|

Saint Croix National Scenic Riverway

Time and the River: A History of the Saint Croix A Historic Resource Study of the Saint Croix National Scenic Riverway |

|

CHAPTER 4:

Up North: The Development of Recreation in the St. Croix Valley

Written with Rachel Franklin Weekley

In 1936, the twenty counties of northwest Wisconsin cooperated in a tourist brochure that promoted the region as "Indian Head Country." The name was derived from the shape of Wisconsin's St. Croix borderland that appeared to the imaginative as the silhouette of a human profile. Pierce County was the chin, St. Croix County the mouth, and Burnett County formed a prominent "Roman" nose. For the tourist boosters the choice of "Indian Head" was obvious. Not only did the large nose suggest the Indian profile on the "Buffalo" nickel then in circulation, the Indian was the symbol of all that was uniquely American. The Indian was a symbol of wild, unrestrained nature. Never for a moment did the tourist promoters think of labeling the twenty county area "Swedish Head," or "Polish Head" country. Such a label was, of course, ludicrous even if it did call to mind some of the people who had devoted their lives to the unsuccessful effort to bring agriculture to the cutover. That history was to too recent, too painful, too prosaic. It would be as untrampled nature — a romantic, even ridiculous impossibility given the history of logging and farming — that the St. Croix region would be sold to the public.

As the St. Croix River began its emergence from wilderness to a developed and settled region, American attitudes towards nature and the wilderness were in a process of transformation. During the colonial era, America was seen, on the one hand, as a land of abundance and a refuge from Old World ills, but its primeval forests were also seen as a hostile wilderness filled with savage beasts and men. While it bestowed bounty on those able to meet its challenges, nature was a harsh taskmaster and it extracted a heavy price from those less fit. What enabled Americans in the first half of the nineteenth century to change their perspective on nature was the industrial revolution. Man became the master of nature instead of its victim. The industrial revolution, however, also scarred and even destroyed nature's beauty and exposed its fragility. At the hands of man nature was no longer to be feared, but cherished. [1]

This appreciation of nature had its roots in the eighteenth century Enlightenment when the natural world was held up as inspiration and a model for social organization. If human society followed the laws of nature instead of the dictates of the artificial, superstitious inequalities stemming from the medieval world of feudalism and traditional religion, it could find peace and harmony. These beliefs found expression through political, economic, social, and artistic channels. But whatever the ultimate aim, nature had to be experienced first hand. In eighteenth century England the term "picturesque" came to describe a natural scene that depicted the beautiful and evoked the sublime. This perspective on nature inspired the popular artistic genre of landscape painting. This glorification of nature continued into the early nineteenth century Romantic Movement with its reaction against the ugliness of the industrial revolution. Nature was not only beautiful, sublime and a guide to social order, but also a source of spiritual renewal for people severed from their rural roots in ugly urban cities.

In the United States the Romantic Movement developed its own unique perspective on nature. The English writer William Gilpin introduced to Americans the practice of rambling about the countryside in search of the beautiful and sublime and made "picturesque travel" a popular recreational pastime. It was trumpeted as a way to exercise both the mind and the body. Gilpin's tours of England's North and Lake Countries were used as models for American expeditions. The sparsely settled American landscape was ripe for "picturesque travel." The unspoiled vistas, mountains, valleys, lakes, and rivers came to be considered America's cathedrals and works of art that rivaled the manmade art treasures of the Old World, and certainly equaled or excelled any scenic wonders in Europe. Americans expanded the definition of the picturesque and applied it to their more rugged and unspoiled wilderness. The American wilderness came to be seen as part of the country's unique heritage and a national treasure, and became the subject matter for the paintings of the Hudson River School, the poetry of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, the prose of Ralph Waldo Emerson, and the philosophy of Henry David Thoreau. [2]

While the industrial revolution marred nature, it also ironically made nature more possible to enjoy. The invention of the steamboat and the railroad allowed people to experience natural wonders first-hand without forgoing many of the creature comforts of civilization. There they could experience spiritual renewal and regeneration from the more fast-paced and wearisome world of the city. While the wealthy had always been able to escape the city, their motivations had been chiefly to escape the heat, the smell, and the diseases that often plagued urban centers. Their country, mountain, or seashore retreats sought to duplicate the comforts of home, rather than lure them into the world of nature. But increasingly throughout the nineteenth century the wealthy were joined in these rural retreats by the expanding middle class who turned to the world of nature for health, recreation, and social activity.

This cultural context shaped the way late eighteenth and early nineteenth century white explorers and settlers perceived the St. Croix River Valley when they first ventured there. Its distinctive geographic formations, such as the "Old Man of the Dalles," provided explorers with navigation references, but also drew them into the unique splendors of the river valley. George Nelson, the Canadian fur trader who wintered in the valley in 1802-3, noted in his diary:

Whenever this country becomes settled how delightfully will the inhabitants pass their time. There is no place perhaps on this globe where nature has displayed & diversified lands & water as here. I have always felt as if invited to settle down & admire the beautiful views with a sort of joyful thankfulness for having been led to them. There is nothing romantic about them, frightful rock, & wild & dashing water falls. Nature is here calm, placid & serene, as if telling man, in language mute, indeed, -- not addressed to the Ears, but to heart & Soul: It is here man is to be happy: a genial & healthy climate — the rigour [sic] of winter scarcely three months, & in that time no very severe cold: I have diversified the land with hundreds of beautiful lakes all communicating with each other by equally beautiful streams, full of excellent fish, & ducks of twenty Species, Swans, & geese with abundance of rice for you & them. The borders well furnished with grapes, plums, thorn apples & butternut &c, &c. The Woods Swarming with Dears [sic] & bears & beavers: not one noxious or venomous animal insect or reptile: come my children, come & settle in this beautiful country I have prepared for you, & be happy. [3]

Nelson's paean to the Upper St. Croix Country was most likely added to his diary many years after his winter in the valley. It reflects the power of a picturesque landscape to overcome the realities of Nelson's last days on the river: cold, wet spring weather, rapids, portages, mosquitoes swarming, and king fear of a Dakota attack. Romanticism was necessary to transform a a truly wild landscape into a picturesque retreat and the mastery that came with technology and private property made possible the evolution of the Upper St. Croix from a battleground between the Chippewa and Dakota to the white man's "Indian Head" Country vacation destination.

Figure 29. The "sublime" and romantic Dalles of the St.

Croix was captured in this 1848 oil painting by Henry Lewis. Titled the

"Gorge of the St. Croix" the painting helped to promote the St. Croix as

an ante-bellum tourist destination.

Tourism in the Ante-bellum Years

Although it was the glowing accounts of the St. Croix's abundant natural resources that enticed the first permanent settlers to the region, tourists also began venturing into the St. Croix Valley to enjoy its natural splendors in the first half of the nineteenth century. "It was the Mississippi and its steamboats that inaugurated the trade and spread the fame of Minnesota as a vacation land," wrote historian Theodore C. Blegen, "promising to the enterprising tourist the adventure of a journey to a remote frontier coupled with the enjoyment of picturesque scenery and of good fishing and hunting." The first steamboat tourist to Minnesota was an Italian named Giacomo Beltrami who made the trip in 1823. He found the scenery and towering bluffs comparable to the beauty of the Rhine River. [4]

When Henry Schoolcraft documented the St. Croix River in 1832 for the U.S. Government, the river truly joined the ranks of the picturesque rivers of the world. "Its banks are high and afford a series of picturesque views," he wrote. In 1837, Joseph N. Nicollet, a French expatriate, followed Schoolcraft's path exploring and mapping the Northwest Territories. He, too, was struck by Lake St. Croix's beauty. "The shores are rugged and steep, interrupted by lovely, sheltering coves," he related. "The shallows are plentiful. It is indeed a picturesque river." [5]

The first person, however, to recommend the Upper Mississippi Valley to tourists was George Catlin, a self-trained artist from Philadelphia. Catlin's ambition was to visually record North American Indians in their natural environment before they "vanished." In 1835 and 1836, he ventured into the Old Northwest Territory to record the Sioux Indians. Catlin was so enamored by the country that he encouraged a "Fashionable Tour" of a steamboat trip from St. Louis to the Falls of St. Anthony. He wrote:

