the canoe landing site to San Francisco. [13]

During this time, Franklin Shane put in an orchard on his property. In 1853, Fort Clatsop was its own voting precinct with 56 votes polled. [14 ] In 1854, the bottom fell out of the lumber market and the mill closed. Three years later, when Franklin Shane refiled papers for his claim, the boundary returned to its original place and included the landing in his property. [15] Donation Certificate number 5001 was issued to Franklin Shane in 1857. The claim was 320.5 acres, stretching about half a mile along the west bank of the river and extending about a mile inland.

Franklin Shane died between 1860 and 1867 and his property was inherited by his two daughters. In 1872, the husband of Mary Shane, William (Wade) Hampton Smith, was given title to the half of the Shane claim that contained the Fort Clatsop site. Smith built a new house on the property, the house Carlos Shane built reportedly having burned down. William Smith, Mary, and their children lived at the site for eight years until they moved to Portland in 1880.

One of William Smith's sons, Harlan C. Smith, returned to the Fort Clatsop site during the summer of 1957. [16] On July 6, 1957, National Park Service officials conducted an interview with Smith about his childhood at the site. Harlan was 2 years old in 1872 when his family moved to the site and his father built their house. While living at Fort Clatsop, Harlan remembered his father worked as the postmaster for the Fort Clatsop post office, distributing mail out of their home. He also operated a brick manufacturing business for awhile. According to Smith, his father built the road from Fort Clatsop to the Clatsop Plains under contract with the Oregon Steam and Navigation Company.

Harlan Smith was able to share his memories of the site as well as his mother's, who had spent a good deal of her childhood there. She remembered seeing the ruins of Fort Clatsop and recounted to Harlan where they were. She also told Harlan that a decaying, half buried log, running east-west along the north edge of their house, was the last remaining timber of the fort ruins. [17]

When the Smiths moved to Portland in 1880, the Joseph B. Stevenson family, who had been the Smiths' neighbors, rented the house and property from William Smith. Over several years, one of Stevenson's occupations at the site was making and selling charcoal. He was also engaged with the Oregon Steam and Navigation Company operations at the canoe landing site.

The canoe landing site continued to be used in other ventures. During the summers of 1860-1862, the United States Revenue Service docked their cutter for maintenance at the landing. [18] The landing site had also become part of the main route used by tourists traveling to the coast. Travelers would take ships from Portland or Astoria to Fort Clatsop and then take a carriage or horse to Seaside. In 1862, the Oregon Steam and Navigation Company established a regular summer service from Portland to Fort Clatsop and in 1875, William Smith sold 5 acres along the river to the company. [19] While the Stevensons were tenants at Fort Clatsop, they ran a carriage service from the landing to Seaside. By 1900, however, new transportation routes to meet the needs of the increasing numbers of tourists eliminated the Fort Clatsop route. The Oregon Steam Navigation Company had become the Oregon Railroad and Navigation Company, and continued to own the five-acre parcel along the river.

Another economic development at the Fort Clatsop site was the discovery of clay deposits. William Smith extracted clay from three locations near the fort site. [20] In 1887, Mary Shane Smith sold half of the clay and mineral rights on the Shane claim to the Oregon Pottery Company. [21] Clay and mineral rights at the site were bought and sold several times during the next thirty years. From 1887 until probably 1920, clay was apparently extracted from an area just southwest of the three acres obtained as the fort site in 1900 by the Oregon Historical Society. [22]

During the period from 1806 to 1899, the site of Fort Clatsop was generally known to the local population. The Clatsops certainly remembered the site and from 1811 until 1850, remains of a log structure at the present site were considered to be the remains of Fort Clatsop and pointed out as such to visitors and new settlers. After natural deterioration, the affects of agricultural production, home building, and other pursuits had obliterated those log remains, the site remained known as Fort Clatsop to the local population through oral tradition. Those settlers who had seen the remains pointed out the location to their children.

