|

Fort Clatsop

Administrative History |

|

CHAPTER FIVE:

DEVELOPMENT OF FORT CLATSOP NATIONAL MEMORIAL

In 1958, when Fort Clatsop National Memorial was created, the National Park Service was two years into a program called Mission 66. After World War II and into the 1950s, the National Park System experienced greatly increased visitation. Most parks were unprepared for these increases and park budgets did not provide for improvements and additional accommodations. Parks also suffered deterioration of existing facilities from overuse and age.

In 1951, Conrad Wirth replaced Newton Drury as Director of the National Park Service. Director Wirth began his term by strengthening ties with Congress and advancing the development needs of the National Park Service. This culminated in the Mission 66 program. Mission 66 aimed not only to rebuild park infrastructures to accommodate increased visitation and continued preservation, but it was also aimed at organizing and strengthening the Service. During the war years and the leadership of Director Drury, the Service experienced decreased budgets and increased pressures for the exploitation of park natural resources to aid the war economy. Postwar conflicts like one with the Bureau of Reclamation at Dinosaur National Monument threatened the legitimacy of Park Service policy in the face of other federal agency agendas. Mission 66 was intended to meet the demands of the public and to legitimize the agency's control and authority over the nation's parks.

To meet these goals, park and administrative facilities and roads were built or improved. The concept of the visitor center was developed, creating one building to accommodate visitor and administrative needs. One hundred fourteen visitor centers were built and 2,000 miles of roads built or improved throughout the National Park Service during from 1956 to 1966. [1] It was during this period of park development that Fort Clatsop National Memorial was created.

Lands

Public Law 85-435 provided for the creation of Fort Clatsop National Memorial and authorized the Secretary of the Interior to identify lands associated with Fort Clatsop, as well as portions of the overland trail from the fort to the coast, for inclusion in the memorial and to acquire those lands through purchase, donation, or other necessary measures. Fulfillment of the memorial's enabling legislation would be realized when at least 100 acres were in federal ownership. The task of identifying and acquiring lands for the park was the responsibility of the Region Four Office (Region Four was renamed the Western Region Office in 1962) in San Francisco. Region Four received assistance from the Western Office of Design and Construction (WODC) and the Columbia River Basin Survey Branch (CRBSB), a NPS field office in Portland, Oregon.

The lands identification process began with regional historian John Hussey's 1957 report. In that report, Hussey identified requirements for establishing a memorial at the site and suggested three possible boundaries. The boundaries established by Hussey took into account the re-creation and protection of the historic setting, the proximity of the existing county road to the site, the proximity of a neighboring residence, and needed administrative buildings. Hussey's minimum boundary recommendation called for a 32-acre site that included the fort replica, the canoe landing and mooring sites, the spring to the north, an area to the west for administrative buildings, and space to provide a screen between the fort and the neighboring residence. The second boundary recommendation called for 95 acres and included the neighboring residence and property, more land to the south for re-creation of the historic setting, and room to relocate the entrance and exit road and restore the bluff below the fort building, where the existing county road cut through, to its natural state. A third recommendation for 418 acres included acreage to the west and along the east bank of the Lewis and Clark River, visible from the fort site, for the historic setting and to provide a buffer from modern developments.

After Hussey's report and suggested boundaries were submitted to Congress in August 1957, Senator Neuberger drafted the enabling legislation for the memorial which would become law in May 1958. In the enabling legislation, Neuberger set a maximum acreage limitation of 125 acres. The reasons for this limitation are not clear. Correspondence between the NPS Western Regional Office and Washington D.C. show clearly that those involved in planning the park's development wanted to avoid a land limitation. From April 1957 to February 1958, correspondence regarding Hussey's suggested boundaries indicates that the Western Regional Office considered 100 acres as the minimum acreage acceptable for establishing the memorial and recommended leaving other lands identified in the boundary recommendations for possible future acquisition. Recommendations from the Assistant Regional Director to the NPS Director dated January 7, 1958, suggested a 100-acre minimum and stressed that if legislation was introduced in Congress for establishment of Fort Clatsop National Memorial, the Service should avoid having an acreage limitation written into the bill. A letter from Region Four Director Lawrence Merriam to the Director of the National Park Service dated February 13, 1958, advised that the acreage limitation be dropped from the Fort Clatsop bill. Merriam stated

In view of our past experience with historical areas, we are aware that such arbitrary maximum limits are frequently a severe handicap in the proper administration and development of historical parks and monuments. Witness our land problems at Cabrillo, Whitman, and Fort Vancouver. In the case of Fort Clatsop, we think such a limit would be particularly unfortunate, since we would be debarred from obtaining any really significant portion of the Lewis and Clark trail to the Coast even should it be donated to the United States. In our opinion, the greater part of the suggested 125 acres will be urgently required to protect the immediate vicinity of the fort site itself. Therefore, we recommend that an attempt be made to eliminate this provision from the bill. [2]

In determining why the limitation was created, it can only be assumed that it was necessary to ensure the success of the legislation. Correspondence indicates a hesitation on the part of those involved to introduce anything into the legislative process that would endanger passage of the memorial's enabling legislation.