This Tour would comprehend but a small part of the great, "Far West;" but it will furnish to the traveler a fair sample, and being a part of it which is now made so easily accessible to the world, and the only part of it to which ladies can have access, I would recommend to all who have time and inclination to devote to the enjoyment of so splendid a Tour, to wait not, but make it while the subject is new, and capable of producing the greatest degree of pleasure. [6]

Many adventuresome travelers responded to Catlin's recommendation and began to take fashionable tours of the Upper Mississippi River. In 1837, the widow of Alexander Hamilton, Elizabeth Schuyler Hamilton, took the tour to Fort Snelling from the Falls of St. Anthony. She, of course, was given a royal welcome by the soldiers at the fort. When she returned to the East, she gave her stamp of approval for the "Fashionable Tour." It was, however, more the artists of the period who painted the Upper Mississippi Valley that enticed crowds to come here. In 1839, John Rowson Smith and John Risley painted a panorama of the Upper Valley, with which they then toured the country. The panorama was invented in England by Robert Barker in the latter half of the eighteenth century. There were several huge canvases done of landscapes. To transport them the canvases were rolled up into scrolls. These scrolls were then presented to the public by unrolling them in order one at a time or by displaying them in their entirety as a cyclorama. In the summer of 1848 Henry Lewis painted a panorama of the Mississippi between St. Louis and Fort Snelling that included scenes of the St. Croix. Lewis's painting "Gorge of the St. Croix," the first steamboat landing in the Dalles, and "Cheever's Mill," the beginnings of St. Croix Falls, were twelve feet high and twelve hundred yards long. His completed work of the Mississippi from the Falls of St. Anthony to New Orleans took up 45,000 square feet of canvas. Within a decade at least eight to ten panoramas of the Upper Mississippi toured the country. [7]

Honeymooning couples, small parties, and even groups of a hundred or more, soon made traveling the Upper Mississippi River a popular pastime. Some even chartered their own boats to avoid the immigrant throngs and freight stops common on the usual steamboat runs up river. Tourists came from as far south as New Orleans, and when rail service reached the Mississippi from Chicago, Pittsburgh, New York, Boston, and even Europe. Artists and writers found the region inspiring and prominent politicians and journalists, such as Millard Fillmore and Thurlow Weed of New York, as well as other dignitaries made the Upper Mississippi an important stop on their travel itineraries. River towns made them feel like honored guests by welcoming them with gala receptions. It was the rare exception for a traveler up the Mississippi not to be struck by the beauty and grandeur of the scenery both by day and night, and to be fascinated by the first-hand glimpse of Indians in their traditional life. [8] "Indian Watching" was a unique attraction of a trip up the Upper Mississippi and St. Croix River and could be done in "safety." A Dubuque newspaper advertised the trip as a "convenient and certain" way to watch Indians living in their native world. [9]

During the summer of 1849, the travel writer Ephraim S. Seymour of New York State made his "Fashionable Steamboat Tour" of the Upper Mississippi River. He followed the usual path of tourists by starting in St. Louis. He made a stop in Galena and then traveled up river to Fort Snelling and the Falls of St. Anthony. Unlike other tourists who stayed on the Mississippi, Seymour ventured into the St. Croix Valley and set about collecting information on Indians and lumbering as well as describing in detail the scenery from the Willow River to St. Croix Falls. In 1850, he published Sketches of Minnesota, the New England of the West, which introduced the scenic splendor of St. Croix Valley to the American reading public. Seymour was also the first to promote the healthful benefits of the climate from ills such as ague, which plagued more southern climes, as well as consumption. In his book, Seymour related an encounter he had with an old friend from Galena whose health had been impaired by repeated attacks of cholera. The friend hoped a trip up river to Minnesota might restore his health. "A few days spent in sporting and fishing among the brooks, rivers, and lakes of this bracing climate," Seymour proclaimed, "had rendered him quite robust and healthy." And he advised that, "Such excursions might be recommended to many invalids, as far superior to quack medicines and expensive nostrums." [10]

During the 1840s northerners began to lure southerners away from the lower latitude resorts that they had patronized, such as the Virginia Springs and the Harrodsburg Springs of Kentucky. Some venturesome southern residents had also escaped from the oppressive heat of the South into the Hudson Valley and Niagara Falls. In 1842, Daniel Drake wrote The Northern Lakes: A Summer Resort for Invalids of the South that encouraged southerners to explore the Great Lakes region aboard ship. Drake claimed that by coming north of the 44 degree line of latitude one could escape "the region of miasms, musquitos (sic), congestive fevers, liver diseases, jaundice, cholera morbus, dyspepsia, blue devil and duns!" The gentle rolling of the boat and cool lake breezes, he claimed, could cure hysteria and even hypochondraism. But before the era of widespread rail linkups, the Great Lakes were not easily accessible to those in the South. However, the Upper Mississippi River's "Fashionable Tour" was an attractive alternative with all the same healthful benefits. [11]

By the 1850s, the St. Croix attracted its share of travel writers and artists. In 1852, Edward Sullivan published Rambles and Scrambles in North and South America that described his adventurous canoe trip down the Brule and St. Croix Rivers. And in 1853, Elizabeth F. Ellet traveled up the St. Croix in the comfort of a side-wheeler steamboat with thirty staterooms to "explore" the frontier. Her explorations resulted in the travelogue, Summer Rambles in the West, which eloquently described in picturesque terminology the scenery of the Dalles and the Lower St. Croix Valley. She wrote of the Dalles:

Within a short distance of the termination of our voyage, a scene presented itself which nothing on the Upper Mississippi can parallel. The stream enters a wild, narrow gorge, so deep and dark, that the declining sun is quite shut out; perpendicular walls of traprock, scarlet and chocolate-colored, and gray with the mass of centuries, rising from the water, are piled in savage grandeur on either side, to a height of from one hundred to two hundred feet above our heads, their craggy summits thinly covered with tall cedars and pines, which stand upright at intervals on their sides, adding to the wild and picturesque effect; the river hemmed in and overhung by the rocky masses, rushes impetuously downward, and roars in the caverns and its worn by the action of the chafed waters. These sheer and awful precipices, mirrored in the waters, are here broken into massive fragments, there stand in architectural regularity, like vast columns reared by art; or some gigantic buttress uplifts itself in front of the cliffs, like a ruined tower of primeval days. [12]

Through the 1850s and into the 1880s, the St. Croix attracted local artists well versed in the picturesque. Robert Sweeny was a St. Paul pharmacist turned artist. In 1858, the Minnesota Historical Society commissioned him to paint flowers, plants, and Indian artifacts. He then turned his attention to the St. Croix and painted in a documentary-like fashion the lumber mill sloughs at St. Croix Falls, the wood arch bridge over the river at Taylors Falls, and Indians coming ashore on Lake St. Croix, and the Dalles. His paintings and sketches depict the picturesque qualities of the wilderness. Augustus O. Moore followed Sweeny. His sketches aimed to show that in the St. Croix Valley man and nature could live harmoniously. Another artist of the St. Croix was Elijah E. Edwards who was principal of the Chisago Seminary, as well as clergyman, professor, and writer. Many of his painting and sketches were of the Dalles with an eye for light and romantic views, but they also included sketches of the other rivers and water falls in the valley. Many of these paintings and sketches can by found in the Minnesota Historical Society collection. [13] While these artists recorded and interpreted the St. Croix River, their influence only extended to the local region in attracting visitors.

