|

Oregon Caves

Historic American Buildings Survey Oregon Caves Chateau |

|

HISTORIC AMERICAN BUILDINGS SURVEY

Oregon Caves Chateau

(HABS No. OR-145)

Oregon Caves Chateau

| Location: | Oregon Caves National Monument Terminus of Oregon Route 46 Josephine County Oregon U.S.G.S. Oregon Caves Quadrangle (7.5') Universal Transverse Mercator Coordinates: 10.466450.4660620 |

| Present Owner: | Estey Corporation (concessioner) 5000 N. Lagoon Avenue Portland, OR 97217 The site is leased from the National Park Service. |

| Present Occupant: | Concession employees and hotel guests. |

| Present Use: | Seasonal hotel, dining facilities, quarters for concession staff. |

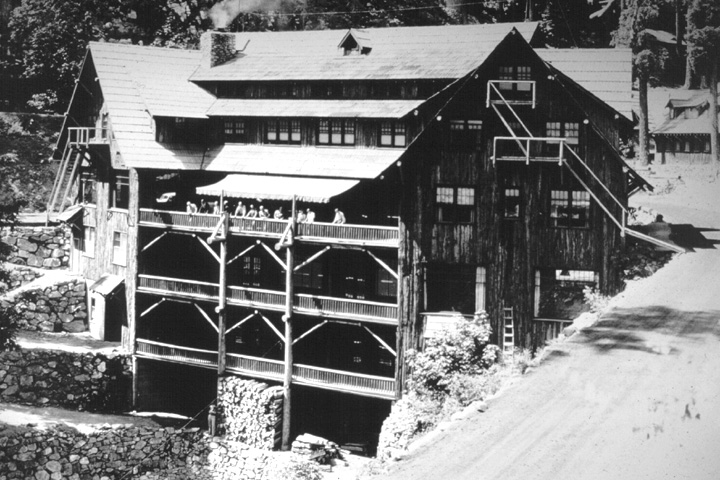

| Significance: | Like the Ahwahnee Hotel at Yosemite and the Old Faithful Inn at Yellowstone, the Oregon Caves Chateau has become almost a part of the primary resource at the monument and is definitely part of its image. Spanning a small gorge only 25 yards from the cave entrance, this six-story rustic hotel was designed and built by Gust Lium, a local contractor, during the years 1931 to 1934. In accommodating the width of the gorge, the structure's steep gable roof of intersecting parts and dormers fit the rugged topography of the monument, as did its sheathing of Port Orford-cedar bark. Much of the hotel's mass is hidden below road level and away from view so that its appearance belies its size, which is further downplayed by the extensive landscaping with native stone and indigenous plants. It is so well integrated into the site that architecture and landscaping are wedded both in and around the structure; its central location has also made it the hub of past planning and design work at Oregon Caves. |

PART I. HISTORICAL INFORMATION

A. The Site

1. Setting

Located in the Siskiyou Mountains of southwest Oregon, the site of the chateau is approximately 4000 feet above sea level. As part of the larger Klamath Mountain physiographic province, the Siskiyous are characterized by oversteepened topography, complex geology, and whose diversity of endemic North American flora is matched only by the southern Applachian region. Except for the Whiskeytown-Shasta—Trinity National Recreation Area in California, the 480 acre Oregon Caves National Monument is the only representative of the Klamath—Siskiyou ecotype in the National Park System.

The developed portion of the monument consists of an area around the cave entrance and a lower parking lot, which are connected by a narrow roadway situated above a canyon formed by Cave Creek. A gorge is formed where a normally dry ravine to the southeast of the main cave entrance meets Cave Creek. The cave entrance area has considerable landscaping whose purpose is to make the development blend with the rugged topography. This is done by utilizing native stone to define roads and pathways, while a variety of trees, shrubs, ferns, and flowers serve to screen structures and soften the appearance of the rock retaining walls.

While the monument's developed area is about 30 acres, much of the backcountry can be reached by an extensive network of trails. Their hub is the cave entrance area, which allows visitors to take a cave tour and then hike to attractions on the monument like Big Tree, or to the high country located in the adjacent Siskiyou National Forest. The failure to expand the size of the monument, however, is evident in the size and extent of several visible clearcuts located on the surrounding national forest land.

2. Design Summary

Although Oregon Caves was one of the first national monuments, its remote location virtually precluded permanent improvements until 1922. That year a road reached the cave entrance area from the northwest and stimulated the U.S. Forest Service (who administered the monument from its establishment in 1909 until it was transferred to National Park Service control in 1933) to draw up a general plan for improvements. The agency sought a concessioner that had sufficient capital to provide visitor services and who would create an appropriate atmosphere for one of the few national monuments developed under the auspices of the Forest Service.

Hotel accommodation for visitors was proposed as early as 1891, but no serious plans for resort development at Oregon Caves took shape until 1912. That year an auto road reached Holland (some 15 miles west of the cave) from Grants Pass, and a Portland group announced plans to finance construction of a hotel that would be placed on the site of the present chateau. Local businessmen began clamoring for a road to the cave, but this project was held up pending clarification as to whether the cave could be electrically lit and admission charged. A Department of Agriculture solicitor's opinion was that the Forest Service had no authority to issue permits for building resort facilities on national monuments. In 1915, Congress passed legislation that authorized the Forest Service to lease land for resort development, but the agency decided not to grant any permits for a resort at Oregon Caves until an auto road reached the monument.