On August 6, 1958, John Hussey completed "The Lewis and Clark Trail from Fort Clatsop to the Clatsop Plains, Oregon," a report in which he studied the identification and preservation possibilities of a section of the overland trail from the fort site to the Clatsop Plains. The enabling legislation for the memorial intended the inclusion of portions of the overland trail to the Pacific Coast used by the Lewis and Clark Expedition. Hussey concluded that 575 acres of timber lands could be obtained to protect the historical values of the trail portion and that such action would be desirable, provided that the necessary land acquisition did not adversely affect the lands acquisition process surrounding the memorial itself. The report also examined the possible inclusion in the memorial of a particular tract of forest land that belonged to the Crown Zellerbach Corporation. A news release issued from Senator Neuberger's office on June 22, 1958, reported that the Senator intended to discuss with the Crown Zellerbach Corporation the possible donation of a "segment of virgin evergreen timber stockading" [3] the trail to the Clatsop Plains. The tract was a stand of old growth hemlock located approximately 0.6 mile west of the fort site and consisted of about eleven acres. Hussey recommended no further consideration be given to this proposal. He dismissed the possibility of such a donation because of possible land use conflicts that would arise if the tract was obtained and the lands between the memorial and the 11-acre site continued to be owned by Crown Zellerbach. He also expressed doubts that the section of forest in question was truly old growth.

On August 19, 1958, the Division of Recreation Resource Planning, Region Four, submitted the "Boundary Study Report for Fort Clatsop National Memorial." The report was requested by Region Four Chief of Division of Recreation Resource Planning Ben H. Thompson to study boundary proposals for the park. Members of the planning team that developed the report were John Hussey, CRBSB Chief Neal Butterfield, WODC landscape architect Richard Barnett, CRBSB landscape architect Edwin L. Arnold, and CRBSB recreational planner Victor T. Ecklund. The report began by restating Hussey's first and second boundary proposals, for 32 and 95 acres respectively, to preserve the fort site and some of the historic setting. The planning team recommended two additional proposals which included the site and historic scene, relocation of the county road, the necessary visitor and administrative facilities, parking, employee housing, and utility facilities. Their first recommendation utilized 125 acres, which provided for the road relocation, visitor and parking needs, minimum residential and utility needs, and minimum protection against future incompatible developments. Their second boundary recommendation was for 418 acres, which provided for additional protection of the site and historic scene, inclusion of necessary facilities, and buffers against future developments.

The planning team also considered Hussey's trail to the Clatsop Plains proposal. While they agreed with Hussey's recommendations for preserving a portion of the overland trail, they recommended not pursuing the trail proposal until such time as the memorial legislation would not be endangered. On August 19, 1958, Acting Regional Director Herbert Maier recommended to the NPS Director that the trail be made a separate consideration so as not to complicate the memorial objective. The trail proposal was left for future consideration. Although the enabling legislation was signed into law with the 125-acre ceiling, the planning team continued to recommend plans for a larger park, arguing against the limitation.

The regional planning division, working in conjunction with the Portland field office and WODC, identified eleven tracts of land, totaling 124.97 acres, to complete the first boundary proposal in the study report. Sixteen tracts were identified that would have completed the second boundary proposal of 418 acres. [4 ] The Portland field office worked with Clatsop County offices in establishing possible boundary lines. Consideration was given to existing property lines and developments, topography, the best possible relocation of the county road, necessary facilities, and historic site protection.

On March 11, 1959, Director Conrad Wirth designated the planning team's first proposal of 124.97 acres as the official boundary of the memorial and authorized the regional office to proceed with acquisition of identified tracts, making additional adjustments as necessary, as long as the 125 acres was not exceeded. The Secretary of the Interior approved this designation and the regional office proceeded to acquire the eleven tracts. With the official designation of the memorial boundary, the debate over additional land acquisition was ended.

In addition to having to deal with the individual land owners, the Park Service had to deal with a number of separate rights attached to the properties in question. Clay and mineral rights, railway rights, diking rights, road rights, prospecting rights, and easement rights to Pacific Power and Light for power lines all pertained to the various tracts identified. Most of the tracts had a combination of different rights attached to them.

Of the eleven tracts identified, five tracts totaling 21.2 acres were donated. They included: tract #8 donated by the Oregon Historical Society, including the fort replica; tract #1 donated by Clatsop County; tract #2 donated by the Clatsop County Historical Society; and tracts #3A and 3B donated by the Crown Zellerbach Corporation. Senator Neuberger was again a major influence in the development of the memorial by suggesting and encouraging the president of Crown Zellerbach to donate land for the memorial's establishment.

The remaining six tracts, totaling 103.77 acres, were purchased from neighboring land owners. They included: tract #6 owned by R.J. and Jean Kraft; tract #7 owned by Kenneth and Ruth Miller, including a house; tract #5 owned by J.K. Roberts; tract #9 owned by Archie Riekkola; tract #10 owned by Elmer and Barbara Miller, which included a barn; and tract #11 owned by Otto and Alice Owen. Total cost for purchasing the six tracts was $46,150. [5] In October 1962, the Secretary of the Interior announced that the 124.97 acres of the memorial had been donated or purchased.

In all, nine rights (two mineral, four clay, and three railway) were obtained, all through quitclaim donations. Quitclaim donations were given by Gladding, McBean, and Co. (who held most of the clay rights), Crown Zellerbach, and Clatsop County. Clatsop County also quitclaimed rights to all county roads and trails within the memorial boundaries. All rights to memorial lands are currently owned by the federal government.

