|

OCMULGEE

Guidebook 1940 |

|

| Ocmulgee National Monument |

ON DECEMBER 23, 1936, Ocmulgee National Monument was established by Presidential proclamation and placed under the jurisdiction of the National Park Service, United States Department of the Interior. Development of the area started in 1933 through a series of archeological investigations financed with Federal emergency appropriations and supervised by experts of the Smithsonian Institution. Since establishment of the area as a national monument, the Civilian Conservation Corps has entered into practically every phase of its development through the contribution of funds and labor, technical supervision being given by the National Park Service.

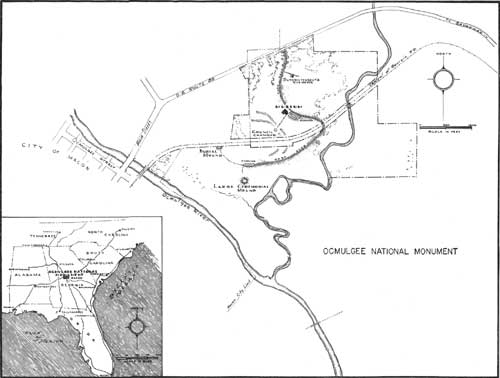

The monument lies east of the city of Macon in the heart of historic Georgia and is bounded on the southwest by the Ocmulgee River, a winding, muddy stream. The entrance is from United States Highway 80, which leads from Macon to the seacoast city of Savannah. Free guide service is available to all visitors; organizations or groups will be given special service if arrangements are made in advance with the acting superintendent. All communications should be addressed to the Acting Superintendent, Ocmulgee National Monument, Macon, Ga.

The Ocmulgee National Monument area is divided into two portions. The larger, 638 acres, lies on a series of bluffs, flat and extensive on top, and encircles the meandering course of the Ocmulgee River. Upon the tableland expanse of these bluffs are located the remains of several ancient Indian civilizations in the form of seven prehistoric mounds, an elaborate fortification system, a ceremonial earth lodge, a cultivated field buried beneath a mound, an ancient trading post, and a few Indian burial mounds. South and east, following the winding course of the Ocmulgee, at a distance of two and a half miles from Macon, lies another tract of about 40 acres known as the Lamar area, the development of which has not yet been completed.

BACKGROUND OF OCMULGEE

About 800 years ago bands of Indians from the north or northeast invaded the pleasant, game-stocked country of central Georgia and settled in the area of the present monument after displacing an earlier population. These Indians, called Swift Creek, built no mounds on Ocmulgee, but in their old village they left distinctive tools and utensils. They were defeated by another strong tribe, the Macon Plateau Indians, who came from Tennessee and Kentucky around the year 1350. The Macon Plateau Indians built the huge mounds, the fortified village, the ceremonial earth lodges near the Ocmulgee River, and grew corn, squash, beans, and tobacco in the fertile fields. Unmolested for a time, they in turn were probably either absorbed or driven out by the Hichiti tribe, a branch of the powerful Creek Confederacy. The Creeks continued to live on the banks of the Ocmulgee until about 1720, trading and fighting with the ever-threatening white men.

On the 40-acre tract south of the Ocmulgee site there was another Indian civilization which followed upon the occupation of the Macon Plateau Indians; this culture is called Lamar, after the site name. The inhabitants built mounds and lived inside a stockaded village that was similar in some ways to the village on Ocmulgee itself.

Even though the settlements tended to disappear with the westward movement of the white man, the significance of the remains has long been appreciated. William Bartram, English scientist and explorer, wrote about them in 1793; and since that time references to these mounds and villages frequently have been made. But even though the area was known as "Indian Mounds" the visitors did not envisage the extensive civilization that lay buried in the fields.

THE SIGNIFICANCE OF OCMULGEE

The area is significant archeologically for several reasons. It represents an extreme concentration in a relatively small area of archeological remains that have yielded considerable information concerning the almost unknown early history of the southern United States. Ocmulgee represents a zone or location where many important prehistoric and historic cultures overlap. Recorded on this area are presumably continuous Indian occupations representing four major cultural influences: the Swift Creek, the Macon Plateau, the Lamar, and the historic Creek Indians. In the spectacular exhibits at Ocmulgee—the mounds, buildings, tools, utensils, and bones—the visitor can appreciate the significance of the civilizations that preceded and existed at the time of the coming of the white man.