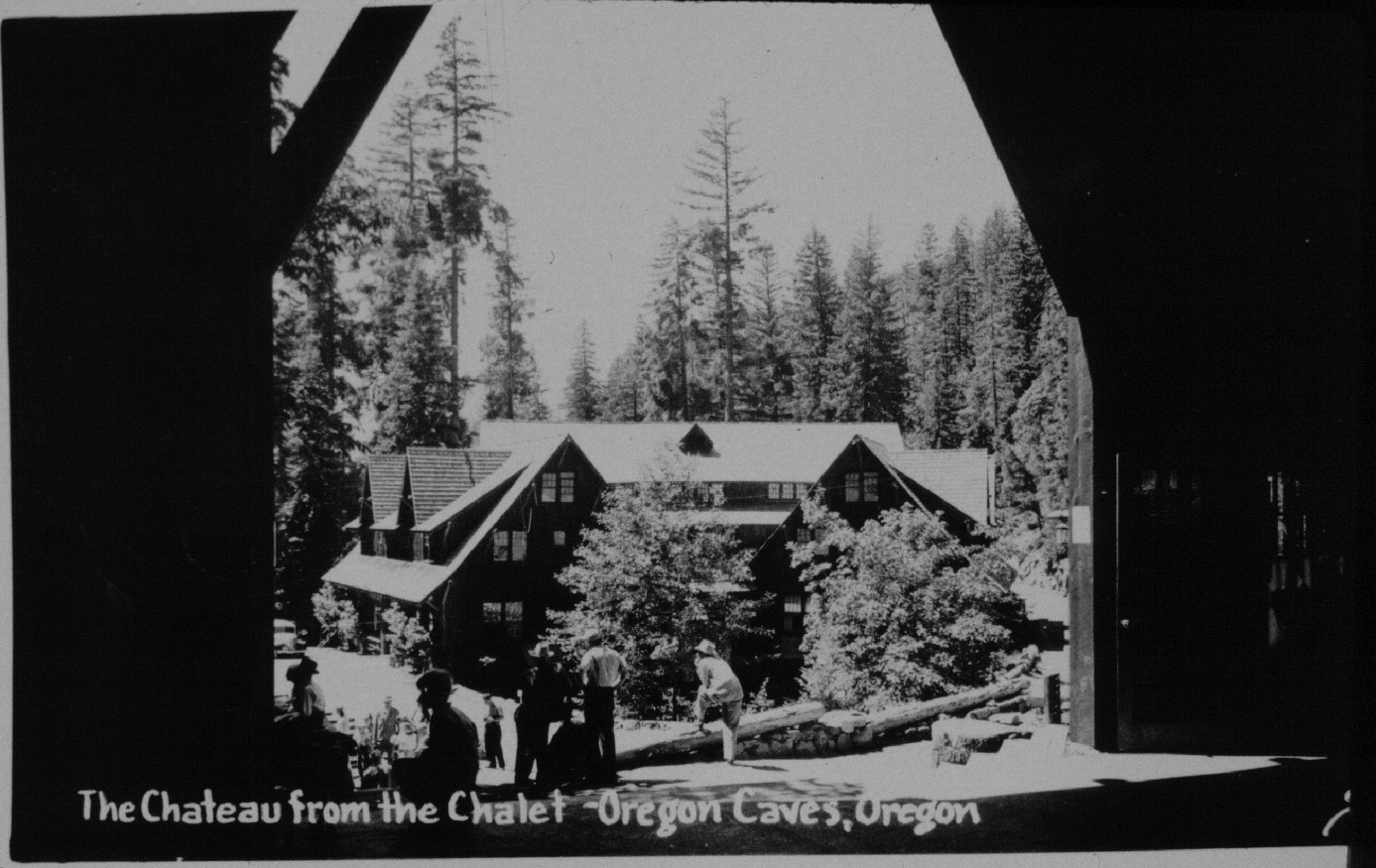

In 1923, a group of local businessmen from Grants Pass were awarded a contract to provide guide service in the cave and develop a resort. They immediately constructed the monument's first permanent building, a "chalet", which occupied a terrace in the dry ravine near the cave entrance. The development was somewhat unusual because the architectural plans were drawn concurrently with a landscape plan which set the circulation pattern for the area, utilized the Forest Service's newly built trail system, and identified cedar bark sheathing as a conspicuous part of the development's appearance.

An open archway connected the two parts of the original chalet together, at which was the beginning of a path to the cave entrance. The path continued uphill to the rear of the building to become a trail with "one or more small buildings as on an irregular street." [1] By 1926, seven cabins and a small enclosure known as "Kiddy Kave" lined the trail. All had cedar bark sheathing, as did a guide dormitory perched on the hillside to the north of the chalet.

Planning for a hotel to be located across from the chalet began in earnest during 1929. Passage of a bill authorizing the Forest Service to spend $35,000 to build an exit tunnel for cave tours and light the cave with electricity was announced, so demand for overnight accommodations was expected to dramatically increase. The hotel was to be "so built that the water coming from the caves will flow through the dining room in a creek bed made for it bridged by rustic bridges. The hotel. . . is designed in Swiss architecture, fitted into the local scenery in such a way that it will add to the natural beauty of the canyon and the towering trees." [2]

When construction began in 1931, the chateau's unique design was said to be "perhaps inspired by the vaulted caverns. . . Its conformation is that of two parallel lines, one longer than the other yet joined by diagonals that constitute angles of identical degrees." [3] The hotel immediately became part of the monument's image, to the extent that it seemingly became part of the cave. It captured part of Cave Creek through a basement culvert and routed it through the dining room, while the configuration of rooms and stairways could remind visitors of a cavern punctuated by windows. The centerpiece was a double-sided marble fireplace in the lobby which contained a miniature cave at about mantle level on one side.

As the hotel opened its doors, landscape projects were begun by Civilian Conservation Corps enrollees. From 1934 to 1941, design work was done by National Park Service landscape architects and executed by C.C.C. crews. One of the earliest projects was the construction of two rock—lined trout pools. Each was fed by separate waterfalls; one pool is just below the cave entrance, while another is in the chateau's courtyard.

In much the same way that the building of the chateau was influenced by the limitations of its site, the only NPS structure in the cave entrance area was begun in late 1935 and completed in mid-1936. Located next to next to the group of cabins, the ranger residence is banked into the hillslope and is sheathed with cedar bark. Stylistically, it resembles a guard station built by the same C.C.C. enrollees about eight miles away on the Caves Highway. The construction of the ranger residence meant that all future NPS building on the monument would have to take place in the lower parking lot because these quarters occupied the only site not already leased to the concessioner.

The steadily climbing visitation toward the end of the 1930s necessitated that the NPS formulate its first master plan in late 1936, something that was revised in 1938. This was done for several reasons: the agency wanted to have an instrument that would exercise some control on the concessioner's plans for expansion, it contemplated projects whose costs for materials exceeded the C.C.C. allotments that it had formerly depended upon, and there was the desire to conform to the policy that all areas administered by the NPS should have a master plan.

The concessioner wanted to expand his operation in 1938 and drew up plans to enlarge the guide dormitory, erect a female employee dormitory across from the cabins, and build a new chalet that would include 50 rooms for overnight guests. Two years of negotiations with the NPS followed, the result being that the guide dormitory was enlarged (with the noticeable change that peaks were added above second floor windows), the women's dorm was incorporated into the design for a new chalet, and the 50 additional rooms were dropped. A new chalet was started in November 1941 and finished in early 1942. It incorporated an open two-story breezeway, a wide variety of doors and windows, and, despite a vastly different configuration, somehow seemed to complement the chateau.