One year after the final papers were cleared for all land purchases, Mrs. Alice Owen offered to sell the remainder of the Owen tract to the memorial. In the creation of the memorial, the Park Service had purchased only a portion of the Owen property. Shortly after the purchase, Mr. Owen passed away and Mrs. Owen desired to sell the rest of their property, consisting of 79 acres. Superintendent Charles Peterson informed the regional office about the offer and inquired about the possibility of purchasing the land. The answer was negative. Purchasing the 79 acres meant not only finding the funding but also getting amendatory legislation through Congress to increase the memorial's acreage ceiling.

The memorial's inability to purchase the 79 acres would later cause a public relations problem. In 1970, Robert J. Hjorten, owner of the property, inquired if any road rights-of-way were maintained by the Owens in their sale to the Park Service. In 1961, when the Park Service relocated the county road, the Owens' road was obliterated and they apparently reached the remainder of their property through a private neighboring road. Around 1972, Hjorten requested permission to build a 100-foot road from the county road to his property that would have cut through the far northwest corner of the memorial property. Superintendent Paul Haertel reviewed the proposal and referred it to the regional lands division. Upon further investigation, the service learned that Clatsop County had reserved a public use right-of-way from the old U.S. Highway 101 inward to the Hjorten property. This meant he had the ability to build a 1400-foot road. Because he had legal road access, the service rejected his proposal.

A few years later, Hjorten countered by offering a land exchange. He proposed exchanging a strip of his property adjacent to the western edge of the memorial boundary for an equal amount of land from the northwest corner of the memorial property. The exchange would have allowed Hjorten to build the 100-foot road he had proposed earlier without cutting through memorial lands. Superintendent Bob Scott recommended acceptance of the proposal, but the regional office was not receptive. However, the Park Service never had to make a decision regarding this offer. In November 1978, Hjorten conveyed his property to the Publisher's Paper Company. The eight-year wait was frustrating for Hjorten, who claimed he could not develop or sell the property without a road. Hjorten had written to Senator Mark Hatfield in 1975 requesting assistance in dealing with the Park Service. Senator Hatfield inquired about the matter on his behalf, questioning why an agreement had not been reached. After eight years with no resolution, Hjorten rid himself of the property, probably due to the inability to reach a compromise with the Park Service.

The memorial's land holdings changed for the first time when the National Parks and Recreation Act of 1978 passed Congress and the Salt Works site in Seaside was officially added to the memorial. This legislation amended the memorial's enabling legislation by increasing the acreage ceiling to 130 acres. The addition of the 100-by-100- foot city lot was donated to the Park Service by the Oregon Historical Society on June 23, 1979. The addition raised the total acreage of the memorial to 125.2 acres.

In 1989, Fort Clatsop was offered approximately 32 acres on the west side of the Lewis and Clark River and adjacent to the memorial's western boundary for $32,000. The property belonged to Cavenham Forest Industries, who acquired Crown Zellerbach assets in May 1986 and continues to own the timber property to the west of the memorial as a division of Hansen Natural Resources Company, a conglomerate headquartered in Great Britain. Superintendent Frank Walker informed the regional office of the offer and inquired about the possibility of acquiring the land. Other parties were interested in acquiring the property and the issue of external threats to the memorial through the development of this property had to be addressed. Superintendent Walker favored the acquisition, but the regional office responded negatively for the same reasons the Owens' offer had been turned down in 1963. Superintendent Walker then contacted the Nature Conservancy of Oregon in hopes the organization could purchase the property. When the Nature Conservancy also declined the offer, the Fort Clatsop Historical Association began negotiating with Cavenham to purchase the property. The cooperating association board agreed acquisition of the property was in the best interest of the memorial, protecting it from incompatible development. Chairman Michael Foster contacted Cavenham Industries and negotiated the land purchase. The association purchased the 32 acres for $16,000, half the assessed value of the property, with the intent to donate the land to the memorial at a later date. FCHA continues to hold the property until amendatory legislation raises the acreage limitation and the memorial can incorporate the property.

Site Development

In 1960, the creation of an administrative staff for the memorial began. Charles Peterson, formerly the Assistant Superintendent at Morristown National Historical Park, became the first superintendent of the memorial on May 29, 1960. On September 30, 1960, Fort Clatsop National Memorial became an official administrative unit of the National Park System. In October 1962, the 124.97 acres identified by the planning team as the best possible acquisitions for the memorial's establishment were vested in federal ownership. The Secretary of the Interior issued a public statement declaring the memorial formally established pursuant to P.L. 85-435 (72 Stat. 153).

Beyond the proposal and successful campaign for creation of a national park unit, National Park Service staff become involved in the development of a concept for that park's design and function. For Fort Clatsop, that concept was begun by John Hussey in his Suggested Historical Area report of 1957. His idea for a memorial at the site was shaped by Mission 66 development policies and visitor use attitudes. Hussey recommended that a memorial at the Fort Clatsop site interpret the historic Lewis and Clark Expedition through the use of the fort replica and the re-creation of the historic scene. Hussey recognized the need for a visitor center, providing visitor facilities, interpretive exhibits, and administrative offices. He recommended the relocation of the county road and the acquisition of buffer areas to protect the historical integrity from residential and commercial developments that were "becoming more prominent." [6] Hussey stressed acquisition of enough property around the fort site for adequate building and parking space, but also for the re-creation of the "atmosphere of primeval forest which should be created around the actual fort site." [7] It was John Hussey who first imagined the memorial as a park where the visitor could learn about the Corps of Discovery through interpretive media in a visitor center and then be able to walk to the fort replica and experience a change in environment, from the modern to a re-creation of the environment that the Expedition experienced.

