|

NAVAJO

The Excavation and Repair of Betatakin |

|

BETATAKIN ARTIFACTS IN THE NATIONAL MUSEUM

The cultural plane attained by any primitive people is determinable in part by their habitations; to an even greater degree, by articles daily employed in and about those habitations. This truism holds not only for Indian tribes living in the United States a generation ago but also for those that passed on before the origin of what we commonly call the "history" of our country, beginning with the voyages of Eric the Red and Columbus.

It would be altogether unjust to the prehistoric builders of Betatakin, therefore, were I to attempt portrayal of their arts and industries from the few, miscellaneous artifacts recovered during the course of our work in 1917. These were all casual finds, disclosed as we cleared away the vast accumulation of detritus and household rubbish with which the ruin was blanketed. Alone, these chance objects tell an incomplete story. But they may add something to that history of the village which is yet to be written; hence, it seems desirable briefly to list those minor Betatakin antiquities now preserved in the national collections.14 National Museum catalogue numbers accompany those specimens mentioned but not illustrated; the list on page 75 gives the numbers and dimensions of those shown by plate and text figure.

14Every specimen regarded as reasonably secure from the habitual curio collector was left at the ruin.

OBJECTS OF STONE

Metate (pl. 31, 1).—The only milling stone brought away was last used for pulverizing yellow ocher; a rubbed area on its under side is smeared with red paint. Of fine-grained sandstone, the specimen has a grinding surface transversely plane but longitudinally concave, being worn in the middle to a depth of five-eighths of an inch.

To judge wholly from want of contrary statements in my field notes, the characteristic Betatakin metate is relatively thin, rather carefully shaped by pecking with hammerstones, and rarely, if ever, deeply troughed.

Manos, or mullers (pl. 31, 2-5) are the hand stones with which maize and other foodstuffs were ground on metates. Among the 30 manos (312207-27) in our collection, certain dissimilarities of shape and size are obvious. This variation is owing to the structure of the sandstone, volcanic breccia; and vesicular quartzite from which all are made and; perhaps in equal degree; to personal differences in method of use. Eight of the 30 appear to be reworked and reused mano fragments; they vary in length from 4-3/4 to 6-3/4 inches (0.120 to 0.171 m.). The remaining 22 average 4-1/4 inches (0.107 m.) in width by 10-1/4 inches (0.260 m.) in length. Six of these are provided with shallow finger grips on the longer sides, while three only, and four of the shorter ones, show wear on both sides. Four of the series, all long mullers, are slightly wedge-shaped in cross section; three, including a reworked fragment, exhibit a convexity due to wear on a narrow, shallowly troughed milling stone. On the flat-faced metates of Betatakin, flat-faced manos naturally were employed.

Rubbing stones, supposedly for smoothing newly surfaced floors, walls, etc., bear a close relationship to the manos and might well have substituted for them upon occasion. Our three specimens of this type (pl. 32, 7-9) are all of sandstone, somewhat oval, carefully shaped at the periphery, rubbed on both faces. Water-worn cobbles frequently were carried long distances by Pueblo peoples living in a region of sand and sandstone. From Betatakin we brought two such cobbles (312231), both of which show slight use as smoothers. One is of quartzite; the other, diorite.

Six small pebbles (312232), worn smooth by stream action, were used to polish the thin clay slip with which earthen vessels were surfaced. Such pebbles were the handy tools of Pueblo potters in middle and late prehistoric times.

Two still smaller pebbles of white flint (312310) are flattened on one or more sides. Similar specimens have been found heretofore in a medicine man's outfit.

Hammerstones.—Any hard, tough stone served as a hammer. Of the three in our series (312233), two are quartzite cobbles polished by blown sand before human use; the third and largest (pl. 32, 6) is of chert.

Mauls.—Our two mauls are each provided with an encircling groove for attachment of the customary withe handle. The larger, of heavy sandstone, is flattish and irregular, but evidences considerable work with the pecking hammer. (Pl. 32, 4.) In marked contrast, the second is merely an elongate basalt cobble (312240), grooved about the middle and probably used but once or twice.

A much smaller and more globular specimen (312241), of vesicular quartzite,15 while maullike in shape may have been intended as a weapon. There can be little doubt, however, that the one shown in Plate 32, 5, was designed as a club head, for it was carefully pecked then smoothed with a sandstone rasp. Its pointed ends, slightly battered on other rocks, illustrate the readiness with which almost any Pueblo implement was pressed into service for which it was not primarily intended.

15A seemingly porous material containing variecolored stone pellets and described by the late Dr. George P. Merrill. head curator, Department of Geology, U. S. National Museum, as "a very interesting and peculiar type of quartzite."

Stone axes (pl. 32, 1-3).—The four recovered, all of diorite, are relatively crude, like most axes from ruins throughout the San Juan drainage. The smallest of those illustrated has a secondary groove just below the principal one.

