|

Oregon Caves

Oregon Caves Chateau Historic Structures Report |

|

PART I

Site and Building History

Developmental History — Pre-Oregon Caves Company

The Oregon Caves have served as a popular attraction in southern Oregon since the 1870s. The first recorded cave entry was in 1874, when Elijah Davidson discovered the caves on a hunting trip. There are differing accounts of the discovery, but mostly in the finer details of the discovery. In the fall of 1874, Davidson had just killed a deer when his dog Bruno picked up a scent. Davidson instructed Bruno to follow the scent, and the dog raced up the hill and disappeared into a dark hole in the side of the mountain. Davidson heard the sounds of a fight within the cave, and in order to save his dog he entered the cave. He used matches to light his way initially, but soon ran out of light. He followed the stream out of the cave, and shortly thereafter his dog emerged from the cave.

Main entrance to the Oregon Caves. |

Davidson returned to the cave with the deer carcass and hung it outside the cave entrance. This lured a bear from the cave, and when Davidson returned a short while later the bear had eaten the deer and was sleeping nearby, where Davidson shot it. The killing of the bear, especially the timing, is the main discrepancy between different accounts of the story. The location of the bear when shot is also disputed.

After killing the bear, Davidson and members of his hunting party returned to explore the cave, using pine torches and matches. Davidson returned to the cave over the next few years many times, bringing small groups of family and friends with him. In early trips, stalactites were broken off to mark the route out of the cave. By 1877, exploration parties were using rope or lengths of string to mark the trail out of the cave. [1] 1877 also marked the discovery of the 110' exit. [2]

By 1880, news of the cave had spread throughout the Illinois valley. In that year two brothers, Homer and Ernest Harkness, took a squatter's claim at the main entrance to the caves. Exploration of the cave continued, and development around the mouth of the cave began. The caves were publicized in the Grants Pass Courier by Homer Harkness and Walter Burch in 1885, advertising that there was camping, good pasture, and "medicinal" waters at the cave. Harkness and Burch, from Leland, filed a mineral claim on the 160 acres surrounding the cave on May 19, 1885. Their intent was to construct a "trail or waggon [sic] road to said caves in the near future." [3] They were unable to acquire the land, however, because the land was unsurveyed. Burch later sued the Oregon Caves Company over the claim, insisting that his claim was valid under the Timber and Stone Act of 1878 (20 Stat. 89). However, a state judge dismissed the suit in 1925 in Josephine County Circuit Court because the Act of 1878 required that the land be surveyed.

Local entrepreneurs continued to develop the cave by removing formations that blocked passages. Work continued on developing trails to the cave, drawing more visitors. Advertising by W.G. Steel in his book The Mountains of Oregon and an expedition organized by the San Francisco Examiner, in 1889 and 1891, respectively, broadened interest in the cave. The Examiner expedition aroused interest in developing the cave as a resort, and the first proposal for a hotel at the site was made by A.J. Smith of San Diego in 1891. Acting as superintendent for the Oregon Caves Improvement Company, he proposed a 500 room hotel at the site, electric lighting for the cave, and a streetcar line from Grants Pass to the cave site. [4] These early proposals, however, amounted to little permanent development at the cave due to financial difficulties. Vandalism continued within the cave itself, as visitors broke off formations for souvenirs.

Mineral claims were halted not only by the lack of a survey in the area, but also by presidential intervention. President Roosevelt withdrew 10 million acres of forest land from settlement and claims in 1903, a result of land fraud trials in Oregon involving government timber. The Civil Sundry Act of 1891 allowed the President to set aside timber land from the unallocated public domain as forest reserves. The Southern Oregon Forest Reserve was established in 1903, withdrawing the cave area from settlement. This Forest Reserve was transferred to the Department of Agriculture from the General Land Office on February 1 1905, due to the difficulties the Department of the Interior had during the period of the land fraud investigations. The U.S. Forest Service was established under the Department of Agriculture on July 1 of that same year, with Gifford Pinchot as Chief Forester.

The USDA Forest Service then held control of the Oregon Caves area as a part of the Southern Oregon Forest Reserve. Mineral and settlement claims were forbidden by Roosevelt's withdrawal of the land. In 1906, the Siskiyou National Forest was established within the boundaries of the earlier Southern Oregon Forest Reserve. This allowed mineral entry and settlement under the Forest Service guidelines, but only under certain conditions. By this point, the cave area had experienced limited development and construction, including a small cabin built by the Examiner group, a camping area near the cave entrance, and blasting and obstruction removal within the cave itself, mostly by Burch and Harkness.

1906 saw the passage of a bill in the U.S. Congress that was critical in shaping the history of the caves. On June 8, 1906, Congress passed An Act for Preservation of American Antiquities, more commonly known as the Antiquities Act. This act allowed for the President to set aside as National Monuments "historic landmarks, historic and prehistoric structures, and other objects of historic or scientific interest that are situated upon lands owned or controlled by the Government of the United States." This act became the cornerstone of preservation within the federal government, preserving all types of resources. It allowed preservation advocates an easy way to meet their needs, resulting in a broad range of sites united in name but not in content.