By the mid-nineteenth century many towns along the river, such as Prescott, Hudson, Stillwater, Osceola, and Taylors Falls provided hotel accommodations for both new settlers and some venturesome tourists. Tourism in the St. Croix Valley got a boost from the Twin Cities when John P. Owens, the editor of the St. Paul Minnesotan, took an excursion on the steamboat, Humbolt, in 1853. "The little Humbolt is a great accommodation to the people of the St. Croix," he wrote. "She stops anywhere along the river to do any and all kinds of business that may offer, and will give passengers a longer ride, so far as time is concerned, for a dollar, than any other craft we ever traveled upon." The boat graciously stopped at Marine Mills to allow its hungry travelers to lunch at the Marine House. Owen also stopped in Taylors Falls and made an assessment of this town's accommodations. "This Chisago House, is better furnished, and as well kept — barring the inconvenience of having no meat and vegetable market at hand — as any house in St. Paul, St. Anthony, or Stillwater," he wrote. "We never hated to leave a place so much in our life, when absent from home." [14]

By the mid-1850s, the St. Croix Valley had a good introduction to the traveling public. Minnesota, however, courted tourists more aggressively to its "Land of Ten Thousand Lakes" than did Wisconsin. Therefore, the valley remained off the beaten path for most tourists. As early as the 1850s Minnesota was determined to create recreational retreats that could rival eastern resorts, such as Saratoga Springs in New York State. Many hoped it would become the playground of the wealthy. Minnesota historian Theodore Blegen has written that tourism in Minnesota began with the establishment of journalism in the territory. "Every newspaper was a tourist bureau," he claimed. James M. Goodhue, the editor of the Minnesota Pioneer, was a leading booster of the recreational attractions of the territory. He made appeals to residents all along the Mississippi to escape the epidemics of cholera and malaria that plague southern climes for the healthy air and cool breezes of the North Country. "'Hurry along through the valley of the Mississippi, its shores studded with towns. . .flying by islands, prairies, woodlands, bluffs — an ever varied scene of beauty, away up into the land of the wild Dakota, and of cascades and pine forests, and cooling breezes.'" [15] John W. Bond, the premiere pamphlet promoter for Minnesota, wrote in 1853 "we have springs equal to any in the world." Rather than lure easterners, however, the ease of travel up the Mississippi made the target audience southerners. "Gentlemen residing in New Orleans can come here by a quick and delightful conveyance," Bond explained, "and bring all that is necessary to make their living comfortable in the summer months, and a trifling expense. For a small sum of money they can purchase a few acres of land on the river and build summer cottages." Bond intended to promote the Falls of St. Anthony, which he believed would "rank with Saratoga, Newport, and the White Mountains in New Hampshire. [16] In 1854, Earl S. Goodrich, the editor of the St. Paul Pioneer, beckoned southerners to the cooler, more refreshing northern retreats with biblical allusions. "Miserable sun-burned denizens of the torrid zone," he wrote, "come to Minnesota all ye that are roasting and heavy laden and we will give you rest." [17]

Travel writing, art, and real estate promotion all blended together in the effort to highlight Minnesota. By the late 1850s, Minnesota's beautiful lakes and streams were painted by Edwin Whitefield. Whitefield had also done landscapes and residences in the Hudson River Valley and the Mississippi River. By 1856, his travels brought him to St. Paul. As an artist and newly established land speculator, Whitefield captured the beauty and promoted Minnesota lakes and land through his paintings. Within the next few decades many tourists left the fashionable river tours and explored a Minnesota where ghosts of Indians and explorers still lingered. [18]

Despite its scenic beauty, however, the St. Croix was primarily a working river. The only means of travel was by steamboat, and what boats plied its waters were not luxury crafts, but packets and freight boats carrying supplies, livestock, export items, and pioneer settlers. The St. Croix Boom north of Stillwater also hindered the free flow of river traffic, as did the seemingly endless stream of logs floating down river. By summer's end the log run was finished, but the warmer, drier season lowered the water levels and exposed sandbars and narrower channels making excursions more difficult, but not impossible. In August 1859, an excursion steamer disembarked from Stillwater with thirty-five to forty citizens aboard. The Kate picked up more passengers at Marine and Osceola bringing its number to nearly a hundred. For the occasion, the boat was decorated with banners and evergreens. Although it left early in the day, the steamer did not reach the Dalles until the following morning due to "unavoidable detentions on account of the low stage of the water and heavy freight," and was hung up on bars. Apparently the passengers were not very put out by the long trip as the delay was "amply atoned for, in the privilege of passing through the "Dell' just as the sun was peeping over the mountains and dispelling the most beautiful mist and spray from that most beautiful and romantic spot." [19]

Despite the problems for travel on the St. Croix, the towns along the water still enthusiastically planned for and promoted their attractions, hoping to cash in on tourists venturing into the Old Northwest. In 1857, the four-story Sawyer House was built in Stillwater. It was considered the largest and finest hotel in the Minnesota Territory. Its "spacious rooms for social events made it one of the outstanding hostelries in the development of Minnesota." [20] Summer cottages were planned for the shores of Lake St. Croix. "The day is not far distant," claimed The Messenger, "when nice cottages. . .will reflect their white and dancing shadows from the bosom of Lake St. Croix." In June 1857, the St. Paul Advertiser gave Marine a boost claiming, "to the invalid, the pleasure seeker, as well as the sportsman, no place affords more ample inducements for sojourn and recreation." [21] In 1859, Stillwater welcomed regional visitors to its Fourth of July festivities. The steamer Itasca brought visitors from St. Paul and other stops along the Mississippi. The passengers enjoyed the annual parade, a German Singing Society, and tumblers from the Turner Society. After a cold supper in the armory, the visitors enjoyed a ball at the Sawyer House until the whistle from the boat summoned them for their late night journey home. [22]

Slavery and the Civil War put a damper on tourism in the late 1850s and early 1860s. While outright abolitionism was not much of a force in Wisconsin or Minnesota, "Free Soil, Free Labor, and Free Men" was. In the summer of 1860, a Mississippi slave owner vacationing at the popular Winslow House in St. Anthony brought along a slave woman named Eliza Winston. Winston had apparently been promised her freedom, and once on free soil she gained the support of an abolitionist and petitioned the Minnesota court for her release from bondage. The court sided with her and granted her request with no challenge from her master. Anti-abolitionist sentiment, however, had been aroused whereby a mob proposed to send Winston back to her master and tar-and-feather the abolitionist who aided her. The Undergrounded Railroad whisked her to Canada and the matter was legally ended. Hotel owners, however, feared the loss of southern tourists' patronage if they risked losing their slaves if they brought them along. The Stillwater Democrat warned that the "'intermeddling propensities of Abolition fanatics' would keep nearly a hundred of wealthy Southerners and the Negro servants from spending the summer along the shores of Lake St. Croix." But by the next spring the war had started and southern visitors stopped coming. [23]

While the Civil War brought a halt to the tourist trade, the local population found the river a delightful break from their daily toils. For many pioneers, a steamboat trip along the St. Croix was their first opportunity to view the panorama of the valley. "This was our first visit to the Upper St. Croix," wrote a member of an excursion party in 1859, "and we must admit that all our pre-conceived ideas of the beauty and grandeur of the Valley, fell far below the reality. To those fond of the wild and beautiful in Nature, we know of no place, East or West, where such a taste can be more fully gratified than in the vicinity of Taylor's Falls." [24] In August 1856, the editor of the Prescott Transcript rounded up a party to take a steamboat excursion trip up to Taylors Falls. "The weather was delightful," he reported, "the boat [was] provided by Capt. Martin and his obliging assistants with every possible accommodation, and all were in fine spirits. . .The scenery along the lake and river was observed with a pleasant interest by the party, to the most of whom it was new." The group was also intrigued "by the antics of some forty or fifty thousand big sturgeon that gave us a grand fancy dance around the boat as we passed along. . .They present one of the most interesting piscatory sights imaginable." [25] The abundance of game along the river not only provided sustenance for the first pioneers, but also supplied the sportsman with a wide variety of birds, animals, and fish. From its earliest days of settlement sportsmen were also attracted to the St. Croix Valley. In his 1849 book, Sketches of Minnesota, Seymour wrote to his nationwide audience that the lower St. Croix Valley was "a fine country for sportsmen. . .Deer are killed here in great numbers. . .The bear and the large gray wolf are often seen. Wild geese and ducks resort here in great numbers...The best trout fishing in the northwest is said to be on the Rush River. They are caught in immense quantities, not only with hooks, but also with scoop-nets." Seymour also noted that the St. Croix had groves of trees "alive with pigeons, which were constantly rising from the ground in large flocks." The birds he referred to are the now extinct passenger pigeons that once crowded midwestern skies in the nineteenth century. [26] "The country surrounding our city is filled with game," boasted the St. Croix Union in 1854. "Not infrequently do we hear a sportsman relate the experience of deer shooting. . .or what sport they had in ‘bagging' a drove of prairie chickens. Deer are so plentiful. . .Our hunters have become so well acquainted with the habits of this animal and so adept in the use of the rifle that it is a matter of no common occurrence to find their tables well supplied with venison. . .We have a great many streams filled with [trout], and it is fine sport for those who are disposed to engage in it." [27]