Park Service projects in the cave entrance area during this period were largely confined to landscape and utility projects. The use of the native rock in the landscaping was particularly notable: it was used to form rock benches along the trail to Big Tree, combined with masonry in the construction of two fire hose cabinets and for several retaining walls, as well as for a curb in front of the chateau. Prominent amongst the utility work was the installation of recessed lights along the exit trail and the addition of rustic lighting standards to line the main roads of the monument. This was done after receiving a special appropriation for a power line to be built from Holland, some 15 miles to the west.

The lighting design also extended to the concession development. Recessed lighting was placed near the cabins, while two lights (that were like those used on the standards along the monument's roads) were placed opposite of each other under the eaves of the chateau's south facade, not far from the hotel's main entry.

Another tie between the concession development and NPS design was a rustic sign in front of the gas station in the lower parking lot. Made of redwood with raised lettering, it was similar to the monument's entrance sign at the other end of the parking lot. The NPS sign is more elaborate, however, because it has two sides and is hung by a motif of Port Orford-cedar logs that is supported by a stone base. The gas station was removed in the 1940s after a slide had undermined it and the adjoining comfort station.

The key to the Park Service efforts at accentuating the monument's appearance was the presence of the chateau. It provided a precedent as well as a hub for the type of rustic architecture expressed at the Oregon Caves. In recognition of Lium's success in adapting the hotel to the site, the chateau was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1987 by the Secretary of Interior.

B. Plans and Planners

1. Forest Service planning, 1922

Siskiyou National Forest Supervisor E.H. MacDaniels drafted the first development plan when the first road reached the monument in early 1922. He called for a development to be placed in the canyon of Cave Creek, some 700 feet below the cave entrance. It was to be composed of a number of small cottages, "all of the same general style and of an accepted type of rustic architecture." [4] MacDaniels favored a design much like that proposed for a resort to be developed on Forest Service land at Union Creek, some ten miles west of Crater Lake National Park. During the year that it took to find a concessioner who had sufficient capital to build an appropriate development, this plan was amended by Assistant District Forester C.J. Buck to include a concession responsibility for operation of a guide service, cave tour equipment, meals, and limited lodging. [5]

2. The Peck Plans, executed by Gust Lium, 1923-34

The original concession development at Oregon Caves was supposed to be split between limited facilities at the monument and a resort to be constructed near the confluence of Grayback and Sucker creeks, about eight miles away along the Caves Highway. In March 1923, the newly formed Oregon Caves Resort got Arthur L. Peck to advise them on how to lay the grounds out on both sites. Peck, who taught landscape architecture at Oregon Agricultural College in Corvallis, advised the group of Grants Pass businessmen led by George Sabin to make use of a flat area within the ravine that lay about 100 feet east of the cave entrance. His idea was to construct "a good sized building on the terrace. . .with a porch from which a view of the entire lower valley could be obtained. He [Peck] would extend the porch beyond the house so that it. . .would form an entrance to the path to the Caves and also to the trail up the gulch leading to one or more small buildings as on an irregular street. There would not be many of these, as there is no need for them, the dining room and office being in the large building." [6]

Peck's choice of an architectural treatment for the resort was an "Alpine type", because it was "suitable to high elevations and surroundings of mountains and big timber." [7] The buildings were to be sheathed with Port Orford-cedar bark because it quickly weathered to an attractive silver grey color. To break the general lines of the buildings, Peck recommended a simple decorative scheme like brackets in the gables and shakes could be used to add interest to the roofs. He also suggested transplanting the native flora around the buildings, with particular emphasis on the ferns which would compliment the rockwork that had been placed in the cave entrance area as part of the Forest Service trail system.

Just who designed the old chalet remains unclear, but Peck's recommendations affected its construction. The buildings along the "irregular street" were not erected for another three years. In 1926, when the Redwood Highway that linked Crescent City, California, with Grants Pass was completed, a local contractor named Gust Lium designed and built seven cabins for the concession. All had shake roofs and cedar bark sheathing, but each had a slightly different roof and/or entry design of hips, peaks, or dormers. Lium also built a guide dormitory, locating it north and slightly upslope of the chalet instead of Peck's suggestion that it be west of the cave entrance.

The next phase of resort development was stimulated by passage of an appropriations bill for construction of an exit tunnel and lighting the cave by electricity. This 1929 legislation encouraged the resort's manager, George Sabin, to plan for a hotel in the cave entrance area. Peck was again brought in for advice and to legitimize the idea of building in the gorge formed by the ravine and Cave Creek. The land on which it was to stand had not been leased to the concession, so the Forest Service was able to renegotiate the special use permit of 1923 into a new agreement that redefined the concession's territory and responsibilities.

Whether Peck participated in the formation of a new development plan is unclear, but construction of the Oregon Caves Chateau began in September 1931 and was eventually completed in May 1934. As per Peck's suggestion, the concession's tent houses were removed and the path to the cave entrance was widened for a "public concourse area." [8] Related to the latter was the placement of a marble monument to the discoverer of the Oregon Caves, Elijah Davidson, just east of the cave entrance in the early 1930s. The new agreement also allowed the resort to construct a rustic filling station on south edge of the lower parking lot, near where a public comfort station was placed in 1933.

By doing the site planning for the resort development at the Oregon Caves, Peck established an appropriate precedent for the National Park Service efforts that began in 1934. He had come to what was later Oregon State University in 1908 to teach courses in the horticulture department on landscape gardening, but was influential enough to become head of a newly created department of landscape architecture in 1932, a post that he held until retirement in 1948. Peck (1882—1961) did much of the landscape work around present-day Corvallis, laying out its parks and much of the university campus. [9] His recommendations served to differentiate Oregon Caves from other resorts in the national forests, but this was not sufficient to prevent the monument's transfer to the National Park Service on June 10, 1933.

2. National Park Service planning, 1934—36

Formal transfer of the Oregon Caves to National Park Service administration did not take place until May 1934, the same month that the chateau opened its doors. A small group of Civilian Conservation Corps enrollees were dispatched from Crater Lake National Park to establish Camp Oregon Caves at the confluence of Sucker and Grayback creeks, the site the concession company had forfeited in the agreement of 1931. Throughout its seven year history, enrollees at Camp Oregon Caves did projects for both the Forest Service and the NPS. It was largely a winter, or "spike", camp that got most of its enrollees once Crater Lake's construction season was over for the year.

The camp's landscape foreman, Armin Doerner, wrote the first NPS planning report for the monument. He made recommendations for future road, trail, utility, and landscape work in May 1934 and was one of four men who agreed to a site for a future ranger residence in August 1934. Construction of the residence was postponed until late 1935 because C.C.C. allotments were restricted to $1500 for materials per project. In the interim, landscape work was guided by the recommendations of the agency's chief landscape architect, Thomas Vint, who ordered that the monument be kept as nearly natural as possible. Specifically, Vint ruled out placing structures or developing a campground in the canyon of Cave Creek. He recommended that the C.C.C. crews accelerate the landscape program that the concession had started by continuing the use of native flora in planting around the cave entrance area.