Identification of the Site, 1899-1900

By 1899, public interest in establishing the specific location of the fort grew. During that year, a writer for the Northern Pacific Railway named Olin D. Wheeler arrived on the scene. He was attempting to trace the route of the Lewis and Clark Expedition and this inevitably brought him to Astoria in search of Fort Clatsop. Wheeler got a group of local people who knew the site to take him there around August 28-29, 1899. In his party were four long-time Astorians and the grandson of Chief Comowool, Silas B. Smith, as well as a representative of the Oregon Historical Society and a photographer. The five men were in general agreement as to the location of the site, which they pointed out to Wheeler, and a series of photographs were taken. However, Wheeler did not record the exact location of the identified site, leaving only photographic evidence as their identification.

|

|

Identification of Fort Clatsop, 30

August 1899. Shown in photo are: O.D. Wheeler, Silas Smith, William

Chance, George W. Lownsburg, George Noland, George H. Hines (OHS

representative), the caption of the boat launch, and J.Q.A. Bowlley. (Photo courtesy of Oregon Historical Society, photo negative number 1694) |

Due to Wheeler's lack of documentation, the process of identification was repeated in June 1900, when the Oregon Historical Society decided to locate the site in hopes of placing a marker on it. This time, the identification party consisted of Silas B. Smith, Carlos Shane, Preston W. Gillette, and two members of the historical society. Carlos Shane was the first resident settler of the site. Preston W. Gillette settled a land claim a couple of miles away. No surveyor accompanied them. The party pointed out where they remembered seeing the southwest corner of the fort and placed a stake in the ground. Using that corner as a base, they then placed three more stakes where they speculated the other three corners of the stockade would have been. The historical society then took depositions from the settlers, who described when they saw the fort remains, what they saw, and where they saw them. An important factor in identifying the Fort Clatsop site comes from Shane's testimony and his recollection about the fort remains' size and layout. Shane stated that there were two cabins parallel to each other, about 15 feet apart, each cabin being about 16 by 30 feet. [23] What is significant about this description is that it roughly follows William Clark's floor plan of Fort Clatsop drawn on the elk-hide cover of his journal. However, Clark's floor plan was not made public until 1904. The correspondence of Shane's observations with Clark's floor plan is perhaps the strongest evidence to substantiate that the site pointed out was indeed the site of Fort Clatsop. Also in these depositions, Carlos Shane admitted to trying to burn the remains after building his house so he could use the land. Gillette reported first seeing the ruins in 1853 and that the log ends were burned, so Shane was not entirely successful. The fact that Shane tried is a testimony to the fact that while the site was important enough to be sought out and visited by passersby and other locals, it was not important enough to those using the land to try and preserve the historic remains in any way. The testimony of Shane, Gillette, and Smith convinced the historical society that the location of Fort Clatsop was permanently fixed and in 1901 the society purchased a three-acre site that contained the fort site.

|

|

Identification of Fort Clatsop, 30

August 1899. Shown are George Noland, Silas Smith (pointing), George

Hines. (Photo courtesy of Oregon Historical Society, photo negative number 1692-93) |

Oregon Historical Society Management and the Sesquicentennial

It was not until 1912 that the historical society was able to install a bronze marker at the site. By then, the stakes that had been placed in 1900 could not be found and since the placement of the first stake was not recorded by a surveyor, it is not clear how they determined where to place the marker. [24]

|

| OHS flagpole and commemorative marker, Woodfield Photo Studio. (Photo courtesy of Oregon Historical Society, photo negative number 90816) |

In 1928, the society was able to purchase two additional acres to the south adjoining their existing acreage and containing a freshwater spring thought to be used by the expedition party during that winter. [25] The site was also cleared, a flagpole erected, and the bronze tablet placed on the cement base of the flagpole. Clatsop County improved the county road leading to the site at that time as well. Over the years, the bronze marker was stolen and replaced at least twice and was removed again during World War II. The site was available to public visitation and occasional cleanup projects were conducted by local civic groups.

By the late 1940s, speculation about the authenticity of the site was great enough that Lancaster Pollard, who was director of the Oregon Historical Society at the time, contacted the National Park Service and asked for assistance in completing an archeological survey at the site. The park service sent Region Four archeologist Louis Caywood to assist the historical society. Caywood conducted excavations at the site during July 9-17, 1948. Caywood reported that his excavations were done on the site of the Lewis and Clark encampment. Caywood's excavations will be discussed in greater detail in a later chapter. Aside from brief consideration in 1948 that a Hollywood studio might build a replica of the fort for a movie, nothing changed at the site after the excavations, and there was no regular maintenance program.

|

| William Clark's sketch of Fort Clatsop, drawn on the elkskin cover of his journal. |

In 1953, an editorial in the Oregonian expressed distress at the deplorable condition of the Fort Clatsop site. The site had become a dumping ground, strewn with litter. The Clatsop County Historical Society had been sponsoring cleanup projects at the site since 1947, but those projects were the only maintenance provided. The 1953 editorial happened to correspond with the establishment of the Astoria Junior Chamber of Commerce, or Jaycees, who were looking for a civic project to which they could devote their energy. Cleaning up the Fort Clatsop site seemed like the perfect project. During the summer of 1953, the Jaycees improved the site, removing trash, mowing the brush and grass around the marker area, and restoring the bronze marker that had been in storage since World War II.