Site development involves the implementation of the design concept prepared for a park unit. The planning team directed to establish boundaries for the memorial, working under the acreage ceiling, selected lands around the fort site that allowed for development of the memorial. After acquiring title to those lands, the process of achieving the suggested historical area report's concept for Fort Clatsop National Memorial began to develop.

From 1960 to 1965, the period of Charles Peterson's term as superintendent, four projects formed the genesis of the memorial as an operating unit of the National Park Service. These four projects were: the relocation of the county road, the development and building of the visitor center, the remodeling of the fort replica, and the creation of a park master plan.

Relocation Of Fort Clatsop Loop Road

In 1958, the county road passing the Fort Clatsop site, the Fort Clatsop Loop Road, cut through the ridge between the fort site and the Lewis and Clark River, past the canoe landing and mooring site. A small access road and parking area were located next to the fort replica. If the memorial was to re-create the historic scene of 1805-1806, the road would have to be moved. NPS Director Conrad Wirth agreed with this assessment when he viewed the site from the air in 1958. [8]

The Region Four planning team, in deciding the memorial's boundaries, did so with consideration of the road relocation. They chose to shift the county road north and west, about to the edge of the proposed northern and western boundaries. The existing road would then be demolished and the strip of land returned to its natural state. The Park Service would control the section of Fort Clatsop Loop Road passing through the memorial's boundaries. In purchasing land from Clatsop County, the Park Service required Clatsop County to quitclaim all rights to roads and trails on the property. The Park Service also requested a Memorandum of Understanding with the county for maintenance of the section of Fort Clatsop Loop Road to be built. The Clatsop County commissioners were at first reluctant to accept this arrangement and did not want to quitclaim the county's right-of-way. The Commissioners were concerned with their status in the maintenance agreements and the quality of the reconstructed road section.

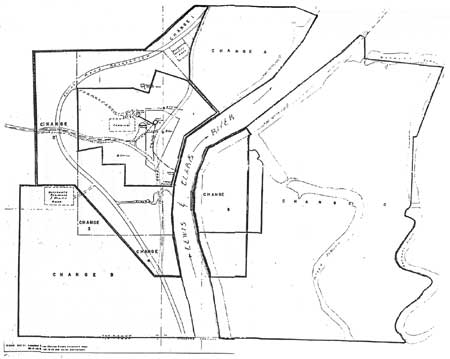

|

| 1960 map showing the relocation of the county road. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

Because a good portion of the lands surrounding the memorial were timber lands owned by timber corporations, the county road was used heavily by logging trucks. The county commissioners wanted assurances from the Park Service that the reconstructed road would be able to handle the weight of loaded logging trucks and not interfere with their use of the road. In addition, the county also was concerned about memorandum agreements with the Park Service (which would be revocable) and the source of funding for any future construction. On August 14, 1961, the Clatsop County Engineer approved the road design for the relocation. The Clatsop County Commissioners then agreed to the quitclaim arrangement, providing that the agreement contain the statement that the county would not be responsible for the costs of any future construction. [9] The quitclaim deed was recorded October 13, 1961. [10]

Following the agreement with Clatsop County, road relocation began. The construction contract was awarded to a local construction company, Grimstad and Vanderveldt, Inc. During the construction period, not only would the new section of road be completed, but all entrance and exit roads and parking areas as well. An entrance/exit road from Fort Clatsop Loop Road to the parking area and visitor center location was constructed, as well as an entrance road to the memorial's residence #1 (the house purchased from the Millers), a spur road to residence #3 (employee residence to be built by the Park Service), a spur road from Fort Clatsop Loop Road to the utility structure, and parking areas at both residences, the utility structure, and visitor center parking. The visitor center parking area provided for twenty-seven cars, with three additional bus and trailer spaces. The original parking plan provided for only fourteen cars. Superintendent Peterson recommended the increase and tried to increase the parking area further just prior to the completion of construction. In all, 7,407 feet of road and 2,366 square yards of parking were constructed and completed by July 1962.

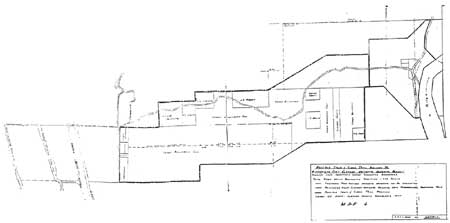

|

| View of entrance to fort replica from county road, 1958. (FOCL photo collection) |

Since the original construction of the memorial's roads, the parking area has been upgraded three times and spur roads behind the visitor center developed and paved. The memorial continues to hold a Memorandum of Understanding with Clatsop County for minor road maintenance.