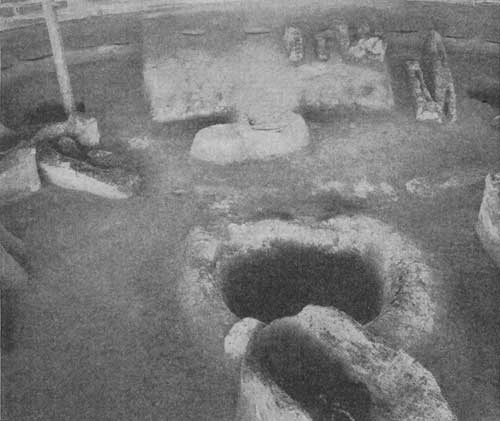

The interior of the Ceremonial Earth Lodge looked like this to the archeologists excavating in the area; note the fire bowl, the eagle effigy platform, the ancient charred timbers, and the post molds |

The Ceremonial Earth Lodge, after restoration, is like the original in almost every detail; today the visitor to Ocmulgee sees the interior as pictured here |

Archeological Features at Ocmulgee National Monument

CEREMONIAL EARTH LODGE

ARCHEOLOGISTS, by complicated scientific comparisons, have arrived at rough computations they are accustomed to call "a relative chronology" which may define in time the successions of Indian occupations and the cultural peculiarities uncovered in the ground on which these different groups lived.

Through their studies, the archeologists have determined that about 500 or 600 years ago the Macon Plateau Indians, who had displaced the Swift Creek Indians at Ocmulgee, constructed a building for governmental and religious meetings. Against the west wall of a unique circular structure, about 42 feet in diameter, a raised platform designed like an eagle's head was built in clay. The 3 seats on this platform were probably for the chief of the tribe, the medicine man, and the principal warrior, while minor officials or members of the council were seated in the 47 individual seats on a raised baked clay bench around the walls. All attendants at a meeting faced the deep fire bowl in the center of the room, wherein a sacred fire was supposed to burn continuously.

The reconstruction of this lodge was undertaken by expert archeologists, who carefully studied the remains before attempting restoration. Combining knowledge of historic and prehistoric buildings of this type with examination of the material evidence, the archeologists were able to conceive the structure as it once stood. A test trench dug in the area led to the discovery of the original wall. Careful investigation brought further evidence to light; the charred timbers and reeds of the original roof were undisturbed until the floor of sun-baked river clay was reached. The main outlines of the whole structure soon appeared.

Restoration followed excavation. The same kinds of oak and pine originally used were placed in the four original post molds that formed a perfect square about the sacred fire bowl. The roof was reconstructed exactly, with an outlet above the fire bowl providing a source of ventilation in the windowless wood, cane, and mud building.

The visitor today enters the building, which has a steel reinforced concrete dome protecting it, through a low entrance tunnel lined with woven cane matting, the pattern of which duplicates the original. Inside the structure the preservation of the fire bowl, eagle effigy platform, and seats has been accomplished with such accuracy that a council meeting might well be held there today.

