|

SAN ANTONIO MISSIONS

Indian Groups Associated with Spanish Missions of the San Antonio Missions National Historical Park |

|

THE STUDY OF MISSION INDIANS: LIMITATIONS

Studies involving Indian groups of the San Antonio missions have not been noted for calling attention to the deficiencies of the Spanish documents, or for explaining why it is so difficult to make sense out of such information as happened to get recorded in those documents. These studies sometimes give the impression that scholars have already solved most of the problems connected with ethnic group identities, pre-mission territorial ranges, specific groups represented at each mission, the Indian languages spoken, and cultural affiliations of the various Indian groups. Few of these problems have yet been satisfactorily solved. If non-specialists need information about mission Indians for purposes of public education, they can be misled by specialists who have not placed all their cards on the table. A scholar's opinions are much more valuable when they are preceded by frank statements about the evidence used in support of those opinions. In the following sections some of the major limitations of mission Indian research are discussed.

The San Antonio Missions

The Spanish missions of San Antonio were established relatively late in time and reflect the late Spanish occupation of Texas as compared with that of northeastern Mexico. As noted above, the first Spanish settlements of northeastern Mexico began about 1590, and it was not until 1718, or 128 years later, that San Antonio began to be settled by Spaniards.

Colonial Spanish San Antonio was unique in that it was a mission center with a larger number of missions than other centers of the region. Five rather closely spaced missions were built in what is now the southern part of the City of San Antonio. A sixth mission was authorized but never constructed. The location of San Antonio is the key to understanding this proliferation of missions. San Antonio was for some time on the northern edge of the Spanish settlement frontier, and it was also on the main travel route from Mexico to eastern Texas, where the Spaniards were attempting to halt French expansion from Louisiana. Furthermore, San Antonio was for several decades near a concentration of displaced Indian groups who were demoralized by Spanish and Apache encroachments and increasingly became willing to enter missions. The Spanish missionaries, many of whom had worked in unsuccessful missions elsewhere, recognized the potential of San Antonio for Indian conversion and took advantage of it.

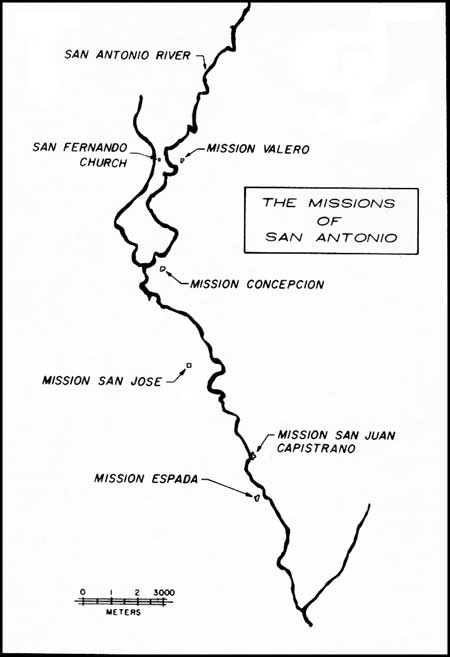

The five missions of San Antonio were established at various times between 1718 and 1731. Their full names are San Antonio de Valero (1718), San José y San Miguel de Aguayo (1720), Nuestra Señora de la Purísima Concepción de Acuña (1731), San Juan Capistrano (1731), and San Francisco de la Espada (1731). For convenience these missions will hereafter be referred to by the following shortened names: Valero, San José, Concepción, Capistrano, and Espada (Fig. 3). All except San José had previously been in existence elsewhere, but they had failed in their first locations and were moved to San Antonio. Valero, first known as San Francisco Solano, was originally established in northeastern Coahuila, where it had been located at three different places. Concepción, Capistrano, and Espada were established in eastern Texas for various groups of Caddo Indians and were all moved to San Antonio in the same year.

|

| Figure 3. The Missions of San Antonio. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

In this study attention is focused on Indian groups represented at the four missions of the San Antonio Missions National Historical Park. Valero is not included in the park, and its Indian groups will not be given detailed consideration. It will be necessary, however, to mention some of the Indian groups of Valero because all of the San Antonio missions competed with each other for Indian neophytes, and it is of special interest to know the area or areas from which each mission drew its Indian populations.