The contract with Grimstad and Vanderveldt, Inc., was modified during road construction to include the razing of certain structures to make way for the construction of new memorial buildings. The Miller barn, corral, and shed which lay in the path of the new road, and the Kraft's shed and corral which was visible from the entrance road, were eliminated. The ruins of the canoe landing site dock, previously owned by the Crown Zellerbach Corporation, were also removed.

Building Construction

As discussed earlier, Fort Clatsop was developed during the Mission 66 period of the Park Service which meant an emphasis was placed on planning for a single building for administrative and visitor needs. The site's rural location required construction of necessary visitor and administrative facilities. The Region Four planning division determined the memorial would need a visitor center, at least one employee residence, and a utility structure. In purchasing the Miller residence, the memorial would already have one two-bedroom house available for employee housing. Funding was made available to build one additional employee housing unit.

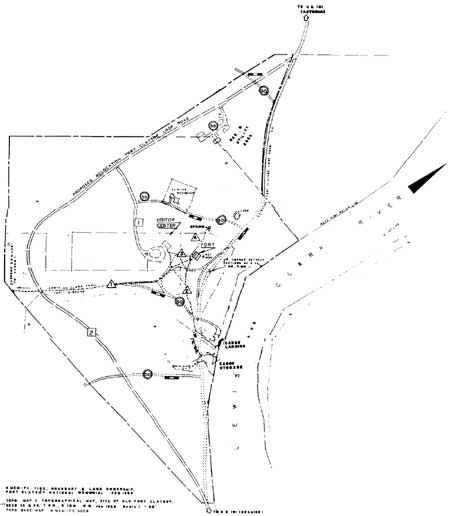

|

| The completed Fort Clatsop National Memorial, 1963. (FOCL photo collection) |

A contract was awarded in March 1962 to the McLinn Construction Company of Tacoma, Washington, for the construction of the visitor center, one three-bedroom employee residence, and a utility shop. McLinn brought in the lowest bid of $103,281. The visitor center building was designed to hold administrative offices for the park staff, an exhibit hall and auditorium for interpretation, a visitor information and sales counter, and other visitor facilities. The visitor center was designed by the WODC office in conjunction with the park staff. The structure was 3,300 square feet. It contained three offices, a combination mail/break room, and a small 36-seat auditorium. The structure was typical of the Mission 66 era visitor center construction. The three-bedroom residence was built at the north end of the memorial. Near the employee residence, a small utility structure was built for use as a maintenance facility and storage unit.

|

| View of path from visitor center to fort replica, March 1963. (FOCL photo collection) |

All construction took place between June 30, 1961, and January 1963. Special use permits were obtained for utilities and lines installed. Public dedication ceremonies for the visitor center were held on August 25, 1963, which also marked the 47th anniversary of the National Park Service.

Restoration Of The Fort Replica And Its Historic Scene

In considering the site of Fort Clatsop for national memorial status in 1955, an important issue for the Park Service was the accuracy of the replica. The use of replication and restoration in the interpretation of America's historic sites and the proper application of these mediums has been debated by Park Service historians since the NPS incorporation of national historic sites under the 1935 Historic Sites Act. The problems of legitimacy and accuracy in replications troubled the Park Service from the beginning at the George Washington and Abraham Lincoln birthplace memorials. Both sites were received by the Park Service with erroneously replicated buildings. With regards to Fort Clatsop, it was important to the park service that the goal of historical accuracy and the presentation of the Lewis and Clark Expedition would not be compromised by faulty reproduction.

When national memorial status was granted to Fort Clatsop, research to improve the historical accuracy of the replica began with the 1959 Historic Structures Report and Furnishings Plan, Part One. The report consisted of six sections: administrative data, prepared by John Hussey; historical data, prepared by historian Carl P. Russell [11] architectural data, prepared by Charles S. Pope; archeological data, prepared by Paul J.F. Schumacher; landscape data, prepared by landscape architect Harold G. Fowler; and the furnishings data, also prepared by John Hussey.

In the administrative data section, Hussey listed the report's conclusions. In the context that the replica would be used as a historic exhibit, it was determined that

the existing log shell...will require reconstruction to remove elements admittedly not now historically accurate and to add features to bring the structure into conformity with what is known concerning the original Fort Clatsop built by Lewis and Clark in 1805-06. [12]

Hussey estimated the reconstruction would cost $17,000 for all materials, labor, surveys, plans, and supervision. Since the 1960 fiscal year budget included $8,000 for the memorial, Hussey requested an additional $9,000 be allocated. [13]

The historical data for the fort replica was compiled mainly from the examination of the Expedition's journals. Carl Russell examined this documentation for any information regarding the physical nature of the structure, the construction methods used, the resource materials available to the Expedition at the site, the tools and equipment in the Expedition's possession, and type of furnishings constructed. Russell researched William Clark's involvement in the construction of other frontier forts, both before and after the Expedition, looking at the style of construction with which Clark seemed familiar. Russell also examined the journals and notes regarding the building of the Expedition's 1803-1804 winter quarters, Fort Mandan, completing a sketch of the Fort Mandan structure from that documentation.