The bill was important in that it allowed for the protection of areas to be preserved without a distinct purpose (as seen in the establishment of National Parks - the preservation of areas with exceptional natural beauty), growing to include areas that local and federal officials sought as national parks. However, the bill did not stipulate that the areas be funded, and all national parks required support and approval in Congress because they involved federal allocations. Instead of pushing for a bill to establish a national park, which would all be held up to the example of Yellowstone for natural significance, officials could lobby for the proclamation of a National Monument. This was much easier to achieve because it only required the signature of the President. However, these areas were not seen as resources of the importance of National Parks, a status that hindered the development of the National Monuments, especially following the establishment of the National Park Service in 1916.

The ambiguous language in the Antiquities Act allowed for a wide range of possibilities. It allowed special interest groups to gain protection for areas that federal agencies deemed unworthy of protection by other means. Many areas that could be protected under the Antiquities Act did not meet the amorphous standards for National Parks. President Roosevelt used the language of the act, especially the "scientific interest" clause, to establish monuments with a wide range of significance. The ambiguity in the act gave him vast latitude to create his own version of the boundaries of the monument category. There were limitations, however. National Monuments could only be established on federal land, including unallocated public domain, National Forests, and military reservations.

Most of the early National Monument proclamations established protection in areas that had previously been placed in temporary withdrawals. There was little argument about the suitability of reserving places already withdrawn from public exploitation, places which were predominantly protect the cave. [5] Associate Forester Overton W. Price responded, stating that the monument proclamation had been submitted to President Taft. On July 12, 1909, Taft signed Proclamation No. 876 (36 Stat. 2497), officially establishing the Oregon Caves National Monument. This 480 acre tract was protected from "any use of the land which interferes with its preservation". The monument fell under the jurisdiction of the Forest Service, as they controlled the surrounding Siskiyou National Forest. National Monument status was deemed appropriate not only for the potential scientific possibilities, but also because of the amount of vandalizing by visitors. The Forest Service also saw the establishment of the Monument as a way to engender local support for the Siskiyou National Forest, in addition to the possibility of federal appropriations to promote tourism within the region. The size restriction of 480 acres did not preclude timber harvesting in the surrounding forest, and was in accordance with the Antiquities Act requirement that the size of such reservations be limited to the smallest area compatible with the proper care and management of the objects to be protected.

About the time of the Monument's establishment, the Forest Service was receiving requests for permits and leases to develop the cave site. As early as 1908, the Forest Supervisor in Grants Pass received a request from G.O. Oium to develop electric lighting within the cave, make improvements in the circulation system within the cave, develop a guide service, and place tents for rent on the site. [6] Other early attempts to secure a Special Use Permit by local entrepreneurs to establish a guide service and provide lighting within the caves were made, but the Forest Service did not initially act on the requests.

The Forest Service was hesitant to act on these requests because it was still attempting to define its own role at the Monument. The discussion involved the Forest Service's ability to let contracts on government lands, their position with respect to the cave guide service, control over the cave entrance, and other policing activities. The guard issue was settled in the spring of 1911. A guard was provided primarily as a protection against vandalism with a secondary purpose of providing a guide service through the cave. [7]

The issue of permits for construction on National Monument land was debated within the Forest Service. In 1912, a USDA solicitor stated that the Forest Service did not have the authority to issue a permit for the development of the Monument as a resort facility. As a National Park, however, the Oregon Caves would be allowed development under a concessionaire contract. This spurred an early attempt to garner National Park status for the Oregon Caves, led by the Game and Fish Protective Association, a local group pushing for the creation of a 200,000 acre park to facilitate hotel and road building. This attempt failed, even though two separate bills were introduced in Congress to try to establish a National Park at the site.

The passage of the Term Occupancy Act on March 4, 1915 allowed the possibility of concessionaires at the Monument. This bill permitted the Forest Service to lease land for the construction of hotels, summer homes, concessions, and other recreational uses. Local entrepreneurs were again encouraged by this act, but the Forest Service was reluctant to grant a lease to most of the development schemes because the applicants did not possess sufficient capital to make worthwhile improvements. The Secretary of Agriculture stated the official view in the statement "it is our policy to encourage the development of recreation areas, like the Oregon Caves, in every way possible." [8] The lack of a road into the Monument was also a concern for the Forest Service, as the ability to draw large numbers of visitors would be necessary before a long-term permit was issued.

Even though the Forest Service was now allowed to make long-term concession contracts, the agency remained cautious about development at the cave site. Planning concerns were of high importance to the District Forester from Region 6, headquartered in Portland. Assistant District Forester C.J. Buck summarized the agency's agenda and process in a letter to Siskiyou National Forest Supervisor MacDaniels in February of 1920. Buck wrote:

I think there is no doubt but that the Forest Service is obligated to undertake a plan of development at the caves. It is also absolutely certain that our responsibility cannot be redeemed unless the kind of improvements, location and landscaping of the grounds are worked out with great care. A recreation plan for the development of this place is absolutely necessary... Personally, I do not feel that proper development can be had unless considerable work on the ground and thought is given the matter... The matters I am particularly concerned about are outside the Caves, such as planning the location of the road, camp grounds, hotel site, parking grounds, guide's cabin and other improvements. The area of suitable land is so limited that considerable foresight must be exercised in placing the improvements where the effect will not be displeasing... As a fundamental part of that plan, I would put the location of the road. [9]

The Forest Service did have an obvious desire to develop the site, but without a road their efforts would be fruitless, as only 1800 visitors a year were making the arduous trip to the cave.