Celt.—The well-known celt or tcamahia of the San Juan Basin is represented by a single, fragmentary specimen of reddish argillaceous chert (312243). Its handle is mostly missing, but on the remaining portion a perceptible difference in coloration indicates the former presence of a covering or wrapping. The blade had been broken, rechipped, and the sharp edges slightly rubbed.

Chipped implements.—Of the six flint points at hand (312312), two are arrowheads. The smaller of these, triangular in shape, is three-quarters of an inch long; the other, notched and slightly barbed, measures 1-3/4 inches. The other four specimens may be regarded as knives. Their bases are square or nearly so, and to two of them some adhesive, probably pitch, still cleaves. The largest of the lot, its tip missing, measures 1 by 2-1/2 inches (0.025 by 0.063 m.); its sides and edges have been slightly smoothed by rubbing. The wooden knife handle illustrated by Figure 5 was collected at Betatakin by Professor Cummings in 1909 and added to the national collections through exchange with the University of Utah.

|

| FIGURE 5.—WOODEN KNIFE HANDLE |

A small fragment of a red jasper flake (312313) had been chipped along each side, for use in cutting or scraping.

Stone pellet.—A rounded stone ball (312309), five eighths of an inch in diameter and blackened by fire, served an unknown purpose.

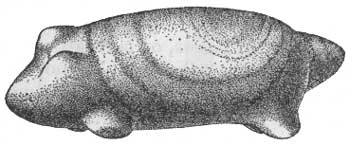

Effigy.—No one may say what animal is represented by the little stone effigy shown in Figure 6. Its front legs, mere knobs at best, have been broken and subsequently rounded.

|

| FIGURE 6.—STONE EFFIGY |

Turquoise.—The fragment of a small, semilunate bead, V-drilled on the flatter side, is the only piece of turquoise collected (312311).

Pendant.—The only undoubted ornament we recovered is a thin disk of red clay stone (312304), drilled at one edge for suspension and in the middle for diversion.

Lignite ornament (fig. 7).—Through a ridge across the middle back, two V-drillings provided means of attachment. On one edge are four vertical and parallel incised lines. The material is lignitized wood, highly resinous.

|

| FIGURE 7.—LIGNITE BUTTON |

OBJECTS OF WOOD

For working wood, the inhabitants of Betatakin had only flakes and chipped knives of flint; they used sandstone for rasping and smoothing.

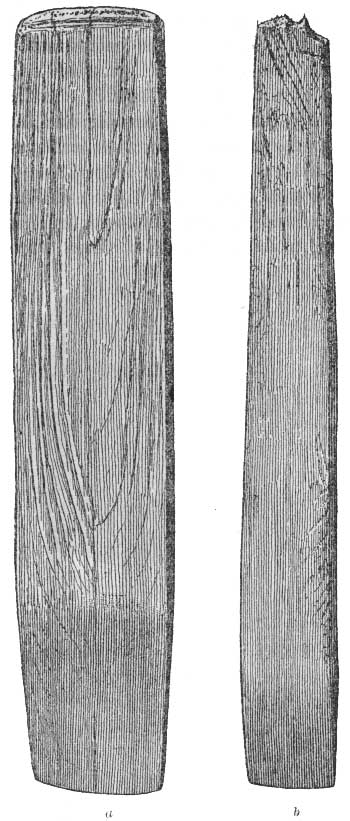

Board (pl. 33, 1).—The specimen illustrated is an oak board, carefully finished but subsequently burned. Through one corner is a nearly vertical, drilled hole; on the same side and at approximately one-third the total length is a similar hole, bored at an angle of 55°. The two fragments which compose this specimen were found widely separated, the larger on the surface; the smaller, buried in the sand above room 55. Hence the difference in coloration seen on the original.

A small, charred fragment of a like board, of cottonwood, is also drilled through one corner; the flatter side is deeply scored by cutting tools (312346).

Billets (pl. 33, 2-4).—Three cottonwood billets, or lapboards, and fragments of two others (312343) are in the collection. Two of the five still possess the original convex curve of the tree trunk, although slightly modified; all exhibit on their flat sides and rounded edges the marks of cutting and scraping implements or the pricks of some sharp-pointed tool. The longest of the three illustrated was made from a cottonwood root; all the others are from sections of the stem.

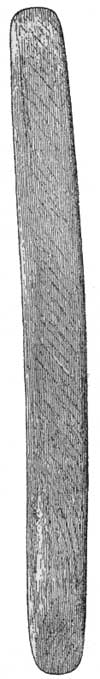

Digging sticks (pl. 34, 4-7).—Nine reused fragments of oak digging implements are all we found. For fuller understanding of these essential tools of primitive agriculture, reference should be made to Kidder and Guernsey (1919, p. 119) and other authorities.

In addition there is the problematical specimen shown in Plate 34, 1. Doubt hangs upon this latter from the fact that its pointed end is rounded and blunted, not flattened and sharpened as is always the case with serviceable digging sticks. Conjecture might identify this as the oak staff or cane of some venerable villager.