One unusual method to hunt deer was created by a Dutch hunter named Otto Neitge. In 1853, Neitge bought land in what is now Deer Park. Within five years he built a trap to catch deer with an eleven-foot palisade of posts. Deer could jump in but they could not get back out. Once a herd of one hundred became trapped inside the park, Neitge shot and slaughtered the annual increase, which he then sold in St. Paul and to Fort Snelling. Neitge also tried to do the same with bears, but they proved too troublesome. In 1874, the North Wisconsin railroad passed through Deer Park, and many people discovered Neitge's deer hunting secret. He developed a reputation as "a low, cowardly" sportsman who "shot, from between the poles of the stockade, many of the captive deer." This prompted Neitge to abandon this form of hunting, but his park lives on as a village name. [28]

In the 1850s, between Marine and Taylors Falls was an area valley residents called in the 1850s the "bear hunting ground." The innkeeper at the Marine Mills Hotel loved to serve this local delicacy to his visitors. From time to time a "General Bear Hunt" was organized out of Prescott for a two-day excursion for "all who desire to share in the sport." An amateur poet from Hudson enticed hunters with the following:

Come on then, ye sportsmen with high boots, rifle and blanket, and I will shortly conduct you to the forests where my forefathers, as they chased the swift elk and the huge black bear, would proudly exclaim,

No pent-up willow huts contain our powers,

But the unbounded wilderness is ours. [29]

Since winters were so cold and long, many hearty souls took to winter sports. In the winter of 1863, the Stillwater Messenger announced, "Members of the Skating Club and all others are invited to call and examine our stock of skates, skating caps, hoods, nubias, sontags, balmoral skirts, balmoral shoes, gloves, mitts, &c." [30] A year later the paper reported, "The warm days and cool nights we have had lately have made the skating good upon the lake, and large crowds are enjoying the sport during this pleasant weather." [31] Springtime brought out the baseball enthusiasts of the St. Croix Baseball Club. [32]

When the war was over, the St. Croix Valley returned to the national scene. Famed journalist Horace Greeley visited the St. Croix Valley in 1865. He was not only impressed by its wheat production, but also by its healthy climate, and recommended the area for those plagued by ague and chronic coughs. The Stillwater Messenger quickly echoed these sentiments. The paper even joined in the exaggerations that often accompanied the literature written about the health benefits of the area. "Pine emits an odor peculiarly healing and highly beneficial for invalids, hence it is no uncommon thing for small parties to take up their quarters in the wilderness, and spend the winter there with numerous gangs of lumbermen." [33] Consumption suffers, in particular could find relief in the pineries of the upper St. Croix. A poem was even written about the health-giving pine trees:

For health comes sparkling in the stream

From Namekagon stealing;

There's iron in our northern winds,

Our pines are trees of healing. [34]

Health seekers from the South and East were also enticed back to the region after the war by handbooks, such as Tourists' and Invalids' Complete Guide and Epitome of Travel. [35] By the end of the 1870s southerners began to come to the St. Croix again in noticeable numbers. "Capt. Jack Reaney came up on the steamer Knapp Tuesday, and has been rusticating in the upper St. Croix Valley for a few days," wrote the Burnett County Sentinel. He informs us that the tourists from the south are coming up in large numbers, and many of them find their way to the St. Croix river." [36]

By the 1860s, a new medium was developed that was able to portray the unique scenery of the St. Croix to a wider audience -- the stereograph. Between the 1860s and 1880s making and selling stereographs of the St. Croix became a profitable business. The most noted photographers of the St. Croix in this period were William Illingworth, Charles A. Zimmerman, William Jacoby, and Benjamin Upton, and Joel E. Whitney. Whitney was the first major commercial photographer in Minnesota. While he began his business taking daguerreotypes of people, in the 1850s he brought his camera along on a twenty-five mile hike around St. Paul and St. Anthony taking eighty landscape pictures. By the 1860s, the demand for landscape photographs became the "bread and butter" of commercial photographers, and the St. Croix Valley was included in the search for these picturesque and sublime pictures. [37]

In 1875, John P. Doremus of Patterson, New Jersey began photographing the river as part of a "floating gallery" on a boat that was "a little palace itself." "He started out from St. Anthony over a year ago," related the Lumberman, "with the intention of taking views along the Mississippi and its tributaries down to New Orleans." The paper expressed appreciation for his carefully considered photos. "He takes it leisurely and does his work in fine shape, the views he has of the St. Croix being the best we have ever seen." The charms of the St. Croix were now visually documented to attract more tourists looking to escape the oppressive heat, humidity, and illness of the lower Mississippi. [38] The St. Croix Valley's fame spread further when in 1885 Eastman's roll film was developed. In 1900, Kodak's Brownie camera made photography easier and cheaper for visitors to the St. Croix to share their experiences with friends back home. [39]

Figure 30. Steamboats provided tourists with easy access

to the Upper Mississippi Valley and allowed tourism to begin as early as

the 1830s and 1840s.

Railroads Promote Tourism and the Resort Industry

While the visual fame of the St. Croix Valley spread throughout the latter half of the nineteenth century, the tourist business on the St. Croix River took off in the 1870s ironically with the arrival of the railroad. Unfortunately train travel ended the "Fashionable Tour" by steamboat up the Mississippi. Taking a steamboat for other than a day trip came to be seen as "old fogyish." Steamboat day trips, however, remained the most attractive and unique tourist attraction in the St. Croix Valley. Boat owners realized early on they could enhance their profits by offering not only regular transportation for residents and newcomers, but also offer pleasure excursions. Inexpensive fares encouraged the locals to take advantage of the opportunity for a day trip into the beauty of their river valley.

With connections to St. Paul, Milwaukee, and Chicago local steamboats enjoyed a fairly steady stream of passengers. The trains brought visitors to the steamboat landings; and after a trip upriver from Hudson or Stillwater to Taylors Falls, tourists made the return trip by train when railroad connections were made in 1880. Stillwater's Cornet Band added to the gaiety of these outings. Steamboat owners also made moonlight cruises available for the more romantically inclined. Excursions provided church, social, and work groups trips with a more relaxed form of social interchange. For example, in June 1875 firemen from Red Wing, "accompanied by their ladies" boarded the steamer James Means for a trip up to the Dalles. Not only did they enjoy the scenery, but joined the Stillwater fire department in some social recreation. "In the evening the boat laid at the levee several hours," related the Stillwater Lumberman, "and allowed the firemen an opportunity to be entertained by the chief and members of the Stillwater department." [40]

Those who chose to stay in "the charmingly old-fashioned" town of Taylors Falls found comfortable accommodations at the local hotel. There they were "gladly welcomed and hospitably entertained." The president of the town council, L.K. Stannard, gave welcome addresses to St. Paul excursionists. Others found lodging in towns down river before they began their return home by rail. [41]

In 1877, the St. Louis, Minneapolis & St. Paul Short Line distributed a pamphlet entitled, The Summer Resorts of Minnesota: Information for Invalids, Tourists and Sportsmen. Train travel was promoted as fast and safe as well as being furnished with all the modern and luxurious conveniences. "While the summer resort business in the Northwest may be said to be yet in its incipient stage," related the railroad company, "there is but little more to be desired in railway service than is already furnished by the favorite line known as the 'ST. LOUIS, MINNEAPOLIS & ST. PAUL SHORT LINE.'" They offered reduced fares for anyone who made connections from other cities in the country at St. Louis. "There are but few people who have passed the summer months in Minnesota who will not agree with us in saying that there is no country in the world which offers so much that is pleasant and attractive to the tourist as that included within the boundaries of Minnesota." One of the chief selling points for a vacation in Minnesota was the weather. "The summer breezes that sweep across our wide prairies and through our great forests, bearing the perfume of wild flowers and aromatic pines, are laden with a magical tonic which quickens the pulse, and imparts new vigor to the enfeebled frame," wrote the promoters. "All the surroundings of our rural homes exert an influence for good, and attract the invalid to unwonted exercise in the open air, which creates an appetite for substantial food, and strengthens the digestion." [42]

The railroads also put the towns along the St. Croix on the entertainment circuit. In 1877, Stillwater businessmen persuaded P. T. Barnum to bring his circus to town. Other circuses followed such as the PA. Older's Museum, Circus, and Menagerie, and the W.W. Coles' Great New York and New Orleans Circus, Menagerie, Museum, and Congress of Living Wonders. Wealthy lumbermen also courted popular entertainers of the nineteenth century, such as Jenny Lind, Ole Bull, Adeline Patti, as well as the culturally influential Chautauqua Meetings. [43]