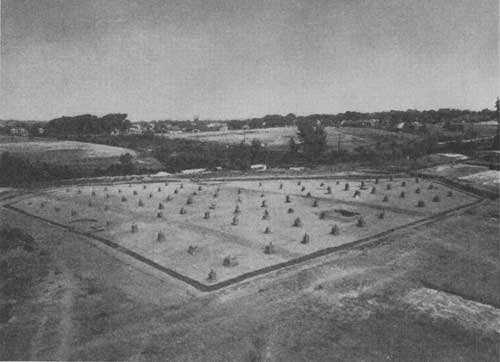

PREHISTORIC DUGOUTS OR FORTIFICATIONS

During the excavations in 1935 and 1936, two long series of large, pitlike structures were uncovered along the upper slope contours and rim of the Macon Plateau. These pits are prehistoric dugouts carved out of the red Georgia clay by the Indians who lived on the mile-square flat hilltop. They are long, oval excavations, 15 to 20 feet wide, 25 to 60 feet long, and 3 to 11 feet deep, and run continuously around the northeast, north, northwest, southeast, and southwest margins of the plateau. There is a strong probability that the entire hilltop was once completely enclosed by these chains of linked pits or dugouts. During the occupation of the hilltop by the Macon Plateau dwellers, the dugouts gradually filled in with blown sand; red loam and detritus washed over the slopes from the heavily settled prehistoric village. Thousands of artifacts and much Indian pottery, along with other objects, accumulated in the trenchlike pits as generation after generation lived on the plateau. Occasionally the villagers buried their dead in the dugouts. Also there are some dugouts that have thick deposits of materials on floors. Small round pits in the bottom of the dugouts were found to be filled with refuse discarded by the villagers. Over two years were taken by the archeologists to remove the filled earth in the prehistoric dugouts. Thousands of objects were found and catalogued. During the four years which have elapsed since the first discoveries of the prehistoric dugouts, much speculation has existed regarding the purpose of this remarkable series of pits around the edge of the Macon Plateau. Three theories have been offered at one or another time by different archeologists. The first explanation given was that the pits were borrow pits, representing the quarrying activities of the plateau dwellers seeking clay for mound building and the construction of sod-covered houses like the Ceremonial Earth Lodge. A later view was to regard the dugouts as the ground plan of a long series of pit-house residences encircling the plateau. The third theory, and the one probably favored by most archeologists, is that the two dugout lines represent trenchlike fortifications and that the use of these excavations as sod-covered pit houses was secondary.

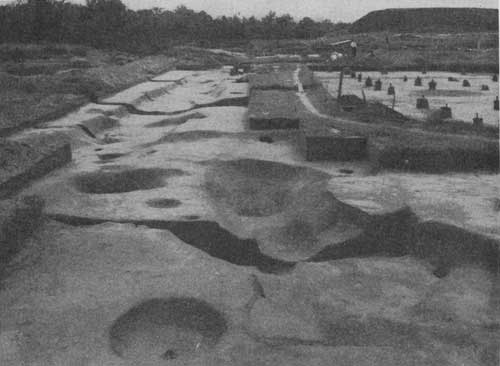

CULTIVATED FIELD

Near the point where the innermost line of prehistoric dugouts cuts through in front of the Ceremonial Earth Lodge is the half-explored remnant of a low flat mound. The mound is in back of the Earth Lodge, lying close to the dugouts which sweep north and west around it. Beneath this Indian mound, in excavations of 1935, the archeologists made a discovery which ranks in importance with the prehistoric Earth Lodge. Underneath the base of the mound, on the original ground surface, was uncovered a series of parallel rows of dark, rich, chocolate-colored earth, the unmistakable relic of a prehistoric cornfield, preserved perfectly intact for hundreds of years after the prehistoric plateau dwellers built the Indian mound on top of the abandoned cultivated field. An area of at least 75 by 50 feet of the cultivated plot was mantled by the earth cover of the Indian Mound. The original soil that the Indians cultivated, probably some hundreds of years before the time of Columbus, was a dark, rich, clay loam, chocolate red or magenta in color. The Indian mound was built of white or tan-colored sand, brought up in basketloads and dumped. The top of the mound was completely covered over by thick red clay, averaging 14 inches in thickness, impervious to water and hardening to stony consistency under the semitropical heat of the Georgia sun, thus affording effective protection against the elements for hundreds of years.

The Indian method in corn planting was to cultivate each corn plant in a small separate hill. The prehistoric cultivated field on the Macon plateau shows definite rows, paralleling one another and extending toward the periphery where the mound cover stopped. A portion of the cornfield still extends back under the remaining unexcavated portion of the Indian mound.

The Indian mound over the cornfield clearly demonstrates what is meant by the archeological term "vertical stratigraphy," the time differences indicated by the relative positions of layers of earth showing occupation. Because the prehistoric Indians here built a mound over an earlier cultivated field, the structural layers have been excellently preserved.