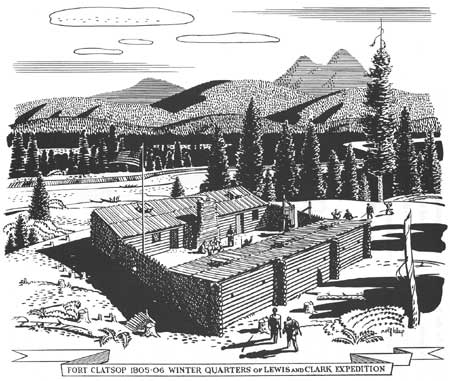

During 1954, planning for Lewis and Clark Sesquicentennial celebrations began. The local community decided early that the center of their celebrations would be the Fort Clatsop site. The idea for a reconstruction of Fort Clatsop had been considered before, appearing in print in 1948 when Lancaster Pollard of the Oregon Historical Society told the press that a Hollywood movie company was considering building one. The idea also arose in a letter from a Portland doctor supporting national recognition for the site in 1953. While plans for the Sesquicentennial were getting under way, the Jaycees and the Clatsop County Historical Society decided they should build a replica of Fort Clatsop and formed a joint committee to finance its construction. Wilt Paulson, then president of the Jaycees, named Wesley Shaner, Jr. the project manager, and the Clatsop County Historical Society assigned their secretary, Burnby Bell, to the project. These two were the primary coordinators for the replica project. [26]

Throughout 1954 until August 21, 1955, when the replica was finished and dedicated, many local groups and individuals donated time, effort, and money. First, the project managers contacted Astorian RoIf Klep, an artist who was living in New York City. They asked Klep to research the expedition journals and provide a drawing of the fort. They also approached the Oregon Historical Society (OHS) for permission to construct the replica, which was granted by the society's president, Burt Brown Barker. Barker served on the Oregon governor-appointed committee for the Sesquicentennial celebration and made a personal donation of $100 for work at the site. However, minutes from Clatsop County Historical Society meetings indicate that not all members of the Oregon Historical Society supported the project, undoubtedly because the replica would ultimately fall to them to manage. [27]

After receiving approval from OHS, Wes Shaner and Wilt Paulson approached the vice president of Crown Zellerbach, Ed Stamm, about the possible donation of logs for the fort project. Stamm agreed to donate the logs and further volunteered to "wolmanize" the logs (injecting chemical preservatives into the wood) at no cost. Paulson remembers Stamm saying that if they were going to build the thing, they needed to make it last at least fifty years. [28] In all, Crown Zellerbach provided 408 logs, each approximately 40 feet long with a minimum diameter of 7 inches and an 11 inch base. The logs came from the area around Vernonia, Oregon, and were removed from the forest by draft horses to prevent scarring by logging machinery. Crown Zellerbach provided transportation of the logs and wolmanization at their plant in Wauna, Oregon.

Next, the project managers approached the Finnish Brotherhood of Astoria for help with carpentry skills. The Jaycees had plenty of labor to donate, but no one with fort building experience. Through the Finnish Brotherhood, they received not only technical advice and more volunteers, but also the only hired help on the project, Olavi Hietaharju. Hietaharju was from Finland and had previous cabin-building experience. He was hired by the Oregon Historical Society as foreman for the replica project.

|

| Rolf Klep's rendition of Fort Clatsop, utilized in the construction of the Fort Clatsop Replica. |

Rolf Klep completed a charcoal sketch of Fort Clatsop and sent it back to the project coordinators. The sketch was based on William Clark's fifty-foot-square floor plan and what little description was given in the journals. Due to the lack of documentation on the Fort Clatsop structure, Klep turned to the Expedition's previous fort-building experience for possible clues to their construction habits. The Expedition had constructed Fort Mandan, also named for the local Indian people, in which to spend the winter of 1804-1805. The inward sloping roofs of the Fort Clatsop replica are derived from the Fort Mandan structure. Fort Mandan was built in a triangle with the roofs slanted toward an inner court. Klep possibly also relied on examples of log cabins of the 1800s to help him formulate what the fort looked like, but some speculation had to have been involved. For example, Klep's drawing has gun ports at the fort when no mention is made of them existing and it is unlikely that they did. When Klep's drawing was made available, John Wicks, a local architect, made working construction plans from the sketch. Hietaharju followed these plans in the fort construction. The Jaycees also asked Klep for permission to sell copies of his sketch to raise money for the replica project, which he granted. The Jaycees sold prints of the sketch for $10 a piece.