New guidebooks catered to this new class of travelers. They continued to stress many of the same themes of the earlier period. "Romantic beauty, historical incidents and legendary lore contributed towards making the Valley of the St. Croix River not only very interesting to the tourist," wrote guidebook author William Dunne, "but exceedingly valuable to students of either events or nature. Here within an hour's ride of the two leading cities of Minnesota, is a miniature Hudson, excelling, in some features, that famous river of the East. Along its shores fierce Indian battles have been fought, and its fertile, picturesque valley contains attractive cascades and waterfalls that rival the renowned ‘Falls of Minnehaha.'" Throughout the guide, Dunne recounted the basic history of the St. Croix Valley of Indians, explorers, missionaries, fur traders, lumbermen, and settlers to stir the imagination and conjure ghosts of yesteryear. "We traveled past battle grounds and fishing nooks, past the old home of the deer and the moose, past where Poor Lo held full sway but a generation ago and we had enjoyed the day." Interestingly, once they were pushed aside, Indians were portrayed as romantic and exotic creatures rather than threatening savages. [44]

The guidebook also contained poetic descriptions of the landscape. "The sunlight stole through the embowering trees of the glen just enough to brighten into sparkling crystals the falling waters of Osceola Creek," wrote Dunne, ". . .a very beautiful gem of nature." Of the Dalles he wrote, "Shadows from jutting rocks and tall trees fall upon the water in strange contrast with the sun-brightened portions where the tree-topped rock walls of the Dalles are distinctly reflected in the seemingly quiet stream, yet, of quietness, ‘tis but the semblance born far below the glassy surface. Between these two walls the river flows and eddies with depth and force." His description of Devil's Chair was especially evocative, "From a height of eighty feet his Satanic Majesty could view the whole extent of the beautiful landscape. Upon the footstool of his chair he could rest his weary feet or stand and address his kindred spirits of the Northwest during his councils with them." Dunne tempted the adventurous spirit of his readers with the suggestion that there were still the possibilities of new sights to discover. "In the attractive glens and curious ravines along the sides of the St. Croix there are yet to be found cascades and other scenic beauties that will, in the near future be noticed and highly appreciated." [45]

One notable side attraction a mile and a half from Stillwater was Fairy Falls, "a quiet but pretty work of nature." In 1880, William Dunne described the descent of the falls. "The water, coursing along to the shelving ledge of rocks, dashed down, in an almost unbroken stream, to its bed below." Locals enjoyed it as a popular picnic spot. [46]

While trains brought visitors to the St. Croix, they also made it possible for tourists to venture away from the river. Many discovered the charm and beauty of the Chisago Lakes region on their return trip by train from Taylors Falls. Dunne noted, "The excursionists were pleasantly surprised to see such delightful scenery in the Chisago lake region, through which they passed." [47] The advantage of the lakes over the river was that they could be enjoyed throughout the summer, free from the sights and sounds of logs and crude lumbermen on the river. Although many Swedish immigrants farmed the area, the lakes themselves remained sparsely populated throughout the nineteenth century even though the banks were largely prairie. After 1868 when the St. Paul-Duluth railroad skirted the western portion of Chisago County, towns such as Center City, Lindstrom, Forest Lake in Washington County, and St. Elmo Lake, became summer meccas for vacationers from the Twin Cities. Trains made frequent stops at Forest Lake to refuel thus making it easy for visitors to attend to business in the city and return to the rejuvenating lakes region with regularity. Railroads were not just anxious to promote the resort industry. They also hoped people would decide to buy a permanent house along the route. Before there were any permanent structures, early lake visitors pitched tents. When a certain area proved its popularity, enterprising businessmen started to build resorts. Forest Lake, for instance, became a resort city complete with prominent hotels, such as the Marsh and the Euclid. Yet, tents remained popular among the less well to do. Tents also made it possible for large parties of friends, church groups, social clubs, or businessmen to enjoy the great outdoors together without the expenses incurred in resorts and hotels. [48]

Lake Elmo also emerged by the late 1870s as a premiere vacation spot. It was halfway between St. Paul and Stillwater and was promoted by the St. Paul and Sioux City railroad. Many of St. Paul's fashionable class enjoyed boating, picnicking, and dancing under the stars. [49] Dunne's guidebook described Lake Elmo as "A handsomely situated body of water, such a delightful place as we would expect to find in the undulating wooded district. . .Its rustic seats and shaded walks, its neat pavilions, its boating and fishing make it a popular excursion resort for societies and schools." Elmo Lodge was equipped with "every modern accommodation and in the highest sense ‘cares for' its guests." Its "up to the times" comforts attracted repeat guests. [50]

White Bear Lake north of the Twin Cities and equidistant from Stillwater attracted those cities' elites. Vacationers started coming to the lake as soon as a road was built in the early 1850s from St. Paul. These seekers after refreshing summer breezes arrived by horse or carriage in just two hours. In 1857, an elegant Greek revival hotel was built to accommodate the fashionable, and less pretentious lodges housed more modest clientele. By the Civil War White Bear Lake, straddling Washington and Ramsey Counties, was a popular resort welcoming holiday and weekend pleasure-seekers and sportsmen. Once the railroad came after the war, the twenty-minute train ride turned White Bear Lake into a summer home retreat. It is "one of the brightest gems in the circle of lakes surrounding St. Paul and Minneapolis," wrote the St.L, Minn. & St.P. promotional pamphlet. "White Bear is the oldest summer resort in the State, and consequently, is far advanced in many of the conveniences required by fashionable people who do not care to indulge in the wild and sometimes inconvenient modes of life found at our less developed watering places." [51] Even Mark Twain wrote about White Bear Lake in his Life on the Mississippi. "There are a dozen minor summer resorts around about St. Paul and Minneapolis," Twain related, "but White Bear Lake is the resort." [52] It possessed " the largest fleet of sail boats and yachts to be found in Minnesota," wrote Dunne. "On the evenings of the "Regatta" and ‘open air' concerts, White Bear Lake assumes the appearance of a gala night at Manhattan Beach, more than of what is generally expected at a suburban summer resort." [53] By 1885, Northwest Magazine enthusiastically endorsed White Bear Lake as a resort area. "White Bear has pavilions, club houses and pleasure boats galore. But it has never become noisy and Coney-Islandised," the magazine noted. "It remains today a place for rest and pleasure rather than rioting and boisterous sports. It is fashionable without being fashion-ridden; popular and populous without being crowded." [54]

In 1884, the resort industry reached Lindstrom when Ida Van Horn Elstrom opened her Lake View House on the peninsula between the two Lindstrom lakes. Trains deposited guests at the nearby train station. When Miss Elstrom married John W. Nelson, the newlyweds changed the name to the Lake View Hotel. When the hotel burned down in 1900, the couple opened the Villa Cape Horn resort on the lakefront west of their old establishment complete with a dancing pavilion. The resort thrived well into the 1920s.

After the Nelson's success, other resorts began to appear on the local lakes. Besides the usual resort businesses, the Chisago Lakes area also attracted nonprofit camps. In 1906, the Minneapolis YMCA opened Camp Icaghowan on the eastern shore of Green Lake near Chisago City. The name of the camp derived from a Chippewa expression that meant "growing in every way." It was an apt phrase for a camp dedicated to providing disadvantaged urban boys with a week or two of summer fun. The cost was a dollar a day. Charitable Minneapolis businessmen picked up the cost. Camp Icaghowan won a special place in the hearts of the boys who summered there. The original camp lasted until World War II. After the war, the men who spent their youth there, built a new Camp Icaghowan on the Wisconsin side of the St. Croix near Amery. [55]

By 1880, fishermen and campers had made the Chisago Lakes a well-established sportsmen's locale. "Camping out at the numerous lakes with which Stillwater is surrounded is a growing practice with our citizens," noted the Stillwater Lumberman. "The practice is a good one. It is not expensive, and as a means of promoting health none better will be found. . .There are no fashionable calls to make or receive, no elaborate dressing for company. Everything is free and unrestrained. The male members of the family usually go out on the evening train or drive out. . .until the morning calls them back to business." [56]

The typical resort of this period in the north woods catered to the patterns of social interaction of the elite. They operated on what was called the "American Plan" in a largely self-contained world. There was a main lodge, where all meals and social activities took place. Lodges were usually constructed of local materials, such as logs, with a large field stone fireplace as a centerpiece. Guests slept in simple cottages. Maintenance buildings, barns, an icehouse, a small farm, and a boathouse supplied all the basic necessities to run the resort. [57] The single, family-owned cottage did not generally start to appear on the lakes until the turn of the century.