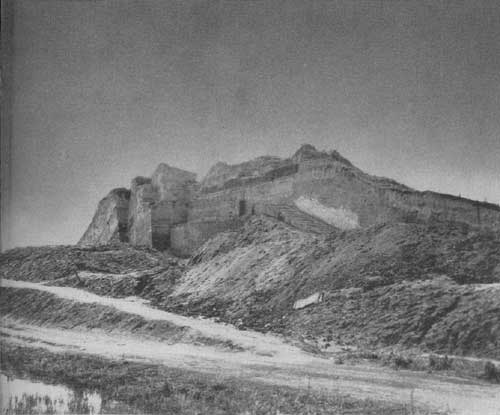

The trenches surrounding the village of the Macon Plateau Indians probably served as a defense against surprise attack; only a small portion is shown in this picture |

TRADING POST

Throughout the Colonial period the Indian trade was the chief instrument of westward expansion. Its importance can readily be seen in the attempt of English traders to win the friendship of the Creeks from their previous Spanish alliance. It was the urge of a highly profitable trade that led these traders far into the southern wilderness.

The five-sided structure now known as the "Trading Post" was discovered at Ocmulgee by archeologists in 1936. Although historical research has not yet definitely established this as an early English trading post, there is considerable material to substantiate the inference. It is believed that the post was built and operated between 1690 and 1715 by the English traders with the Creek nation. Here the English, under the leadership of Gov. Nathaniel Johnson of South Carolina, probably exchanged guns, knives, beads, swords, and other similar articles for the skins and furs brought in by the industrious Creeks. Within the five walls that enclosed the area evidence of several rectangular log cabins has been found. These may have been used for storage of trade materials or possibly for living quarters by the early traders.

The ridges in this picture are the only visible remnants of an ancient field in which prehistoric Indians centuries ago probably cultivated corn in much the same manner as the farmer today. The prehistoric American Indian had no plow. He used stone or shell hoes, pulling the earth up in hillocks which ran continuously end on end, thus simulating the appearance of rows. The house, the site of which is clearly visible in the foreground, was also built by prehistoric Indians. The excavators in the picture are digging through the low, flat mound that was erected over both field and house site |

The size and shape of the Trading Post can be seen clearly by visitors. There is a broad base side, 140 feet long, facing the river toward the northwest. Two shorter sides or legs set at right angles to the base extend 40 feet southeast. The two remaining sides, 100 feet in length, converge to form a triangle or gabled point to the southeast. The walls of the stockade are indicated by a trench or ditch, varying from 18 to 24 inches in depth and from 10 to 14 inches in width at the top, in which posts probably were set. Since there were two breaks in the continuity of the trench on the base side, one 12 feet wide, the other 5 feet wide it is assumed that there were 2 gates opening into the stockade from the river approach. Parallel to four of the five sides a moatlike trench or ditch was uncovered; similar to the ditch that encircled the prehistoric village, it may have served the same purpose of defense.

On this site there was erected a trading post, probably between 1690 and 1715, by English frontiersmen seeking the skins and furs collected by the Indians. A stockade surrounded the five-sided structure, and rectangular log cabins for storage or living quarters were erected within the stockade. The little pilasters of earth left within the enclosure are small blocks of unexcavated soil left under the survey stakes showing the depth and profile of the excavation |

The profile of an old beaten trail leading to the Trading Post has been traced for three quarters of a mile through the monument area. It is probable that this trail is the "Old Traders Path" referred to by Benjamin Hawkins, of South Carolina, an early visitor to the Ocmulgee area.

The excavations that have been made in the Ocmulgee area have yielded a great store of European trade material and seem to be associated with the Trading Post. The number of artifacts uncovered lend credence to the belief that there was a rather large population of Creek Indians living near the post. In addition to war material—guns, knives, bullets, and pistols, always primary articles in early trade with the Indians—such articles of trade as beads, clay pipes, iron axes, and copper and brass bells were discovered.

