|

Petersburg National Battlefield Virginia |

|

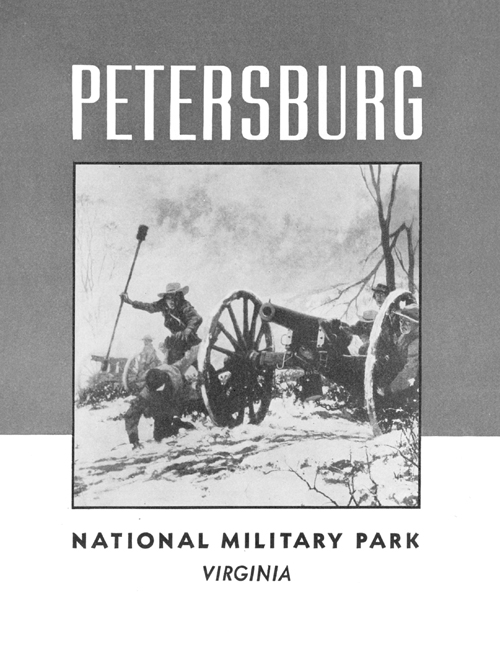

NPS photo | |

"The Key to Taking Richmond is Petersburg"

That"s what Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant believed when his forces began arriving east of Petersburg in June 1864. The campaign that brought the armies to this key rail center and main base of supply for Richmond and Gen. Robert E. Lee's Confederate Army of Northern Virginia began in May when Grant's 122,000-man Union Army of the Potomac crossed the Rapidan River and engaged Lee's army of 65,000 in a series of hard-fought battles. For a month the armies clashed, marched, and clashed again. After each encounter, Grant moved farther south and closer to Richmond. By early June the Federals were within nine miles of the Confederate capital, but Lee still blocked their path. At Cold Harbor on June 3 Grant tried by frontal assault to crush the Confederate army and enter the city. He failed in a defeat marked by heavy casualties. After Cold Harbor, Grant abandoned his plan to capture Richmond by direct attack. Instead, he secretly moved his forces to the south side of the James River and on June 15-18 threw them against Petersburg. The city might have fallen then had Federal commanders pressed their assaults and kept the few Confederate defenders from holding on until Lee's army arrived from Cold Harbor. When four days of combat failed to capture the city. Grant began what would become a nine and one-half month siege, setting up a huge supply base at City Point (now Hopewell) overlooking the James and Appomattox rivers.

A Mere Question of Time

Five railroad lines and key roadways made Petersburg important to the Confederacy. Cut them and the city could no longer supply Richmond and Lee's army. Many believed that if Richmond fell, the war would be over. But others, like Grant, knew that the war would end only when Lee's army was destroyed.

Lee knew this, too. "We must destroy this army of Grant's before he gets to the James River," he had told one of his generals. "If he gets there it will become a siege and then it will be a mere question of time." For close to 10 months Grant's army gradually but relentlessly isolated Petersburg and cut Lee's supply lines from the south. For the Confederates it marked months of desperately hanging on, hoping the people of the North would tire of the war. For soldiers of both armies it meant months of rifle bullets, artillery, and mortar shells, relieved only by rear-area tedium: drill and more drill, with both armies sometimes enjoying adequate rations, sometimes not. For the people of Petersburg it meant months of fear, hardship, and sacrifice.

