|

Steamtown

Steam Over Scranton: The Locomotives of Steamtown Special History Study |

|

AMERICAN DIESEL-ELECTRIC LOCOMOTIVES

Dr. Rudolf Diesel filed a patent on an internal combustion engine based on what is called the compression ignition principle in Augsburg, Germany, in 1892. Destined to be known by his last name, the first engine of this type ran on coal, but his second relied on refined oil as fuel. As early as 1893 in a book he wrote, Diesel talked about the applicability of his engine to railroad locomotives. Working with the firm of Klose and Sulzar, Diesel produced the first experimental diesel railroad locomotive in 1909. However, for many years the diesel engine would prove more suitable for use in submarines and for purposes other than powering locomotives.

As it turned out, street railroads or electric streetcar lines provided the key to successful transmission of power from the diesel engine to the drive wheel. Frank Sprague invented the axle-hung direct current motor and the principle of gear drive to the axle as early as 1866 for use on the Manhattan Electrified Railroad in the United States.

As early as 1913, an experimental 60-horsepower diesel-electric railcar appeared in Sweden. About 30 cars of this type, but with more powerful, 150-horsepower engines, soon went into service in Sweden, Denmark, France, and Tunisia.

After experimenting in 1909 with gasoline-electric railcar construction, the General Electric Company sent several of its engineers to Europe in 1911 to investigate continental experiments with diesel electric motive power. The firm then signed a license agreement to use Junkers's opposed-piston engine. General Electric built five experimental diesel-electric switch engines early during World War I, but these failed to have any impact on motive power procurement by the nation's railroads.

General Electric then decided to concentrate on building only the electrical components of such locomotives, leaving the construction of the diesel engine and the body of the locomotive--what the industry referred to as the "carbody"--to other firms. Thus in 1923, General Electric built the electrical components, Ingersoll-Rand the four-stroke diesel engine, and the American Locomotive Company the carbody of a 300-horsepower 60-ton diesel-electric switcher. The builders demonstrated their diesel- electric long and hard on 14 railroads As a consequence, on October 20, 1925, the American Locomotive Company sold the first commercially produced diesel-electric locomotive in the United States to the Central Railroad of New Jersey (also known as the "Jersey Central"), which assigned it the number 1000.

That same year, the Baldwin Locomotive Works formed a team with the De La Vergue diesel engine firm and the Westinghouse Electric Company to build the largest diesel-electric constructed up to that time, a 1,000-horsepower machine powered by a Knudson 12-cylinder two-cycle inverted V-type engine with twin crankshafts geared to a central shaft.

In 1930, General Motors Corporation, principally an automobile manufacturer, acquired the Electro Motive Corporation and the Winton Engine Company, the latter an established producer of diesel engines, and from this merger came a much smaller, much lighter diesel engine capable of producing many horsepower. This advanced diesel engine powered the Chevrolet exhibit at the Chicago World's Fair in 1933. Ralph Budd of the Chicago, Burlington and Quincy Railroad saw it there and decided to use this type of engine for his railroad's Pioneer Zephyr, a prototype of lightweight, stainless steel, streamlined fast passenger trains. On May 26, 1934, the sleek, silver Pioneer Zephyr set off on the return from a trip to Denver to run 1,015.4 miles to Chicago in 13 hours, 4 minutes and 58 seconds, an average speed of 76.61 miles per hour, though in fact the three-car articulated train exceeded 100 miles per hour during the trip. About the same time, the Union Pacific fielded the similar but bright yellow City of Salina, while in 1935 the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe purchased from Electro-Motive Corporation a pair of diesels to power the Super Chief between Chicago and Los Angeles. Thus the 1930s ushered in not only the era of the streamlined "lightweight" passenger train, but the era of diesel- electric motive power for passenger trains as well.

In March 1935, General Motors Corporation began construction of a huge plant for erection of diesel electric locomotives at La Grange, Illinois, where the company would have the capability of building the locomotive carbody on a cast underframe. The locomotives would employ General Electric motors. The first La Grange product proved to be a 600-horsepower diesel-electric switcher with a cab at one end and exposed running boards on each side. It would more or less serve as a model for the most popular switch-engines for more than a decade. In 1937, an enlarged La Grange plant turned out the first E-Units, streamlined passenger locomotives with built-in cab and running boards along each side of the engines concealed in the carbody, a design that came to be called the "covered wagon" type, because cab and engine were totally enclosed. In 1939, Electro-Motive built the first similarly streamlined Model FT freight locomotive, consisting of an "A" unit with cab, and a "B" unit without, coupled together. Two such pair could be operated together as an "A-B-B-A" combination of four locomotives, all relying on a single crew in a single control cab.

That constituted one of the greatest advantages of the diesel-electric locomotive. While a whole book could be written on the invention of multiple-unit control, suffice to note here that a number of diesel electric locomotives could be coupled together, with the controls for each plugged into a single locomotive cab so that a single engineer and fireman could control eight or ten locomotives coupled together on the head of a train. When railroads double-headed or triple-headed steam locomotives, each locomotive required its own engineer and fireman. Thus the diesel-electric locomotive represented a labor-saving, cost-cutting machine. Furthermore, the diesel-electric did not need the large quantities of water that steam locomotives required, and thus did not require the maintenance of expensive water tanks, pipelines, and water cranes at intermittent points along its lines, which meant another saving in cost.