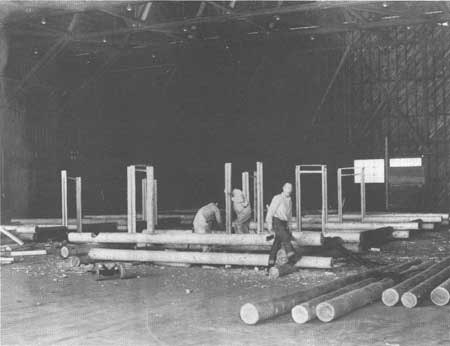

At the time of the replica-building project, Wilt Paulson was manager of the Astoria airport where he arranged for space in the airport hanger for pre-fabrication of the fort building. The plan was to build the fort in the hanger, mark and number the logs, then send them out to be wolmanized. When the logs returned, they would reassemble the fort at the actual site. Through the end of 1954 and into 1955, the volunteers worked on the pre-fabrication work. Hietaharju was there to direct the volunteers in the construction. The fort replica was completed early in 1955, then disassembled and the logs sent out for wolmanizing. In early August 1955, the logs returned from Wauna. To the Jaycees dismay, the banding of the logs for reassembly was destroyed during the wolmanizing process. They returned the logs to the airport hanger, reassembled and remarked the logs, disassembled the fort, and then moved the logs to the site. By the time the replica was finished, they had put it together three times.

The Astoria Lions Club donated materials and labor for building a cement foundation for the fort. Early in August, foundation lines were staked out and the foundation built. How they decided where to place the replica is somewhat sketchy. It is known that they used the spring as a reference point with distances given in the journals, assuming that the spring is the one mentioned. [29] They also had to place the fort in relation to the county road, which at the time came right up to the marker site. A letter from Thomas Vaughan years later states that OHS directed the Jaycees to place the replica directly next to the fort site. This likely meant next to the bronze marker and flagpole, assuming that those markers were on the exact site. The Jaycees considered the weather in deciding which direction the fort's main gate would face using the theory that if the main gate faced the river, wind and rain would blow right into the fort grounds.

While digging the replica's foundation trenches, it is reported the volunteers did find charcoal remnants or pits. Nothing seems to have been done with any of these materials. National Park Service regional historian John Hussey speculated in a 1957 report that they may have found remnants of Joseph B. Stevenson's charcoal operations.

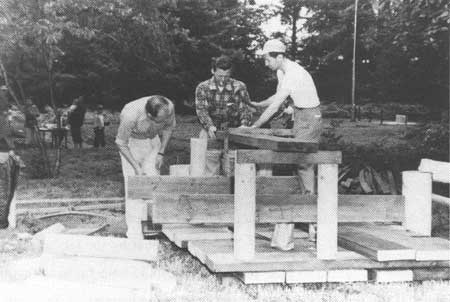

|

| Jaycees working on prefabrication construction, Astoria airport hanger, 1954. (FOCL photo collection) |

With the foundation laid, the replica was constructed at the site. Ruth Shaner, wife of Jaycee project manager Wes Shaner, Jr., remembers that by the last month of the project, her husband really had to push to get volunteers to help finish the replica. Many had grown tired of the project. In an effort to help get volunteers on Sundays, Ruth offered to teach Sunday school to the volunteers' children. [30] This did seem to help, but the project continued to the last minute. With dedication ceremonies planned for August 21, 1955, the Jaycees finished hanging the main gate on the morning of the 21st. A well, pump, picnic tables, and sanitary facilities were also completed during that month. Clatsop County graded the parking area and furnished rock for the parking area and access roads. The August 21 dedication ceremonies for the Fort Clatsop replica included the Secretary of the Interior and former Oregon governor, Douglas McKay; Oregon Governor Paul Paterson; Washington Governor Arthur B. Langlie; the presidents of the Astoria Chamber of Commerce and Junior Chamber of Commerce; Burt Brown Barker and Thomas Vaughan, the president and director of the Oregon Historical Society, respectively; and local boy scouts who arrived by canoe. During the ceremonies, Burt Brown Barker accepted the replica building on behalf of the Oregon Historical Society.

