|

Fort Clatsop

Administrative History |

|

CHAPTER SEVEN:

RESEARCH AND RESOURCE MANAGEMENT

Fort Clatsop National Memorial was designated by Congress to commemorate the Lewis and Clark Expedition, a significant event in the history of the United States. In considering resource management at Fort Clatsop National Memorial, there is no dividing line between cultural and natural resources, which are intrinsically linked. The entire memorial is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. The natural environment encountered by the Expedition and recorded by Captains Lewis and Clark is very much a part of the memorial's main cultural resource: the story of the Expedition.

Resource management at the memorial has historically been the responsibility of the interpretation and maintenance staff, with no designated resource management position or formal program. The primary documents guiding resource management at the memorial have been the 1964 Master Plan and its Resources Management Plan, written in 1973 and revised in 1984 and 1986. These documents guided management in the memorial's reforestation efforts, forest maintenance, and in the maintenance of its cultural resources. With the creation of a resource management program in 1992, the management needs of memorial resources, for their future protection and maintenance, will be identified in a revised Resources Management Plan.

Cultural Resource Management

Cultural resource management needs primarily focus on maintenance of the fort and salt works replicas, the memorial's natural and cultural collection, its photograph and slide collections, and library collection, including 156 rare volumes. Three archeological excavations have failed to reveal conclusive evidence of the original fort structure, but they have revealed the location of a 19th century home and artifacts of 19th century settlement. Of the people who have worked at the park over the years, each has their own theory and opinion about the possible existence and location of any evidence of the original fort.

Louis Caywood, 1948

The first excavation was completed in 1948 by National Park Service archeologist Louis Caywood. The site still belonged to the Oregon Historical Society, who arranged for assistance from the Park Service in carrying out an excavation. Speculation about the authenticity of the site had grown since OHS' identification of the site in 1900 and the society hoped to verify the site through archeological excavation.

|

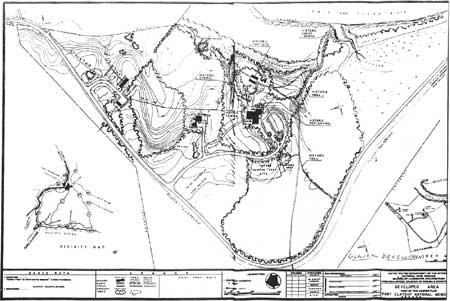

| Map of Caywood excavation, 1948. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

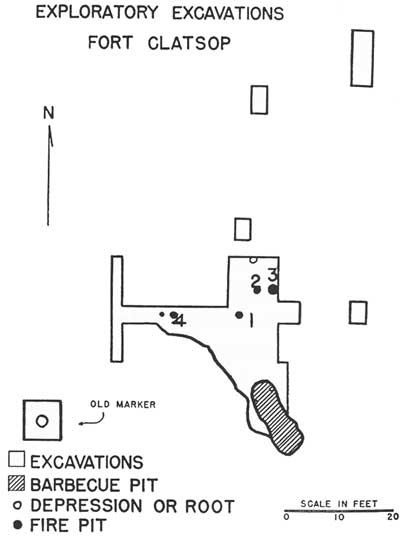

Caywood's excavations were quick and incomplete, in part due to lack of available labor, and in his words were "not as comprehensive as had been hoped." [1] What Caywood uncovered were four fire pits and one rather large pit which he described as a barbecue pit. Materials from these pits included animal bone, charcoal, and two pieces of wood that had been cut or carved by metal tools. Caywood speculated that a member of the Expedition may have whittled on one of those pieces around the campfire one evening, throwing the piece into the fire as he retired to bed. [2] None of the materials from Caywood's excavations underwent any dating process. In reporting his findings, he determined these fire pits to be from the Lewis and Clark Expedition as opposed to campsites of the local Clatsops. He reasoned that the Expedition, with limited resources and supplies, would not have left any scrap materials behind. Caywood also reasoned that "Indians are notoriously untidy" and that the camp had "been thoroughly policed as if by a military group, and all refuse hauled away to a garbage pit." [3] Caywood apparently kept a small box of the excavated materials at Fort Vancouver National Historic Site, which Fort Vancouver Superintendent Frank Hjort sent to western regional archeologist Paul Schumacher in 1961.