These moatlike trenches outside the trading post walls may have served the traders as further defense against attack. In the pits seen in the picture archeologists discovered a great quantity of European trade material, such as guns, knives, beads, and iron axes |

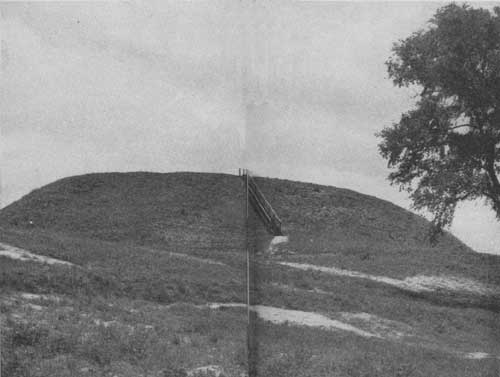

LARGE CEREMONIAL MOUND

Of the seven prehistoric mounds in the Ocmulgee area the most spectacular has been called the Large Ceremonial Mound. One of the largest in the Southeast, it was originally 40 feet high and 300 feet wide at the base. It is a huge pyramidal structure, towering 105 feet above the river plain, and from the top of it there is an excellent view of the Ocmulgee Valley, the outspread monument, and the adjacent country.

The Large Ceremonial Mound, one of the largest mounds in the Southeast, was used primarily for religious ceremonies |

|

(image omitted from the on-line edition) This skeleton of a robust Creek Indian man, interred with a girdle of copper bells, is one of many discovered by the archeologists at the monument |

The mound was probably built between 1350 and 1500 by the Macon Indians. Construction was a laborious project, for the dirt and clay had to be transported in baskets on the backs of the natives. At least four times during its construction the Indians decided that the mound was large enough, so they capped the portion that had been completed with a thick layer of clay and built a ceremonial structure upon it.

The excavations that yielded the evidences of this interrupted building process also uncovered a clay floor and fire bowl on top of the mound. Thus there may have been a ceremonial structure at the peak of the mound, which probably also served as a lookout.

BURIAL MOUND

This large truncated mound, commonly referred to as a burial mound, might better be described as a combination temple and burial mound, for although there were 110 burial remains found here there was evidence that a ceremonial structure was erected on each of the five building levels. As a site of the past customs of prehistoric Indian groups, however, it has great significance.

A large conical structure, 30 feet high and over 200 feet long, the mound in cross section showed five series of banded clays, each of different color, consistency, and thickness, and each marking the summit of an earlier unit of mound construction. Each mound was conical in shape with a flat summit, topped by clay 12 to 14 inches in thickness.

The topmost burial pits are of relatively recent date, glass trade beads and iron objects having been found definitely associated with the skeletons. The pits within the mound represent predominantly secondary burials; that is, the bodies were exposed or reburied in the mound pits, only the long bones, skull, and jaws having been moved in the final reburial.

Underneath the base of the mound six log tomb burials were uncovered. These tombs were 9 to 11 feet long, 4 to 6 feet wide, and 2 to 6 feet deep, each containing from 1 to 6 bodies of men, women, and children. In some instances there is evidence that the tombs were lined with bark or small saplings. Shell ornaments, bone artifacts, and both shell and bone beads were used in these sub-mound interments. The arrangement of the bodies in multiple burials and the occasional wrapping of a corpse in hides or bark before burial in the log tomb imply an elaborate ceremony.

This vertical cut or profile was made through the east shoulder slope of the Burial Mound. The mound is a mosaic structure, really five mounds in one, each new layer built on a preceding layer. Note the striking banding of colorful clay streamers superimposed over sand fill, dumped in place during construction. In the foreground two burial pits originally cut through the clay slopes of an earlier stage of mound building can be seen |

|

(image omitted from the on-line edition) In this prehistoric burial six individuals were interred in one grave, and periwinkle shell beads and a large conch shell were used as burial furniture |

The north face of this mound has been exposed so that the five building levels can be seen clearly by the visitor. This cross section shows a marked selection of different kinds of sand and clay used in the five units of construction. Even the 14 clay steps leading from the base to the top of the first building stage are clearly visible.

The ceremonial structures, evidences of which were found at the top of each of the five levels, may have been used for the purpose of preparing the dead for burial.