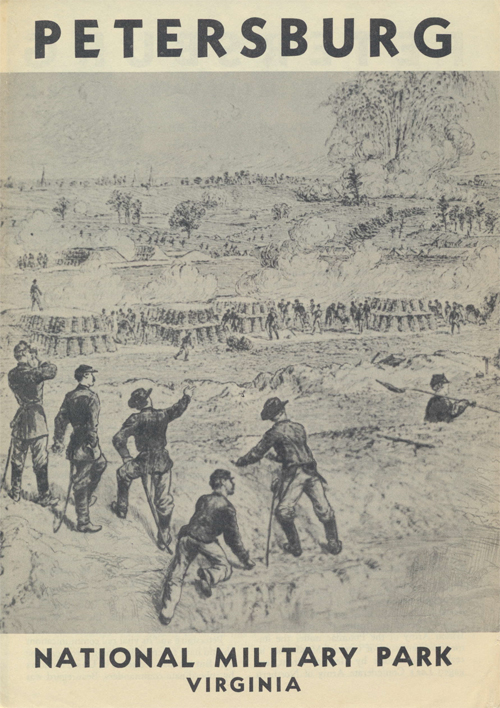

Eastern Front Grants first attempts to capture Petersburg came from the east on June 15-18. They failed miserably, costing him nearly 10,000 men, but his soldiers did sever two railroads to the city and gained control of several roads. On July 30, trying to create a breakthrough. Union troops exploded a mine under part of the Confederate line. The attempt failed and the resulting Battle of the Crater cost another 4,000 Federal casualties; the Southerners lost 1,500 men.

Western Front In August Grant struck out to the south and west against the Petersburg (& Weldon) Railroad. After three days of fierce fighting in brutal heat. Union troops were astride the iron rails near Globe Tavern. Four days later, on August 25, Lee's Confederates scored a minor victory at Reams Station, five miles south of Globe Tavern, but failed to break the Federal hold on the railroad.