Staves.—What seems unquestionably a walking stick is that illustrated in Plate 34, 2. Except for smoothing a few knots and trimming the two ends, no specialization is evident. The stick is cottonwood; its grip is worn and the lesser end rounded and abraded. Fragments of a like staff (312327) show a hole drilled transversely through the handle and, at the opposite extreme, the asymmetric wear such as one frequently notes on canes used by elders.

A third cottonwood staff (pl. 34, 3; fig. 8) differs from those just considered in that its lower end is circled by 14 incised grooves. Some of these were made before, others after, an 11-inch splinter was cut away and its place gouged out. Except that the incisures circle its smaller end, this particular specimen might be likened to the so-called "ceremonial staves" occasionally found in Pueblo ruins.

|

| FIGURE 8.—CARVED END OF COTTONWOOD STAFF |

Bows and arrows.—In the collection are three fragments of two self bows, each made of red cedar (312331). The fragments are burned and blunted from use about a fireplace, but they show careful workmanship and a grip that measures 1-1/4 inches wide by 13/16 inch in thickness. Figure 9 shows the severed end of a third bow.

|

| FIGURE 9.—DETACHED BOW END |

Four wooden foreshafts for reed arrows (312360) average 8-1/2 inches (0.215 m.) long; they are all shouldered and the two unbroken have plain, sharpened points, as does that from a shallow cave near Betatakin. (Fig. 10.)

|

| FIGURE 10.—ARROW FORESHAFT |

Fire-making tools (pl. 35, 5, 9).—Three drills, two of them broken, and fragments of two cottonwood sticks with charred sockets identifying them as hearths, constitute all the fire-making apparatus we found in Betatakin.

Awls (pl. 36, 5-11).—The collection includes nine wooden awls measuring from 6-3/4 to 10-3/8 inches (0.171-0.263 m.) in length. Their butts are rounded or flattened and square cut; none is spatulate. While two or three appear to be of red cedar a harder, more durable wood was preferred. Two smaller examples (fig. 11) are probably to be classed in this group.

|

| FIGURE 11.—SMALL WOODEN AWLS |

Toothed implements (pl. 37, 1-5.)—Our five examples are all of red cedar. Two of them (2-3) have spatulate or knifelike butts; 1, cut from a splinter, is less carefully finished. It will be noticed that the number of teeth varies. The split and reworked edge of 2 indicates at least a former fifth tine, while the two fragmentary specimens apparently had 10 or more teeth each, and these were closer together, longer, and more rounded than in the others illustrated.

Knives.—Red cedar, of course, will not take an edge capable of cutting hides or equally resistant substances. But the two spatulate objects shown in Figure 12 have knifelike edges, and these are stained with what may be blood. Kidder and Guernsey (1919, p. 120) have called such instruments "skinning knives" under the quite logical assumption that they might have served in flaying animals.

|

| FIGURE 12.—SPATULATE IMPLEMENTS OF WOOD |

The unfinished specimen represented by Figure 13 is included here only because its two ends are ground to near-cutting edges. Both sides are scored by the coarse sandstone rasp employed in the final shaping process.

|

| FIGURE 13.—SPATULATE WOODEN IMPLEMENT, UNFINISHED |

Paho (pl. 35, 1).—This cottonwood cylinder bears such a close resemblance to similar objects associated with certain Hopi rituals as seemingly to justify the designation. Its upper end is twice grooved, but displays no evidence of wear owing to cord attachments. A slight depression at this extremity is quite fortuitous, but in the base is a central, drilled concavity five-sixteenths of an inch in diameter by three-sixteenths inch deep.

Flute (?).—Large wooden flutes were employed by prehistoric as by historic Pueblos. But all modern flutes examined by the writer have been made in two parts, each gouged out in perfect agreement with the other and the two fitted together with exactness. The fragmentary specimen in hand (pl. 35, 3; fig. 14) must have been produced by like means, for its inner surface is finished with such nicety; is polished and blackened so uniformly as to preclude use of any method of drilling known from the Southwest. Both edges are split. There remains no evidence of drilled holes; no trace of wrappings. Yet the fragment is almost certainly part of a large flute. The 14 external grooves were incised with flint flakes or knives.

|

| FIGURE 14. — SECTION OF WOODEN FLUTE (?) |

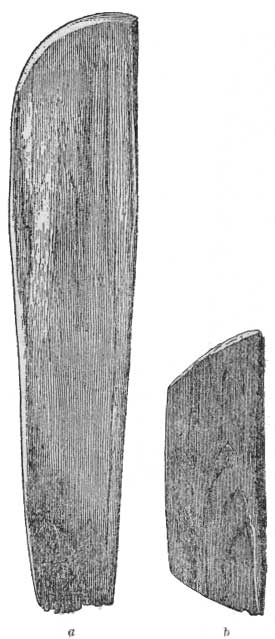

Scrapers (fig. 15, a-b).—The usual number of pine and cedar splinters employed in smoothing and scraping operations is in the collection.

|

| FIGURE 15.—WOODEN SCRAPERS |

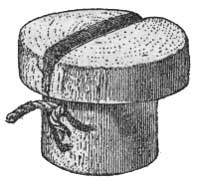

Mask attachment (?)—A stopper-like object of cottonwood (fig. 16) is one of several specimens whose original function may only be surmised. Two cotton strings, projecting from a hole drilled through its lesser diameter, appear to have crossed the larger in the groove indicated.

|

| FIGURE 16.—WOODEN OBJECT |

Painted stick.—A cylindrical piece of wood, probably willow, 7/16-inch (0.011 m.) in diameter by 1-3/4 inches (0.044 m.) long, covered with thick, dark green paint (312299).