The well-advertised Minnesota resorts may also have siphoned off many potential long-term visitors to the St. Croix Valley. The St. Croix was advertised to Twin City residents as simply a day trip. "In the brief period of a single day," wrote a railroad advertisement, "the appreciative ‘sight seer' can here enjoy a variety of scenery, perhaps unequaled in America — if the world." [58] Although praising the wonders of the St. Croix River, the St. Louis, Minneapolis, and St. Paul Short Line promotional pamphlet noted that fact that the St. Croix was a working river. In 1869, 270 steamboats plied the river between Prescott and Taylors Falls. The logging companies, especially, increased the number of boats on the river. In 1878, they employed eight steamboats for rafting and towing, in 1882 there were seventy-seven, and by 1891 that number increased to 130. "Ever present among the islands and along the low shores for several miles. . .are the evidences of the vast traffic in lumber that is carried on in this valley," the promoters wrote. "The thousands of logs that lie ‘hung up' on the shores, at which gangs of men are laboring, tugging and rolling, to get them afloat in the river: the miles of booms, the vast number of piles that are driven to prevent the logs from stranding. . .the dozens of steamers for town. . .and the numbers of men employed, all combine to form an array of business that is not seen in the ordinary routes of travel elsewhere in the west, and probably not in the world." The pamphlet promoted the Upper St. Croix more for sportsmen where outfitters and guides were ready to assist that type of traveler rather than cater to the fashionable. [59]

The St. Croix Valley also faced competition from the growth in recreation to the south. Between 1873 and 1893, southern Wisconsin also experienced its own tourist boom that attracted residents from Chicago and other southern climes. In 1869, Colonel Richard Dunbar claimed that the Waukesha mineral spring had cured him of diabetes. Dunbar proceeded to organize the Bethesda Mineral Spring Company that promoted Waukesha as the "Saratoga of the West." The Chicago and Northwestern Railroad serviced the town and soon Waukesha had thirty hotels and dozens of boarding houses that catered to summer visitors. Spas had become so popular during this period with the middle class that nearly every spring bubbling out of a limestone substrata was being promoted as a spa, such as Madison, Beaver Dam, Sparta, Palmyra, Beloit, and Appleton. [60]

The St. Croix Valley did not sit idly by while watching Minnesota and southern Wisconsin develop into resort destinations. In 1873, in anticipation of a boom in tourism Ebenezer Moore embarked on a plan to turn Osceola into the "Saratoga of the West," and invited the public to his St. Croix Mineral Springs. The springs were located two miles south of Osceola near Buttermilk Falls. Moore hoped both tourists and health seekers would flock to its "healing" waters. Before his vision was realized, however, Moore sold his interests in the springs to a partner from Eau Claire. In the spring of 1875 the new owners laid a foundation for a "mammoth hotel" aptly named the Riverside Hotel. "Messrs. Stephens, Williams & Fletcher, the proprietors of this property, are determined to make the springs a popular resort for both invalids and pleasure seekers," wrote the Lumberman. [61] "The location selected for the hotel is a delightful one, overlooking the river and affording a picturesque view of the surrounding country." The dining room seated two hundred guests, and the grounds were complete with a croquet course, a trout pound, a deer park, and a half-mile circular racetrack. A hydraulic pump brought spring water into all parts of the hotel. "It promises to become on the most attractive summer resorts in the Northwest," boasted the Lumberman. This dream, however, never materialized. Although medical men endorsed the healthfulness of the waters, tourists never patronized the hotel. The year 1873 was also one of a financial panic. By the middle of the decade eastern and Midwest railroads experienced labor turmoil. Higher rates and strikes tied up everyone's travel plans and financial hardship reached every part of the country that relied on rail service. In 1885, the under-used hotel burned down. [62] In 1903 another entrepreneur experimented with a health elixir called "Osce-Kola, which was a concoction of spring waters, fruit juices, celery, and cola. The mineral springs, however, did not sell in this version either. [63]

Although tourists from more distant places did not venture so far north or stray from Minnesota's lakes, this did not stop residents along the river from recognizing and enjoying the pleasurable opportunities of the St. Croix. In the mid-1870s Stillwater established a boat club, as did many other towns along the St. Croix and Upper Mississippi. Stillwater's club proved to be a formidable challenger. "The character of the lumber business transacted at Stillwater naturally brings into action the full muscular force of the operatives engaged therein," boasted the Lumberman. "Here we have men who are continuously in the boat and at the oars. . .[who] are required to operate against wind, current, and all contending influences." The Stillwater club was so successful at beating local comers; they decided to challenge the Red Wing team. "The case with which they gained each successive victory emboldened them to believe that they had but to enter their shell and take the money, prize, and championship from any club that might choose to contest their skill." Many excursionists from the area made the trip by steamboat to watch the races. The Red Wing Team, however, resoundingly defeated the Stillwater club. They and their supporters took their defeat in good humor and enjoyed the return river journey home. [64]

St. Paul residents continued to patronize the St. Croix River and the Dalles during the second half of the nineteenth century because it was so close. In June 1877, a group from the Twin Cities arrived in Stillwater "on the natty little steam yacht Lulu. . .and were highly pleased with the romantic scenery of Lake St. Croix." On their way to the Dalles passengers enjoyed "the witty sallies elicited by the demonstrations of the river men, who lustily cheered as we passed them, waving their hats and handkerchiefs, and tossing up their pikes." The yacht also had to maneuver its way among "the great quantity of floating logs in the stream." The Lulu then remained at Taylors Falls where it picked up passengers from the St. Paul train, took them to see the Dalles, and then returned them when the evening train departed for the Twin Cities

One way to pass the time on the long, slow steamboat trips was to shoot geese from the boiler deck, which entertained both passengers and crew. Captain O.F. Knapp, of the steamer Enterprise, first introduced the practice in the mid-1860s. The sport caught on and by the 1870s and 1880s parties chartered steamboats for these hunting expeditions. [65] Southern tourists were especially enamored with this unique form of hunting. "Frequent notice has been made in these columns," wrote the Stillwater Lumberman, "of the rare sport furnished on the St. Croix by hunting geese with a steamboat. The time has now arrived for the full enjoyment of this sport and it is daily being indulged in." The paper provided a colorful description of how the sport was done. "As soon as the boat was headed down the lake a bulkhead was constructed around the forward guards of the lower deck so that the hunters could, if they choose, shoot from that place unobserved. Screens were constructed of blankets and placed around the railing in front on the boiler deck for the same purpose. All these precautions are rendered necessary as a boat cannot get within gun shot if any person's body or head is visible to them." [66]

Figure 31. The Devil's Chair in the Dalles was just one

of the picturesque sites that insured the establishment of the

Interstate Park. From Outing Magazine, March, 1890.

Hunting and Fishing for Sport

Besides geese, "Duck shooting on the St. Croix above Marine [was] the fashionable amusement," wrote the Stillwater Lumberman in 1877. [67] And in 1879 the Burnett County Sentinel noted, "Hunting and fishing parties are the order of the day in this vicinity." [68] "A party of 5 passed through here from Marine enroute for the upper Namekagon fishing and sporting," reported the Sentinel with interest and approval. [69] These comments, of course, imply that game was more than a daily sustenance requirement, but provided variety to the dinner table as well as enjoyment in the pursuit.