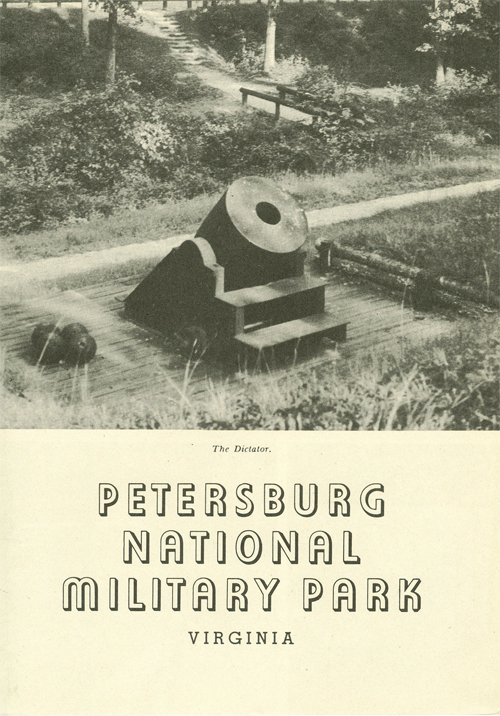

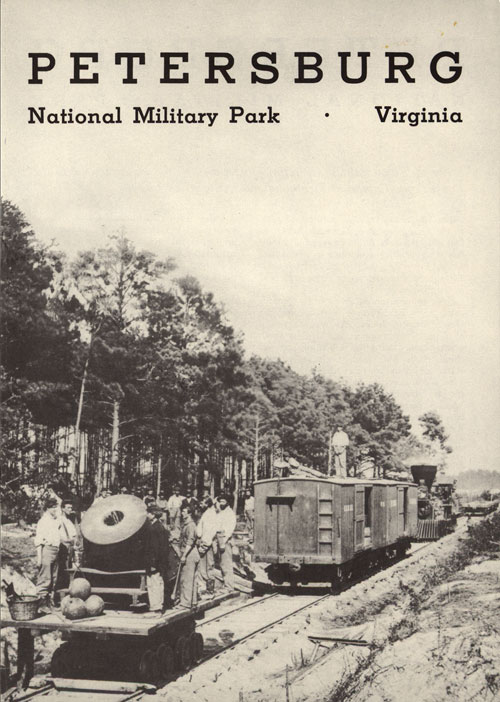

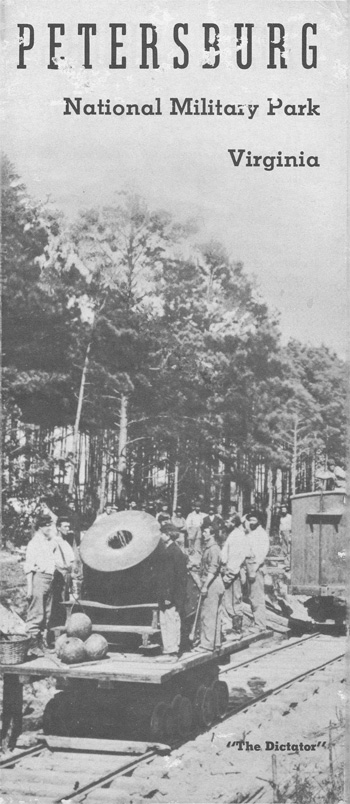

By October, Grant had moved three miles west of the Petersburg (& Weldon) Railroad and his grip on Petersburg tightened. The approach of winter brought a general slowing of military maneuvers, but everyday skirmishing, sniper fire, and mortar shelling from weapons like the "Dictator," a 17.000-pound seacoast mortar, went on. By early February 1865, Lee had only 60,000 cold and hungry soldiers in the trenches to oppose Grant's well-equipped force of 110,000. On February 5-7, Grant extended his lines westward to Hatcher Run and forced Lee to lengthen his own thinly stretched defenses. All the while supplies rattled continuously over the U.S. Military Railroad from City Point to Union troops at the front.

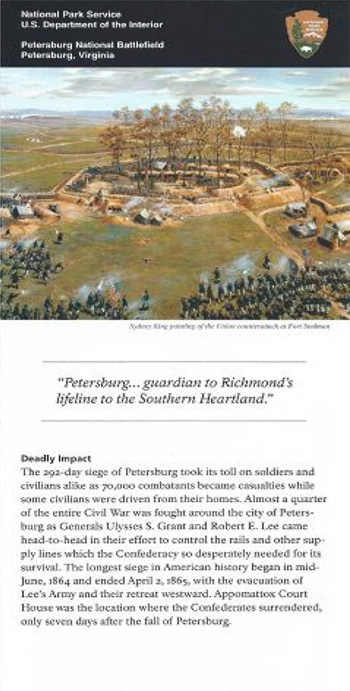

By mid-March Lee knew that Grant's superior force would either get around the Confederate right flank or pierce the line somewhere along its 37-mile length. He hoped to break the Union stranglehold on Petersburg by attacking Grant at Fort Stedman, then breach the Union line, hold the gap, and gain access to the U.S. Military Railroad and City Point just beyond. If this worked, Grant might have to give up positions to the west, and Lee could shorten his own lines. On March 25, Confederates initially overpowered Fort Stedman only to be crushed by a Union counterattack that restored the Federal line.

At Five Forks, with victory near, Grant unleashed Gen. Philip H. Sheridan with a combined force of cavalry and infantry April 1. His objective: the South Side Railroad. Sheridan smashed the Confederate forces under Gen. George E. Pickett and the next day reached the tracks beyond. On April 2, Grant ordered an all-out assault, and Lee's right flank crumbled after the initial breakthrough. That night, after telegraphing the Confederate War Department that he could "hold his position no longer," Lee began the evacuation of Petersburg and Richmond. Seven days later he surrendered his Army of Northern Virginia 110 miles to the west at Appomattox Court House.

Engines Behind the Siege

"All this had sprung out of the earth as if by magic, in less than a month."

—Brig. Gen. Regis de Trobriand, Army of the Potomac

CITY POINT

If the siege could be described as two supply systems struggling for survival, then City Point was key to the Union victory.

Between June 1864 and April 1865, City Point mushroomed from a sleepy village to a bustling supply center for over 100,000 Federal soldiers on the siege lines in front of Petersburg and Richmond. An Episcopal bishop from Atlanta, visiting Grant at City Point, was awed by the mass of military stores—"not merely profusion, but extravagance; wagons, tents, artillery, ad libitum. Soldiers provided with everything."

By July 1864, City Point provided an around-the-clock railroad operation to the front line, a half mile of wharves receiving over 100 ships a day, and the largest field hospital of the war with its own rail connection and pier. As Grant's headquarters, this point of land became the nerve center for the entire Union war effort as the telegraph system linked him to all theaters of the war.