Vint (1894-1967) did much of the initial site planning in western national parks and monuments for the NPS. Specific designs for the components of the Oregon Caves development was left to personnel in the Branch of Plans and Design office in San Francisco, resident landscape architects appointed through the C.C.C. for parks like Crater Lake (who would also do work for the surrounding national monuments and state parks), and the landscape foremen assigned to Camp Oregon Caves. As foreman, Doerner did some design work for the landscaping that was done around the chateau in 1934. His successor was Howard Buford, who conceived the stone steps that lead from the cave entrance to the trout pool that is next to the campfire area. Buford served as landscape foreman until 1937, and it was during his tenure that landscaping around the chateau was started.

3. The Oregon Caves Master Plan, 1936 (revised 1938)

By late 1936, the National Park Service had decided to extend the use of its primary planning vehicle, the master plan, to the monument so that it could better defend its budget requests to Congress. Visitation was increasing to the point where the NPS wanted a way to avoid hastily-conceived ideas for development (its own or the concessioner's) by allowing each feature of the master plan to be studied by the various technical branches of the agency before administrative approval was given to proceed. During the 1930s, a master plan usually consisted of large, handcolored maps that were bound together in a roll. Inserted between the maps were detailed narratives that were updated in successive editions of each park unit's master plan.

The 1936 and 1938 master plans for the monument were drawn by Francis Lange, the resident landscape architect at Crater Lake National Park. Both plans were similar in style and scope to the considerably larger ones that he had done for the park. Included in the 1936 plan was expanded lower parking lot, extensive trail work, and removal of the guide dormitory. An appropriation of $20,000 in 1937 to improve the monument's lighting system (by eliminating generators in favor of a power line along the Caves Highway) led to an update of the master plan in 1938. Planning began at that time for an enlarged chalet, something that came to fruition three years later after lengthy negotiation between the concession and the NPS.

By 1941, visitation to the monument was beginning to take the form of being almost entirely day-use, so the concession decided not to expand the accommodations provided by the chateau. A landslide in the lower parking lot in 1940 undermined the filling station and restroom, so both were removed by C.C.C. enrollees during the fall of 1941. Replacing them was a structure that departed from the master plan drawn by Lange but had been discussed in form or another since 1934. This was a "checking station", but when built was actually an administrative office for the ranger assigned to the monument. It was combined with a comfort station and represented the last project completed by enrollees before Camp Oregon Caves was disbanded. The structure was built under the supervision of Lester Anderson, the resident landscape architect who replaced in Lange in 1940, and who was to complete an abbreviated version of a master plan for the monument in 1942. Unlike the master plans that preceded it, however, the plan of 1942 was not an operative document because of the small amount of management activity during the war and the formulation of a far more extensive master plan in 1945.

Although master plans were the product of a consensus process, Francis Lange was the most prominent landscape architect involved because he was in the position to influence design decisions as resident landscape architect from 1934 to 1940. Lange (1904— ) began working seasonally for the NPS in 1922 and was hired as a full-time landscape architect in 1929. After completing a masters degree in landscape architecture at Washington University in St. Louis during 1933, he became the resident landscape architect at Crater Lake National Park in 1934. His winters were occupied by doing design work, some of which was for Oregon Caves. He became an assistant landscape architect in 1940 and was stationed in San Francisco, where he stayed until he left the Park Service in 1943. [10]

C. Physical History

1. Date of erection: After a well-publicized start in September 1931, work slowed during 1932 due to financing problems. The hotel was opened in May 1934 after the builder accelerated the work schedule to meet a stipulated completion date.

2. Architect/Builder: Gust Lium designed and built the structure. The appearance of the finished hotel differs somewhat from pre—construction drawings that appeared in local newspapers. Lium's divergence from these drawings certainly benefitted the finished building, as did the subsequent landscaping that was largely done by Civilian Conservation Corps enrollees under the supervision of National Park Service landscape architects. In addition to fitting the chateau's configuration to the site, Lium should be given credit for the extensive use of local materials throughout the building. Native marble was used to make a massive double fireplace for the hotel lobby. Madrone, white oak, Port Orford-cedar, ponderosa pine, and Douglas-fir were used in a variety of ways, from enormous structural beams to staircase balusters. The atmosphere of the 1930s is re—created inside the chateau by an astute blend of native materials with wrought iron fixtures, wood frame windows, and many pieces of arts—and—crafts furniture.

Lium (1884-1965) was a locally prominent architect and is credited with many structures in Josephine County. His work on Forest Service lands began with the design of seven concession cabins at the Oregon Caves in 1926 and continued after the chateau's completion. From 1936 to 1940, he was employed by the Forest Service to design structures that were being constructed as C.C.C. projects. His association with the chateau was such that during the last year of his life he helped direct repair efforts after the flood damage of 1964.

3. Original and subsequent owners: Oregon Caves Resort (renamed Oregon Caves Company in 1953) which transferred its holdings to the Canteen Company of Oregon in 1977. Canteen was renamed Estey Corporation in 1988.

4. Builder, contractor, suppliers: Most of the lumber for the hotel came from the Grayback drainage located about eight miles northwest of the monument. The chateau's cedar bark sheathing came from a railroad tie cutting operation in the same area. California redwood was purchased from a regional supplier and used as roof shakes and wainscoting. A type of pressed fiberboard called "Nu—Wood", came from a manufacturer in Minnesota and was used for wall and ceiling surfaces. Just prior to the building's opening, the concession received two railroad car loads of furniture and fixtures, much of it made especially for the chateau.

5. Original plans and construction: The original floor plans are on six sheets and carry no number. A separate sheet for the kitchen layout bears a date of September 23, 1931. Plans showing the chateau's elevations have not been located, but several photos in the possession of the concessioner show the building during construction and immediately after completion. Original cost of the structure was $50,000.

6. Alterations and additions: Most of the changes in the chateau can be tied to the damage caused by the 1964 flood, but several others are noteworthy. Changes to the original floor plan are most prevalent in the first basement (the third story from the bottom of the building). A coffee shop was created from storage space in 1937 and differs from the "Coffee Tavernen" on Lium's plans. It was furnished with a soda fountain placed along the room's south wall. In 1954, the coffee shop's seating capacity was increased from 23 to 45. The soda fountain was moved to the west wall, while a partition wall, restroom, and stairway were removed. That year part of dining room was converted into a cocktail lounge, which was rebuilt in 1965 after the flood.