The diesel-electric locomotive was not the only type of diesel locomotive. A number of firms such as H.K. Porter made small switch engines that were diesel-mechanicals, without electric generators and motors but using chain or geared drives. Later, two railroads would experiment with Krauss-Maffei German-built diesel-hydraulic locomotives. But the diesel-electric locomotive proved so overwhelmingly successful that the mere term "diesel" as applied to a railroad locomotive has come to mean almost automatically a diesel-electric.

At the beginning of the diesel locomotive era, railroaders simply applied the Whyte system of locomotive classification used for steam locomotives, but eventually a different system for electric and for diesel-electric locomotives evolved in which the letter "A" applied to a single powered axle with two wheels, the letter "B" to a truck with two powered axles and four wheels, the letter "C" to a truck with three power axles and six wheels, and so on. The same classification applied to electric locomotives, some of which had unpowered axles to which the old Whyte system numbers could be applied. But a small switch engine like the prototype developed by Electro-Motive that featured two four-wheel trucks with all four axles powered would fall into the classification of "B-B" type in this new system, while a passenger diesel-electric with two six-wheel powered trucks, each with three axles, would be a ""C-C" type. It must be kept in mind that this constitutes an entirely different use of the letters than does referring to a "covered wagon" type diesel-electric locomotive with cab as an "A" unit or a similar locomotive without cab as a "B" unit.

Thus by 1940, the streamlined E-type passenger and FT-type freight diesel-electric locomotives and the typical "SW" yard switcher which were to dominate the diesel market for many years had been introduced. Additionally, in 1941 Alco and General Electric had introduced a new type of locomotive with a 1,000-horsepower engine and an offset cab, with exposed running boards, which it called an RS type or "road switcher," capable of carrying out multiple duties. This, along with the products of the Electro-Motive Division of General Motors, would be a prototype of much yet to come.

It is not the purpose of this discussion to provide a complete history of the development and use of the diesel-electric locomotive, which indeed would require many volumes; but in providing an overall context for those in the Steamtown collection, it is necessary to point out that other manufacturers existed. Fairbanks-Morse, a mid-19th century firm that built scales, then railroad track scales, then other railroad equipment, and after 1900 gasoline engines and eventually electric motors, developed in the early 1930s a very successful opposed-piston diesel engine for use in navy submarines. Eventually the company began experimenting with this engine in a railroad locomotive, particularly in a switcher used on the Reading in 1939 and in railcars used on the Southern Railway.

Then World War II intervened, and the U.S. government through the War Production Board began assigning priorities for manufacturing and for allocation of raw materials to companies. The government allowed construction of no more diesel-electric locomotives for passenger traffic, restricting diesel-electric locomotive production to yard switchers and freight locomotives. Moreover, restrictions imposed on particular companies affected their destiny beyond the war. Fairbanks, Morse & Company had produced a diesel engine that proved to be so efficient, the War Production Board diverted its entire output for use in navy submarines, thus forcing Fairbanks-Morse entirely out of the diesel- electric locomotive business until 1944, during a critical period in the development of diesel-electric locomotives. Baldwin Locomotive Works, as the nation's foremost builder of steam locomotives, received War Production Board encouragement in that field, and could market its existing line of diesel-electric yard switchers, but the War Production Board would not allow it to undertake design and development of diesel-electric freight and passenger units. As a consequence, Baldwin could enter the diesel-electric field in a serious way only after 1945, by which time the Electro-Motive Division of General Motors Corporation and the American Locomotive Company had a near-stranglehold on the market for freight and passenger diesels. Both Baldwin (soon to merge with Lima-Hamilton) and Fairbanks-Morse produced notable diesel-electric locomotives after World War II, some of which still operated in 1990, but neither got a sufficient grip on the market to make a success of diesel sales.

The Lima-Hamilton Corporation, another firm that entered the diesel-electric production market, represented the 1947 merger of the Lima Locomotive Works and the General Machinery Corporation (the name Hamilton coming from an earlier General Machinery component, the Hamilton Press and Machinery Company). The new firm produced its first diesel-electric locomotive that same year. However, only three years later, on November 31, 1950, the Lima-Hamilton Corporation merged with the Baldwin Locomotive Works to form the Baldwin-Lima-Hamilton Corporation.

In the years that followed, passenger traffic declined on American railroads until the federally chartered National Railroad Passenger Corporation, marketed under the name of "Amtrak," short for American Track, took over most passenger service on America's railroads. With the decline in passenger traffic came a decline in the use of covered wagon-type diesels for passenger and even for freight service. The road switcher-type of locomotive eclipsed even the streamlined freight locomotive, and diesel-electric locomotives became uniformly uglier and more utilitarian in design. The handsome EMD E and FT units began to vanish, as did the Alco equivalents, for the PA and FA had begun to disappear even earlier.

Throughout this period the diesel-electric locomotive had been eclipsing the steam locomotive in the United States. The American Locomotive Company built its last steam locomotive in 1948, the Lima Locomotive Works erected its last in 1949, and Baldwin soon followed. Dieselization of the first major American railroad occurred in 1949, and extended to other railroad companies throughout the 1950s. Insofar as regular service was involved, and excepting special cases such as short lines that emphasized steam passenger excursions, narrow gauge lines, or other special cases, America's railroads were essentially dieselized by 1960, and the steam locomotive had nearly vanished from the railroads of the nation.

As its name implies, the Steamtown Foundation did not intend to acquire diesel-electric locomotives for museum purposes. When the foundation moved to Scranton, Pennsylvania, in 1984, it needed diesel-electric motive power as a supplement, and occasionally as a substitute, for steam motive power, and accordingly leased Delaware & Hudson Locomotive No. 4075. The deal included an option to purchase, and lease payments could be applied to purchase; consequently, when lease payments approached the cost of purchase and it seemed likely that the foundation would need the locomotive for quite some time, it proved cheaper to buy it outright than to continue to lease it, so the foundation did just that. Subsequently the Norfolk & Western Railway, which had merged with the old Nickel Plate (New York, Chicago & St. Louis) and the Wabash, provided a Wabash switcher and a Nickel Plate "General Purpose" locomotive or "GEEP." Still later the foundation acquired Milwaukee Road and Kansas City Southern F7 covered wagon units.

Because the purpose of Steamtown National Historic Site is the preservation of equipment and rolling stock related to the era of steam railroading, none of the diesel-electric locomotives is considered suitable as a museum locomotive, although some of them are old enough to be considered historic. Steamtown National Historic Site has, however, found it prudent to keep one or more of these diesels as serviceable switch engines for use around the yard and for emergency service out on the excursion line in case of the breakdown of a steam locomotive while in use.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Addie, A.N. "The History of the Diesel-Electric Locomotive in the United States," Chapter 4 in Railway Mechanical Engineering: A Century of Progress , Car and Locomotive Design. New York: The American Society of Mechanical Engineers, Trail Transportation Division, 1979: 103-136.

Albert, Dave, and George F. Melvin. New England Diesels. Omaha: George R. Cockle and Associates, 1975.

Diesel Locomotive Rosters: The Railroad Magazine Series. New York: Wayner Publications, n.d.

Dolzall, Gary W., and Stephen F. Dolzall. Diesels from Eddystone: The Story of Baldwin Diesel Locomotives. Milwaukee: Kalmbach Books, 1984.

Dover, Don. "All About F's." Extra 2200 South: The Locomotive Newsmagazine, Vol. 8, No. 2 (Jan. 1970): 19-21.

__________. "All About SW's." Extra 2200 South: The Locomotive Newsmagazine, Vol. 9, No. 12 (July-Aug. 1973): 20-25.

Duke, Donald, and Keilty, Edmund. RDC: The Budd Rail Diesel Car. San Marino: Golden West Books, 1990.

Early Diesel-Electric and Electric Locomotives. Omaha: Rail Heritage Publications, 1983.

Extra 2200 South: The Locomotive Newsmagazine. [The entire run of this periodical is devoted nearly 100 percent to diesel locomotives and their history, and keeping up with current day use, status, and location.]

Foell, Charles F., and M.E. Thompson. Diesel-Electric Locomotive. New York: Diesel Publications,Inc., 1946.

Keilty, Edmund. Interurbans Without Wires. Glendale: Interurban Press, 1978.

__________. Doodlebug Country. Glendale: Interurban Press, 1982.

__________. The Short Line Doodlebug. Glendale: Interurban Press, 1988.

Kerr, James W. General Motors Advanced Generation Diesel-Electric and Electric Locomotives: The Second and Third Generation Locomotives. Alburg: DPL-LTA, 1987.

Kirland, John F. Dawn of the Diesel Age: The History of the Diesel Locomotive in America. Glendale: Interurban Press, 1983.

__________. The Diesel Builders: Fairbanks-Morse and Lima-Hamilton. Glendale: Interurban Press, 1985.

_________. The Diesel Builders: American Locomotive Company and Montreal Locomotive Works. Glendale: Interurban Press, 1989.Loco 1, The Diesel: A Survey of Internal Combustion Locomotives from 1901 through 1966. Ramsey: Model Craftsman Publishing Corp., 1966.

Maywald, Henry. E Units: The Standard Bearer of America's Passenger Trains. Hicksville: N.J. International, 1988.

Mulhearn, Daniel J., and Taibi, John R. General Motors' F Units: The Locomotive that Revolutionized Railroading. New York: Quadrant Press, 1982.

Olmsted, Robert P. The Diesel Years. San Marino: Golden West Books, 1975.

Parker, C.W. "The Development of Remote Multiple-Unit Locomotive Control," Chapter 6 in Railway Mechanical Engineering: A Century of Progress, Car and Locomotive Design. New York: The American Society of Mechanical Engineers, Rail Transportation Division, 1979: 161-170.

Smith, Vernon L. "The Diesel from D to L - 1," Trains, Vol. 39, No. 6 (Apr. 1979): 23-29.

__________. "The Diesel from D to L - 2," Trains, Vol. 39, No. 7 (May 1979): 44-51.

__________. "The Diesel from D to L - 3," Trains, Vol. 39, No. 8 (June 1979): 46-51.

"The Diesel from D to L - 4," Trains, Vol. 39, No. 9 (July 1979): 44-49.

Extensive literature on the diesel-electric locomotives treated railroad by railroad exists. A trend in recent years with respect to certain large railroad systems such as the Burlington Northern, the Southern Pacific, and the Union Pacific has been publication of an "annual' monograph documenting in rosters, photographs and captions, and some text or narrative the history during the previous year of diesel motive power on particular systems.