After the ceremonies and the Sesquicentennial celebration was over, site management problems for OHS had become much larger. Rather than merely a marked historical site, they now had a fort, sanitary facilities, and picnic areas to maintain. The Jaycees dropped any future plans they had for clean up and improvements at the site. Director Thomas Vaughn spent a weekend putting a chain link fence around the replica for protection. OHS worked with Burnby Bell to coordinate maintenance at the site. During the summers of 1956 and 1957, OHS was able to come up with a small amount of money to pay an attendant for the summer season to be at the fort during the day and open it up for visitors. Michael Foster was hired to staff the site during the summer of 1958. Foster spent seven days a week greeting visitors, cleaning the pit toilets, and selling souvenirs for the Clatsop County Historical Society, for which he received a small commission. [31] A donation box was placed at the site to help raise money for maintenance. Movement was already well underway to have the site taken over by the federal government.

|

| Jaycees working at site. Shown from left to right: Johann Mehlum, Wilt Paulson (smoking), and Joe Nerenberg. (FOCL photo collection) |

|

| Jaycees working at site. Shown from left to right: Johann Mehlum, Wilt Paulson (smoking), and Joe Nerenberg. (FOCL photo collection) |

The Salt Works Site, 1806-1978

One thing Captains Lewis and Clark intended to achieve during their winter encampment was the production of salt from ocean water. For that purpose, they sent a group of men to the coast. The saltmakers produced a total of about four bushels of salt, which the captains hoped would last them until they reached their caches of supplies along the Missouri River. Having the salt at Fort Clatsop was a benefit nutritionally and helped flavor elk meat that was already spoiling.

On December 28, 1805, Lewis and Clark sent "Jos. Fields, Bratten, Gibson to proceed to the Ocean at Some Convenient place form a camp and commence makeing Salt with 5 of the largest Kittles, and Willard and Wiser to assist them in carrying the Kittles to the Sea Coast". [32] From December 28 until their return to Fort Clatsop on February 21, 1806, the Salt Works operated continuously. The site was established near a village containing four houses of Clatsops and Tillamooks in what is today the town of Seaside, Oregon. The men camped in tents, near the mouth of the Necanicum River and "100 paces" from the ocean. [33]

|

| Seaside Lions Club constructing the Salt Works replica, 1955. (FOCL photo collection) |

From the journals, it is evident that there were always at least three men at the saltworks site, but the personnel did shift as necessary. George Gibson, William Bratton, and Joseph Field were stationed at the site most of that two months. While no description is given of the structure built for boiling ocean water, oral testimony about the site indicates stones were placed in an oven or cairn shape with one end left open. Working through the open end, a fire was built inside the stone oven and five kettles placed on the top. This testimony is derived primarily from stories passed down through the generations by Clatsops living during the expedition's stay and who witnessed the salt making. The captains report in their journals on January 5, 1806 that the salt makers could produce from three quarts to one gallon of salt a day, which means they were boiling approximately 40 gallons of sea water a day. [34] It was labor-intensive work, keeping the fire hot enough to boil the salt water and keeping up the supply of fire wood. The journals indicate also that the salt camp was extremely short on food most of the time and at least one hunting party was specifically sent out from Fort Clatsop to hunt for the salt camp. Lack of food, the constant labor demands, and more direct exposure to the weather than experienced by the men at the fort meant that by the beginning of February the salt makers were hit hard by illness. Gibson had to be carried back to the fort he was so ill and Bratton was plagued by lower back pains long after leaving Fort Clatsop for home.

The history of the salt works site is very similar to that of Fort Clatsop. As American settlers moved into the area, the salt works was reportedly still visible and a tradition of oral testimony developed as to the location of the site. The same trip of August, 1899, that brought Olin D. Wheeler to Fort Clatsop for its identification brought Wheeler to Seaside to locate the salt works. Wheeler and his party of locals, including Silas B. Smith, went to the site on August 28, 1899, where he reported that stones from the salt works "cairn" were still visible. Smith, the grandson of Clatsop Chief Comowool, reported that it was the site that his mother had pointed out to him as the place where the expedition made salt. [35]

On June 8-9, 1900, the representatives of the Oregon Historical Society who had Fort Clatsop identified travelled to the salt works site for the same purpose. OHS took along a Clatsop Indian woman named Jennie Michel, or Tsinistum, to help identify the site. She was 86 years old at the time. In a deposition for OHS, she stated that she had often been to the site with her mother and other Clatsops who had been alive in 1806 during the expedition's stay and was told this was the spot where they made salt. [36] Her testimony was corroborated by Judge Thomas A. McBride, who had grown up on the Clatsop Plains and had been shown the site by Silas B. Smith's mother. Judge McBride's visit to the site took place after Jennie Michel's, in December 1900. Just as they had done with the site of Fort Clatsop, the historical society documented the location of the salt works site, which was then being referred to as the Salt Cairn.