During the 1964 flood, the chateau's first floor gave way, so that the debris inundated the three basements. The resulting damage necessitated removal of the coffee shop's oak parquet floor and the maple dance floor in the dining room. Special woods were ordered to match the original walls on this floor and the first floor above it. Much of both floors had to be carpeted, and the stairway balustrades had to be replaced through careful doweling by hand.

One of the few changes to the lobby prior to the flood was the extension of the reception desk to the south wall for a display case. The kitchen was remodelled in 1947 and an automatic sprinkler system was installed throughout the building in 1950. Additions were made to the building's sprinkler system (extent not specified) in February 1961. The most notable change in the chateau's exterior: the wooden porches (verandas) were condemned and removed in favor of steel fire escapes and catwalks November-December 1958. This was after irreparable damage by that winter's snow load, so steel fire escapes were installed to replace them. Other exterior changes occurred in 1954, the year when a ramp was added from the kitchen to the employee dining room and a plate glass window was introduced to the north side of the entrance to the coffee shop.

PART II. ARCHITECTURAL INFORMATION

A. General Statement:

The Oregon Caves Chateau's prime significance lies in how its designer-builder, Gust Lium, used the building site to dictate a design for the hotel. Lium took a difficult architectural problem and seemed to have fun with it, making the result fit into the surroundings in such a way that it deceives the viewer as to its size and complexity. While conforming to the previously established theme for rustic architecture on the monument, Lium also established a central component for the development that landscape work and lesser structures could accentuate. The chateau has a high degree of integrity (both in structure and fabric), as does the surrounding designed landscape. [11]

B. Description of Exterior:

1. Overall dimensions: The main entry is on the first floor (or fourth, if counting the three basements) is on the building's south elevation along the road that separates the cave entrance from the hotel. Above it are two floors that contain guest rooms. The chateau's configuration precludes getting cubic dimensions, but the average height of the hotel is 95 feet, while the square footage of the first floor, first basement, and second basement has been measured to be 6670 feet. The dimensions of other levels range from 5610 feet on the second floor to 707 feet in the third basement, the latter figure largely being imposed by the narrowing of the gorge at the hotel's bottom level. The largest constraint on the third floor's 1914 feet is the tapering done to support the irregular roof.

2. Foundation: Reinforced concrete base enclosing the third basement. A rock facade hides the concrete below this level. The outer walls and floor of the second basement are concrete.

3. Walls: Shiplap siding sheathed with cedar bark. This gives the building a shaggy appearance like the other buildings on the monument.

4. Structural system, framing: The chateau has wood-frame construction with large interior post and beam supports. Interior posts are wood with the exception of one in the coffeeshop that was installed during the 1954 remodelling for patron circulation.

5. Porches, stoops, balconies, bulkheads: There are steel fire escape stairs and balconies on all upper story levels of the north and west elevations. For the most part, they replaced the original wooden stairways and verandas on this side of the building.

6. Chimneys: One main chimney with six flues is located on the northwest side of the building.

7. Openings:

a. Doorways and doors: The main entry is at road level on the south side and consists of two plain wooden doors with glass panels. A seven light transom is above the doors. Transoms over other doors in the chateau vary, ranging from six over the dining room doors to 14 over the cocktail lounge egress. Secondary access to the building is through this latter door and/or one that services the coffeeshop. On the west side of the chateau is a three-section door that services the third basement. Other doors on this side access the storage area and employee dining room in the second basement; first basement doors serve the kitchen and dining room. Other doors in the hotel open to fire escapes. All doors have plain surrounds except the main entry, which has a bark facade on three sides.

b. Windows and openings: A variety of wooden windows are used to pierce the chateau's walls. Patterns include eight-over-one double—hung sash, six—pane fixed, multi-paned casement, twenty-over-one fixed sash, and round—topped fixed sash beneath the upper gables. All windows have plain surrounds. Two louvered fenestrations perpendicular to the northeast-southwest roof axis were added during the installation of the chateau's sprinkler system in 1950. They are not sufficiently large enough to make this part of the roof a half-story.

8. Roof:

a. Shape, covering: The chateau has a steeply pitched, wood-shingled gable roof with intersecting cross—gables. Its roofline is broken by several shed-roofed dormers which, in turn, are pierced by steeply pitched gable-roofed dormers. The result is a highly irregular configuration with regard to how the rooflines of the three primary building sections meet and intersect each other's dormers.

b. Cornice, eaves: The roof's extended eaves are supported by unpeeled log brackets, exposed rafter tails, and plain fascia boards.

c. Dormers, cupolas, towers: On the south and northeast elevations of the building, two gable-roofed dormers intersect one shed dormer that runs along the second story. The gable dormers have peeled log brackets in them and are a subtle contrast to those under the eaves and in the end gables. On the northwest and southeast elevations are two parallel shed dormers that run along the second and third floors.

C. Description of Interior:

1. Floor plans: There are three basements below the first floor and two stories above it. At the bottom level is the third basement, a V-shaped section that contains the chateau's heating system. Above it are storage areas and a concession employee dining area in the second basement. Just below the road level is a first basement that contains the dining room/cocktail lounge, kitchen, a restroom, and coffeeshop. The main lobby, a registration counter, some offices, one restroom, and five guest rooms are on the first floor. The second and third floors are divided mostly into guest rooms, but some have been converted into quarters for concession staff. Guest rooms are of varying sizes, in part because some are suites, but also because of the limitations imposed by the chateau's configuration.

2. Stairways: The main staircase connects the first floor to the guest rooms on the upper floors and goes to the dining room/lounge located in the first basement. It is open and has rectangular oak planks for treads (highly polished originally and now varathaned) notched into peeled log stringers. The balustrades are madrone that has been left unmilled and show the deep, reddish brown color of the wood. The handrails are a lighter color and made of lodgepole pine.

3. Flooring: Ease of maintenance was the reason for carpeting the floor of the main lobby, which retains the original battleship linoleum. The hallways and floors of the upper three levels have likewise been covered by carpet, except for non—original tile in the bathrooms. In the first basement, the dining room's original maple tongue and groove floor was replaced with a plywood subfloor and asphalt tile after the 1964 flood. The original oak parquet floor in the coffeeshop was also replaced at this time with asphalt tile and a twelve inch high mopboard to hide the mud stains left by the flood debris.