|

| Materials collected by Louis Caywood, 1948. (Photos courtesy of Oregon Historical Society, photo negative number 090817) |

In preparation for construction of a concrete foundation for the replica in August 1955, the Astoria Junior Chamber of Commerce (Jaycees) tried to determine the location of the original fort site to help them decide where to place the replica. It was the belief at the time that the fire pits located by Caywood did belong to the original site and the Oregon Historical Society asked that the replica be placed right next to the site. [4] Recent interviews with former members of the Jaycees involved in the replica project resulted in information regarding "remains" and their guess to accurately locate the replica. First, it is believed that the replica was built directly over fire pits, possibly ones that Caywood uncovered, and that the fire pits were used in determining the direction and placement of the replica building. Second, archeologists from an Oregon university may have visited the site to help determine where to build the replica. Third, some Jaycees remember finding charcoal remains while digging trenches for the replica's concrete foundation. Finally, one Jaycee remembers charcoal remains being visible to the south of the OHS marker, where the county road was cut into the ridge. [5] No formal documentation of any of these remains exist.

Paul Schumacher, 1958 and 1961

Public Law 590, which resulted in the Suggested Historical Area Report by John A. Hussey, included archeological investigations by western regional archeologist Paul Schumacher. In December 1956 and April 1957, Schumacher conducted excavations at the site. Schumacher's excavations took place around the replica, inside the parade ground, and towards the canoe landing site.

|

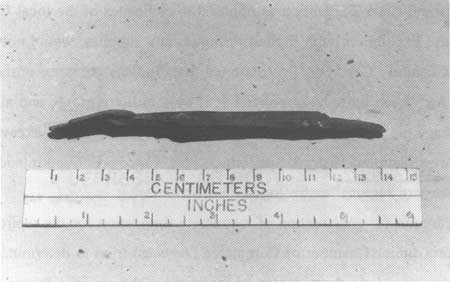

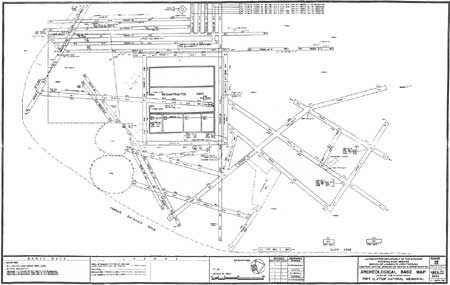

| 1962 Archeological Base Map showing Schumacher and Caywood excavations. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

Through excavation of thirteen trenches, Schumacher uncovered a concentrated series of oval fire pits similar to those found by Caywood. He also uncovered a concentration of 19th century artifacts, which appeared to be the location of the Smith house, built on the site during the mid-1850s. Artifacts uncovered were primarily mid-to-late nineteenth century farm and home settlement items and some American Indian items. [6] Schumacher also uncovered hemlock wood "stakes" which he originally thought to be man made. He later determined that these wood stakes were what local lumbermen referred to as "buckhorns." Buckhorns are the hard, resin-filled cores of tree branches, located where the branch meets the trunk. What he thought were man-made stakes turned out to be a natural phenomenon, and Schumacher speculated that Caywood may have been fooled by this occurrence as he almost was.