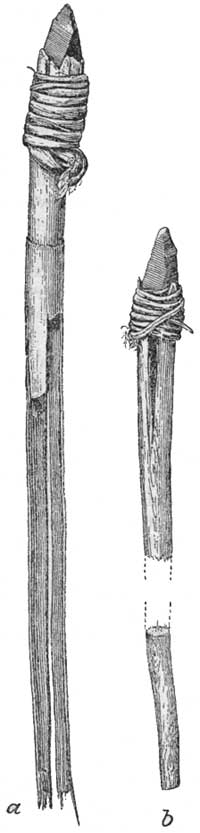

Drill.—It is incredible that the crude drill shown in Plate 36, 1 and Figure 17, b was the tool of a skilled artisan. Its rudely chipped, chert point is set in the split end of a greasewood shaft and loosely bound with a shred of yucca leaf. A second drill, comparable in crudeness but less worn, is mounted in a reed shaft. (Fig. 17, a.)

|

| FIGURE 17.—DRILLS |

Spindle shafts and whorls (pl. 36, 2-4; 12-16).—Spindle shafts are invariably made of some hardwood that takes and holds a smooth, even finish. Our longest (312363), a fragment, measures 1/4-inch in diameter by 23-3/8 inches (0.006 by 0.59 m.). Such slender, pointed shafts as 2 seem altogether too fragile for spindles.

Six whorls, mostly cottonwood, vary in diameter from 1-1/2 (0.038 m.) to 2 inches (0.050 m.); in thickness, from 5/8 (0.015 m.) to 1-5/16 inches (0.033 m.). The finest (13) is convex on one side; flat and centrally cupped on the other. One fragmentary specimen (312287) is convex on both sides. Two (15-16) are of mountain-sheep horn, as is the squared block, a doubtful whorl, shown in Plate 36, 17.

Miscellaneous wooden objects.—We have the usual proportion of peeled and unpeeled sticks with cut ends; fragments severed from finished implements; slender, smoothed twigs with one pointed end; worked objects of unknown use (pl. 35, 6-8); splinters and twigs with sinew or cord wrappings (pls. 35, 2; 37, 6-9).

The oak stick pictured in Plate 35, 4 has been split to permit insertion of a scrap of cotton cloth; a wrapping of some sort formerly circled the stick and covered this fragment. The willow rings shown in Plate 34, 8-9 may be regarded as hastily improvised potrests. A charred oak stem (312328) with four branches, the two unbroken having rounded tips, could have served as a vertical support for hanging various articles.

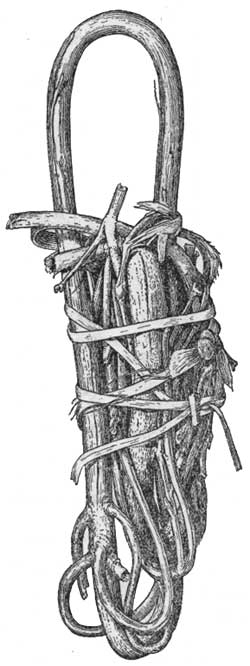

Figure 18 shows a not uncommon type of loom anchor—an oak branch, knotted and tied with yucca, and buried so that the loop lay just below the floor level.

|

| FIGURE 18.—LOOM ANCHOR |

OBJECTS OF BONE

Awls (pl. 38, 1-8).—Of the 11 awls in our collection, only one (1) is of bird bone, and that the tibiotarsus of a turkey. The longest (2), with its specialized point, and the two rounded specimens (7-8), are worthy of note; the others are mere splinters and cut sections of mammal bones, shaped by abrasion on sandstone. Figure 19 illustrates a needle whose drilled eye is so small as to take but a single yucca fiber.

|

| FIGURE 19.—BONE NEEDLE |

Fleshers.—The three typical examples in Plate 38, 9-11, are all of deer bone, the larger two from the femur.

Miscellaneous bones.—From almost every Pueblo ruin come diverse bones and fragments, many of which show at least some slight evidence of modification by human agencies. Only two such pieces were retained from the Betatakin excavations: (1) The humerus of a turkey from which both condyles were removed (312377), and (2) the cannon bone of a deer (312381), partially split by sawing on each side with flint tools. In addition, there is an unworked fragment of mountain-sheep horn (312382). A drilled block and two spindle whorls of horn were noted in a preceding paragraph.