By the 1870s, popular sporting magazines, such as American Sportsman (1871), Forest and Stream (1873), Field and Stream (1874), and American Angler (1881), were published to encourage outdoor sports. The writings of their authors were certainly influenced by the Romantic Movement and its attitudes about nature, but they differed from earlier nature writers, who simply appreciated the splendor of the outdoors for its own sake. While the beauty of the scenery was certainly to be enjoyed, this new breed of outdoorsmen approached wildlife in a practical, utilitarian manner. It offered sport and prize catches. Beginning in the 1870s many railroads also organized hunting and fishing excursions. Some even owned their own resorts. [70]

Although the Wisconsin state legislature had established defined hunting seasons in order to protect, game, birds, and fish in 1851, by the 1870s over-hunting and the expansion of settlement made big game scarce in the Lower St. Croix. Conservationist ideas had not quite reached this frontier region. When a rare moose was spotted near Rush City in the fall of 1877, the pursuit was on. The following excerpt from the Stillwater Lumberman provides an insight into the attitudes of residents towards the sport of hunting:

A wild moose was foolish enough to call upon Frank La Suise, at that gentleman's residence. . .introducing himself to Frank's family by peering through the window of their residence. Frank not liking such familiarity, seized his gun and greeted the animal with a charge of buckshot, which caused the moose to take to the water, whence Frank followed in a canoe, blazing away at the "baste" as rapidly as he could load his gun. A broadside from Adam Dopp, who appeared on the scene, blinded the creature, so that Frank was enabled soon to dispatch it with a club. . .It was the means of furnishing a very tender article of fresh meat for our citizen's dinner last Sunday. [71]

By the 1880s, moose had even disappeared in the Upper St. Croix Valley. A killing of one was worthy of note. "A moose was killed near Clam Lake last week," the Burnett County Sentinel remarked with interest. "A very rare animal in these parts." [72] An old time settler reminisced in 1880 that the early days were his "happy days. Game was everywhere." In one fall season he had killed 130 deer, 16 elk, and 3 bears. [73] Clearly such a total exceeded his personal needs and he was engaged in market hunting — an activity that was roundly condemned by "true" sportsmen.

If moose and other big game were no longer plentiful in the north woods, fish, waterfowl, and deer still were. "Hunting and fishing at Bass Lake, Willow river and other noted points near at hand are leading sources of enjoyment" [74] In June of 1877, a fishing party from Hudson set out for the Clam River. They returned, "having caught seven hundred and fifty trout," recorded the Lumberman. [75] By the 1890s the number of fish caught was less important to true sportsmen than the size of the fish. "Last week, a Frenchman caught a sturgeon in the Namekagon river near Phipps, weighing 81 pounds," wrote the Burnett County Sentinel in 1891. "This is said to be the largest fish ever taken out of a stream in this locality." [76]

Unlike moose or other big game that were easily threatened by market hunters and habitat loss, fish stocks were easier to replenish. In 1866, the Wisconsin state legislature appointed a fish inspector. This eventually led to fish stocking in the state's waterways. In 1880, over a million brook trout were put into the streams of Wisconsin. In 1883, the U.S. Fish Commission deposited 250,000 white fish and lake trout eggs into Lake St. Croix. Sawdust that had been dumped in the river and the erosion of the river's banks by logs and upstream deforestation silted up the river and destroyed much of the natural habitat of fish. The federal government's initial interest in restocking rivers and streams was to preserve commercial fishing. Sport fishing was an indirect beneficiary of this program that kept the St. Croix and its tributaries teaming with fish. [77] In 1895, the Polk County Press bragged that, "There is no county in Wisconsin, outside of the lake Superior counties, were better, or a greater variety of fishing can be found than in Polk county. And in Polk county no better place than in the vicinity of Osceola. Within a circuit of ten miles there are fifteen lakes, and the St. Croix river, all well stocked with pickerel, bass, pike and other fish, besides three fine trout streams, well supplied with speckled and rainbow trout." The paper went on to report the size of recent catches from local fisherman. [78]

Unlike the moose, deer did not disappear from the St. Croix Valley with the retreat of the forest. Various kinds of berries flourished in the brush left in the loggers' path, which deer feasted on. Hunters in turn feasted on the deer. The importance of deer as food and sport is illustrated in the following Burnett County Sentinel article. "It is reported that there are some hunters camped just above Clam river who are hunting deer with dogs. This is against the law and they should be arrested and prosecuted." [79] Rules of sportsmanship were clearly of importance to the residents of the St. Croix Valley. Other animals were not considered so valuable. "The scalp of a lynx was brought in from Wood Lake Wednesday. They are worth. . .$3," reported the Sentinel. "There is a bounty of $6 on wolves, $3 on wild cats, and $2 on foxes." [80] This made hunting a lucrative sport that aided the farmer and settler in dealing with these pesky animals. Indians, too, often redeemed these animals for their reward.

Figure 32. Canoeists pass Angle Rock on the St. Croix.

From Outing Magazine, March, 1890.

Steamboat Excursions

Besides changes in the animal population, the late 1880s brought an end to the commercial boating industry. Residents and businesses came to depend on and prefer the year-round efficiency, comfort, and dependability of railroads. Commercial steam boating, which had once been the lifeblood of the St. Croix Valley by bringing in supplies and pioneers and then taking their produce to the world, could no longer compete against the iron horse. The river, however, did not lose its allure. If anything, its mystic grew. By the 1890s, the excursion boating business revived the "Fashionable Tour" -- at least in part. Aside from logs, the only traffic on the river was pleasure-seekers on steamboats. Although the railroads supplanted the transportation and commercial role of the river, they eagerly assisted the tourist trade by coordinating their schedules with boat excursions. A friendly rivalry developed between the towns along the St. Croix over who attracted the most excursionists. The day trip excursions offered from Minneapolis to Osceola made it the leading Soo Line city along the St. Croix. "Osceola largely leads the towns on the St. Croix," boasted the Polk County Press in October 1887. The Soo Line sold 335 excursion tickets out of Osceola that season. St. Croix Falls followed a distant second with 191 tickets sold. Marine was next with 130, and Dresser Junction sold a mere 56 tickets. [81]

With the growth of pleasure excursions, Osceola came into its own as a tourist town. It boasted that its waterfall was "unrivaled by any waterfall in the northwest." [82] For its Fourth of July celebrations the town attracted one thousand people who enjoyed a parade, a baseball game between Osceola and St. Croix Falls clubs (which Osceola won 24 to 23), and a picnic on Eagle Point Bluff, "a beautiful place for a picnic or celebration, and one of the finest groves in the valley." Other amusements visitors and residents engaged in to pass a lazy summer day were climbing a greased pole, a potato race, tug of war, cracker race, egg race, logrolling, sack race, foot race, a wheelbarrow race, and a 100-yard backward race. In the evening dances were held under the stars. [83]

In the late summer of 1888 Osceola also hosted a picnic for the veterans of the Grand Army of the Republic and their families. The town expected a thousand visitors, but threats of rain reduced the numbers to only four hundred picnickers. The rain, however, held off long enough for the usual speeches to be made, a picnic lunch served, and a late afternoon excursion made through the Dalles. "The day was pleasant but cool, and was heartily enjoyed by all the visitors," reported the Polk County Press. [84]

The next summer Osceola hosted a picnic for eight hundred Soo railroad employees. While they picnicked on Cascade Bluff, a cornet and a string band entertained them. Games and dancing followed. "A delightful day and enjoyable time was had," reported the Polk County Press. "Osceola is proving to be the most popular place on the river for railroad picnics." [85] These words were prophetic. By 1893, the town hosted one thousand railroad picnickers with the usual entertainment. [86] One interesting group that came to Osceola for a picnic in July 1891 was the Knights of Pythias, an African American group. Many people from Osceola joined them for dancing and baseball. Later they took a trip up river together. "As many white people as colored attended the picnic," noted the Polk County Press. "All danced and rode together and a real nice time was enjoyed." [87]

Figure 33. The lower St. Croix in the 1890s. Note the

numerous logs washed up on sand bars. These logs posed a major hazard

to recreational use of the river. From the State Historical Society of

Wisconsin.