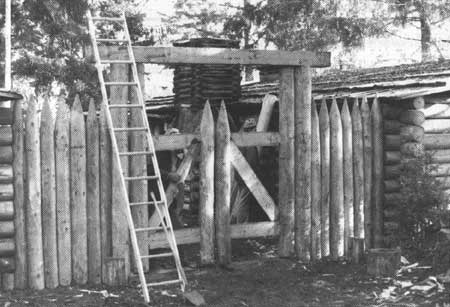

|

| Memorial staff hanging reconstructed main fort gate, July 1964. (FOCL photo collection) |

From all these sources, Russell gave his estimation of the materials and construction styles used in building the fort. For example, Russell concluded that the party probably did not peel the logs for the fort, that little shaping of the logs was done, and that there was no conclusive evidence of what style of corner notch was used in construction. Russell also discussed the tools used by the Expedition and how their use would have affected the construction style and look of the fort. The style of furniture was also examined and Russell included sketches of what he believed the furnishings looked like. Appendix B of the report listed tools and food stores.

Finally, Russell compared the replica to the data he had compiled and recommended several improvements for making the replica more representative of the available data. Briefly, these were:

Provide earth fill to hide the exposed concrete foundation of the replica.

Stain the logs to replicate a natural weathered look. The wolmanization process had caused a yellowing of the replica logs.

Use a clay plaster mix utilizing clay deposits on site to daub between the replica logs. No daubing had been done on the replica and the Expedition journals specifically mention "chinking and daubing" in constructing the original fort.

Replace the cedar shake roof with hand-hewn plank roofing.

Install wood gutters to conceal the existing gutters. Russell felt that with public use, methods should be used to keep the parade ground from turning into a quagmire.

Create smoke vents in ceiling of rooms with central fireplaces.

Build a fireplace with exterior chimney for the captain's quarters.

Make and install hand-hewn plank flooring for rooms.

Create central fireplace pits for rooms with central fireplaces.

Create half lofts for storage in captain's quarters and at least two enlisted men's rooms.

Make doors for all doorways.

Construct a sentry box loosely resembling a small outhouse without a door. However, Russell recommended not building the sentry box without giving an explanation.

Install the water gate, or second gate, in the back corner of the parade ground. A wood pile for firewood supply should be kept outside this gate.

Replace or conceal iron hinges on main gate.

Cover the parade ground with fill to prevent quagmire of mud.

Construct crude furnishings, bunks, tables, and chairs, and lay out examples of items the Expedition used.

In completing his recommendations, Russell gave examples of other Park Service reconstruction projects, such as the reconstructed army hut at Morristown National Historical Park, for comparison and construction data. [14]

In conclusion, Russell stated that if the Park Service were to build a replica of the Fort Clatsop structure from scratch, it would probably be rougher and have less concern with permanency than the existing replica. The "most glaring" errors of the replica, according to Russell, were the close fitting logs and the perfect vertical lines at the corners, which could only be corrected by completely rebuilding the replica. Due to the time and effort of the many local people and organizations in building the replica, Russell acknowledged it would be difficult to justify tearing it down and rebuilding. He advised the Park Service could do good interpretive work at the site if the "mark of the American backwoods craftsman" was evident. [15]

Architectural data consisted of the working drawings by local architect John Wicks which had been used in constructing the replica. WODC architect Charles S. Pope completed architectural drawings for the possible reconstruction projects listed by Russell in the historical data section. The construction projects detailed in Pope's drawings were covered by Russell in the historical data section.

Archeological data consisted of a review of past excavations done at the site and recommendations for further study. Paul Schumacher recommended subsurface excavation prior to completion of the landscape work. Schumacher estimated that with the use of a backhoe [16], the work could be completed in two to four days at a cost of $1,000. Schumacher also recommended dating materials from firepits located during his 1957 excavations by a new thermoluminescent dating process.

Landscape data consisted of recommendations for preparation of a design and plan for the landscape at the site. Fowler determined the journals had been sufficiently researched through the site determination process. He suggested an examination of existing virgin Oregon coastal forest to determine the general appearance needed at the memorial. He recommended that WODC prepare the landscape plans at the same time that design plans for the replica restoration were completed.

Fowler gave several recommendations for those plans. He suggested that the landscaping in the vicinity of the replica and at the overlook onto the Lewis and Clark River should re-create a wilderness atmosphere. The visitor center and parking should be screened by using not only native conifer species, but also native deciduous trees such as alder. All additional plantings should be done to supplement the existing conifers and a dense forest should be avoided due to the darkness it would create. [17] Screens around the overlook onto the river and Saddle Mountain would be done only to conceal physical structures. Finally, the trails to the canoe landing, spring, and eastern section of the trail to the coast should be re-established.

In the furnishings data section, John Hussey refers back to Carl Russell's historical data report. Russell also was preparing the Preliminary Exhibit Plan for the fort replica, which provided supplementary data to his historical report. Hussey recommended following Russell's suggestions and using those guidelines as the replica's furnishings plan. He estimated that $5,800 of the $17,000 projected remodeling cost would be used for replica furnishings.

This 1959 report constituted the preliminary data for the replica reconstruction. Part I was intended "to be a clarification of the scope of work, the coordination and resolution of the various investigations, and the definitions of guides for the work to be done in Part II" [18] Part II, completed December 1962 and approved by the regional office in April 1963, outlined decisions regarding the replica restoration, responding to further investigations into the feasibility and authenticity of recommendations from Part I.