OBJECTS OF VEGETAL ORIGIN

Brushes (pl. 39, 1-3).—The three specimens illustrated are composed of what appears to be cedar bark, completely charred (1), trimmed yucca leaves (2), and wire grass (3). Each is tied with a shred of yucca leaf. Brushes were employed in combing one's hair and in sweeping floors and, often enough, the two ends of a single specimen served these two entirely unlike purposes.

Cordage.—As is well known, most cliff-dweller cord was made of yucca fiber, that handy material so generously distributed throughout the greater part of the Southwest. The bundles figured in Plate 39, 4, 5, are of an unidentified species of apocynum and yucca, respectively. A second hank of yucca cord is embedded in a bit of adobe flooring, marked by the imprints of willow (312257). In addition, we have the usual number of scraps of feather-wrapped yucca cord; a tasseled fragment, square braided, of eight 2-ply cotton strands (312272); several cord fragments made from human hair (312275); a bit consisting of two strands of hair twined with one of yucca fiber (312274); and several knotted scraps of twisted buffalo hair (312281).16 Bundles of human hair, tied with yucca shreds and perhaps intended for use in cord manufacture, or for weaving bags and other fabrics, are also in the collection.

16Kidder and Guernsey (1919, p. 118) note the finding of a scrap of buffalo hide, with the hair still on, in their ruin 7 and point out the possibility of its having been brought in by Navajos. Biologists have not yet included the Kayenta district in the known, former range of the mountain buffalo.

Mats.—From the Betatakin cave débris came a small section of cedar bark matting, bound with a simple over-and-under lacing of yucca leaf shreds (312321); a similar fragment composed wholly of yucca leaves (312409) and several pieces of a larger mat, twill woven of rushes (312395).

Cloth (pl. 39, 6-9).—Bits of cotton fabrics, often patched and repatched, are present in nearly every cliff-dwelling rubbish heap. Most of these rags show a plain checkerboard weave, although their component threads may vary in size and compactness. Our rag series includes four specimens of twilled work (312259), two of which appear to be fragments of headbands, and a cotton tassel whose cord, seven-sixteenths inch in diameter, consists of a core of cloth strips inclosed by a covering in which three parallel strands were braided as one.

Our only example of twined textile is woven of human hair. A single specimen of coiled work without foundation has what appears to be buffalo hair twisted in with some species of apocynum fiber.17

17A similar scrap (303262) in the Betatakin series obtained through exchange with the University of Utah includes both cotton and apocynum strings in which is twisted whitish mammal hair, as yet unidentified, that may he either deer or mountain sheep, and also the brown hair of some undetermined animal.

Sandals.—Two types of weaving, twilled and wickerwork, are represented in the 11 sandals or sandal fragments we collected at Betatakin. Of the former, there are but two examples, both made from narrow yucca leaves. (Pl. 40, 1, 3.) The larger is the finer and more tightly woven; its component elements were plaited over-two under-two until the edge was reached, when each strand was tightened, drawn forward under-four, and reintroduced from the lower side, thus creating a slightly thicker, rounded selvage. As the weaving progressed from toe to heel, leaf ends were brought out on the sole, there to be clipped and later frayed through wear into a fibrous pad. (Pl. 40, 2.) To complete the weaving, each strand was tied in a single knot under the heel.

The smaller sandal, woven in the same technique, is a bit cruder and might well be the work of an adolescent. On the border, each leaf was brought forward under-two and reintroduced. The toe ends were mostly drawn out on top, intertwined, and left to form a knotty pad. In finishing the heel, one strand was brought squarely across and the others looped about it, half above and half below, after which their ends were clipped. As a final touch, two strips, tied together on the middle left edge, were laced back and forth across the sandal, one to end at the toe; the other at the heel.

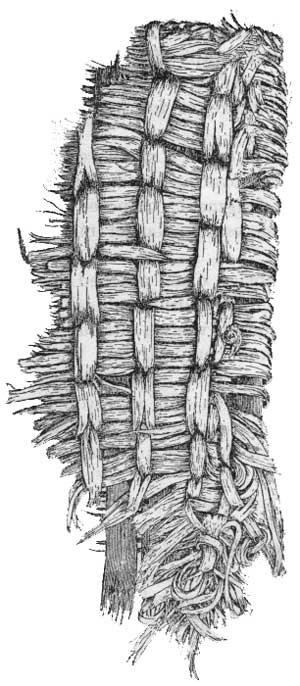

Although our wickerwork sandals (pl. 41, 1-3) present an entirely different appearance, one from the other, the method of their manufacture was much the same. All are made of yucca. Coarse leaves were looped and tied to form four warp strands; back and forth across these, over one and under the next, the weft element was woven. This might be narrow yucca leaves (2, 3) or a sort of bast of finely shredded leaves (1). Apparently to bind these weft strands together, strips of the same material were sometimes laced through longitudinally between the warps, as in 3. The extreme to which such stitching can go is illustrated by Figure 20.

|

| FIGURE 20—WICKERWORK SANDAL WITH SECONDARY STITCHING |

One fragment in the lot is woven of yucca bast over four warp strands of coarse yucca cord.18

18For an excellent analysis of wickerwork and twilled technique in sandal weaving, see Kidder—Guernsey, 1919, pp. 101-107.