The Nineteenth Century Conservation Movement and Recreation

By the 1890s, many Americans were ready for more vigorous recreation than that offered by the genteel spa resorts of southern Wisconsin. And while summers by the lake continued to attract greater numbers, touring, hiking, fishing sailing, biking, and hunting, as well as the growing popularity of baseball led many tourists to seek more adventurous outdoor challenges. The continued growth of the middle class enabled many more people to reach and enjoy the outdoors. But this also brought about a changed attitude towards nature from one of simple appreciation to the growing recognition that natural treasures needed to be protected from further development and destruction. Sportsmen were the first group to join the growing conservation movement and to lobby for the first forest reservations in the western United States. The number one sportsman and conservationist in the country was Theodore Roosevelt. Like many urbanites at the end of the nineteenth century, Roosevelt looked to hunting and fishing as a retreat from the cares of the city and an opportunity to approximate the experience of the first pioneers. By the turn of the century and into the next, "roughing it" came to be seen as a critical part of individual character building as well as an opportunity to engage in a distinctive American cultural activity. Many of the great men of the era, such as Henry Ford and Thomas Edison, enjoyed trips to the wild. By the 1920s, President Calvin Coolidge put the Brule River on the sportsman's map with his widely reported fishing trips to the region. Oddly enough many men who made their fortunes exploiting nature were among the first to build sanctuaries in wilderness areas. Factory owners and railroad men, as well as the doctors and lawyers who served them, found the St. Croix one of the least permanently spoiled havens in the Upper Midwest. [88]

Through the end of the nineteenth and into the twentieth century, recreation began to spread throughout the entire north half of Wisconsin to accommodate this new type of recreation. The Wisconsin Central Railroad enticed these more hardy travelers into the far north woods. The railroad company built its own hotel in Ashland called the Chequamegon in which it could house several trainloads of sportsmen and vacationers. In 1879, James Maitland wrote a pamphlet for the railroad called, The Golden Northwest. In it, he described not only the picturesque sights of northern Wisconsin, Minnesota, and the Dakota Territory, but also advertised the possibility for more active recreation. In 1885, the Chicago, Milwaukee & St. Paul Railway followed up on the interest in active recreation with its own pamphlet, Gems of the Northwest. In the brochure, outdoorsmen were depicted with the latest equipment in tents, fishing poles, and the like while "roughing it" in the great outdoors. [89] The formal attire sportsmen were photographed in interestingly demonstrated the elite nature of hunting during this time. Some hunters were decked out in three-piece suits complete with tie. [90]

New England states continued to exert influence in northern Wisconsin. Like wealthy Adirondack businessmen, executives in the logging and lumbering industry built lodges and estates along the Upper St. Croix and Namekagon Rivers. One example is that of the Velie Estate. The John Deere Company originally owned the two-thousand acres dating back to 1893. It was located in Douglas County, seven miles southwest of the Gordon Dam. In 1905, Velie built a twenty-four room lodge to serve as a fishing club for company officials. It included a playhouse, fish hatchery, and stable. Another sports club, most likely owned by the Farmers' Land and Cattle Company of St. Paul and the Saint Croix Timber Company, was located in an unidentified section north of the Upper St. Croix River. [91]

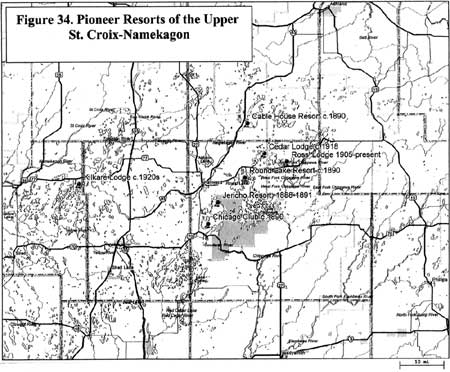

Figure 34. Pioneer Resorts of the Upper St.

Croix-Namekagon.

(click on image for an enlargement in a new window)

Establishing the Interstate Parks

The conservation movement arrived in the St. Croix when George Hazzard organized a movement to create a state park out of the Dalles area. In the late 1860s, St. Paul street builders experimented with crushed trap rock from the Dalles to use for macadam roads in the city. Hazzard, who fell in love with the river and the Dalles as a young boy, was appalled at the idea. He had arrived in the St. Croix Valley in 1857 on the steamship H.S. Allen in the evening. "Those who made the trip remember its impressions," Hazzard wrote years later. "To others it cannot be described." His love of the river and its scenic beauty grew as he served the traveling public as a general agent for railroads and steamboat lines out of St. Paul. The Dalles of the St. Croix was always high on his list of recommended visits and the grateful appreciation of tourists whom he had steered there convinced him "that in the Dalles there was great value to the States of Minnesota and Wisconsin." When the Dalles began to be dismembered for road use, Hazzard conceived the idea of creating a park to preserve it for future generations. [92] His vision interested Oscar Roos of Taylors Falls, who deeded a considerable amount of acreage to the state of Minnesota, and State Senator William S. Dedon of Taylors Falls. Other leading citizens from Taylors Falls, St. Croix Falls, St. Paul, and Madison, such as Harry D. Baker, worked together to get Minnesota and Wisconsin to pass the necessary legislation.

The Minnesota Interstate Park was given birth on February 25, 1895, but it would take more time and lobbying to get appropriations needed for land purchases. In March park organizers brought a delegation of Minnesota legislators and more than a hundred "distinguished" guests to the Dalles to see for themselves the value of this scenic wonder. The Taylors Falls Journal followed up on this visit by printing a special pictorial issue extolling the beauty that should be saved. It was sent to both the Minnesota and Wisconsin state legislatures. On April 22, 1895 Minnesota passed the park bill by an overwhelming majority, although without appropriating all of the promised money. [93]

While the Minnesota side had received enthusiastic interest in the nearby state capitol of St. Paul, the Wisconsin legislature in Madison was much more reluctant to commit funds for the venture. "Appropriations for the purchase of the necessary lands within the park limits were very difficult to obtain from Wisconsin legislators," recalled Harry D. Baker, "because so few members of the legislature at that time knew anything about this part of the state." Unlike their neighboring state, Wisconsin had no state parks at that time even though it would later become a leader in conservation. Even when members of the park committee brought photographs of the Dalles to Madison, most legislators still remained disinterested.

George Hazzard, however, was not a man to be put off easily. Even though a Minnesota resident, he lobbied in Madison, often making a complete nuisance of himself. After petitioning and finally haranguing State Senator John M. True of Baraboo for hours, Hazzard received an appropriation to purchase Dalles land. For several years Hazzard and others continued this effort, "getting only perhaps five or ten thousand dollars at each session of the legislature," recalled Harry Baker, "at some sessions nothing at all." Some of the lands also had to be condemned by court action. But by March 1899, the park promoters finally secured the support they needed in Madison and the Wisconsin side of the St. Croix was secured for posterity. Hazzard was appointed commissioner for the Minnesota Park. It is "a monument to the energy and the enthusiasm and foresight not only of George H. Hazzard," declared Baker, "but to those men who had vision enough to see the possibilities of this picturesque and scenic area as the park that it has now become." [94]

Between 1901 and 1911, Harry Baker wrote numerous letters to land owners in the area following whatever scheme or strategy he could to purchase, claim, or condemn land for Interstate Park. As National Park Service lands specialists discovered a half century later, public land acquisition was neither easy nor popular. In a letter dated April 10, 1902 to a local landowner, Baker wrote:

The price you ask is at the rate of $25 per acre, which is over double what we would regard the land as worth. For any agricultural purpose it is certainly not valuable, as the natural meadows, which are a comparatively small proportion of the entire acreage comprise the only part of the land that is fit for anything but pasture. I have consulted with the other members of the commission, and we have decided to offer you $12.50 per acre for the entire tract. I doubt very much if any appraisers appointed in condemnation proceedings would value this land as high. [95]

Baker also authored entries for the Interstate Park in the 1903, 1905, and 1907 editions of the Wisconsin Blue Book. He most likely wrote the eloquent introductory summary for the 1901 edition as well.

Nowhere else are evidences of this power to rend and produce more magnificently portrayed than in the Dalles of the St. Croix, in Polk county, that matchless beauty spot just becoming known as the Inter-State Park, a veritable paradise of Nature's handiwork, owned jointly be Wisconsin and Minnesota, Wisconsin's 600 acres lying east and Minnesota's 300 lying west of the St. Croix river, the villages of St. Croix Falls in Wisconsin and Taylor's Falls in Minnesota situated at the very thresholds of the park. . .State money appropriated for the park is only used for paying for the land and making accessible the natural beauties of the spot. Artificial beautifying is seemed quite unnecessary. [96]

Despite the State of Wisconsin's reluctance to build the park, it eventually committed more resources to the project. Only 292 acres of parklands are in Minnesota, whereas 1734 acres are in Wisconsin "It was by modern values perhaps fortunate," wrote James Taylor Dunn, "that the continued litigation between William Hungerford and Caleb Cushing kept the falls of the St. Croix from being developed as a manufacturing center." [97] As a result, much of the Dalles land was available for the Interstate Park.

The Interstate Park attracted much attention in its first years. In 1898, Warren Manning, a nationally renowned landscape architect and secretary of the American Park and Outdoor Art Association, visited the park. He heartily endorsed the park movement: