|

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE

Forests of Yosemite, Sequoia, and General Grant National Parks |

|

DESCRIPTIONS OF THE TREES.

FIRS.

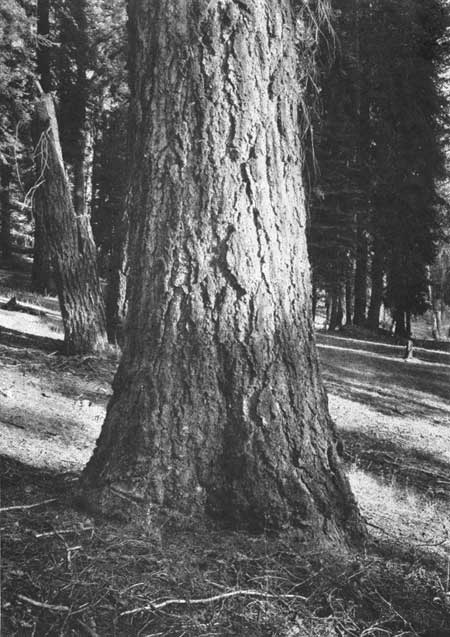

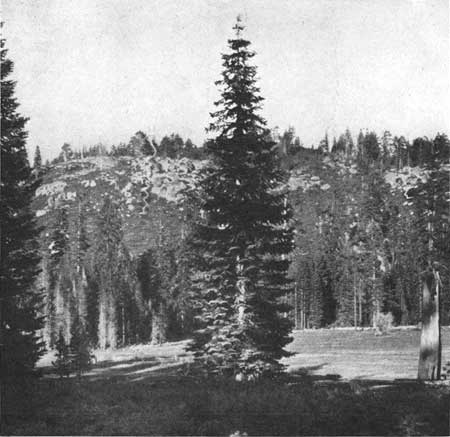

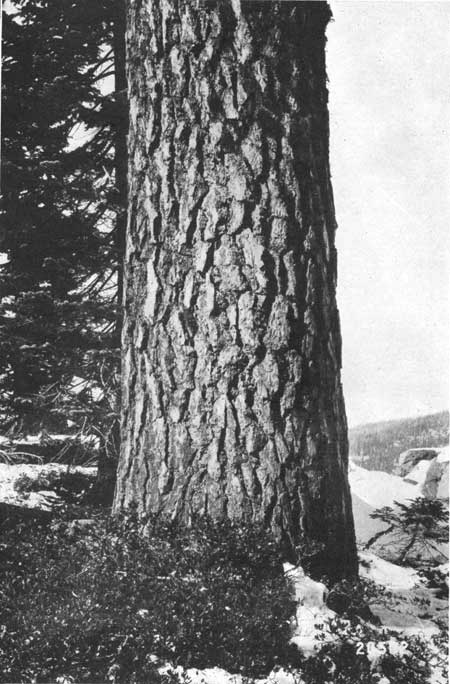

There are two firs in the Sierra region in which the national parks are located, namely, white fir (Abies concolor) and red fir (Abies magnifica). These are among the largest trees of their kind in the world. Mature white firs (fig. 12) are from 4 to 5 feet in diameter, occasional specimens measuring as much as 7 feet. The fir is the tallest tree of the Sierra forests, sometimes attaining a height of 240 feet. The red fir (figs. 13 and 14) is about as tall as the white, but does not usually reach as large diameter. The first, like the spruces, belong to the group of conifers which have short leaves scattered on the twigs instead of clustered as in the pines. In the white fir the leaves are usually 1-1/2 to 2 inches long and stand on opposite sides of the twig in a featherlike arrangement. The leaves of the red fir are shorter, three-fourths to 1 inch long, and generally curl upward. This character is often given as a distinction between the two trees, but it is quite unreliable, for white fir in unfavorable conditions or in old trees produces leaves similar in all these respects to those of the red fir. The only trustworthy leaf distinction is that in the white fir each leaf is slightly channeled lengthwise on the upper surface, while the leaves of the red fir are ridged, or at least convex, on both top and bottom. The appearance of the trunk bark is usually different in the two trees. That of the white fir is ashy gray in color, and the edges of its thin, irregular plates tend to curl up. The bark of the red fir is closely ridged, much like that of the sugar pine, except that it is much darker in color. An unmistakable distinction between the two trees is furnished by the color of interior of the bark, which when chipped into is, in the white fir, a dirty or brownish yellow, while in the red fir bark it is a bright red. The side branches of the red fir are usually shorter than those of the white fir, and, as maturity approaches, its top is rounded off so that it appears dome shaped rather than conical.

|

| FIG. 12.—Trunk of large white fir of average size and form in middle fir belt, where mixed with red fir, diameter 42 inches, height 170 feet. |

|

| FIG. 13.—Red fir (Abies magnifca) 15 inches in diameter and 35 feet high. |

|

| FIG. 14.—Red fir (Abies magnifica). |

The firs seek cool and moist situations, requiring moisture in the air as well as in the ground. The requirements of the red fir are more exacting in these particulars than are those of the white fir. These are the controlling factors in their distribution as given in the discussion of the fir type. The firs can grow in deeper shade than any of their associates in the Sierra forests, and this permits them often to crowd other trees out in the struggle for possession of the soil.

The white fir is a moderately prolific seeder and the red fir is a very prolific one. Heavy seed years occur at intervals of from two to three years, and some seed is borne every year. The cones of the two trees afford another means of distinction between them, those of the white fir being from 3 to 5 inches long, while those of the red fir are from 6 to 8 inches long. The usefulness of this character as a distinction is reduced, however, by the fact that the upright cones of the firs fall to pieces when they discharge their seed, so that the cones can never be found on the ground, unless, to be sure, they have been blighted and thus fall off before they are mature.

These firs grow very rapidly in diameter. The height growth in youth is less rapid than that of the pines, but it continues unabated for a longer period. Under very favorable conditions the white fir may grow to a diameter of 12 inches in 30 years and to 30 inches in 100 years. Ordinarily in this region at 12 inches diameter the trees are about 40 feet high and 50 years old, at 30 inches diameter 150 feet high and 200 years old, and at 60 inches diameter 190 feet high and 450 years old.

The firs are seriously attacked by a fungous disease, so that mature trees are seldom found which are not badly decayed. The fungus often produces unsightly cankers. The trees are also badly attacked by a mistletoe, which kills the tops, and the white fir is badly scarred by fire. The red fir grows at such high elevations that bad fires seldom occur, because of the coolness and moisture.

The wood of the firs is the strongest coniferous timber of the Sierra forests, excepting only that of the Douglas fir, and would make excellent construction timber if it were not so often checked and cracked. This defect and the fact that it warps badly in drying unfit it for use in the better grades of lumber. White fir, however, is sawed to a considerable extent for common lumber. The greatest use of the firs in the future will doubtless be for paper pulp, to which they are excellently adapted, and for which the demand in the United States is fast outstripping the supply of the eastern spruce.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

hill/sec2d.htm

Last Updated: 02-Feb-2007