Basketry.—In our 1917 Betatakin collection, basketry is represented by the two specimens figured in Plate 42 and by several fragments (312394) of similar vessels. The ring basket (1), a very common sort of receptacle among cliff dwellers of the Kayenta district, is woven of trimmed yucca leaves in simple twilled pattern; that is, each weft element alternately goes over-two, then under-two warp elements. Construction began at the center and the two primary strands, at right angles to each other, tend naturally to quarter the fabric. Continuing outward from the middle along these two strands, every fourth weft element extends over-three thus to produce the concentric diamond pattern faintly discernible in the illustration. At the rim, the component strands were gathered in pairs and clipped. Each alternate pair was brought over from the outside and tied with its neighbor just below the ring, by thin twined strips of yucca. In this particular specimen, the unpeeled willow forming the hoop had been broken and subsequently repaired with a similar withe, lashed on with more shreds of that most useful plant, the yucca.

As to our coiled specimen (pl. 42, 2) and fragments, little need be said other than that each was woven in the manner described by Kidder and Guernsey19 as "two rod and bundle." In this style, each coil consists of two tiny willow rods, placed side by side with a bundle of fibrous material above and between them. Coiling progressed as the sewing splints were drawn through the middle of the bundle and over the three elements (two rods and bundle) of the coil next above.

191919, p. 110.

In the small series of Betatakin artifacts collected by Professor Cummings and obtained by the United States National Museum through exchange with the University of Utah, are two fragmentary yucca ring baskets of twilled weave. (Pl. 43.) One (1) is woven over-three, under-three, with each sixth element on the quartering strands over-five; the other (2), over-two under-two, as described above. The fragment of a larger ring basket, approximately 15 inches (0.381 m.) in diameter (303269), and part of a coiled specimen, 6-1/2 inches (0.165 m.) in diameter, woven on a single-rod and welt foundation (303270), will also be found in this collection.

Cradles.—During the course of our clearing operations we found a fragment of what might have been a cradle (312396). Uncertainty lies in the fact that the specimen, when in use, obviously was broader than known cradles from the Kayenta district; from the further fact that the reed backing follows the curve of the hoop without apparent interruption. This hoop is an unpeeled oak withe; the reeds were added one at a time, each being bent around the oak frame and lashed with a pair of twined yucca strands.

Plates 44 and 45 show the front and back of a fragmentary cradle of superior construction, exhumed at Betatakin by Professor Cummings in 1909. A peeled oak twig, partly split to aid in bending it to the shape desired, forms the frame. To the under side of this, selected reeds were bound by a single yucca-leaf strand in running coiled stitch.20 Such lashing, and a cornhusk pad that covered it and the reed ends, was subsequently inclosed by twilled weaving (over-three, under-three) of unidentified basketry material. The original dimensions of this exceptional specimen were approximately 12 by 24 inches (0.304 by 0.609 m.).

20The thread crosses the twig, goes down and encompasses two reeds beneath; thence back over the twig and down again to inclose one of the same two reeds and the next beyond; thence back over the twig, and so on.

Two sets of reeds, at right angles to each other, compose the body of the cradle. First to be attached was the transverse series above mentioned, of which 72 elements now remain. Upon these, 26 longitudinal rods were bound in pleasing pattern with two-ply cords of human hair. Close inspection of the illustrations will show the running coiled stitch that binds the outermost stems of the upper set to each one in the lower. The lowermost and each twenty-fifth cross reed above (pl. 45) is fastened to individual rods of the opposite series by a wrapped stitch in which a single cord twines about the horizontal member as it crosses, successively, those placed lengthwise. This method of attachment resulted in a sequence of three rectangles each of which is bisected diagonally by coiled stitching.

It is to be noted that only 2-ply human hair cord was utilized as a sewing element in binding the two sets of reeds which compose the body of the fragmentary cradle before us. But a shred of yucca leaf, looped over several lateral stems, served subsequently for minor repair.

Foodstuffs.—Maize has formed the staple food crop of Pueblo peoples since Basket Maker times. Innumerable cobs appeared in the household rubbish with which Betatakin was terraced; those few we salvaged (312266) average 6-1/2 inches (0.165 m.) and are among the longest. We found also three small red beans (Phaseolus vulgaris—No. 312268)21 and various squash stems, seeds, and fragments of rind (Cucurbita pepo—Nos. 312261, 3, 5). Pinyon nuts, the seeds of desert grasses, and edible roots, such as a species of wild potato that grows abundantly in canyons of the Kayenta district, contributed, each in its proper season, to the products of cultivated gardens. No useful list of the diverse game animals killed for food can be compiled from the handful of worked bones retained.