CHICAGO, MILWAUKEE, ST.PAUL & PACIFIC MARYLAND MIDLAND RAILWAY NOS. 97A, 97C

Owner(s):

Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul & Pacific

Maryland Midland Railway

Road Number(s): 97A, 97C

Whyte System Type: 0-4-4-0

Type: B-B

Class: FP7

A.A.R.Builder: Electro-Motive Division, General Motors Corporation, La Grange, Ill.

Date Built: 1950

Builder's Number:

Cylinders (diameter x stroke in inches): 8-1/2 x 10

Boiler Pressure (in lbs. per square inch): Not applicable

Diameter of Drive Wheels (in inches): 40

Tractive Effort (in lbs.): 40,000

Tender Capacity:

Coal (in tons): Not applicable

Oil (in gallons): 1,200

Water (in gallons): Not applicable

Weight on Drivers (in lbs.):

Remarks: This 1,500-horsepower freight and passenger locomotive has a 16-cylinder, two-cycle "V" form engine.

Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul and Pacific Railway FP7 Nos. 97A and 97C

History: The "Milwaukee Road," more properly the Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul and Pacific Railway Company, gained fame in the 20th century for its Hiawatha passenger trains, named for the Indian heroine of Longfellow's poem, and for electrified trackage over the Continental Divide at Pipestone Pass, Montana, as well as for the company's nearly unique "Little Joe" electric locomotives, a type supposedly nicknamed for Joseph Stalin because they were designed and built for export to the Soviet Union for use on the Trans-Siberian Railway; however, as a result of the development of the Cold War, they were embargoed by President Harry S. Truman, and diverted instead in 1948 to sale to two American railroads, the Milwaukee Road and the Chicago, South Shore & South Bend.

The old Milwaukee & St. Paul Railway, incorporated in Wisconsin on May 5, 1863, grew and extended its trackage, consolidated with other lines, and changed its name on February 11, 1874, to Chicago, Milwaukee & St. Paul Railway to reflect its growth and expanded ambitions. As customarily occurred in railroad history, the company purchased many smaller lines and absorbed them into its system, thereby reaching Kansas City, Missouri; Omaha, Nebraska; and points in Iowa, Minnesota, and North and South Dakota. Ambition continued to grow also, so that the original company sponsored a subsidiary, the Chicago, Milwaukee and Puget Sound Railway, which undertook construction of a 2,081-mile extension from Mobridge, South Dakota, across the plains and through five mountain ranges in Montana, Idaho, and Washington to reach Seattle, on Puget Sound. But the Milwaukee Road, to use its nickname, was the last of the three northern transcontinentals to be completed, on May 14, 1909, and it faced competition with the already well-established Northern Pacific Railway, which had completed a through line to the Pacific Coast on September 8, 1883, and the Great Northern Railway, which drove its final spike on January 6, 1893. On March 31, 1927, the two railroads, the Chicago, Milwaukee & St. Paul and the Chicago, Milwaukee & Puget Sound, consolidated and reincorporated as the Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul and Pacific Railway.

The trials and tribulations, rise and fall of its fortunes, and the long decline of the Milwaukee Road is a story documented elsewhere, as is the story of its partial electrification and ultimate replacement of its remaining steam locomotives with diesel-electrics. For this account it is sufficient to note that by the 1950s the Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul and Pacific was in the middle of a program of replacing its remaining steam motive power with diesels, and it was in this context that the company ordered from the Electro-Motive Division of General Motors Corporation at La Grange, Illinois, 16 sets of three diesel-electric FP7 combinations, each consisting of an "A" unit with cab, a "B" unit without cab, and another "A" unit with cab. The Milwaukee Road numbered them as 16 three-unit sets in the series 90 through 105, designating the individual units within each set with the letters "A," "B," and "C" (which is an entirely separate use of those letters from the aforementioned designating of cab units as "A" units and cabless units as "B" units). Thus, for each of the numbers 90 through 105 there was an "A," "B," and "C," such as No. 97A, 97B, and 97C. It was possible to work these together in different combinations, such as an A-B-B-A or an A-B-B-B-A or, on the other hand, an A-A, such as coupling 97A and 97C back to back without 97B. Apparently the railroad found it desirable almost immediately to employ these locomotives in two- rather then three-unit sets. The "FP" in their model designation meant "Freight/Passenger," and indeed these units appeared in trains of both types. Electro-Motive delivered these 48 units in 1950 and 1951, probably painted orange and maroon, the road's passenger colors, but in 1959 the company renumbered the 15 units in the 90 through 94 sequence to 60 through 64, painted them orange, and assigned them exclusively to freight service. The remainder continued in passenger service, and No. 97C is known to have operated in Chicago area suburban service, but eventually even the 95 through 105 series locomotives hauled their share of freight trains. These versatile and handsome covered wagon units, so named because their body enclosed not merely the cab but also the running boards alongside the diesel engines, hauled many a freight and passenger train over Milwaukee Road rails.

As mentioned earlier, the Milwaukee Road was the third and last of the three northern "transcontinentals" to be completed, and by the 1970s it was failing to compete successfully with the Burlington Northern. By 1980, the western portion of the line, across Montana, Idaho, and Washington, had collapsed financially, and all that would survive--for a while--were midwestern portions of the company. Thus, it was to have much surplus motive power for sale, including diesel-electric locomotives Nos. 97A and 97C; what happened to cabless No. 97B is unclear.