The success of City Point enabled Grant to extend his grip on Petersburg and Richmond while cutting off Lee's supply lines at the same time. At Petersburg, Union victory arrived by sail and was delivered by rail.

"[Union shells] were thrown into and around the depot and shops so often that it was unsafe to work in them with any regularity "

—T.H. Campbell, President, South Side Railroad

PETERSBURG

Where City Point's story is one of continued expansion, Petersburg's story, as a supply center, is one of collapse under pressure and mismanagement.

By 1864, Petersburg suffered poorly maintained rail lines, labor shortages, and delays caused by Southern railroads using different rail gauges. It also faced the inefficiency of the Confederate government in securing supplies and civilian freight slowing the movement of military freight.

By mid-siege, Union shelling kept Confederate trains from reaching the South Side Depot, the central station in Petersburg. Supplies were being unloaded at points west and north of town. Still, munitions and medical supplies were ample while food ration levels fluctuated due to the fighting, the weather, and to a great degree the inefficiency of the Confederate supply system.

When the Union severed the Weldon Railroad in August 1864, it left Lee with only the Boydton Plank Road and the South Side Railroad to supply his men. The plank road fell at the end of March 1865 and Union victory at Five Forks ensured the destruction of Petersburg's last supply link and the Confederacy's collapse.

"Petersburg could not fail to be a possession coveted with equal eagerness by each combatant."

—William Swinton, correspondent, The New York Times

(click for larger maps) |

Touring Petersburg Battlefields

Petersburg National Battlefield commemorates the nine and one-half month siege upon this city from June 1864 to April 1865. There is a 33-mile auto tour of the historic sites (below), including those within the Eastern and Western Fronts, Grant's Headquarters at City Point, Five Forks Battlefield, and the Home Front in Old Town Petersburg. Plan on a full day to experience the entire battlefield tour. Service animals are welcome.

Begin your tour at the Eastern Front Visitor Center where exhibits and audio-visual programs introduce the story of the siege and its impact on the course of the Civil War. Park staff will answer questions and help you make the best use of your time. At Grant's Headquarters at City Point you will learn about the massive Union logistic and supply base, large field hospital operation, plus the story of Appomattox plantation and the Eppes family with their slaves. On the western end of the tour route is Five Forks Battlefield where Sheridan's victory over Pickett's forces ensured the collapse of Petersburg and Richmond.

Please stay on designated walking trails. Hunting for artifacts in the park with or without a metal detector is illegal. Many sites are on both public and private land. Please honor posted property lines. And remember: you will be traveling on both state and county roads, so be alert to frequent and fast-moving traffic. For firearms regulations check the park website or ask a ranger.

Eastern Front Driving Tour

Soldiers along this front suffered in trenches under constant artillery and rifle fire in lines only yards and sometimes feet apart. Nowhere else along the siege lines were the opposing armies this close.

The initial assaults that failed to capture the city and the encounters that followed shaped the siege's history on the Eastern Front. Notable were the charge of the 1st Maine Heavy Artillery upon Colquitt's Salient, the Battle of the Crater, and the Battle of Fort Stedman.

This four-mile driving tour of the Eastern Front has audio stations and wayside exhibits. Some stops have short, interpretive walking trails. Take time to explore them—your visit will be more enjoyable and informative.

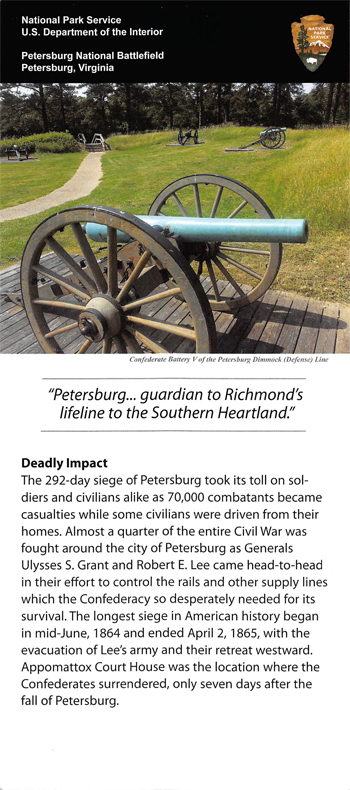

Confederate Battery 5

Located behind the visitor center, this was one of the strongest works on the

original Confederate defense line (the Dimmock Line). Federal troops captured it

on June 15, 1864. A trail leads to it and the "Dictator," a mortar used to shell

Confederate batteries north of the Appomattox River.