21This and the following identifications were made by Mr. D. N. Shoemaker, of the Bureau of Plant Industry, U. S. Department of Agriculture.

Figure 21 shows two severed fragments of a gourd vessel. It is understood that to-day, as in prehistoric times, young wild gourds are still eaten by several Southwestern tribes.

|

| FIGURE 21.—FRAGMENT OF GOURD VESSEL, CUT IN TWO |

POTTERY

The half dozen specimens we recovered afford no adequate conception of the variety of earthenware vessels employed in Betatakin nor of the skill that went into their making. From shards gathered on débris heaps, something could be written of local technique; of different wares and their characteristic types of paste, surface treatment and decoration. But this has already been done by those diligent, painstaking observers, Kidder and Guernsey.22

22See Kidder-Guernsey, 1919, pp. 129-143; Kidder, 1924, pp. 68-74.

Let us briefly consider the few pieces in hand since they are the only ones in the National Museum collections known to have come from Betatakin.23 Our two whole vessels (pl. 46, 1, 3) are both polychrome. The flat-topped colander (1) was finished with a red slip, except for a narrow, cream-colored band around the shoulder; on this smooth red surface black geometric decorations were painted and outlined in white. Ornamentation is confined to the body and to the slightly depressed rim. The flat bottom is perforated by 41 holes, one-eighth inch in diameter, punched through from the outside. This is the strainer previously noted as having been found in the hole pecked in the stone floor of room 121.

23Accesion 52301, transferred from the Bureau of American Ethnology, includes a number of vessels perhaps erroneously credited to Betatakin by the collector, Dr. J. W Fewkes. Certainly they display none of the distinguishing features of Kayenta, or even proto-Kayenta, Wares. In the report on his preliminary visit, Fewkes implies (1911, p. 26) that fragments only were gathered at this site.

To the gray paste of the small handled jar (3), a brown paint was applied from the rim to just below the maximum diameter; over this, black designs were drawn and bordered with white. The larger jar (5) likewise was rubbed to a near-polish with waterworn pebbles then ornamented directly with broad, brown bands, outlined with a darker paint that may be regarded as an impure black. The same pigment was employed in tracing the coarse, parallel lines that occupy the interspaces. Bits of wood, gourd rind, and fragments of broken pottery (fig. 22) were employed as scrapers in the manufacture of earthenware vessels.

|

| FIGURE 22—SHARD POTTERY SCRAPER |

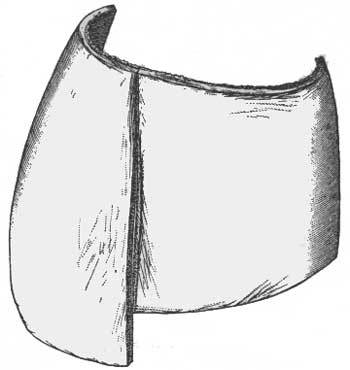

Of the two bowls, both restored, the larger (6) was first coated inside and out with a thin red slip, polished and then decorated with a coarsely hachured, convoluted design in black. Ornamentation is limited to its inner surface. The smaller specimen (2) has an out-flaring rim and a single, horizontally placed loop-handle—two characteristic features of bowls belonging to the principal Kayenta culture. But this particular vessel bears no decoration whatsoever. Its exterior was roughly smoothed; its inner surface was covered with a cream-colored slip and polished. Variation in Betatakin bowl rims is shown by Figure 23, drawn from fragments in our shard collection.

|

| FIGURE 23.—RIM TYPES OF BETATAKIN BOWLS |

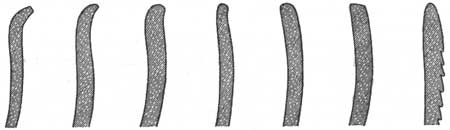

In this same series are segments of four shallow, platelike vessels with perforated edges (fig. 24), a type limited in distribution, as far as I am aware, to the Kayenta district, and to Jadito Valley, southeast of the modern Hopi villages. Fewkes24 illustrates a restored specimen, 5-1/4 inches (0.133 m.) in diameter, from the Marsh Pass region; Kidder and Guernsey25 observed fragments of similar dishes on ruins in the same locality and were so fortunate as to recover half of a 13-inch (0.330 m.) plate, threaded with strips of yucca, at Sunflower House, on the south margin of Skeleton Mesa some 2 miles below the mouth of Segi Canyon. Both their pronounced shallowness and their marginal perforations attract attention to these unusual vessels. What purpose they originally served remains undetermined. Hough appears to be the only one who has ventured an opinion. After noting the occurrence of fragments in large numbers at Kawaiokuh and their relative infrequence at Kokopnyama, protohistoric Hopi villages in Jadito Valley, he conjectures the use of such plates as "revolving rests for ware during the process of manufacture."26

241911, pl. 15, b.

251919, p. 143.