The Oregon Caves Highway, soon after completion. |

The issue of the construction of a road to the Monument was paramount in the Forest Service's consideration of issuing long-term permits for development. An auto road had reached nearby Holland in 1912, fifteen miles from the cave. California's announcement of an appropriation to construct a highway from Crescent City to the Oregon border furthered the interest in the development of the project, as even more visitors could reach the site via the planned Redwood Highway. The contract for the road construction to the caves was let in 1921, with a time limit of 180 working days for its completion. Work started in August of that year, with a major effort in clearing brush and trees from the right-of-way. It was estimated that over a million board feet of timber and a "correspondingly large" amount of brush would have to be removed. [10] The work proceeded quickly, and by October the road was 1/3 complete. [11] The 11.7 mile road was officially opened on June 27, 1922, at a final cost of $295,000. In terms of visitor numbers, the new road was quickly a success. Visitation to the Monument jumped from about 1900 people in 1921 to over 10,000 in 1922.

At this time, a tent camp was being run at the caves by McIlveen under the first contract granted by the Forest Service on the site. Food was also provided for visitors at the cave. The increase in visitation prompted the Forest Service to draft the first development plan for the area. This included the development of a number of small cottages at the confluence of Grayback and Sucker creeks for visitor accommodation on land recently transferred from the General Land Office to the Forest Service. The development at the Monument included a proposed 25 x 35 foot log house to be built about 700 feet down Cave Creek from the main entrance to the cave and a number of small cottages near this hotel. The proposed Union Creek development near Crater Lake was taken as the model for the development at the Monument. Buck envisioned a ranger cabin and picnic tables in the area near the cave entrance. The Forest Service was clear on the style of the development from the start. A Special Use Permit drafted in 1922 includes a condition that "All buildings and structures shall be of the same general style and of an accepted type of rustic architecture." [12]

Oregon Caves Company Development

The tent camp above the Chalet. |

At the time of the completion of the Caves Highway (now Oregon 46) in 1922, McIlveen was operating a tent camp under a Special Use Permit from the Forest Service at the caves. A group of local businessmen from Grants Pass saw the caves, Monument, and general area as having a high potential for development, and in 1923 filed an application for another permit. The District Forester, George Cecil, had been working with the group for at least a year on the development of the application, and felt that the group was comprised of "responsible business men of Grants Pass, none of great wealth, but all sound, public-spirited citizens, whose names are more than sufficient to back paper of this kind." [13] The District Office in Portland sent news to Forest Supervisor MacDaniels on March 16 that the term lease had been approved. [14]

The Special Use Permit granted to the newly established Oregon Caves Company essentially involved three critical components. First, the OCC was to establish a guide service for the cave, including the availability of coveralls and appropriate light sources. Second, the OCC would be allowed to construct a "permanent guide headquarters station building" immediately, containing an office and registry room, ladies' dressing room, public rest room, and an optional lunch room or kitchen. These requirements could be met through either one or two buildings on the Monument, with Forest Service approval of the design prior to construction. The quality of the building(s) was kept to a relatively high level, with the stipulation that the construction cost a minimum of $2,000. [15] The third component of the application was a proposed resort development at the mouth of Grayback creek.

The Grayback Creek component of the permit contained a set of minimum requirements, agreed upon by the Oregon Caves Company and the Forest Service. The OCC was to develop, by June 15 of 1923, a tent camp including a dining facility and kitchen to accommodate 30 overnight visitors. A permanent store with camping supplies would also be constructed by this same date. Within a year of that, the company agreed to complete a main resort building with a lobby, dining room, and kitchen to accommodate 60 people, construct a pressure water system, and build outdoor restroom facilities. By July of 1925, the company was required to accommodate 30 more people in new "cottages" or in wings attached to existing structures. By July of 1926, the OCC was required to develop cottages, wings, or other permanent structures to accommodate a total of 60 visitors. The original concession development at the Oregon Caves was to be a split between the resort development at the Grayback Creek site (8 miles from the cave) and the construction of limited facilities on the Monument. [16]

In order to properly formulate a development plan, Arthur L. Peck of the Oregon Agricultural College in Corvallis (now Oregon State University) was persuaded to visit the area and advise the Forest Service and the Oregon Caves Company on how to lay out the development at both sites. Peck, a professor of landscape architecture at the college, advised the company to make use of a flat area within the ravine near the cave entrance, about 100 feet to the east of the entrance itself. Peck's plan was to introduce a "good sized building on the terrace, where Mr. McIlveen's mess tent was last year, with a porch from which a view of the entire lower valley could be obtained." [17] The porch was intended to extend "beyond the house so that it would include the spring that was opened on this terrace, and this porch would form an entrance to the path to the Caves and also to the trail up the gulch leading to the upper entrance. Upon this trail there would be one or more small buildings as on an irregular street. There would not be many of these, as there is no need for them, the dining-room and office being in the large building." [18]

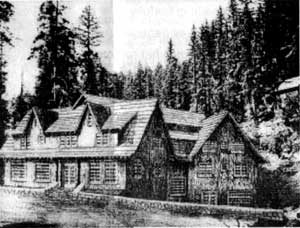

The original Chalet and evening bonfire. |

Peck, in agreement with the 1922 Forest Service plan for the monument, decided on an architectural style for the development around the cave entrance. His idea was that the buildings should respond to the local climate, which involves heavy snowfall during the winter months. An "Alpine type" of structure was needed to serve this end, but it also suited the particular landscape of the site. The notion of the Chalet was born, and to answer additional landscape aesthetic concerns Peck decided the building should be finished with a cladding of Port Orford cedar bark or sugar pine shakes. Either of these options would quickly weather to a silver gray or reddish brown, blending in with the colors of the surrounding landscape. The architectural style was chosen chiefly because of its suitability to high elevations and the surrounding mountains and big timber. The picturesque and distinctive style contributed to, instead of distracting from, the landscape.