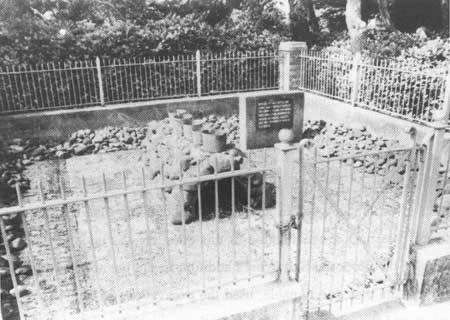

|

| Salt Works site just prior to construction of replica. (FOCL photo collection) |

After the 1900 visit, OHS had a fence installed around the ruins in cooperation with the site's owner. The site identified as the Salt Cairn was Lot 18, Block 1 of Cartwright Park, Seaside and the owner, Charlotte Moffett Cartwright, deeded the site to OHS as a gift to be held in "trust for the people of the State of Oregon for historical purposes only". [37] The deed was recorded on June 16, 1910.

By this time, Seaside had developed into a coastal resort town, a popular destination for vacationing Portlanders. In the 1920s, public interest continued in the Salt Cairn site. In 1925, the Great Northern Railway Company, whom Olin D. Wheeler had represented on his visit, along with the Spokane, Portland, and Seattle Railways, funded improvements at the site. Their goal was to provide a historical destination for railroad passengers. Landscape improvements included a sidewalk and an ornate iron fence placed on a brick foundation which enclosed the ruins.

Around the same time of Sesquicentennial celebrations and the building of the Fort Clatsop replica, the Seaside Lions Club began a replica project at the Salt Cairn. They hauled in stones and built a stone and cement cairn and placed five foundry kettles on top. Two bronze plaques described the site and its importance. Dedication ceremonies were held at the site during the Sesquicentennial celebrations of 1955.

The Seaside Lions Club maintained the site and provided policing efforts as well as they could. They sponsored clean-up projects at the site and the City of Seaside provided garbage service for one trash receptacle at the site. The volunteer efforts were limited, though, and the site was plagued by littering and occasional vandalism, with no site repairs being made. Interpretation at the site was never improved beyond the 1950s bronze markers. During the creation of Fort Clatsop National Memorial from 1956 to 1958, the saltworks site was never seriously considered for inclusion. At the time, the distance of the saltworks from the proposed memorial site was enough to discourage researching its authenticity and considering its inclusion.

During the 1960s, the Smithsonian Institution sponsored archeological excavations along the northern coast of Oregon. These excavations included the exploration of middens located in a golf course southeast of the saltworks site. These middens were believed to be the possible location of the Clatsop and Tillamook village the salt makers camped by. If those middens were the same village as mentioned in the journals, then the location of the saltworks camp would have been further south than the site owned by the historical society. No further examination of this question was undertaken. Several years later, opponents of the proposed Salt Works addition to the memorial, who felt that the authenticity of the site was questionable, used the excavations to support their position. Those who supported the addition of the site to the memorial maintained that further excavations would probably not reveal any evidence proving it to be the salt makers neighboring village or any evidence of the salt makers camp.

|

| Salt Works replica. (FOCL photo collection) |

From 1959 until its inclusion in Fort Clatsop National Memorial, the Salt Works site remained relatively unchanged, managed by the Seaside Lion's Club. In 1968, the Oregon Historical Society offered to donate the site to the National Park Service. With this offer, a ten-year debate over the addition of the Salt Works to the memorial began.

During the settlement of Oregon in the 1800s and into the 1900s, the sites of Fort Clatsop and the Salt Works held an attraction for the residents of Clatsop County and other Oregonians. The dedication and persistence of individuals in the local community and in the Oregon historical community, who felt that federal recognition was the best way to properly preserve Fort Clatsop and the Salt Works, eventually led to the creation of Fort Clatsop National Memorial.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

lewi/adhi/chap2.htm

Last Updated: 20-Jan-2004