26See Walter Hough: Archaeological Field work in Northeastern Arizona. The Museum-Gates Expedition of 1901. U. S. National Museum, 1901, An. Rept., pp. 337 and 343. Washington, 1903.

|

| FIGURE 24.—RIM FRAGMENTS OF POTTERY PLATES |

In other words, a rotative disk that could be turned as the formative vessel it supported took shape—nearest aboriginal approach in the New World to the potter's wheel.

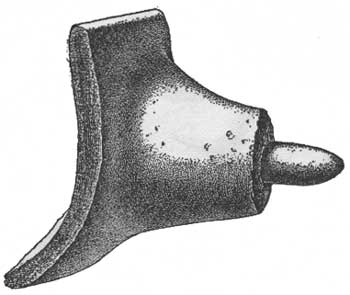

Like the two jars previously mentioned, the broken ladle shown in Plate 46, 4 received no surface slip. It bears no trace of ornamentation either within the bowl or on its flat, solid handle. In prehistoric times, as to-day, Pueblo potters habitually modeled a ladle handle separately and frequently attached it by inserting one end through a hole punched in the still plastic clay of the bowl, the union then being smoothed over and completely obliterated. This union, in the case of tubular handles, was occasionally strengthened by a cylindrical clay plug, molded separately and introduced from the bowl after the handle was joined to its exterior, (Fig. 25.)

|

| FIGURE 25.—LADLE FRAGMENT |

Miniature vessels (fig. 26).—These two tiny specimens are perhaps to be regarded as toys for small girls. The larger was crudely modeled and sundried; the smaller, on the other hand, is quite regular in shape and fired. On its inner surface are striations left by the scraping tool. Part of a third miniature vessel (312254) is also present.

|

| FIGURE 26.—MINIATURE VESSELS |

Effigy fragment.—Kidder and Guernsey27 found two small effigies on the surface at Ruin A, Marsh Pass. Our Betatakin fragment (312306) is the head from a very similar, though less realistic, specimen. The face is flat—a bit of gray clay pressed between thumb and index finger. The nose is not indicated; eyes and mouth are represented merely by pricks made with a bone awl or like instrument. From this head the neck and rectangular body, if any, have been broken. It should be noted that the specimen is unfired.

271919, p. 143.

Clay pellet (312314).—A flattish ball of molded red clay, 1-3/8 inches (0.034 m.) in diameter by 7/8 inch (0.022 m.) thick, is in the collection. With like balls, no doubt, village boys improved their marksmanship, for daubs of variate clay still adhere to the higher walls of Betatakin cave, clustered about casual targets.

LEATHER OBJECTS

Animals slain on the chase furnished flesh for hungry aborigines, bones from which their needed tools could be fashioned, hides suitable for clothing and other purposes. Implements of bone from Betatakin have already been listed; we are now briefly to consider the only two scraps of leather in our 1917 collection.

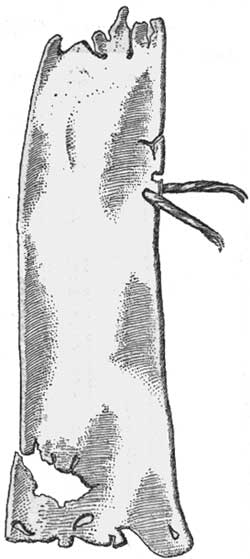

Figure 27 is part of a bag, made by sewing together with sinew two round-bottomed pieces of tanned hide. In their present condition these resist absolute identification. They closely resemble buckskin and yet are too thin. Perhaps mountain sheep hide was utilized. Whether or no, the bag when in use was approximately 2-1/2 inches (0.063 m.) in diameter. Rodents have gnawed away the upper portion.

|

| FIGURE 27.—LEATHER RAG FRAGMENT |

Figure 28 represents a trimmed bit of buckskin so well tanned that even to day it is as soft and pliable as a piece of chamois. It was perforated at each end for sewing; a fragment of cotton cord occupies a hole on one margin. Traces of white paint adhere to both sides.

|

| FIGURE 28.—PAINTED BUCKSKIN |

In these concluding paragraphs the reader is again reminded that this abridged description is not intended to convey more than a summary of the work of excavation and repair undertaken in the early spring of 1917. Other students of southwestern archeology have found need for certain architectural notes at our command and have urged their publication. But it is to be emphasized that our observations pertain only to the shell of Betatakin; not to the kernel within. Even though the privilege were properly ours we lack the essential data from which to write the story of this fascinating ruin.

The place of Betatakin in Pueblo history is well known. It was one of the last occupied cliff dwellings; its former inhabitants moved southwardly in late prehistoric times to unite with other clans, and these, in turn, migrated under pressure of nomadic tribes shortly before advent of the Spaniards in 1540. But Fewkes has drawn too short a trail from Betatakin to the modern Hopi villages; has accepted too literally, I am sure, the traditions of his Hopi friends. Future exploration and painstaking attention to details should shortly identify those sites at which the Betatakin folk successively lingered after they abandoned Segi Canyon.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

nava/si-2828/sec3.htm

Last Updated: 26-Jun-2008