To follow the Eastern Front Tour route, take the second right after passing the entrance station.

Confederate Battery 8

Captured by black Union troops, this battery was renamed Fort Friend for the

Friend House located nearby. It played a major role during the Battle of Fort

Stedman in March 1865.

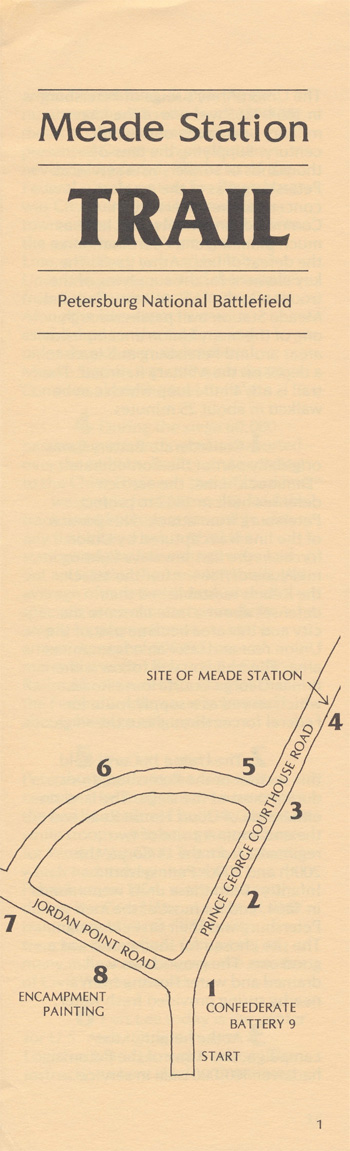

Confederate Battery 9

Black troops captured this position during the first day's fighting. This site

features examples of siege fortifications and related structures. A trail leads

to a wayside on Meade Station, an important supply and hospital depot on the US.

Military Railroad built during the siege. It is a 10-minute walk.

Harrison Creek

Driven from portions of the Dimmock Line in the opening battle on June 15, 1864,

Confederate forces dug in along the west bank of this stream for two days before

withdrawing closer to Petersburg. In March 1865 Lee's last offensive movement

(the Battle of Fort Stedman) was halted along this stream.

Fort Stedman

Lee attacked this Union stronghold on March 25, 1865, to try to relieve heavy

pressure west of the city. A loop trail leads to Colquitt's Salient, where the

attack originated. The trail passes the monument to the 1st Maine Heavy

Artillery, which, on June 18, 1864, assaulted Colquitt's Salient and sustained

the greatest regimental loss in a single action of the Civil War.

Fort Haskell

Here Union artillery, along with heavy infantry fire, stopped the Confederates'

southward advance during the Battle of Fort Stedman.

Fort Morton

From here at what was then known as the "14 gun battery," Maj. Gen. Ambrose E.

Burnside, commander of the attacking Union force, witnessed the Battle of the

Crater unfold.

The Crater

Here on July 30, 1864, at a part of Lee's line known as Elliott's Salient, Union

troops exploded a mine under the Confederate battery attempting to create a

breakthrough into Petersburg. The follow-up attack by the 9th Corps failed

miserably. Follow the trail to learn about this incredible episode.

This ends the Eastern Front Tour. To begin the Western Front Tour, continue on to Crater Road (U.S. 301) and turn left.

Western Front Driving Tour

After the Union army failed to capture Petersburg by direct assault. Grant decided to swing west and cut all roads and rail lines into the city. Through the summer and fall of 1864, Grant used his greater troop strength to attack Petersburg and Richmond at the same time, forcing Lee to defend both cities and diminishing the Confederate response.