4. Wall and ceiling finishes: On the walls, the most common finish is a redwood wainscoting that has an original type of pressed fiberboard, "Nu-Wood", above it and on the ceilings. The pattern of square ceiling panels of Nu-wood is broken in the hotel lobby where the overhead lights hang from a chain that is attached from the center of a Gothic diamond pattern. In the coffeeshop, the original knotty pine panelling has been retained, but in the dining room the original wainscoting was replaced by African cherry panelling after the flood. It was carried up to the ceiling because it was the best match to the original wainscoting and "Nu—wood" was not available.

5. Openings:

a. Doorways and doors: Interior doorways are typically plain, unpainted wood doors with a recessed panel. All have plain surrounds.

b. Windows: A large window on the stairway landing that connects the dining room with the lobby provides natural light, as do the windows on the west side of the lobby and the dining room below which overlook Cave overlook Cave Creek canyon. All windows have plain surrounds.

6. Decorative features: One of the building's most publicized features has been a basement conduit that allows part of Cave Creek to flow through the dining room. This was built in 1931 when the stream was rerouted at the cave entrance so that the chateau could be built in the gorge. The diversion allows water to go through the two trout pools and under the hotel before it rejoins the rest of Cave Creek further downstream.

Another notable feature is the lobby's freestanding fireplace that has two hearths, one on each side. It was built from stone quarried from the adjoining hillside when the roadway in front of the hotel was improved during 1931. An often overlooked feature of the fireplace is that it has a miniature cave on one side of it, while the opposite side has a stand for a model caveman that could be illuminated.

Other lobby features include the massive structural logs that serve as posts and beams. These appear to be hand joined by wooden pegs, but in actuality the motif is decorative and applied. Near them are ten circa 1925 Fred Kiser hand-colored photographs. Arts-and-crafts wrought iron sconces are attached to the posts, while hand-crafted lights hang from the ceiling and have the original hand—laced parchment shades. The furniture has a definite arts—and-crafts appearance, and is found throughout the building. Designed and built by a company in Monterey, California, it is made to appear hand—crafted and has one or more of the following features: a horseshoe emblem, wrought—iron hinges, leather straps, or a hand-painted floral design.

The coffeeshop is noted for its birch and maple counters that compliment the soda fountain. Stainless steel stools with red vinyl seats line the service area. Most patrons enter the coffeeshop from the courtyard, an area that had to be rebuilt after the 1964 flood.

PART III. SOURCES OF INFORMATION

A. Architectural Drawings:

1. Structural elements and details:

a. "Oregon Caves Chateau" by G.A. Lium, ca. 1931, six sheets [floor plans only], Concession Files, Oregon Caves Chateau.

b. "Floor Plans and Elevations for Oregon Caves Chateau" by Grand Rapids Store Equipment Company, Portland, ca. 1937, one sheet [coffeeshop plan], Concession Files, Oregon Caves Chateau.

c. "Kitchen Arrangement for Oregon Caves Resort, Oregon Caves, Oregon" by DeReamer, Kalbearer Hotel Supply Company, Portland, April 5, 1947, one sheet, Concession Files, Oregon Caves Chateau.

d. "Alterations to Coffeeshop, Chateau, Building No. 521, Oregon Caves National Monument, Spring 1954", and "Alterations Providing Addition of Cocktail Lounge, Chateau, Building No. 521, Oregon Caves National Monument, Summer 1954" no author, two sheets, Concession Files, Oregon Caves Chateau.

e. "Oregon Caves Chateau" by Paul Turner, September 1952, three sheets [sketch plan], Maintenance Division Files, Oregon Caves National Monument.

2. Landscape components:

a. "Stone Steps, Exit Trail" by Howard Buford, drawing no. 3003, November 14, 1934, one sheet, Interpretation Division Files, Oregon Caves National Monument.

b. "The Master Plan for the Oregon Caves National Monument" coordinated by the Branch of Plans and Design [drawn by Francis G. Lange], 1936, two sheets, Interpretation Division Files, Oregon Caves National Monument.

c. "Walk and Curb, New Chateau Area" by Francis G. Lange, drawing no. 2055A, January 25, 1938, one sheet, Maintenance Division Files, Oregon Caves National Monument.

d. "The Master Plan for the Oregon Caves National Monument" coordinated by the Branch of Plans and Design [drawn by Francis G. Lange], 1938, three sheets, Interpretation Division Files, Oregon Caves National Monument.

e. "Stone Walls, Chateau Area" by Francis G. Lange, drawing no. 2004, April 6, 1940, one sheet, Interpretation Division Files, Oregon Caves National Monument.

B. Historic views:

Numerous photographs have been taken of the chateau, especially during the first decade of its existence. Four sources provided all the photographs used in doing the documentation of the structure and its site.

1. Museum Collection, National Park Service, Oregon Caves National Monument.

2. Photograph Collection, Concession Files, Oregon Caves Chateau.

3. Oregon Caves File, Photograph Collection, Josephine County Historical Society, Grants Pass.

4. Inventory Sheets, National Park Service, Pacific Northwest Region, Cultural Resources Division, Seattle.

C. Interviews:

1. Francis G. Lange, September 12-14, 1988, Vacaville, California, resident landscape architect 1934-40. Interview by Stephen R. Mark.

2. George K. "Keith" Wells, August 15, 1982, Oregon Caves National Monument, civil engineer 1930-31. Interview by Ted Davis

D. Sources:

1. E.H. MacDaniels, Forest Supervisor, Siskiyou National Forest, to C.M. Granger, District Forester, April 9, 1923, Interpretation Division Files, Oregon Caves National Monument.

2. Grants Pass Courier, August 16, 1929, p. 1.

3. Portland Oregon Daily Journal, September 11, 1931.

4. U.S. Forest Service Special Use Permit, Union Creek Resort, January 1, 1922 [copy received by the Siskiyou National Forest on January 17], Interpretation Division Files, Oregon Caves National Monument.

5. E.H. MacDaniels to C.J. Buck, Assistant District Forester, January 19, 1922, Interpretation Division Files, Oregon Caves National Monument.

6. MacDaniels to Buck, April 9, 1923, op. cit.

8. C.J. Buck, Assistant District Forester, to J.H. Billingslea, Forest Supervisor, Siskiyou National Forest, October 2, 1929, Interpretation Division Files, Oregon Caves National Monument.

9. Mervin Mecklinburg, Archival Specialist, Oregon State University, to Steve Mark, Historian, Crater Lake National Park, August 14, 1989, History Files, Crater Lake National Park.

10. Oral history interview, September 13, 1988.

11. Much of the architectural documentation is based on a draft prepared in September 1988 by Gretchen Luxenberg, NPS Historian, Pacific Northwest Region, Cultural Resources Division, Seattle. She built upon previous work done by Laura Soulliere Harrison, who did the national historic landmark nomination for the chateau in August 1985. See Architecture in the Parks: National Historic Landmark Theme Study, pp. 383-395, (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1986).