The new building, the Chalet, was constructed in 1923. This was the first permanent construction by the Oregon Caves Company at the Monument, containing a lunchroom, cave tour registration Oregon Caves Chateau office, restrooms, and seven rooms to accommodate visitors and employees. The massing of the 1-1/2 story Chalet was primarily located to the north of the "porch" that evolved into a breezeway separating the two portions of the building at the ground level. The breezeway, or porch spoken of by Peck, spanned the base of the ravine and linked the larger northern portion of the building with the smaller southern portion.

The guest cottages. |

The original Chalet was replaced with a new building during 1941-1942. The new structure retained the same general massing locations and design ideals of the original, but was set back ten feet further from the road to facilitate pedestrian circulation. Gust Lium, an architect and contractor from Grants Pass, was responsible for most of the design. The new Chalet was larger than the original, yet it still fit into the confined and rugged topography of the Monument. Lium took the functions contained in the original structure and answered the demands for a new building on the same site with expanded facilities, showing his adaptation to the limits imposed by a confined site. The building cost $25,000 to construct, exceeding the initial estimates by about $8,000. However, the Oregon Caves Company was eager to finish construction before wartime inflation took effect in the area. This 1942 version of the Chalet exists today, the second permanent building to occupy the same site. It continues to play its traditional role as an important facilitator of the visitor experience at the monument, and is the focal point for day use visitors to the Oregon Caves.

The concessionaire's next development at the Monument was the construction of a series of guest cottages in the ravine east of the Chalet. These seven cottages were also designed and built by Gust Lium in 1926, the same year that the Redwood Highway opened between Crescent City, California and Grants Pass. The cottages were sited above the Chalet and a nursery ("Kiddy Kave") just to the east of the Chalet, with short, steep, switchback trails connecting each cabin to the main trail. The tent cabins employed by McIlveen under his permit were still in the area as well, creating a mixture of structures in the gulch. The cottages were all laid out with the same floor plan, yet the exterior of each was distinct through subtle design changes such as the addition of small dormers in varying configurations and varied entrance details. The cabins held to Peck's basic design ideal of the development at the Monument, with Port Orford cedar siding and a rustic exterior appearance.

The guest cottages, looking down toward the Chalet. |

This development was closely followed the next year by the construction of a guide dormitory, north of the Chalet and set up on the hillside above the road. As originally built, the dormitory had only its vertical cedar bark cladding as a decorative feature. Like the Chalet and cottages, the dormitory was designed and built by Lium. It remains at the site today, a two story rectangular building somewhat hidden from view by plant growth. The placement of the dormitory was contrary to Peck's original decision to site the building west of the cave entrance.

By the middle of 1927, the resort at the Monument could accommodate about 56 visitors, plus the concession staff of about 20. [19] The money spent on the development at the cave site precluded any development of the Grayback Creek area, which was originally to be the main focus of resort development. The financial expense and attention to the day-to-day operation of the concession at the Oregon Caves "made Mr. Sabin (the manager of the resort, and a founding member of the OCC) very doubtful about whether they want to do anything with Grayback." [20] As early as the fall of 1924, it was fairly obvious to the Forest Service that the company was planning to abandon the permit for development at the Grayback site. The original Forest Service plan for development of the caves featured Grayback as the main resort, with the area immediately surrounding the caves serving as a subsidiary development. The concessionaire chose to develop the cave site first, and the plan to develop a resort at a distance away from the caves on government lands never came to fruition.

Oregon Caves Chateau Construction

Only one year after the completion of the Chalet, the Oregon Caves Company began thinking of further development of accommodations at the Monument. Fred Cleator, a forester who essentially functioned as a landscape architect and recreation planner for the Forest Service, reported in July of 1927 that the concessionaire was considering the "possibility of a large new hotel unit costing about $100,000 with dining room on lower level to be traversed by Caves Creek inside." [21] The Oregon Caves Company already had accommodations for 20 people in 10 tent houses, 42 people in seven double cottages, and 25 people in the Chalet and guide dormitory. [22] However, due to the rising number of visitors, the company sought to increase their capacity. The needs expressed to the Forest Service by George Sabin, manager of the resort, were "an ample lobby, increased dining room and kitchen facilities, and heated rooms." [23] The opinion of the company stockholders was that the term for the Special Use Permit granted by the Forest Service should be increased to twenty years at a minimum in order to justify the expense of construction by the concessionaire. The cost estimate for the new building was reduced to $50,000 from the earlier estimate of $100,000, yet the company still wanted some measure of stability and control over the development through a longer term permit.

Professor Peck was brought back to the Monument again to assist in the planning of the proposed hotel. Peck argued that the site at the head of the gulch formed by Cave Creek would be the ideal location at the site, because a hotel building at that location would fit well with existing and future developments. He proposed that the head of the draw be filled in to form a court, as the new building would serve as "the hub of all further improvements." [24] The new construction would also allow for some circulation improvement at the road level, which would be widened by five feet. [25] The new structure would also be an aesthetic improvement at the site because it would allow the tent cabins to be removed. These were initially a temporary arrangement, and Peck found them intrusive and disapproved of their location and existence. [26] They were allowed to remain by the Forest Service, but only if the new hotel was under construction by the 1930 season. They could be used only until the completion of the hotel, according to the agency.