Regarding the area containing a concentration of nineteenth century evidence, Schumacher cross-checked his findings with the Clatsop County surveyor, who had a 1905 survey that included the Smith house. The area Schumacher believed to be the Smith house did not correspond with the 1905 surveyor's report. However, excavation trenches dug where the report claimed the house was located revealed nothing. The county surveyor reported to Schumacher that the survey could be off by as much as 100 feet and agreed that he had probably located the Smith house. [7]

|

| Archeological excavations, 1958. (FOCL photo collection) |

Regarding the series of fire pits, two of them were associated with nineteenth century materials. The remaining 10 had similar shape (oval with red clay in the center and charcoal around the top and edges), and an average depth of 0.7 to 2.9 feet. Based on the depth of these pits, Schumacher estimated they were pre-1850 and could possibly have been old enough to be from the Expedition. He also determined that the pits were used over an extended period of time. While the pits were old enough, there was no evidence to indicate if they were created by Clatsops or by a group such as the Expedition. The lack of any substantial evidence around or inside the pits made it possible only to speculate who created them.

Schumacher's investigations also re-examined Caywood's findings. His conclusions were the opposite of Caywood's. While Schumacher agreed that the fire pits could be old enough, he did not agree with Caywood's reasoning in stating they were from the Lewis and Clark Expedition. First, the Clatsops and Chinooks would have had the metal tools available to carve or saw the marked wood pieces. He also disagreed with Caywood's assessment that a lack of evidence was indicative of the Expedition's presence for the reason that they would not have left anything behind. Schumacher felt that there would be some remains of garbage pits, bathroom "sinks," or stockade posts.

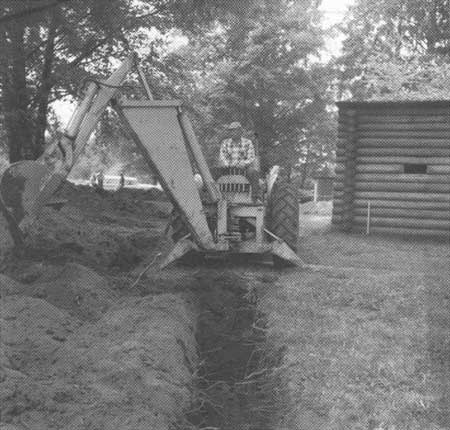

In completing the 1959 Historic Structures Report, Part I, Schumacher recommended further excavation of the subsurface area around the replica grounds prior to any remodeling work. He returned in June 1961 and completed fourteen additional trenches, two feet wide, with the use of a backhoe. Schumacher's findings were reported in the Historic Structures Report, Part II. The excavation concentrated on the area between the fort replica and two prominent cherry trees (trees that are visible in the 1899 photos of the site). More nineteenth century artifacts were uncovered along with additional oval fire pits. However, nothing was uncovered to lead Schumacher to any different conclusions than his 1957 report. He described extensive vegetative root systems under the surface and determined that these subsurface root systems probably destroyed any evidence of the original fort. While Schumacher stated that whenever ground-breaking construction occurred at the site it should be carefully monitored, he determined that no specific excavations for the purpose of locating original fort remains would be necessary.

Since 1961, no specific excavations for the purpose of locating the original fort site have been conducted. All construction and maintenance projects that have required ground disturbance have been reviewed by cultural resource staff for compliance with the National Historic Preservation Act. In 1986, Pacific Northwest Regional Archeologist Jim Thomson surveyed and approved the location of a new sewer system. In 1989, Bryn Thomas of Eastern Washington University, Archeological and Historical Services, Vancouver Office, was contracted by the Park Service to survey the location of the proposed parking lot expansion and visitor center expansion. Thomas conducted surveys of both areas on foot. Subsurface testing was also completed in the proposed areas. Sixteen shovel holes were completed, roughly 30 cm in diameter and 70 cm deep. No archeological materials were uncovered. In 1990, a remote sensing survey of the area was completed in coordination with Oregon State University (OSU). The study, completed by Regional Archeologist Thomson and by James Bell from OSU, revealed seven possible subsurface features, but no definitive results. [8]

What is the probability of there being actual remains? Even if the actual fort was constructed completely above ground, evidence of fireplaces, garbage pits for animal carcasses, or their bathroom sinks should exist. The extensive root systems described by Schumacher could also have revealed evidence of cutting or disturbance caused by the construction of the original fort. Where that evidence may be is the tricky question. Complicating the issue is the evidence possibly left behind from any Clatsop houses built at the site [9], from the houses built by the Shane and Smith families, from the charcoal production of the Stevenson family, from the general traffic of Euro-American settlement, and from the tourist traffic and littering after 1900. The park's reforestation efforts and commitment to revegetation has made possible excavation more complicated.