E. Likely sources not yet investigated:

Additional information about Arthur L. Peck and his influence on setting the design precedent at Oregon Caves might be in his correspondence held at the Oregon State University Archives in Corvallis. More detail about the building history at the monument should be obtained by interviewing people who have long-term associations with Oregon Caves. Prominent examples are Harry Christianson and Rick Sabin, both of whom live in Grants Pass and have been connected with the concession operation.

PART IV. PROJECT INFORMATION

This documentation is part of a donated recording project that took place at the Oregon Caves National Monument and Crater Lake National Park during the summer of 1989. From June 5 to August 25, research and measured drawings for the project were completed by HABS Project Supervisor Kurt M. Klimt, Architecture Technician Belinda Sosa, and Landscape Technicians John Nicely and Michael Egan. Coordination of the project was done by the NPS regional Chief of Cultural Resources, Stephanie Toothman, and HABS Principal Architect Paul Dolinsky.

Prepared by:

Stephen R. Mark

Title:

Historian

Affiliation:

National Park Service

Crater Lake National Park

Date:

August 25, 1989

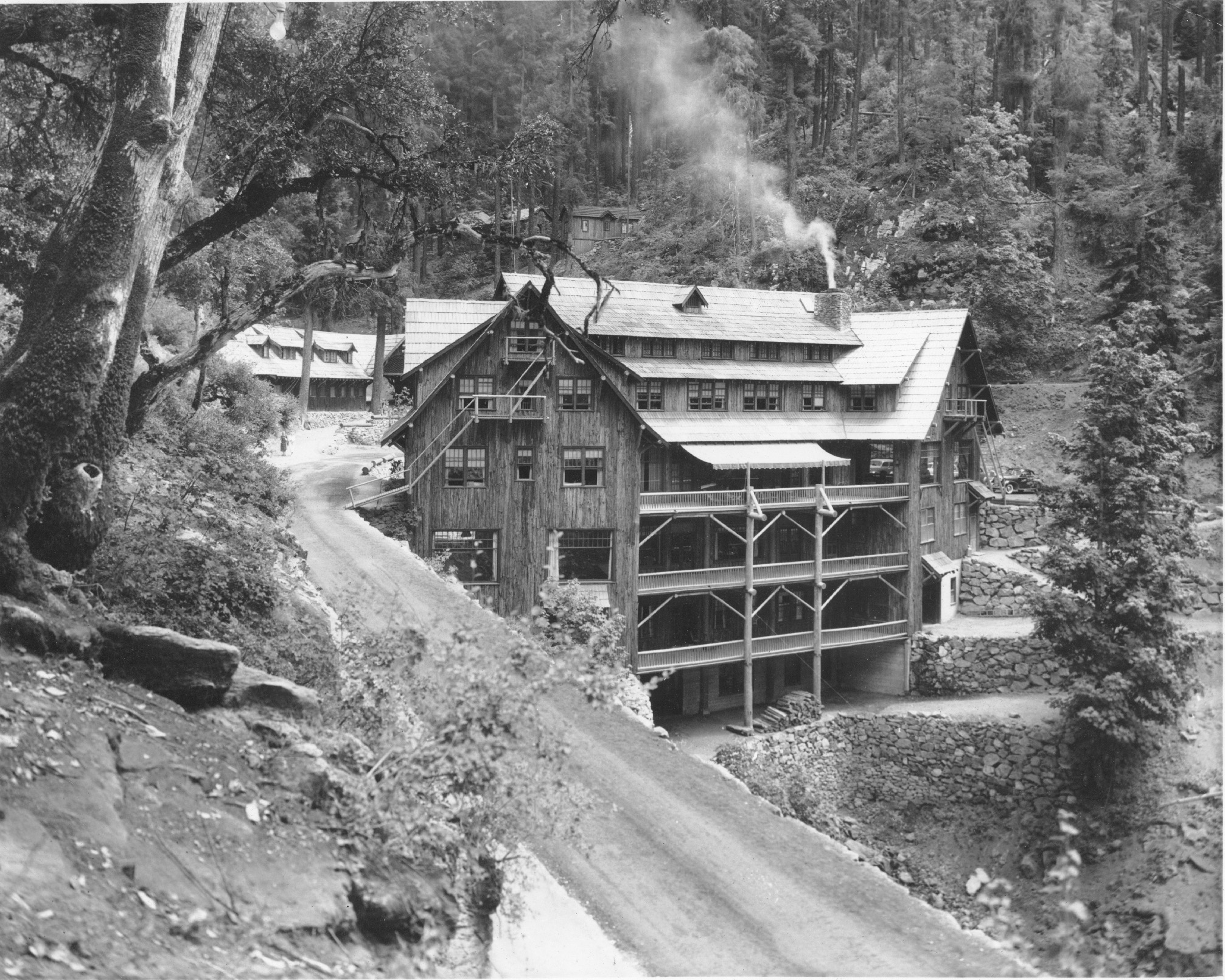

Oregon Caves Chateau (1938)