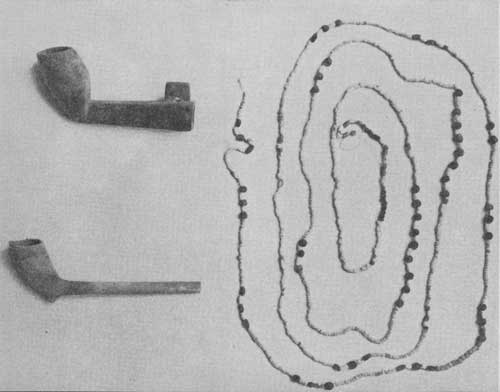

BURIALS

The Indians of the Southeast do not seem to have had any uniform method of burial. It was customary, however, for most tribes to bury with their dead some objects belonging to the deceased. The archeologist can then determine roughly the time of burial by the type of artifact uncovered with the skeleton. In the burial places of the prehistoric Indians of the Ocmulgee area have been found stone implements, pottery, clay pipes, shell and bone beads, ornaments, and sometimes large conch shells; in the graves of the later Creek Indians guns, pipes, swords, glass beads, bells, axes, iron ornaments, and similar articles have been discovered.

In and around the Trading Post the remains of hundreds of Creek Indians of many ages and both sexes were found. At this time the deceased was buried with his legs folded against the body, after the skull had been artificially flattened. Cremation does not seem to have been practiced until after the European infiltration, and even then the custom of placing personal belongings with the corpse was followed.

Since a number of the burial places discovered at Ocmulgee have been left open for inspection, the visitor, by comparing the different ornaments and tools found with the skeleton, can re-create to some extent the life of the individual.

|

(image omitted from the on-line edition) By means of such discoveries as these bells, buttons, and other iron decorations found in historic Creek burials, archeologists form a picture of the first white and Indian contact in this region |

These clay pipes and Venetian beads were probably received by some Creek in return for his furs |

The nature trail that winds through a portion of the monument area is a haven for a great many species of birds and flowers native to the region |

The Museum and Nature Trail

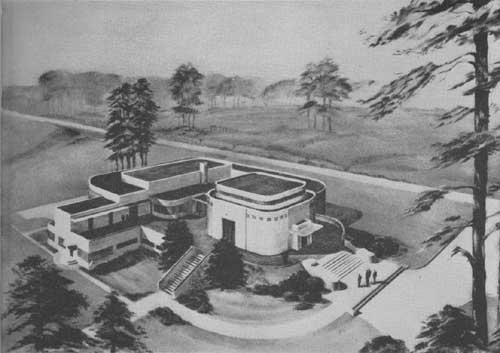

THE NEW and modern museum will be located at the eastern edge of the archeological area in an open grove of pines and gums. From the large windows in the rotunda, the rustic bridge and pathway to the council chamber will give the visitor his first glimpse of the restored Ceremonial Earth Lodge and the site of the prehistoric fortified village of the Macon Plateau dwellers.

In the exhibition rooms will be shown the tools, ornaments, and activities of the early occupants, conveniently arranged in groups corresponding to the several Indian occupations of the area. Models and dioramas will present the archeologist's reconstruction of the chief features of Indian life.

In the laboratory, archeologists will prepare scientific reports and supervise the reconstruction of almost a million fragments of pottery and stone artifacts recovered during the investigation. These collections, coming from five years of continuous exploration, will constitute a source of scientific information of primary importance to all students of Southeastern prehistory for many years to come.

An interesting feature of Ocmulgee National Monument is the attractive nature trail near the Large Ceremonial Mound. Winding through the heart of a typical Southern swamp and remote from the usual path of visitors, this narrow trail passes through a bird sanctuary and garden. More than 95 species of Southern birds have been identified in the area, and dogwood blooms, crab apple, magnolia, hawthorn, wisteria, and other flowering plants line the walk. Amateur or professional botanists and biologists, as well as the casual visitor, will keenly enjoy this feature.

The proposed museum has been designed to serve as a center for archeological studies in the Southeast. Here the visitor will be able to see the collection of material found at Ocmulgee and to learn the background of the area he is about to explore |

OCMULGEE NATIONAL MONUMENT

(click on image for a PDF version)

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> |

1940/ocmu/sec1.htm

Last Updated: 20-Jun-2010