Part I was reviewed by the regional office, the WODC office, and the Washington D.C. office. Superintendent Peterson made many contacts, both inside and outside the Park Service, for data and opinions regarding the recommendations in Part I of the Historic Structures Report. He consulted with other parks containing reconstructed log structures, including his previous work station Morristown National Historical Park, and with Lewis and Clark historians. Other sources consulted regarding the original structure were the OHS depositions from 1900 and the 1957 interview with Harlan Smith.

Part II of the Historic Structures Report and Furnishings Plan was much more refined. Specific actions and purposes in remodeling the replica structure were outlined. The report was again divided into six sections: administrative; historical; architectural; archeological; landscape; and furnishings data. This report was completed mostly by Superintendent Peterson and park historian Burnby Bell, incorporating review comments and additional research completed during the interim.

Administrative data presented the proposed use and provisions for operating the replica as a house museum. The replica was identified as Building #4, category III, work code 7. The replica was to be "reconstructed, furnished, and used as a historical exhibit." In furnishing the replica, it was to look as it did the day the Expedition left. Considering theft and vandalism, the planners did not feel secure in furnishing the replica with items representative of everyday life at the fort. During the summer season, one or more seasonals would be at the fort and provide visitor interpretation. For the off-season and times when no ranger was available at the fort, an audio station would be installed to provide a taped interpretive narration. Approximate hours of operation were 9 A.M. to 9 P.M. during the summer and 9 A.M. to 6 P.M. during the off-season. The estimated cost for the remodeling project remained at $17,000, including the cost of the audio station. [19]

The historical data section, in summarizing the historical data report completed by Carl Russell and the continuing research done by the park staff, stated that the floor plan and some details of the replica conformed to the data available in the Expedition journals. "All other work done and to be done is based on conjecture and contemporary structures, and is representative of the summary beliefs of individuals who have performed research for the project." [20] The report also presented information regarding the north-south directional placement of the fort. In examining the 1900 OHS depositions as well as the 1957 Smith interview and subsequent correspondence with Harlan Smith, the planners determined that the fort most likely was placed in an east-west direction rather than the replica's north-south placement. The cost of reorientation of the replica was estimated at $9,000 for construction and $1,500 for overhead if done prior to the reconstruction, and two to three times that amount if done afterward. Overall, the planners stated that the current orientation of the replica was satisfactory from an interpretive standpoint.

The architectural data section presented modified recommendations for the replica remodeling. The recommendations made by Carl Russell in Part I were restudied and re examined for their feasibility and necessity by Park Service planners. Most of the original recommendations were modified.

Recommendations for covering the concrete foundation, building half lofts in the cabin rooms, and building the fireplace and chimney in the captains' quarters remained the same. All the other recommendations were modified, most only minor changes to the design or materials suggested. The most significant changes included closing the "gun ports" located in the outside walls of the replica. Windows looking into the parade ground were to be cut and the log material taken out used to patch the gun ports. Daubing was to be done only in select spots, not all over the replica. Plans for central fireplaces and roof vents were eliminated for all but the meat room. The sentry box would be built and used to house the visitor-activated audio narration unit. All rooms and the parade ground were to be excavated with drain lines and a gravel base with shredded bark cover for proper water drainage. Gutters were to be placed only over doorways.

|

| Construction of the exterior fireplace for the captains' room, July 1964. (FOCL photo collection) |

It was determined that all reconstruction work should be done over an extended period of time in order to allow visitation to continue with minimal disruptions. An order in which to complete the projects was established. The creation of parade ground windows and the closing of the gun ports received top priority, followed by the construction of the chimney for the captains' room. This was followed by the construction of the water gate, the reconstruction without iron hinges of the main gate, drainage ground work, construction of the sentry box, completion of the fireplace in the captains' room, the construction of firebacks in the enlisted men's quarters, the central fireplace in the meat room, re-roofing, construction of doors, flooring, and lastly, half-lofts and shelves.

The park staff concluded that reorientation of the replica was not feasible and that not enough evidence supported a reorientation. With regards to the "mechanically perfect" construction noted by Carl Russell in Part I, it was concluded that weathering had softened the appearance of the replica and no additional work to roughen its appearance would be necessary.

The archeological data section of Part I had suggested further excavations with a backhoe before remodeling projects began. The excavations were carried out during the summer of 1961 and the results presented in Part II of the study. The excavations were again completed by Paul Schumacher.

During these excavations, firepits were uncovered and material from mid-to-late nineteenth century settlement were uncovered. No evidence of the Lewis and Clark Expedition was found. The report concluded that historical evidence was strong enough to substantiate the site's location and that no further excavation work needed to be done, except for monitoring of future ground-breaking construction. The report also stated that excavation work would be complicated by the amount of tree roots lying underground, which would have destroyed any evidence. [21]

The landscape data section referred to the park master plan being written by the park staff. Volume I, Chapter 5, outlined the design plans for landscaping the memorial. The area around the fort replica was targeted for replanting as well as the location of the old county road, areas between the replica and modern buildings on site, and large open field spaces to the south of the replica. Native tree and plant species were to be used.