The fight to control these dirt roads and rail lines created over 42,000 Union and 28,000 Confederate casualties (killed, wounded, captured, and disease) in the last eight months of the siege. Those lives were traded for the life these routes gave the Confederate cause and the victory their capture meant to the Union.

This 16-mile driving tour takes you to park areas south and west of town. It begins after you exit the Eastern Front at Crater Road. This is the original Jerusalem Plank Road of the war period, one of the main highways leading into the city from the southeast. Modern development has destroyed most of the earthen fortifications, but traces can still be found.

After turning left on Crater Road, go 1.7 miles to Flank Road and turn right Follow Flank Road, which parallels the Union siege line, to Halifax Road (Va. 604).

On the way you will pass the monument to Col. George W. Gowen, 48th Pennsylvania Regiment, killed in the April 2, 1865, assault on Fort Mahone. No trace of the fort remains. The Pennsylvania Monument stands where part of the fort's east wall stood. Union Forts Davis and Alexander Hays, which you will also pass, are owned by the City of Petersburg.

Fort Wadsworth

This strategic Union work occupies the site of the Battle of the Weldon

Railroad, August 18-21, 1864. The Hagood Monument here memorializes South

Carolina soldiers who attacked the Union lines in this area on August 21. From

here in September 1864 the Federals launched their fifth offensive, commonly

known as the Battle of Peebles' Farm, September 30-October 2.

Continue west on Flank Road to Vaughan Road and turn left.

Poplar Grove National Cemetery

This cemetery was established in 1866 for Union soldiers who died during the

Petersburg and Appomattox campaigns. The Western Front Visitor Contact Station

is located here.

Turn left onto Vaughan Road, then right onto Fort Emory Road. (Va. 741). Turn right onto Squirrel Level Road (Va. 613) and take first left onto Church Road (Va. 672). Turn right onto Flank Road and park on left.

Fort Fisher

This was the largest earthen fortification on the Petersburg front. On April 2,

1865, Union troops assaulted the Confederate defenses to the west from between

Forts Fisher and Welch, breaking through at what is now Pamplin Historical Park.

Access to Fort Welch is by foot trail only.

From the parking lot, turn right onto Church Road. Proceed two miles to Weakley Road and turn right. Turn left on Simpson Road and then right onto the Central State Hospital entrance road. Fort Gregg is located in the field east of the parking area. It is accessible by foot only.

Fort Gregg

On April 2,1865, during the final assault on the Confederate lines west of the

city, 600 Southern soldiers defended Forts Gregg and Whitworth (to the north)

and held off nearly 5,000 Federals for two hours, enabling Lee's army to safely

withdraw from the city that night.

This ends the Western Front Tour. To visit Five Forks Battlefield, return to Simpson Road and turn right. At U.S. 1, turn left, go south about four miles to White Oak Road (Va. 613), and turn right. Five Forks is about five miles ahead.

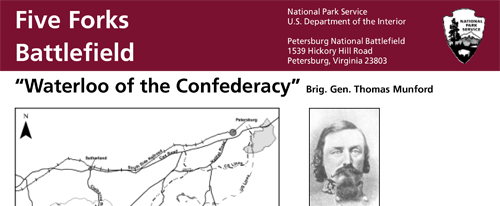

Five Forks Battlefield, April 1, 1865

Begin your auto tour at the visitor contact station. At key tour stops around the battlefield, signs tell about phases of the battle. Please use extreme caution driving to the various stops.

Union Cavalry Attacks

After fighting south of here on March 31 near Dinwiddie Court House, the

Federals moved to this area before attacking the Confederates dug in along White

Oak Road.

The Angle

This right angle entrenchment was intended to protect the Confederate left

flank. Gen. Gouverneur K. Warren's 5th Corps attacked with overwhelming numbers

and captured many prisoners.

Five Forks Intersection

This key intersection was the Federal objective. The road leading north. Ford's

Road, was the closest route to the South Side Railroad, Petersburg's last supply

line.