These two locomotives, and possibly others, came into the ownership of a group of investors who styled themselves FP7 Associates." Early in 1984, this firm leased diesel-electric locomotives Nos. 97A and 97C to the Maryland Midland Railway. The Maryland Midland immediately sent the two units to the Winchester & Western Railway at Gore, Virginia, for overhaul and restoration to service. Work proceeded slowly, and neither unit was ready for operation on excursion runs in the fall of 1984. Locomotive No. 97A, in fact, moved back to the Maryland Midland, arriving there on May 6, 1985, with no work having been done on it. Its body, according to one report, was in "deplorable" condition, and although the Maryland Midland shop force fired up its diesel engine, the locomotive was a long way from being serviceable for handling regular traffic.

Meanwhile, the Winchester & Western did restore Locomotive No. 97C to operating condition, and painted it black with the letters "WINCHESTER & WESTERN" in yellow on its sides. It moved sand trains and, on May 11 and 12, 1985, a couple of excursion trains. Subsequently the Winchester & Western sent the engine back to the Maryland Midland where it arrived on June 4, 1985. The latter company immediately pressed the locomotive into freight service, as several of its other diesels had broken down. Late in July, however, the No. 97C entered the Maryland Midland shop where the company had it relettered "WESTERN MARYLAND" in a slanted style known as "speed lettering," with "WM" on its nose. Of course, historically, the engine never had belonged to the historic Western Maryland Railway Company.

That same month the Maryland Midland obtained through Gibbs Railway Equipment of Neptune Beach, Florida, three former Norfolk & Western GP9 (General Purpose) diesel-electric locomotives. Within two years, in 1987, the Steamtown Foundation had acquired units 97A and 97C and moved them to Scranton, Pennsylvania. The Steamtown Foundation shopped Locomotive No. 97C to repaint it in a maroon and gray color scheme, letter it "LACKAWANNA," and assign it the new number 637. Then the locomotive went into service on passenger excursions to Pocono Summit during the summer of 1987.

Condition: Locomotive No. 97C is in essentially operable condition, and, of course, has been recently repainted. Locomotive No. 97A has been used as a source of replacement parts for No. 97C, so is inoperable, though of course, with enough work, it, too, could be restored to operable condition. Meanwhile, for foreseeable future, it is being cannibalized for parts to keep sister unit 97C operational. The body on No. 97A was regarded as being in very poor condition when the Maryland Midland received the unit, and that condition is not believed to have been corrected.

Recommendation: Locomotive No. 97C is recommended for emergency uses and possibly for helper service on excursion trains, though not for museum purposes. However, it must be recognized that this particular type of locomotive, though only 36 years old in 1988, is becoming increasingly scarce and historic, and that it is a type of locomotive acquired by many railroads for freight and passenger service to replace steam locomotives.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Derleth, August. The Milwaukee Road: Its First 100 Years. New York: Creative Age Press, 1948.

Dorin, Patrick C. The Milwaukee Road East. Seattle: Superior Publishing Company, 1978.

Hyde, Frederick W. The Milwaukee Road. Denver: Hyrail Productions, 1990. [On p. 19 is a color photo of No. 97A at night in Savanna, Illinois, on May 27, 1979, and on p. 23 is a color photo of No. 97A on freight train No. 106 at Green Island, Iowa.]

Meeker, Ken. "The Milwaukee Road West at Closing Time." Pacific News, Vol. 19, No. 10 (Oct. 1979): 6-13.

Meise, John. "It's the Maryland Midland." Railfan & Railroad, Vol. 5, No. 13 (Nov. 1985): 50-56.

Mulhearn, Daniel J., and Taibi, John R. General Motors' F Units: The Locomotives that Revolutionized Railroading. New York: Quadrant Press, 1982.

Moody's Transportation Manual, 1962. New York: Moody's Investors' Service, Inc., 1962: 82-99.

Olmsted, Robert P. Milwaukee Rails. Woodbridge: McMillan Publications, 1980.

Scribbins, Jim. The Hiawatha Story. Milwaukee: Kalmbach Publishing Company, 1970. See especially roster and p. 255.

Steinheimer, Richard. The Electric Way Across the Mountains. Tiburon: Carbarn Press, 1980.

Wood, Charles R., and Dorothy M. Wood. Milwaukee Road West. Seattle: Superior Publishing Company, 1972.

KANSAS CITY SOUTHERN RAILWAY NO. 4061

Owner(s):

Kansas City Southern Railway

Road Number(s): 74D

Renumbered: 91

Renumbered: 4061

Whyte System Type: 0-4-4-0

A.A.R. Type: B-B

Class: F7Am

Builder: Electro-Motive Division, General Motors Corporation, La Grange, Ill.

Date Built: February 1951

Builder's Number: 9164

Cylinders (diameter x stroke in inches): 8-1/2 x 10

Boiler Pressure (in lbs. per square inch): Not applicable

Diameter of Drive Wheels (in inches): 40

Tractive Effort (in lbs.): 52,400

Tender Capacity:

Coal (in tons): Not applicable

Oil (in gallons): 1,200

Water (in gallons): Not applicable

Weight on Drivers (in lbs.): 230,000

Remarks: This F7 freight locomotive featured a 16-cylinder, two-cycle "V"-form engine, Model 567B, that provided 1,500 horsepower. Rebuilt to an F7Am.