By the summer of 1930, Mr. Sabin and the Oregon Caves Company were anxiously awaiting word on the approval of their plan to build. They wanted to get materials to the site before the heavy rains set in, but a decision was not officially made by the Forest Service until June 1 of 1931, when a Term Permit for 20 years was granted to the Oregon Caves Company allowing the construction.

Sabin, Peck, and Lium met with the Regional Forester in Portland about the proposed hotel design. The Forest Supervisor, J.H. Billingslea, felt that the plan was "unusually well adapted to the location, and conceived only after very careful planning." [27] Like the earlier cottages and Chalet, the hotel was to be built in the Rustic style. The style was dictated by the Special Use Permit, which stated "all buildings shall be of the same general style and of an accepted type of rustic architecture."

Lium's perspective drawing of the Chateau from the Morning Oregonian. |

Gust Lium's rustic design for the Chateau appeared as a perspective drawing in The Morning Oregonian on August 7, 1931 and the Medford Mall Tribune on August 18, 1932. It fit within the ideals of the style, using local materials in a structure in harmony with the site. The building's massing, proportion, and siting within the natural context were critical to the style, and the Chateau proved to be exemplary in all aspects. As a representative of the rustic style, the richness of texture in the exterior treatment and a juxtaposition of shapes yields a refined aesthetic that is both decorative and functional. The steeply pitched roof, Port Orford cedar bark cladding, and varied intersecting roof forms give the building a rugged appearance that blends with the mountainous site, complementing the surrounding landscape. The location of the building is also critical, for even though it is a 28,000 square foot structure its location at the head of the ravine and its six stories allow it to be less intrusive, as the lower three floors are below the level of the road.

The use of local materials is also an ideal of the rustic style, and the Chateau succeeds gracefully in this aspect. This was especially important at this somewhat remote site. The stone for the fireplace was taken from the nearby hillside, and the lumber used was cut in the middle of Sucker Creek. From there it was trucked to the Villair and Anderson Mill on the Caves Highway at Milepost 14, were it was cut and trucked to the site. The cedar bark was obtained locally as well, taken from a railroad tie cutting operation on Grayback Creek upstream of the Grayback Camp.

Construction photo showing the concrete forms. |

Lium was a builder and architect (not formally trained) from Grants Pass, arriving in that town in 1923. He was a prolific local builder, completing over 50 houses in the Grants Pass area and a number of commercial and institutional structures. He also completed many projects for the Forest Service throughout the Siskiyou National Forest and six Rivers Forest. He was a leader of CCC construction crews, completing most of the wooden structures at Patrick's Creek campground and possibly some of the rock walls in the area. He was also remembered for his construction of the U.S. National Bank Building, a marble faced structure that was torn down in the early 1960's in Grants Pass. The building was solidly built and hard to demolish, a trademark of Lium's construction. He gained a reputation for constructing buildings that were built to last, regardless of style or setting. Lium was involved in the construction of the Chateau from the start, serving as both designer and contractor.

The Oregon Cavemen hard at work on the Chateau. |

Work on the Chateau began in September of 1931. Lium utilized a small crew for the construction, which was delayed due to the Depression and the negotiation with the Forest Service of a longer term permit. Lium's crew was usually less than 20 men, yet the construction was complete by May of 1934. This fact, taken in conjunction with the Oregon Caves Company's financial troubles during 1932 and 1933, reveal Lium's management skills and construction ability. The company was allowed to sell $25,000 worth of stock to help finance the construction of the hotel, but had difficulty locating investors. The Oregon Caves Company's finances were such that they had a hard time paying the fee for their term permit, choosing instead to place all free capital into the construction. Sabin wrote to the Assistant Regional Forester in March of 1934 that "even under these difficulties, we have steadfastly held to a determination, not to cheapen the finished product in order to complete" the construction. [28]

The Chateau just prior to completion. Note that the peeled log and steel fire escapes have not been installed. |

When completed, the new Chateau was praised both locally and regionally. Lium's skill at adapting the many requirements of the large structure to a confined site set the building apart, and the rustic character of the building fit within the Forest Service development scheme for the Monument. It became the showcase structure for the Monument, a hub of activity for both day visitors and overnight guests. The building officially opened May 12, 1934. One newspaper account of the newly opened structure commented

The new Chateau, unquestionably responsible for the major part of business increase at Oregon Caves, is deserving of more than casual examination, for several reasons: Native materials were used in all places possible, which employment has resulted in a building entirely in harmony with its surroundings. [29]

Another regional publication described the Chateau in the following way: "Successful effort has been made in the construction of the Chateau, both without and within the building, to keep it in harmony with the rugged wildness of the section, and yet provide a comfort unexcelled by metropolitan hostelries." [30] George Sabin, the manager of the new hotel, commented that "it's unique, and something different. It's constructed for the place in which it stands, and there is comfort everywhere." [31]

Post-Chateau Development by the National Park Service

Shortly after the completion of the Chateau, the Oregon Caves National Monument received a change in administration. It was transferred from Forest Service jurisdiction to the National Park Service by an Executive Order issued on April 1, 1934. The transfer was to officially take effect on October 10 of that year, but NPS administration of the Monument may have begun by August 10. The order transferred 16 National Monuments administered by the Forest Service to the NPS, all in the western states. Each retained its status as a National Monument, yet the scale and features (of natural or scientific interest) varied greatly. The press release announcing the transfer from the Department of Agriculture to the Department of the Interior stated that "the functions of administering these areas for national monument purposes was transferred to the National Park Service of this Department (Interior), and that office is prepared to assume jurisdiction at once." [32]