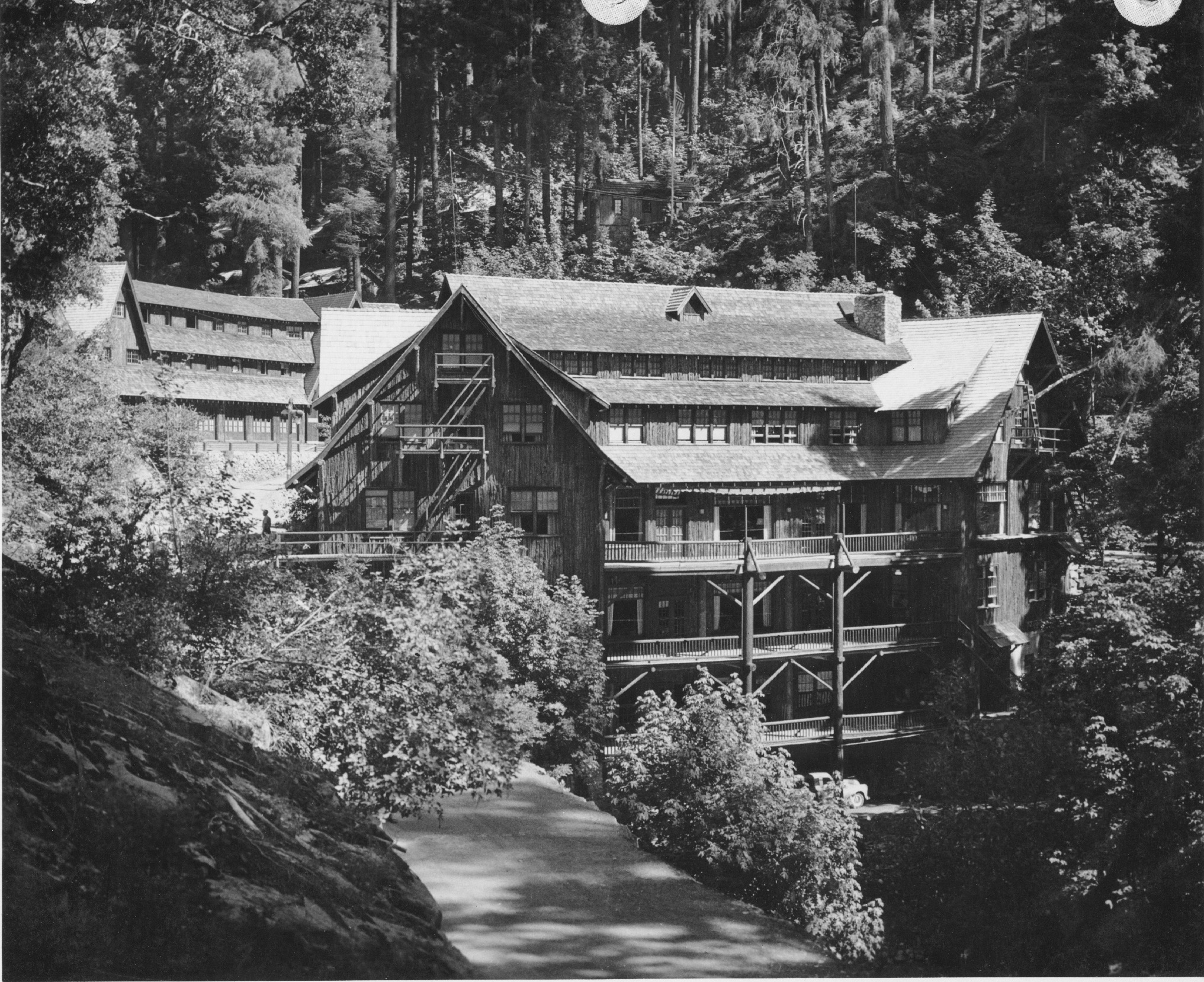

Oregon Caves Chateau (1946)

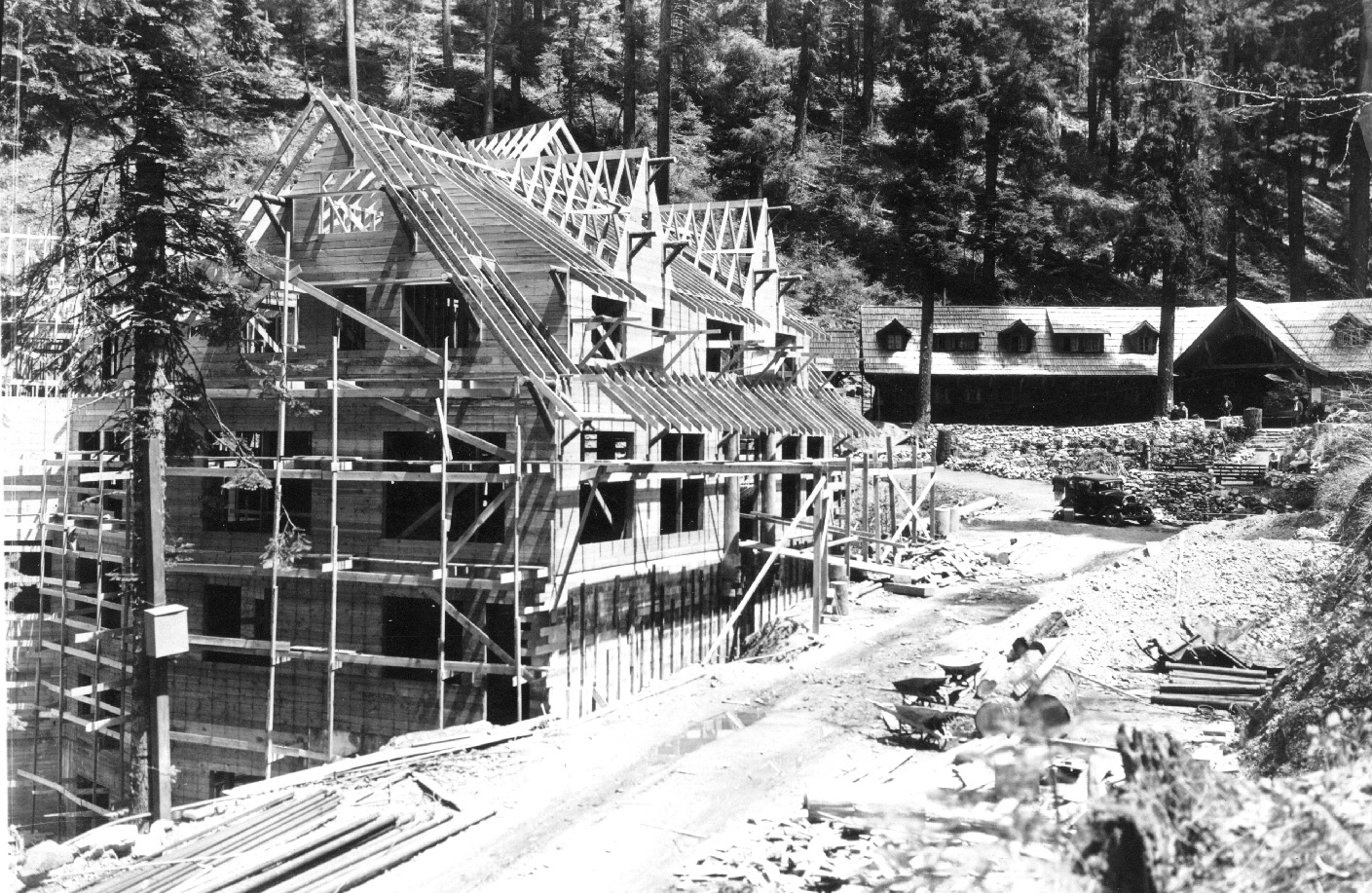

Oregon Caves Chateau (1933)

Oregon Caves Chateau

Oregon Caves Chateau

Oregon Caves Chateau

Oregon Caves Chateau (1949)

orca/habs/chateau.htm

Last Updated: 08-Nov-2016