Kansas City Southern Railway F7a Locomotive No. 4061

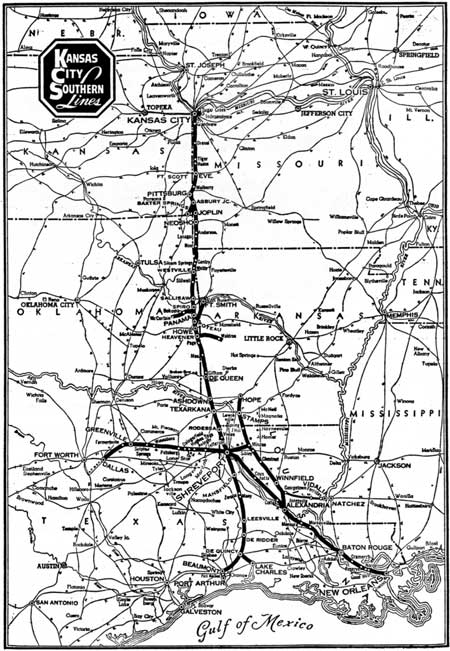

History: The Kansas City Southern (KCS) Railway ran exactly where its corporate name said it would: from Kansas City, Missouri, 788.91 miles southward to the Gulf of Mexico at Port Arthur, Texas. En route, the railway crossed Missouri, Kansas, Oklahoma, Arkansas, Louisiana, and Texas, with stations at Pittsburg, Kansas; Joplin, Missouri; Fort Smith, Arkansas; and Shreveport, Louisiana, as well as many other points between. Other lines of the KCS provided service to Dallas, Texas, and Baton Rouge and New Orleans, Louisiana, with the result that by 1962 the entire KCS system operated 957.69 miles of main line track.

Incorporated on March 19, 1900, the Kansas City Southern Railway succeeded the Kansas City, Piusburg and Gulf Railway, whose property had come up for sale under foreclosure. Lines in Texas operated by the Texarkana and Fort Smith Railway continued under that name to satisfy Texas law until December 31, 1943, when the Kansas City Southern, through the intervention of the Interstate Commerce Commission and the United States Supreme Court, was able to dissolve and absorb the Texas company. Similarly, with only ICC permission, the Kansas City Southern was able to absorb in 1935 the Kansas City, Shreveport and Gulf Railway.

The Kansas City Southern provided a Gulf outlet for agricultural products of the middle Missouri River Valley. Large tracts of pine timberlands, which also included some hardwoods, lay adjacent to the line, and it served important oilfields and refineries as well as coalfields along the Kansas-Missouri and Missouri-Arkansas borders, in addition to other industries.

The Kansas City Southern completed conversion from steam to diesel-electric motive power in 1953, earlier than many other lines. By the end of 1961 the company operated 48 diesel-electric freight locomotives, 14 passenger, 11 multiple purpose, and 37 switchers, not to mention 4,828 freight cars, 66 passenger cars, and 133 maintenance-of-way cars.

Among the freight locomotives, in February 1951 the Kansas City Southern had taken delivery from the Electro-Motive Division of General Motors Corporation of two F7a covered wagon or streamlined freight locomotives, part of a larger order of 14 F7a and F7b locomotives bought between October 1949 and April 1951, including No. 74d. Later, the Kansas City Southern renumbered this unit 91, and still later gave it the number 4061. Its operational history is yet unknown, but it undoubtedly moved freight trains over a substantial part of the system for many years.

In April 1987, the Kansas City Southern reportedly sold No. 4061 to Canada's version of Amtrak, VIA Rail Canada, known more familiarly simply as "VIA." What happened then remains unclear, but within nine months the Steamtown Foundation had acquired the locomotive in Scranton, Pennsylvania.

Condition: Painted Kansas City Southern white but with the red KCS initials blocked out on each side, this 1,500-horsepower locomotive reportedly needs an entirely new diesel engine. It has not operated since received at Steamtown.

Recommendation: Representing the era of most attractive, streamlined "covered wagon" type dieselelectric locomotives, this Kansas City Southern engine may be used as an early example of a diesel locomotive.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Frailey, Fred W. "The Kansas City Southern Story 1--The Railroad That Unraveled." Trains, Vol. 39, No. 10 (Aug. 1979): 22-29.

________. "The Kansas City Southern Story 2--President Carter (Tom, that is) Puts a Railroad Back Together." Trains, Vol. 39, No. 11 (Sept. 1979): 22-32.

Lynch, Terry, and W.D. Caileff, Jr. Kansas City Southern: Route of the Southern Belle. Boulder Pruett Publishing Company, 1987: 209-210.

Moody's Transportation Manual, 1962. New York: Moody's Investors' Service, Inc., 1962: 1058-1071.

Mulhearn, Daniel J., and Taibi, John R. General Motors' F Units: The Locomotives That Revolutionized Railroading. New York: Quadrant Press, 1982.

NEW YORK, CHICAGO AND ST. LOUIS RAILROAD NO. 514

Owner(s):

New York, Chicago & St. Louis Railroad 514

Norfolk and Western Railway 2514

Whyte System Type: 0-4-4-0

A.A.R. Type: B-B

Class: ERS-17E Model GP9

Builder: Electro-Motive Division, General Motors Corporation, La Grange, Ill.