The National Park Service admired the development at the Monument by the concessionaire, especially the rustic character of their buildings. As a result, the NPS worked closely with the Oregon Caves Company over the next eight seasons in their development of the site. The NPS utilized Civilian Conservation Corps crews from Camp Oregon Caves, located at the Grayback site that was once to have been the concessionaire's main resort facility. The NPS intention was to make all new work harmonize with structures already in place at the caves, and through its planning process the CCC projects were coordinated with the concessionaire's improvements. The NPS process was aimed at obtaining a workable consensus from a wide variety of reviewers through comprehensive site planning and the preparation of master plans for each site. These plans were critical to the agency as it tried to obtain funding for CCC and other budget requests, and the master plan supplied a rationale and justification for each project.

The Ranger Residence in 1999. |

The NPS used a systematic development process, blending architecture with natural features and placing equal emphasis on each. At the time of the transfer to the NPS, the Monument contained a wide variety of structures, each designed for a specific purpose and built in the rustic style, the favored style of the agency during this period. The style was adapted regionally by designers in the Pacific Northwest, and the regional interpretation of the rustic style came to be termed "Cascadian". The stylistic moves by Lium and the Oregon Caves Company in their construction is perhaps the primary reason that the NPS admired the development at the Monument. The NPS took jurisdiction over a monument with a great number of structures, including the Chalet, guest cottages, Chateau, a rustic service station constructed in 1931, "Kiddy Kave" (the daycare facility), a powerhouse for the cave lighting system, the guide dormitory, and a guide shack near the entrance to the cave.

The NPS continued to develop the site to suit their particular needs. A ranger residence was constructed by the NPS using CCC labor in 1935-1936 on the hill above the guest cottages to the east of the Chalet. The building was designed by Francis Lange, the Resident Landscape Architect at Crater Lake National Park. His original design utilized Port Orford cedar bark cladding, laid horizontally instead of vertically. Sabin argued that this detail would not fit within the established design precedents at the monument, but also that the building would not shed water effectively. The siding was changed to run vertically, matching the other main structures at the monument. As the first government structure at the Monument, the NPS realized that its appearance should blend with the development by the concessionaire. The building achieved this aim. A checking and comfort station was also constructed by the NPS in the main parking lot, again employing the rustic style. The structure was placed at the road into the caves area, so that the NPS could achieve a measure of control over the one lane road to the cave area. The building was virtually the last CCC project at Oregon caves, completed in June of 1941. The combination of administrative and restroom functions in such a small building made the checking and comfort station unique within the National Park system.

General Physical Description

The Chateau sits on a reinforced concrete foundation in the head of the canyon formed by Caves Creek. The building site was blasted to clear a large enough site. The first floor, containing the boiler room and workshop, is smaller in scale than the floors above, matching the topography of the site. Its walls and floor are bare concrete that taper inward, creating a narrower space at the east end of the room than the west. A hole has been cut high in the north wall of this room, providing access under the north wing of the building. The south wall has an opening cut for the boiler exhaust vent that runs under the second floor to the base of the chimney. The west wall is penetrated by two windows and a double door providing access to the small exterior terrace. The ceiling is also formed of concrete, with reinforced beams as an integral part of the structure.

The second floor houses storage areas, limited employee housing, the employee dining room, and large refrigerators and freezers. This level is more expansive than the first, widening to fill the entire width of the valley head inside the road. The floors and exterior walls are constructed of reinforced concrete. The post and beam structural system begins at this level, resting on the exterior walls of the first floor and four columns placed in the middle of the space below. The base of the marble chimney is visible at this level, appearing as a large, stuccoed, rectangular masonry mass in the south wing. Openings on this floor are concentrated on the west side, with a series of double-hung windows in the employee dining room and employee quarters. A double swinging door is present at the west end of the south wing, providing access to an exterior terrace. One opening is present at the east side of the south wing that has been boarded over. The internal walls of this level are framed conventionally with dimensional lumber, and the north wall of the north wing has a wood frame wall running its entire length covering the exterior concrete wall. A dogleg stair in the center of the floor at the west side leads up into the dining room.

The third floor has a combination of structural systems. The exterior walls on the north and south sides are concrete, with the east and west walls making the transition from concrete to wood. The kitchen, dining room, coffee shop, and lounge/bar area are contained in this floor, as well as a dumbwaiter to the second floor, men's restroom, and the conduit containing the diversion of Caves Creek that runs through the space from east to west, a signature element of the building. The dining room and lounge areas are a single open space supported by the wooden post and beam structural system. The kitchen and dining room are separated by light wood framed walls, with two doors between the rooms. The kitchen is separated from the coffee shop by the fireplace mass and a freezer. Circulation between these rooms is achieved through a set of double doors. Exterior penetrations include three doors to the west, two to the east leading to the pond and courtyard, and a series of windows on each of these sides. The windows at this level are primarily large fixed windows with rows of smaller lites above the large pane. The main vertical circulation for guests starts at this level with a large staircase leading up to the lobby level.