Adding to speculation about the possible location of the replica has been the discovery through a 1993 Clatsop County survey of a 67-foot error in the 1905 county survey referenced to by Schumacher in 1961. The Smith house discovered by Schumacher in 1961 had been included in an 1856 survey of the area. Oral testimony of Harlan Smith, former resident at the site, states that next to the Smith house was an old, half-buried log which the Smith family believed to be the last remaining timber of the original Fort Clatsop. [10] In 1905, the county surveyor reported that the Smith house had burned down and it was during his survey that the error was recorded, through the placement of a new 1/4 corner marker which was off the correct mark by 67 feet. This error was discovered through a 1993 survey when the 1/4 corner mark from the 1905 survey did not coordinate with the witness points of the 1856 survey. The location of the Smith house is known to be under the start of the Canoe Landing trail. With the known location of the Smith house, the location of the timber reported by Harlan Smith can also be determined. [11]

Collections Management

In connection with the visitor center exhibits, Fort Clatsop National Memorial has developed a small collection of European frontier goods, ethnographic materials, and natural specimens. This collection was started during the search for exhibit materials from 1960 to 1963. Charles Peterson and Burnby Bell contacted several Lewis and Clark historic sites and repositories in a search for items relevant to the Lewis and Clark Expedition. The memorial purchased some nineteenth century woodworking tools and some Northwest Coast ethnographic materials. The memorial also received donations from the local community, including the exhibit canoe, two strands of blue trade beads, and a flintlock pistol. The memorial's collection management statements include the library collection.

For most of the last thirty-five years, the collection pieces not used in the visitor center exhibit cases were stored in two locked museum cabinets in a small storage room. Over the years, the memorial's collection has grown from various donations and purchases. Several items were deaccessioned to Fort Vancouver, including Chinookan burial items. [12] The memorial maintained a Scope of Collections statement as required by NPS policy. According to the 1987 revised Scope of Collections, the memorial shall collect items that "relate directly to events, people, fort construction and occupation associated with the Lewis and Clark Expedition's history and way of life during the 1805-06 winter occupation". [13] The report established guidelines for collecting artifacts, including any available original objects, ethnographic objects, and natural flora and fauna specimens, and for proper storage, care, and access to the collection following NPS policy. The report also established guidelines for continued acquisitions for the park library and archiving of files relevant to the memorial's history. One cultural resource project identified in the new Resource Management Plan is completion of a revised and updated scope of collections statement.

Items in the memorial's collection include: ethnographic materials such as bags, baskets, beads, a canoe, paddles, awls, pestle, metate, and projectile points; Euro-American items such as tools, traps, rifles, an air rifle, the air rifle pump, candle molds, powder horns, and a violin with case; an animal and herb collection includes many species of local plants and beaver and otter pelts.

Under the memorial's 1986 Resources Management Plan, a new environmentally controlled collections facility was listed for cultural resource collection needs. Beginning in 1985, a management assessment was carried out for the memorial collection, which required reviewing and updating the records for the collection. During this process, the collection accessions were entered into a computer cataloging system and all items properly documented. The memorial inventory of collections currently shows approximately 450 items, with approximate values of $150,000 and the library collection worth $50,000. [14]

Part of the design and planning for the new visitor center included an environmentally controlled library and secure collections storage room. During the transition period of the visitor center expansion and the creation of new exhibits, the memorial also achieved necessary treatment and curatorial upgrading through the use of regional curatorial assistance funds. Regional Curator Kent Bush coordinated with memorial staff, primarily seasonal ranger Barbe Minard, on addressing the necessary treatment and storage for the collection. During the visitor center expansion project, artifacts identified for inclusion in the new exhibit cases were sent to Harpers Ferry Center for conservation treatment, along with other items in the collection requiring treatment. The remainder of the collection was stored at the Columbia River Maritime Museum and returned to the memorial in 1991.