Total Indian Population at Each Mission

The limited information available indicates that the total Indian population at each San Antonio mission was at no time very large, never exceeding 400 and rarely exceeding 300. These figures are derived from a table compiled by Schuetz (1980b:128) that summarizes the best information now known. It is of interest to note that these figures correspond roughly to the maximum figures given for the largest native Indian encampments recorded in pre-mission times.

The recorded mission figures fluctuated from time to time. The mission population increased notably when there was considerable displacement of Indian groups from some part of the surrounding area. It declined during epidemics or when Indians deserted the missions. Desertion was more common in the earlier days of each mission, apparently because some groups found it hard to adjust to mission discipline. They seem, in most cases, to have gone back to their former territories. Most of them were eventually persuaded by missionaries to return to their missions. Some groups appear to have become dissatisfied with living conditions in their mission and moved to another mission. A few groups were characterized as fickle by missionaries because they sampled life at several missions before settling down to one. There was also a certain amount of seasonal desertion. During summer some Indians left to collect traditional wild plant foods, such as prickly pear fruit, and perhaps some of these were also motivated by a desire to escape summer field work on mission farmlands. With the passage of time, however, this pattern of desertion and return declined in importance, particularly after Apache raids in the area became more common. The table compiled by Schuetz reveals notable population decline in all missions after the year 1775. By that time not many remnants of Indian groups native to the region still survived, and thus fewer were entering missions.

Indian Group Names

In the study of Indians who formerly lived in southern Texas and northeastern Mexico, the first objective must be to establish identities for each of the basic hunting and gathering units. In European documents the most useful indicator of a specific ethnic group is its recorded name. Indian group names are exceedingly numerous in these documents. Unfortunately, one cannot equate every name with a separate ethnic unit. It does not take much research to discover that some names are not quite what they seem to be. Two similar names may refer to the same group or to two separate groups. Two dissimilar names may refer to the same group. One group may be known by a name of Spanish origin and also by one or more native names. Several groups may be known by different names, but all of them may also be known by the same collective name. A further complication results from the fact that it is sometimes difficult to distinguish a native personal name from a native group name. In many cases the documentation is so poor that overlapping names cannot be demonstrated.

It is not commonly realized how much confusion has resulted from the fact that European documents sometimes spell the name of a specific Indian group in many different ways, sometimes 50 or more, depending upon the phonetic complexity of the name. Some names are so badly distorted that scholars at times have regarded two or more variants of the same name as names of separate Indian groups. This has led to recognition of more Indian groups in the region than actually existed (Campbell 1977). Detailed comparative studies of name variants, thus far few in number, are badly needed, as is well illustrated by the difficulties encountered by Schuetz (1980b) in linking name variants with valid Indian groups recorded in the registers of Mission Valero.

Primarily because the basic research is incomplete, modern scholars have not yet agreed on a set of standardized names for use in referring to Indian groups of this region. The first concerted effort to do this was during preparation of the Handbook of American Indians North of Mexico (Hodge 1907-1910). Numerous errors were made that are only now beginning to be corrected. In this report we follow, whenever feasible, the spelling of group names given in the Handbook of American Indians North of Mexico (ibid.).

Number of Indian Groups at Each Mission

It cannot be assumed that remnants of all Indian groups of the region entered a Spanish mission somewhere. Many group names have been recorded for which there is no evidence that links them with any Spanish mission, either at San Antonio or elsewhere. What happened to each of these non-missionized groups remains uncertain. Some groups probably lost their identities very early, before many missions had been established.

Although it is difficult to cite good cases, there is enough evidence to show that, prior to mission entry, a small remnant of one displaced group sometimes merged with another ethnic remnant much larger in size and thereby lost its identifying name. This suggests that a fairly large group recorded as bearing a certain name may actually have been an amalgamation of two or more displaced groups who were earlier known by different names. These hidden effects of extensive displacement undoubtedly account for the disappearance of some ethnic group names from later documents. These considerations further suggest that population figures recorded in the early 18th century for some of the larger Indian groups, either prior to or after mission entry, may be misleading. Such groups may have been larger simply because they were accretions. In later times it is also possible that some group remnants chose to join their overwhelming enemies, the Apaches, rather than to enter Spanish missions.

It also cannot be assumed that all remnants of a particular Indian group went to one particular mission. Comparative studies have already shown, for example, that some groups entered only one of the San Antonio missions, and other groups entered two or more of the San Antonio missions. Some of the latter also entered missions elsewhere, as along the Rio Grande in northern Tamaulipas and northeastern Coahuila, or at Goliad and Refugio near the Texas coast Remnants of the same group did not, however, enter various missions simultaneously. They entered at various times, and this seems to indicate that progressive fragmentation and population decline governed these decisions.