The Final Stand

Confederates withstood several Union cavalry attacks led by Gen. George A Custer

but withdrew from the battlefield that night.

Crawford's Sweep

Gen. Samuel Crawford's division of the 5th Corps moved against the Five Forks

intersection from the north, completing a near encirclement of the Confederate

position.

Grant's Headquarters at City Point

Appomattox Plantation

Occupied by Dr. Richard Eppes and his family until 1862, when the arrival of

Union gunboats on the James River convinced them to move to Petersburg. Their

home, known as "Appomattox," served as offices for the U.S. Quartermaster and

his staff during the siege.

Grant's Cabin

When he arrived at City Point on June 15, 1864, Grant's headquarters was in a

tent on the east lawn of Appomattox. The cabin was built in November 1864 and is

the only remaining structure from a series of 22 log cabins erected for Grant

and his staff. Grant's wife and son Jesse stayed with him in the cabin during

the last three months of the siege.

Old Town Petersburg: The Home Front

Old Town is the historic commercial core of Petersburg. It retains much of its historic character and vestiges of the 292-day siege. Be sure to check out some of the museums and historic buildings to learn about the people and history of Petersburg before, during, and after the Civil War. For those wishing to explore the city more thoroughly, a 68 stop Auto Tour of Civil War Petersburg is sold at the park visitor centers and other places.

Source: NPS Brochure (2012)

|

Establishment

Petersburg National Battlefield — August 24, 1962 |

For More Information Please Visit The  OFFICIAL NPS WEBSITE |

Brochures ◆ Site Bulletins ◆ Trading Cards

Documents

A History of Petersburg National Military Park, Virginia (Lee A. Wallace, Jr., 1957)

A History of Petersburg National Battlefield to 1956 and A History of Petersburg National Battlefield 1957-1982 (Lee A. Wallace, Jr. and Martin R. Conway, 1983)

A Report on the Physical History of the Crater, Petersburg, Virginia (Joseph P. Cullen, August 1975)

Alternative Transportation Feasibility Study, Petersburg National Battlefield (November 13, 2012)

Appomattox Manor-City Point: A History (Harry A. Butowsky, 1978)

Battle of Burgess' Mill (Raleigh C. Taylor, October 8, 1938)

Battle of the Weldon Railroad (Edward C. Bearss, undated)

Campaign for Petersburg NPS History Series (Richard Wayne Lykes, 1970)

Center Hill Mansion (J. Walter Coleman, December 17, 1936)

Coastal Hazards & Sea-Level Rise Asset Vulnerability Assessment for Petersburg National Battlefield: Summary of Results NPS 325/187657 (K.M. Peek, H.L. Thompson, B.R. Tormey and R.S. Young, February 2023)

Cultural Landscape Report of Crater Battlefield, Petersburg National Battlefield, Petersburg, Viginia (Timothy W. Layton, 2017)

Cultural Landscape Report for the Federal Left Flank and Fish Hook Siegeworks, Petersburg National Battlefield (Roger Charles Sherry, October 2004)

Cultural Landscape Report: Poplar Grove National Cemetery, Petersburg National Battlefield, (Jon Auwaerter, 2009)

Cultural Landscapes Inventory: Eastern Front, Petersburg National Battlefield (2021)

Cultural Landscapes Inventory: Five Forks Battlefield, Petersburg National Battlefield (2020)

Cultural Landscapes Inventory: Fort Stedman, Petersburg National Battlefield (2021)

Cultural Landscapes Inventory: Initial Assaults, Petersburg National Battlefield (2021)

Cultural Overview of City Point, Petersburg National Battlefield, Hopewell, Virginia (Audrey J. Horning, December 2004)

Draft General Management Plan / Environmental Impact Statement, Petersburg National Battlefield (March 2004)

Earthwork Management at Petersburg National Battlefield (Dave Shockley, June 2000)

Ecology Web Ranger Program, Petersburg National Battlefield (Date Unknown; for reference purposes only)

Foundation Document, Petersburg National Battlefield, Virginia (October 2016)