Date Built: 1958

Builder's Number: 24505

Cylinders (diameter x stroke in inches): 8-1/2 x 10

Boiler Pressure (in lbs. per square inch): Not applicable

Diameter of Drive Wheels (in inches): 40

Tractive Effort (in lbs.):

Horsepower: 1,750

Tender Capacity:

Coal (in tons): Not applicable

Oil (in gallons): 1,800

Water (in gallons):

Weight on Drivers (in lbs.):

Remarks:

New York, Chicago and St. Louis Railroad GP-9 Diesel-Electric Locomotive No. 514

History: The Norfolk Southern Corporation came to life in March 1982 with Interstate Commerce Commission approval to merge the Norfolk and Western Railway and the Southern Railway into one mostly end-to-end system, blanketing the southeastern United States from New Orleans, Louisiana; Mobile, Alabama; and Palatka, Florida, north to Washington, D.C., and to Memphis, Tennessee (principally the territory of the old Southern Railway), and from Norfolk, Virginia, westward through West Virginia to Cincinnati, Ohio, and as far as East St. Louis, Illinois (largely the territory of the old Norfolk and Western Railway).

Meanwhile, the transportation museum at Roanoke, Virginia, had obtained on loan from the Steamtown Foundation in Vermont for temporary exhibit the "A" Class former Norfolk and Western 2-6-6-4 articulated Locomotive No. 1218. Over a period of years that museum came to regard the locomotive as its property, not a loan, and the Norfolk and Western (N&W) eventually got into the matter when it desired to overhaul the locomotive for operation for publicity purposes, railfan excursions, and other special events. While the Steamtown Foundation apparently had a clear title to the locomotive and the Roanoke museum did not, the N&W put further pressure on the Steamtown group by indicating it would never allow the locomotive to move over its rails out of Roanoke, effectively the only way Steamtown could get it back. Since Steamtown had no answer to this stand, and was by then in the process of moving to Scranton, Pennsylvania, the Steamtown Board decided to accept two diesel- electric locomotives from the Norfolk and Western, which by then had come under the corporate umbrella of the Norfolk Southern, in exchange for giving the Norfolk Southern clear title to No. 1218.

Before creation of the Norfolk Southern, the Norfolk and Western had recently merged with the old Nickel Plate Road, known by the corporate name of New York, Chicago and St. Louis Railroad, and with the Wabash Railroad, acquiring from those firms not only their track but all their locomotives, which left the consolidated Norfolk and Western and eventually the Norfolk Southern with surplus and somewhat out-of-date motive power. Thus it proved no problem for the Norfolk Southern to come up with a Nickel Plate GP-9, No. 514, and a former Wabash SW-8 switcher to offer in exchange for No. 1218, a small price to pay for so valuable and rare a steam locomotive.

The Norfolk and Western GP-9 locomotive that the Norfolk Southern traded to Steamtown (the SW-8 is treated in a later section of this study under the heading Wabash Railroad) had been built in 1958 for the New York, Chicago and St. Louis Railroad, but carried the lettering, as had long been the custom even in the days of steam locomotives, of that railroad's nickname: "Nickel Plate Road." A general purpose B-B type diesel-electric, equivalent to a road switcher, it had been built by the Electro Motive Division of the General Motors Corporation at La Grange, Illinois. The locomotive was the fifth in the ERS-17e class of 20 locomotives numbered 510 through 529. Weighing 245,800 pounds, the locomotive put out a tractive effort of 61,450 pounds.

The operational history of this locomotive has not been researched, but as Jim Boyd and M.C. McIlwain observed in their 1967 article on the line, the Nickel Plate Road "was a bridge-route freight hauler in the most competitive market in the country." Between the Illinois traffic "gateways," or connections with other railroad systems, and Buffalo, New York, the Nickel Plate had the reputation of providing fast service. During the 1950s its classic fast Berkshire steam locomotives regularly outran the diesel-electric locomotives of its competitors, especially the New York Central, the Erie and the Wabash, a situation that created little enthusiasm for early conversion to diesel-electric locomotives. Consequently, although the New York, Chicago and St. Louis bought diesel-electric yard switchers as early as 1940, it bought no road units until the 1950s. This relatively late acquisition of main line diesel-electric motive power spared the Nickel Plate the era of diesel experimentation in the 1940s that, as Boyd and McIlwain pointed out, "cluttered the rosters of most other roads" with oddball, experimental, and less-than-satisfactory locomotives. When finally it bought diesel-electric locomotives, completing dieselization of its motive power roster in 1958, the Nickel Plate invested conservatively in Alco PAs for passenger trains and hood units for all freight service: Alco or EMD B-B types (with two pair of four-wheel trucks each) for main line traffic and secondary line freight hauls, and C-C units from the same builders (featuring two six-wheel power trucks each) for use in the coal fields of southern Ohio. No. 514 counted among the B-B units used on main lines and secondary freight lines.

In 1966, the old New York, Chicago and St. Louis, the famed Nickel Plate Road, lost its identity through merger into the Norfolk & Western Railway. At the same time, the N&W swallowed the Nickel Plate's old adversary, the Wabash Railroad, creating a system under the N&W name that stretched from Norfolk, Virginia, and Hagerstown, Maryland, to Buffalo, New York; Chicago, Illinois; and St. Louis, Missouri (or to be absolutely precise, across the river from it to East St. Louis, Illinois), including most of the territory between such points.