It is important to realize that the total number of Indian groups represented at each of the San Antonio missions will never be known precisely because of inadequate records. The best sources of information are the baptismal, marriage, and burial registers that were kept at all Spanish missions. These indicate the ethnic affiliation of many Indian individuals, particularly those who accepted Christianity. Unfortunately, all of these registers have not survived, or at least have yet to be found. Of the San Antonio missions, the registers of Valero have survived in fairly good condition; the early marriage register of Concepción has survived; for the remaining San Antonio missions there are only register fragments from the latter part of the mission period, when ethnic affiliation was less commonly recorded.

It is not a simple matter to analyze the mission registers and determine the names of all bona fide Indian groups that were represented at a mission. Some register pages are missing or are damaged in various ways and cannot be fully read. The handwriting is not always easy to read, and each group name is spelled in various ways by the missionaries who made the register entries. The same Indian individual may be identified in various entries by two, three, or even four ethnic group names. Sometimes the correct identification can be determined by analysis of the appropriate register entries, sometimes not.

Those who have searched mission registers for Indian group names have usually paid little attention to each others' efforts. Lists of Indian groups have been compiled for each mission, and comparisons of these lists reveal many discrepancies. For example, Bolton (in Hodge 1910 Vol. II:426) published a list of group names which he had obtained from the Valero registers. Santos (1966-1967) also compiled a list of Valero groups, but he used only the burial register. Thus, Santos missed group names that appear only in the baptismal and marriage registers. As Santos did not compare his list with that of Bolton, a reader who does not know of Bolton's list may think that Santos has identified all groups recorded at Valero. Schuetz (1980b: 52-54) has recently compiled a list based on analysis of all three Valero registers, but she does not compare her list with the lists of Bolton and Santos. Confusion results because discrepancies in the three lists are not noted and explained. Bolton's list has names which Schuetz apparently did not find in the registers, and Schuetz's list has names which Bolton appears not to have seen. It is evident that there are pitfalls in the matter of identifying Indian groups recorded in mission registers, and that each compiler is obligated to explain discrepancies. Otherwise a complex matter is made to appear deceptively simple.

When mission registers are lacking, other kinds of documents must be used to discover the names of Indian groups represented at each mission, and such records usually mention only the names of groups that were represented by fairly large numbers of individuals. As additional documents come to light, it may be expected that the list of Indians represented at each mission will slowly increase in length.

As the record now stands, it would appear that far more Indian groups were represented at Valero than at each of the four missions of the historical park, but analysis of the documentary record shows that this disparity is more apparent than real. We have much better records for Valero than for the other San Antonio missions.

It is instructive to compare the records of Valero with those of San José, two missions that were established at San Antonio about the same time (1718 and 1720, respectively). For San José we have no register information prior to the year 1771. The list of Indian groups recorded for Valero is about four times as long as the list compiled for San José. Missions Concepción and Espada were established at San Antonio in the same year (1731), but the list of Indian groups recorded for Concepción has, until recently, been about twice as long as the list for Espada. The difference is best explained by the fact that the early marriage register of Concepción has survived. It may therefore be concluded that the number of identified Indian groups for a given mission is smaller when some or all of its registers have been lost.

Size of Mission Indian Groups

Most Indians probably entered missions because displacement, fragmentation, and population decline had made them deeply discouraged about the prospects of survival elsewhere. Most of the San Antonio missions contained remnants of many specific Indian groups, and these remnants varied considerably in size. Approximate figures for group size can be determined by analysis of mission registers when these are available. It must, however, be realized that the registers sometimes failed to record the ethnic affiliation of an individual, and also that many Indian individuals at missions were never recorded because they refused to be baptized into the Christian faith. Despite inadequate records, it is reasonably clear that at each mission a few Indian groups were represented by far more individuals than others. Most groups were represented by relatively small numbers of individuals. When mission registers are available, as at Mission Valero, it is evident that some Indian groups were represented by one individual only, or by no more than two, three, or four individuals (see tables compiled by Schuetz 1980b:49-55). Historians have sometimes made statements which imply that each group whose name can be associated with a given mission was represented by a substantial number of individuals. It is best to be cautious and base statements on such concrete figures as are available. It seems obvious that if a mission had no more than 300 individuals at any one time, and if 20, 30, or more Indian groups were represented, most groups could not have been represented by very many individuals.

In general, it may be said that the remnants of specific Indian groups who entered missions during the earlier part of the mission period were larger in size than they were later. As time passed, the population fragments became smaller in size, and there were fewer individuals to enter missions.

Pre-Mission Locations of Indian Groups

It must be stressed that the Spanish documents do not satisfactorily Indicate where all Indian groups represented at the San Antonio missions lived before entering the respective missions. For some groups nothing is recorded except the identifying name; for other groups the documents sometimes yield clues which suggest association with some general area. The recorded statements about location are usually few in number and refer to one particular time or to a relatively short period, making it difficult to assess how much displacement was involved. It is, thus, not often that the aboriginal territory occupied by a group can be positively identified. In the ethnohistoric literature of this region, the tendency has been to assume that most of the recorded group locations indicate aboriginal locations. This has obscured the dynamic aspects of Indian group displacement.

Those who have written about the Indians of southern Texas and northeastern Mexico have sometimes presented maps purporting to show group locations. Such maps show the locations of some groups but not of others; this fact is not clearly indicated by map titles or by accompanying explanations. When these maps are checked against written documents, it is found that some groups are placed in areas where they were never reported to be living, and the relative positions of groups shown in a restricted area usually cannot be confirmed. The documents are not sufficiently informative about group locations to permit compilation of reliable maps for any particular date or period.

Indian Languages

Cultural classification of the numerous Indian groups of southern Texas and northeastern Mexico has been based mainly on linguistic classification. This procedure works best when languages are still spoken and can be studied in detail, but for this particular region all of the Indian languages formerly spoken are now extinct. Hence all that can be said about linguistic relationships must be based upon speech samples (vocabularies and texts) that were written down by Europeans before the languages became extinct. In this region few languages were documented, and some of the samples are small, sometimes consisting of vocabularies that total less than 25 words. Except for a few missionaries, Spaniards of the Colonial period lacked the skills and motivation needed for collecting language samples.

It is not now possible to compile a list of Indian groups who spoke the language or dialect represented by each recorded sample. Occasionally Spanish documents refer to two or more Indian groups who spoke the same language, or to two groups who spoke different languages, but they seldom say enough to permit identification of the languages involved. For the majority of Indian groups whose names appear in documents, nothing is recorded about language.

Classification of Indian languages in this region is a modern phenomenon and did not begin until the middle 19th century, when the language known as Coahuilteco was first recognized by linguists. Coahuilteco is by far the best documented language of the region, primarily because two missionaries prepared manuals in this language for use in the administration of church rituals (Garcia 1760; Vergara 1965). Neither these manuals nor other documents specify the names of all Indian groups who originally spoke Coahuilteco. Remnants of other linguistic groups also entered the same missions, and some of these had learned to speak Coahuilteco as a second language because it had become the dominant Indian language spoken in the missions.

After a few additional language samples had become known for the region, linguists concluded that these represented languages related to Coahuilteco (Powell 1891; Sapir 1920; Swanton 1940). This conclusion led ethnohistorians and anthropologists to believe that the region was occupied by numerous small groups who spoke related languages and, thus, probably also shared the same basic culture.

Detailed comparative studies of language samples from this region began with Swanton (1915), who later published vocabularies for the languages designated as Coahuilteco, Solano, Comecrudo, Cotoname, Maratino, Araname, and Karankawa (Swanton 1940). The vocabularies were compared for evidences of linguistic relationship. Although he found the evidence far from satisfactory, Swanton expressed the opinion that the three best documented languages, Coahuilteco, Comecrudo, and Cotoname, were probably related. He further suggested that these languages might be more distantly related to the Karankawa and Tonkawa languages. Other linguists, apparently not bothered by the problem of inadequate samplings accepted Swanton's opinions, which were in vogue for several decades.

The first indication that all languages of the region were not related to Coahuilteco came when Eugenio del Hoyo (1960), a Mexican historian, collected a lengthy list of words and phrases, which were accompanied by their meanings in Spanish, from documents in the archives of Nuevo León. These were later analyzed by Gursky (1964), a linguists who considered them to represent a new language, Quinigua, which he was unable to relate in any way to Coahuilteco.