Finally, the recommendations for furnishing the replica were outlined in the furnishings and exhibition section. Each individual room was listed with the furnishings to be constructed for each. The three enlisted men's rooms were to be furnished with tables and benches, a gun rack, and four bunks, each two beds high. Room #2 was to have a tree stump with stools in place of the table and benches. This was derived from the oral testimony of settlers documenting the site, who reported that a large tree stump was located in one room of the fort and used as a table. There is no mention in the Expedition journals to any stump. The meat storage room was to have overhead poles and wall pegs used for the hanging and drying of jerky. The orderly room would be furnished with a table, two benches, two bunks, and a gun rack. The captain's room would have a large table, two chairs, two drawing boards, two single beds, and two shelves. The Charbonneau family room would be furnished with a low double pallet, a small table, and two chairs. In the parade ground, a period flag would be flown and outside the water gate a large utility table would be placed.

The goal in furnishing the replica was to make it look as it did when the Expedition left and gave the fort to Chief Comowool. Park administration determined that the risk of theft and vandalism was too great to be able to present replica objects that would have been carried and used by the Expedition. Replica furnishings would change as the park's interpretation programs developed.

Reforestation to re-create the forest atmosphere that would have existed during 1805-1806 initially centered around the fort replica and between modern construction, as identified in the landscape sections of the historic structure reports. Tree and plant species identified by Lewis and Clark in their journals and other sources describing the plant life of the early nineteenth century were to be used to determine what species to plant. Planting around the fort replica was postponed until after reconstruction work was done. Emphasis was placed on the restoration of the old county road area on the east side of the replica and supplementing the second growth trees already in existence. Tree screens were begun in 1962 around modern construction by transplanting young trees from other areas on the memorial grounds. Planting efforts also occurred along trails constructed to the canoe landing and spring. Reforestation continued later in various stages to fill in areas identified in the 1964 Master Plan.

1964 Master Plan

The final task to make the memorial a fully functioning unit of the National Park Service was the creation of a master plan document for the site. This was begun in 1959 by John Hussey. When Superintendent Peterson started on June 27, 1960, he continued progress on the park's master plan. Work on this document continued from 1960 until it was approved in 1964. The purpose of Fort Clatsop National Memorial, as defined by the 1964 approved Master Plan, was "to provide opportunity at this authentic site for visitors to gain knowledge and inspiration from the story of the Lewis and Clark Expedition; and to provide awareness of the significance of this epic feat of exploration in winning the west for the United States."

The National Park Service used six service objectives for the management of park units. They were:

I. To provide for the highest quality of use and enjoyment of the National Park System by increased millions of visitors in years to come.

II. To conserve and manage for their highest purpose the natural, historical, and recreational resources of the National Park System.

Ill. To develop the National Park System through inclusion of additional areas of scenic, scientific, historical, and recreational value to the nation.

IV. To participate actively with organizations of this and other nations in conserving, improving and renewing the total environment.

V. To communicate the cultural, inspirational, and recreational significance of the American heritage as represented in the National Park System.

VI. To increase the effectiveness of the National Park Service as a "people serving" organization dedicated to park conservation, historical preservation and outdoor recreation.

Within these six service objectives, the master plan defined how the park would operate to meet those objectives:

I. To encourage visitor use and enjoyment of the park's historic, scenic, and natural resources. This was to be achieved through the maintenance of historic trails to the river, the ocean, and other historic sites; and by identifying examples of natural resources along trail routes and providing natural history interpretation at the visitor center. The park would perform historical research to provide knowledge for interpretation, preservation, and authentic reconstruction.

II. To maintain the historic setting through careful reconstruction and the use of screen plantings, proper curatorial care of the fort replica, and the separation of new developments from historic exhibits.

III. The master plan did not call for additions to the park, stating that existing boundaries were adequate for developmental needs.

IV. To cooperate with federal, state, and local agencies in resource conservation and encourage land use and development harmonious to the park through the appreciation of the park by the local community.

V. To interpret the Lewis and Clark story for the visitor, making sure the interpretation is appropriate for all types of visitors to the park, and to update and improve the interpretation program and facilities as needed. The fort replica and surrounding grounds would be used to make clear the conditions under which the expedition camped.

VI. To promote the training of permanent and seasonal staff as available and the use of appropriate NPS management guides and tools.

The master plan outlined possible future management programs for Fort Clatsop. These projects were divided into three categories: lands, staff, and visitor needs. The plan identified two program needs as land issues: tree planting to create screens between the fort scene and modern improvements to foster the historic scene, and the development of a maintenance program to preserve the new construction. Numerous visitor needs were identified. Among them was improving the parking lot to hold an additional four busses and 18 cars; replacing the pit toilets near the picnic facilities with a modern restroom; remodeling the information and sales counter in the visitor center; enlarging the audiovisual theater to hold at least twice the present capacity; preparing and printing a historical handbook; installing better signs on Highway 101; developing an audio interpretation station at the canoe landing; creating a display of Indian artifacts related to the Expedition; installing more picnic tables; providing for park staff living on site for security; and training park staff in visitor safety. Finally, staff needs consisted of using training opportunities as they became available; executing regular maintenance programs; and enlarging the maintenance utility structure.

The 1964 master plan dealt primarily with visitor needs that became apparent shortly after completion of the visitor center. The need for a larger auditorium, increased visitor parking, and larger picnic facilities were the most ambitious programs identified. Originally intended to last for ten years, thirty years passed between the completion of the memorial's master planning document and the preparation of a new general management plan, completed in 1995.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

lewi/adhi/chap5.htm

Last Updated: 20-Jan-2004