Replica Management

Because the fort replica is listed on the National Register and is managed as a historic property, maintenance of the structure falls under the purview of the cultural resources division. When the NPS first received the fort replica, regional and memorial staff conducted research to gain information to remodel the replica for increased accuracy. The result was the Historic Structures Report and Furnishings Plans, Parts I and II. The initial remodeling during the development of the memorial in 1963 resulted in the construction of firepits and a chimney in the captain's quarters; the reconstruction of the main gates; the installation of a second gate; building a sentry box; adding doors; closing the exterior wall gun ports; and opening windows into the parade ground. This work was done under the guidance of the Western Office of Design and Construction historic structures architect Charles S. Pope and Superintendent Peterson. Maintenance foreman Vern Sickler worked extensively building sample chimneys and testing them to determine the proper way to construct fireplaces and chimneys inside the fort. Since the remodeling undertaken by the NPS, the replica has had only general maintenance to replace damaged areas.

|

| Replacement of fort pickets and gates, 1977. (FOCL photo collection) |

Beginning in the mid-1970s, the replica began to show signs of deterioration. Part of the replica's main gate had broken and was temporarily braced by the memorial staff. Superintendent Bob Scott requested an inspection by Pacific Northwest Regional historical architect Laurin Huffman to determine proper repairs and additional maintenance needs. Huffman inspected the replica and completed a report in March 1975. In that report, he cited several problems with rot and deterioration. The main gate needed to be rebuilt due to damaged wood; flashing around the interior chimneys needed to be redone; the exterior chimney needed to be redaubed; the roofing needed to be re-nailed; and cracks along the replica walls creating moisture traps needed to be caulked. Huffman provided ten recommendations for fixing these problems, including directions for rechinking the exterior chimney, rebuilding the main gate, and a treatment process for preserving the wood every two years. In 1977, most of Huffman's recommendations were carried out, and the replica was put on a cultural cyclic maintenance program to prevent further deterioration of the building.

In 1984, the memorial installed new shingles on the fort roof and laid new floor puncheons. Materials for flooring came from Olympic National Park. While the memorial was circulating requests for buying the necessary cedar for shingles, Olympic Superintendent Robert S. Chandler offered for Fort Clatsops use cedar trees that had blown down. The memorial purchased five-foot barn boards for approximately $10,000 for shingles. In 1986, the chimneys in the fort replica were again redaubed. This time, the interior chimneys were remodeled using clay found within the memorial to eliminate the plaster look of the old chimneys. In 1987, the stump in the squad room was replaced with a stump donated from Mt. Rainier National Park.

At the Salt Works site in Seaside, no work has been completed on the replica itself. Various landscaping efforts around the site have taken place. In 1985, a landscape design plan for the site was developed by Renata Niedzwiekca, a historical landscape architect from the regional office. Between 1985 and 1987, memorial management sought to improve the site and implement the landscape plan. The sidewalk was replaced and a new exhibit/bulletin board sign installed. A split-rail fence similar to fencing utilized at the memorial was installed. A native vegetation maintenance program was started for softening edges around the sidewalks and borders. The plan suggested other design projects, to be completed if the opportunity arose, including the development of a trail from the replica to the beach and the proper research and restoration of the replica if repairs became necessary.

In 1991, a new landscape plan was designed by a historical landscape architect from the Pacific Northwest Region, Marsha Tolon. Utilizing some of the same ideas from the 1985 plan, including the future project possibilities, the plan developed new design elements. The split-rail fence was removed and a new cobblestone wall was installed during 1994. This reflects a shift away from design elements used at the memorial to elements that are cohesive with the Salt Works site, which is composed of many different materials and structures in an enclosed city block. The new landscape plan also recommends moving the site bulletin board to a staging area on the Seaside Promenade, which near passes the site, and the installation of new exhibit signs at the staging area next to the replica. The use of natural history signs on a path extension similar to the natural history signs at the memorial is also recommended. The recommendations include the continued maintenance of native vegetation started by the 1985 plan. [15]

Natural Resource Management

During the 19th century, lands now included in the memorial were developed by settlers who built homes, engaged in timber and agricultural production, in tourist transportation to the coast, charcoal production, and possibly some limited clay mining. On the Lewis and Clark River, dikes and levees were constructed. During the 20th century, log rafting on the river and timber harvesting around the area also impacted the natural resources of the memorial. This manipulation of the natural resources of the area greatly altered the landscape from the coastal forest environment that existed at the time of the Expedition's winter encampment. Of the 125 acres acquired by the NPS after 1958, more than half are tidelands. Of the remainder, half contained second-growth trees and vegetation and the other half was open meadow.

Identification of the memorial's natural resources was first sketched out in studies of the park's plants and animals. In 1961, a study titled "Native Plant Materials for Landscaping, Fort Clatsop National Memorial" was completed by student assistant landscape architect R.W. Rhode. This study identified for the memorial what native evergreen trees, deciduous trees, and shrubs could be used for landscaping and screening. In 1969, Margaret McCarter of Clatsop Community College completed "A Guide to the Environmental Study Area, Fort Clatsop National Memorial." In this study, which was updated in 1971, McCarter identified the major plant and animal species on the memorial grounds. Over the last thirty years, several studies identifying plant and animal species at the memorial were completed. Well over 300 different species have been identified in the coastal forest and estuarine habitats of the memorial.

1973 Resource Management Plan

The first ten years of the memorial's management focused on site development and the restoration of the historic scene around the fort replica. These efforts were guided primarily by the park master plan. It was not until 1973 that the park developed its first resource management plan, which outlined five years of natural resource studies. Studies of animal populations, the status of exotic plants, the historical significance of the native vegetation, and a hazardous tree survey and removal plan are examples of the projects listed. Four objectives in resource management at Fort Clatsop were identified: the re-creation of the native plant communities where ecologically feasible; the re-creation of traditional animal populations where ecologically feasible; measuring the human impact on the memorial environment; and fourth, the monitoring of human impacts on the memorial environment. The major resource management emphasis of the plan was the reforestation program.

Reforestation

The restoration of the historic scene through reforestation and planting of native vegetation has significantly altered the memorial's appearance since 1958. Programs carried out at the memorial were aimed at returning the natural environment to the coastal forest environment experienced by the Expedition. This concept, first expressed in 1958, began during site development construction, with plant screening around the fort replica and modern improvements. Primary emphasis was aimed at restoration on the east side of the replica where the previous county road had been. Later, Superintendent Thomson used landscaping and native vegetation to solve the problem with visitor traffic flow bypassing the visitor center.

During the 1970s, reforestation efforts spread to the open field areas targeted in the master plan. In 1973 and 1974, Superintendent Miele arranged for the donation of nursery stock from the Oregon State Forestry Department for reforestation along the county road and the memorial's open field spaces. While Miele's main objective was the restoration of the historic scene, he also saw the measure as cost effective, saving time and money consumed in mowing the surrounding fields. [16] Superintendent Bob Scott continued the reforestation project and over the ten years of his superintendency, 15,000 trees were planted, most of which were planted by Ross Petersen.

By 1980, emphasis shifted from planting to balancing the native vegetation being planted with the second growth vegetation already in existence. A mix of Sitka spruce, western hemlock, western red cedar, and Douglas fir composed the forests seen by Lewis and Clark. The alterations to the landscape over 150 years also shifted the balance of species in the area. Specifically, red alder had spread into areas where other native species had been removed. As the young trees being planted grew, red alder was targeted for thinning and removal to promote the growth of the selected native species. A gradual system of thinning and planting developed that from 1980 and 1986 removed between one-half and three and a half acres of red alder per year. [17] The cut wood was then utilized in the fort replica fireplaces and in the employee residence wood stoves. In 1985, there was enough of a surplus that wood was sold to the public. The following year, surplus firewood was given to Fort Vancouver for use in the bakery and blacksmith shop.

In 1984, the Resources Management Plan and needs were revised, stating the memorial's main objective in natural resources as the continued maintenance of the native vegetation and planting program. [18] Through deliberate maintenance, the memorial would be able to foster a diversity of species and the creation of shelter for elk and deer populations. Another plan revision was completed in 1986. While this revision did not change the objective for maintaining the native planting program, it added two additional natural resource management goals. The planting program was so successful that vistas between the fort and the river needed to be thinned to keep river views open. Second, pest management needed to be addressed to control any threats to the native plants. [19]

Resource Studies

In 1987, the Pacific Northwest Regional Office, Cultural Resource Division, developed a forest landscape plan for the memorial. The plan identified small landscaping features to improve the interpretive features of the vegetation program. Removal of grass in front of the replica, selective removal or limbing to open up the view of the fort and wayside exhibits, and less defined trail edges were some of the recommendations. This plan mainly addressed the interpretive value of the native vegetation in the historic scene.

In 1989, Superintendent Frank Walker contracted with Dr. James Agee of the College of Forest Resources, University of Washington, Cooperative Park Studies Unit, to complete a forest landscape study. This study was designed to assess the developing forest on the memorial property and design maintenance guidelines for maintaining the health and landscape appeal of the forest. It also was intended to answer three fundamental questions: what was the goal in re-creating the 1805 forest, what features would that represent, and how would it be managed when it was reached?20] This plan took the memorial further away from replanting efforts and towards the goal of maintaining a healthy coastal forest environment.

Agee's study was designed to give management ideas for the future maintenance of the memorial forest. The plan acknowledged that the forest of 1805-1806 was an evolving forest and that no one set instance in time could be re-created and represented as such. Agee identified historic native species of the Fort Clatsop area, describing it as a part of the Sitka spruce zone. Agee considered the natural and human agents which would have shaped the pre-settlement forests of the area. Wind, fire, and human uses would have continually shaped the forests of the Fort Clatsop area. To help guide the memorial, Agee listed proper thinning recommendations to stimulate a healthy growth and undergrowth, for protection against pests, and protection against wind disturbance.

Resource Management In The Future

Under Superintendent Cynthia Orlando, management emphasis was placed on the development of a resource management program area at the memorial. The first step came with funding and hiring a resource management specialist. The goal of the resource program is to identify the current needs of park resources and to establish a formal program and goals to meet those needs. The creation of a formal resource management program will allow the memorial to meet resource management responsibilities and request resource management funding for those projects.

In 1994, the memorial completed a new Resources Management Plan document outlining future projects at the memorial. The plan is intended to be "a long-range planning document which identifies the park's natural and cultural resources, outlines the various known resource information deficiencies, issues and concerns, and provides direction and strategies on how to address them. Fiscal and human resource needs are also identified." [21] The plan currently contains 81 project statements, incorporating all areas of resource management needs.

Also in 1994, the memorial and the water resources division of the NPS completed the "Fort Clatsop National Memorial: Water Resources Scoping Report." This report examines the memorial's wetland and estuary habitats, identifying significant water resources and issues at the memorial. Five project statements were developed "to enhance water resources management activities within Fort Clatsop National Memorial". [22] The project statements are for the completion of a topographic/subdrainage map, a complete wetlands inventory, a wetlands restoration feasibility study, implementation of a water quality monitoring system, and a biotic inventory for water resources. The scoping report and the inclusion of its project statements in the new Resources Management Plan reflects a recent recognition and emphasis on the identification and assessment of the memorial's significant and valuable water and wetland resources.

The primary emphasis of resource management program at the memorial is the integration of natural and cultural resource management and resource protection according to federal legislation and NPS guidelines. Through active planning and needs assessment, the memorial hopes to identify resource management needs and programming which will not only sustain the memorial's resources, but also protect them against current and future incompatible adjacent land use.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

lewi/adhi/chap7.htm

Last Updated: 20-Jan-2004