More recently Ives Goddard (1979), a linguist who has specialized in North American Indian languages, has re-examined the linguistic materials presently available for southern Texas and the adjoining part of northeastern Mexico. The languages inspected include Tonkawa, Coahuilteco, Karankawa, Comecrudo, Cotoname, Solano, and Aranama. After applying the more rigorous analytical techniques of modern linguistics, Goddard failed to find enough evidence to demonstrate that any of these languages are related. This does not mean that they are definitely not related, merely that no one can convincingly prove them to be related. Goddard also pointed to statements made by early Spanish observers which indicate that still other languages were spoken in the same area, languages that were never documented by vocabularies or texts. He further suggested that the area was probably characterized by linguistic diversity, not by the widespread linguistic uniformity envisioned by earlier linguists. This reversal in linguistic interpretation calls for a re-examination of previous conclusions about a widespread uniformity of culture.

Indian Cultures

As noted in the Preceding section, cultural classification for this region has been based on linguistic considerations. It has not grown out of detailed studies of similarities and differences in cultural characteristics recorded for specific Indian groups associated with particular areas.

Only those who have extensively searched the archival collections for recorded information on culture seem to realize how little was recorded for the Indian groups of the region. For Indians associated with the four missions of the historical park, the recorded information on culture is notably minimal. Very few of the early European observers were sufficiently interested in specific Indian groups to describe their behavior in detail. Most observers apparently believed that the various hunting and gathering groups were all very much alike and that there was no point in showing how one group differed from another, or how groups in one area differed from groups in a nearby area. Most of what these observers recorded was incidental to other interests and appears to be random, that is, without definite aim, purpose, or reason. A substantial amount of cultural description was generalized for Indian groups of a restricted area without any specific group names being mentioned. Hence the same kinds of cultural information were not recorded for many specifically named groups, and this has made it even more difficult to ascertain valid similarities and differences. Furthermore, in the early documents there are inconsistencies and contradictions which scholars have not always recognized. These various documentary deficiencies have too often been ignored by most writers, who seem to follow the early observers in believing that Indian groups of the region shared the same culture.

The concept of a widespread "Coahuiltecan culture" was developed in the early 1950s by F. H. Ruecking, Jr. (1953, 1954, 1955). It was predicated on the belief that the Coahuilteco language was spoken over a very large area in southern Texas and northeastern Mexico, and that all other languages documented for the same region were closely related to Coahuilteco. As noted in the preceding section, recent linguistic studies have rendered this belief questionable. The Coahuiltecan culture as described by Ruecking is a composite of miscellaneous descriptive details that were recorded over a period of several hundred years. The recorded bits of information pertain to miscellaneous Indian groups, some not even identified by name, who lived in limited portions of the region. Ruecking included everything he could find in the published literature (he did no archival research), but he failed to recognize that some of the generalized cultural information came from southern Tamaulipas and is in part referable to certain Indian groups who practiced agriculture. He made no allowances for cultural change through time and ignored the recorded differences between Indians of certain areas.

It is now apparent that no single Indian group of the region could have had a culture that included all of the features of Coahuiltecan culture described by Ruecking. His lack of discrimination in the use of recorded cultural information has led to gross oversimplification and considerable error. Ruecking's dragnet collecting of cultural information resulted in a useful compilation for the area as a whole, but it is no longer possible to use his concept as the basis for identifying most of the Indian groups as Coahuiltecan in culture. If language is to be used as the basis for cultural classification, one must, in each case, produce evidence that the Coahuilteco language was spoken before inferring a Coahuiltecan culture. According to the evidence now available, less than 60 Indian groups can be identified as probable speakers of the Coahuilteco language (Campbell 1983), and most of these can be assigned to an area restricted to southern Texas and parts of northeastern Coahuila. Much of what Ruecking included in his description of Coahuiltecan culture was not recorded for any of these Coahuilteco speakers.

For Indian groups associated with the historical park missions, some categories of culture are either missing from, or sparingly recorded in, documents. Little detail is given about how artifacts were made and used; about the methods of hunting, fishing, and plant food collection; or about how various kinds of foodstuffs were processed and cooked. There is also very little detail recorded about Indian religious concepts and rituals, perhaps because Spaniards of the time were so strongly committed to evangelical Catholicism. This dearth of information makes it virtually impossible to comment on specific changes in the cultures of Indians while they were in the San Antonio missions. It is gratuitous to speculate about new ways of doing things that were introduced when one or more Indian groups entered a mission for the first time, or to speculate about the times when various elements of the Indian cultures disappeared at missions. One must be careful not to read things into the record.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

campbell/sec1.htm

Last Updated: 26-Apr-2007