The fourth floor, containing the lobby, office, front desk, and five guest rooms is entirely wood framed with either heavy timber or dimensional lumber. The lobby consumes most of the south wing and center sections of the building, with the office and front desk at the east end of the south wing. The guest rooms are located in the north wing, and a women's restroom is present in the northwest corner of the central trapezoidal section. The main entrance to the structure is located on the south side of the southern wing. The lobby windows are primarily large fixed panes with smaller lites across the top, similar to those in the dining room. The office windows and windows in the guest rooms are primarily double hung wood windows. The interior walls of the guest rooms and the partitions separating the office from the lobby are light wood framed with dimensional lumber, as are the exterior walls. The lobby and stair area contains the heavy timber system, supporting the floors above. The post and beam system ends at the ceiling of this level, and the floors above are constructed entirely of dimensional lumber.

The fifth floor is accessed from the main staircase that starts in the dining room and continues up through the lobby. The staircase is constructed with peeled log stringers supporting oak treads and a madrone and fir handrail. The floor contains eight single guest rooms and three suites composed of two adjoining rooms. Double hung windows are the primary fenestration, and two fire doors lead out from the west end of both the north and south wings onto the steel fire escapes. This level is the last full size floor in the building, as the roof shape constricts the size of the top floor.

The sixth floor, the top floor of the building, is reached via a stair in the south end of the fifth floor hallway. The floor contains two guest suites and seven individual rooms, although only five are in use for this purpose. The fenestration at this level is a combination of double hung and casement windows, with two doors leading out to the fire escape in the two unused guest rooms. Access to the attic is available through two hatches in the ceiling of the hallway at this level, and the lower attics are accessible through doors at the ends of the hallway and through access panels in the bath rooms of the south wing.

The roof is covered with cedar shingles, and has its own sprinkler system. It is formed by a variety of intersecting roof shapes, including a main gable with cross gables at the north and south wings, shed roof projections at the sixth floor, and a few small dormers. An access hatch is located just above the chimney, which is exposed marble with six clay tile flues. The valleys are open, containing crimped flashing. The rafter tails are visible at the eaves, and log brackets support the gable ends. The overhangs are large, and the building does not have a gutter system. A painted verge board is present at the gable ends.

The exterior walls are sheathed with shiplap covered by building paper. Port Orford cedar bark is the primary exterior cladding, and is nailed to the sheathing. Openings at windows and doors possess simple surrounds, and all windows have weathered wood sills. A steel catwalk and fire escape system are present on the west façade, lag bolted to the building. The bottom two floors on the west side are the only ones lacking the Port Orford cedar bark siding, and are painted concrete.

Chronology of Alteration

In the past sixty-five years since the completion of the Chateau, the building has undergone minimal changes and alterations. The integrity of the historic fabric, inside and outside the building, has been kept at a high level by the Oregon Caves Company. The concessionaire is responsible for the maintenance of the structure and all areas within five feet of the building. The structure's National Historic Landmark designation in 1987 by the Secretary of the Interior proves that the structure retains a high level of integrity in its fabric and even furnishings.

The earliest alteration was the addition of the rooftop sprinkler system, completed in 1934. Its purpose was to wet the roof down each evening, as required, before the campfire program. A large bonfire was constructed every night in a flat area between the cave entrance and the Chalet, and as a precaution against fire the sprinkler system was installed. The roof sprinkler system was presumably connected to the existing network of fire hose plumbing, which was present at all floors.

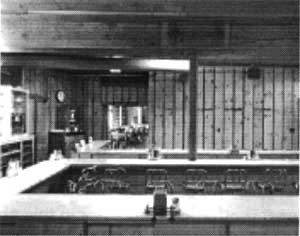

The original Coffee Shop. |

To complement the meal service in the dining room and Chalet, the Chateau was altered in 1937 by the addition of a coffee shop in the east end of the south wing. The space was originally used as storage, but was renovated to serve the new purpose. The plans were done by the Grand Rapids Store Equipment Company of Portland, and included a soda fountain on the east wall, knotty pine wall paneling, a parquet floor, birch and maple counters and shelves, and bright steel stools with red leather upholstery. This area could seat 23 patrons.

That same year, 1937, a generator was added in the boiler room on the first floor for emergency power. A generator still fills this spot under the windows on the west wall, and may be the original.

The Chateau's heat system was, and remains, a hot water radiator system. In 1946 an oil burner and 3000 gallon holding tank were installed to meet the demand from this structure and the Chalet, which was also heated by the same plant after its reconstruction in 1942. The availability of wood was another critical factor in this shift, as down wood for the boiler was becoming increasingly hard to find in the immediate area. This boiler is still in use today, and 1998 the firebox was replaced.

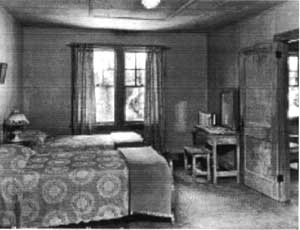

Typical Chateau guest rooms before... |

...and after the sprinkler. |

Perhaps the most significant alteration to the Chateau in terms of its interior appearance was the addition of a fire sprinkler system in 1950. This system runs through the inhabitable spaces in the Chateau, instead of through wall and ceiling spaces. The visual intrusion into the guest rooms is the greatest impact of this alteration, with some rooms containing four inch mains and other feeder lines branching out from these. The system itself is nearly historic by the Secretary of the Interior's age standards, but was installed in a less than sensitive fashion. The sprinkler system was modified and added to in 1961 as well, but the extent of the work involved during this period is unclear. The entire system received new sprinkler heads during the off-season early in 1999, as required by code.