Foundation Document Overview, Petersburg National Battlefield, Virginia (January 2016)

Geologic Map of Petersburg National Battlefield (May 2024)

Geologic Map of Petersburg National Battlefield: City Point (May 2024)

Geologic Resources Inventory Report, Petersburg National Battlefield NPS Science Report NPS/SR-2024/190 (Trista L. Thornberry-Ehrlich, September 2024)

Historic Furnishings Report: Grant's Cabin, City Point Unit, Petersburg National Battlefield, Virginia (Donald C. Pfanz, 1989)

Historic Structure Report, Physical History and Analysis Section: Appomattox Manor, City Point Unit, Petersburg National Battlefield, Virginia (Richard G. Turk and G. Frank Willis, October 1982)

Historic Structure Report for Appomattox Plantation Outbuildings, Pecan Avenue, Hopewell, VA 100% Draft (The Collaborative, Inc. and Atkinson Noland & Associates, Inc., June 12, 2017)

Historic Structures Report for Fort Haskell, Historic Structure Report, Petersburg, Virginia (William G. Gray, April 1964)

Historical Base Maps: Appomattox Manor-City Point (G. Frank Williss, January 1982)

Interpretive Prospectus for Petersburg National Battlefield (John T. Willett and James F. Kretschmann, August 1964)

Meade's June 18 Assault on Petersburg Fails and the Investment Begins (Edwin C. Bearss, 1964)

National Register of Historic Places Nomination Forms

Appomattox Manor (Virginia Historic Landmarks Commission Staff, May 2, 1969)

Five Forks Battlefield (Stephen Lissandrello, February 20, 1975)

Natural Resource Condition Assessment: Petersburg National Battlefield, Virginia NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/PETE/NRR-2013/704 (T.R. Lookingbill, B.M. Miller, J.M. Madron, J.C. Finn and A.T. Valenski, August 2013)

Painting Number One, Petersburg National Battlefield: Encampment Site-Meade Station Trail (Edwin C. Bearss, 1964)

Petersburg Battlefields: Historical Handbook Series No. 13 (Richard Wayne Lykes, 1951, revised 1956)

Petersburg Battlefields: Historical Handbook Series No. 13 (Richard Wayne Lykes, 1951, reprint 1961)

Pontoon Bridges of the Campaign in Eastern Virginia, 1864-65 (Raleigh Taylor, April 1940)

Poplar Grove Cemetery History (Herbert Olsen, May 31, 1954)

Reems' Station and the Federal Left Flank, July-August 1864 (R.C. Taylor, 1945)

Report on Appomattox Manor, Hopewell, Virginia (December 1962)

Report on the Reproduction of 'The Dictator' or 'Petersburg Express' - A 13-Inch Sea Coast Mortar Used in the Siege of Petersburg (Nanning C. Voorhis, Summer 1936)

Slavery and the Underground Railroad at the Eppes Plantations. Petersburg National Battlefield: Special History Study (Marie Tyler-McGraw, 2005)

The Attack on Petersburg, June 9, 1864 (Edwin C. Bearss, February 1966)

The Battle of the Boydton Plank Road, October 27-28, 1864 (Edwin C. Bearss, 1966)

The Battle of the Jerusalem Plank Road, June 21-24, 1864 (Edwin C. Bearss, February 1966)

The Battle of Peebles' Farm (Raleigh C. Taylor, September 1939)

The Battle of Reams' Station (Edwin C. Bearss, 1964)

The Battle of the Crater, Hammering Fails for the Last Time (Raleigh C. Taylor, October 1938)

The Battle of Hacher's Run, February 5-7, 1865 (Edwin C. Bearss, February 1966)

The June 15, 1864, Attack on Petersburg (Edwin C. Bearss, 1964)

Visitor Study: Summer 2011, Petersburg National Battlefield NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/NRSS/EQD/NRR-2012/508 (Mystera Samuelson, Marc F. Manni, Yen Le and Steven J. Hollenhorst, April 2012)

Books

pete/index.htm

Last Updated: 26-Sep-2024