About the same time the interior sprinkler system was installed, a series of fire doors was also added. These doors are present on the fourth and fifth floors. At the fourth floor, the door is located in the north wing in the hallway that is raised above the level of the lobby. The fifth floor doors are located to each side of the main staircase, leading into hallways running to the north and south. The doors themselves are steel, built into walls spanning between the two original walls at each location. The new walls are clad with a fiberboard product that does not match the historic Nu-wood panels.

Coffee Shop after 1954 remodel. Note the steel post. |

In 1954, the Oregon Caves Company remodeled the 1937 coffee shop. The space was enlarged by the removal of a kitchen restroom and relocation of the stairs to the second floor, which were moved under the main stairway from the dining room to the lobby. The capacity was increased from the original 23 seats to 45 through a new counter design that weaves through the space. The heavy timber column in the center of the room was removed and replaced with a steel post to facilitate circulation in the tight area between the stools. The interior finishes remained the same, and the stools retained their red leather seats and bright steel finish. The original double hung window to the north of the door leading out to the pond was increased in size and replaced with a large fixed window, matching the one on the south side of the door.

The front desk after alteration. |

A ramp was built from the kitchen to the second floor storage rooms in 1954 as well. This exterior alteration allowed employees to access the supplies below more easily. The front reception desk in the lobby was also changed about this time to allow for a display section and increased space at the desk.

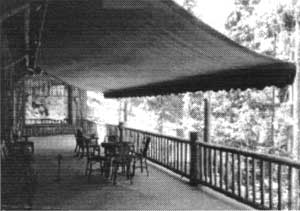

Historic view of the veranda. |

The largest exterior alteration to the Chateau during its existence occurred in 1958. Historically, wooden verandas were located on the west side of the structure, spanning from the north wing to the south along the western edge of the center section of the building. These verandas allowed visitors to the Chateau to relax and take in the view of the valley from either the third or fourth floor level. The log structure was a handsome component of the original building. It was removed in 1958, after the cumulative effect of overloading by snow caused the veranda to be condemned. The concessionaire elected to replace the wood structure with a series of steel catwalks bolted to the side of the building. The visual impact of the catwalks is minor, but the building lacks the original character of the peeled log veranda, a significant element of the west façade. Three doors, one at the dining room level and two on the lobby level, were removed and replaced by large fixed windows.

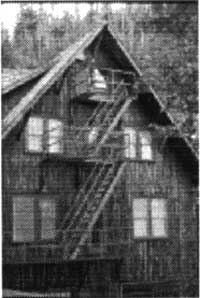

The new fire escapes. |

Four years later, in 1962, the original fire escapes at the west end of the north and south wings were replaced. The original escapes were made from peeled logs with steel treads. These were replaced by all steel fire escapes as a life safety precaution.

December 22, 1964 saw the most damaging event to the Chateau. A 200-year precipitation event caused water and debris to begin flowing down the gulch above the Chalet, and this may have been augmented by the failure of a concrete dam. Witnesses described a 17-foot wall of water and debris moving down the canyon, through the open archway in the Chalet, and down into the lower trout pond by the Chateau. Mud, silt, and debris flowed into the Chateau at the third floor level, causing approximately one-quarter of the floor to cave in. The area in the east end of the north wing is hardest hit, and the original maple dance floor is replaced by plywood subfloor over new joists, with asphalt tile finish flooring. The heavy timber support for this area was replaced by two laminated beams bolted together. These new beams sit on the original post and notch in the concrete at the east end. A report following the flood stated that about 3 feet of mud, gravel, and debris covered the rest of the dining room floor. Two feet of silt were deposited in the kitchen area, and one foot was deposited in the coffee shop. This is the reason for the wide 12" baseboard in the coffee shop as it hides the stain on the walls from the silt. The coffee shop also lost its original parquet floor in favor of asphalt tile following the flood. The second floor walk-in freezers and chef's quarters were also damaged by silt and debris, and the boiler room contained about a foot of silt. In addition, the madrone balusters on the main stair had to be replaced. An estimated 3500 cubic yards of debris entered the Chateau, and the damage to the concessionaire was estimated to total $100,000. The Chateau remained closed until May 26 of 1965, opening as scheduled for Memorial Day Weekend.

At some point the electrical system was upgraded in the Chateau, with grounded outlets installed in all rooms. Electric supplemental heaters were installed in a few of the guest rooms, especially on the lower floors. The dates of these alterations is unknown.

The interior wall finishes, comprised mostly of a pressed fiberboard material sold under the name "Nu-wood", were altered in 1989 by the application of a fire retardant glaze. The product, manufactured by American Vamag Company Inc., is sold as "Albert DS". The glaze was applied to all interior fiberboard panels, altering the original matte finish. The glaze was brushed or rolled on, and gives the walls a glossy appearance.

A final note about alterations to the structure needs to be made. The bathrooms in all areas of the building have gone through updating of one type or another fairly systematically. This is an ongoing process, as the concessionaire seeks to provide a high level of comfort in a way that is easily maintained. Few historic elements remain in the bathrooms, with the exception of lavatories, sinks, and a few fixtures in limited cases. The wall and floor finishes have been replaced in virtually all of the baths.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

orca/hsr/part1.htm

Last Updated: 07-Nov-2016