The Norfolk and Western Railroad had been organized on January 15, 1896, under the laws of the Commonwealth of Virginia to succeed the old Norfolk and Western Railroad, which it did on September 24, 1896. That company had been incorporated on May 3, 1881, to take over the Atlantic, Mississippi and Ohio River Railroad, which had defaulted on payment on bonds. The latter company had come into existence on November 12, 1870, as a consolidation of the Norfolk & Petersburg Railroad, chartered on March 15, 1851 and opened for business in 1852; the South Side Railroad, chartered in 1846 and opened for business in 1854; and the Virginia & Tennessee, chartered in 1849 and opened for business in 1857. So the Norfolk and Western's antecedents predated the Civil War.

The Norfolk and Western, on merging with the Nickel Plate and the Wabash, renumbered the motive power of the three roads into a compatible system, which required renumbering the 510 series Nickel Plate diesels into the 2510 through 2529 series, wherein No. 514 became No. 2514. A second renumbering by the Norfolk and Western did not affect this particular locomotive, which remained No. 2514. After coming under the Norfolk Southern umbrella, the Norfolk and Western retired No. 2514 on April 5, 1985, and gave it to the Steamtown Foundation in Scranton, Pennsylvania, which promptly repainted it to Nickel Plate colors and lettering, still later repainting and relettering it fictionally as a Lackawanna locomotive so it would be compatible with the steam locomotive and passenger cars used on the excursions out of Scranton to Elmhurst and later Moscow and Pocono Summit.

Condition: This locomotive is basically operational.

Recommendation: No. 514 is used by Steamtown NHS as its basic shop and yard switcher, since it is far easier to maintain and operate for these limited operations than any steam locomotive in the collection. It should be repainted and relettered in a historically accurate Nickel Plate Road color scheme.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Boyd, Jim, and M. Chadwick McIlwain. "Nickel Plate Road," Railroad Model Craftsman, Vol. 36, No. 6 (Nov. 1967): 26-33.

Dover, Dan. "Nickel Plate Road (New York, Chicago & St. Louis), A Final Roster," Extra 2200 South, The Locomotive Newsmagazine, Vol. 13, No. 10 (April-May-June 1968): 30.

Jane's World Railways, 1986-87. New York: Jane's Publishing, Inc., n.d.: 814-815. [Norfolk Southern information.]

Moody's Transportation Manual, 1962. New York: Moody's Investors' Service, Inc., 1962: 65-82, 841-857, 1135-1155, 1405.

Rehor, John A. The Nickel Plate Story. Milwaukee: Kalmbach Publishing Company, 1965. [See especially p. 417.]

Reich, Sy. "Final Roster of the Nickel Plate Road." Railroad, Vol. 102, No. 3 (July 1977): 52-53.

WABASH RAILROAD NO. 132

Owner(s):

Wabash Railroad 132

Norfolk and Western Railway 3132

Whyte System Type: 0-4-4-0

A.A.R. Type: B-B

Class: D-8 Model SW-8

Builder: Electro-Motive Division, General Motors Corporation, La Grange, Ill.

Date Built: February 1953

Builder's Number: 17593

Cylinders (diameter x stroke in inches): 8-1/2 x 10 (eight)

Boiler Pressure (in lbs. per square inch): Not applicable

Diameter of Drive Wheels (in inches): 40

Tractive Effort (in lbs.): Horsepower: 800

Tender Capacity:

Coal (in tons): Not applicable

Oil (in gallons): 600

Water (in gallons):

Weight on Drivers (in lbs.): 232,100

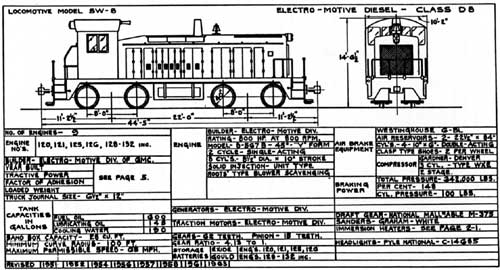

Remarks: This SW-8, 800-horsepower diesel-electric locomotive featured a Model 8-567B 45 degree "V"-form engine.

Wabash Railroad SW-8 B-B Switching Locomotive No. 132

History: The Wabash Railroad after World War II consisted of an Ohio company incorporated September 2, 1937, to reorganize a bankrupt Wabash Railway; on March 15, 1941, it completed a reorganization plan for the purpose, and soon the booming World War II traffic helped the company back to solvency.

The oldest antecedent of the Wabash was the Northern Cross Railroad, chartered about 1837 to run from Quincy, Ohio, to the Indiana state line. This grew into the Toledo, Wabash & Western Railway, whose 678 miles of track its management reorganized in 1877 as the Wabash Railway Company. Two years later it merged with the St. Louis, Kansas City & Northern Railway that added 778 miles west of the Mississippi to the new firm, now named the Wabash, St. Louis & Pacific Railway. By 1889, the railroad had grown to about 3,518 miles of track, at which time it reorganized yet again, this time emerging as the Wabash Railroad Company.

Bankruptcy of this company about 1915 resulted in sale under foreclosure on July 21 of that year and its reorganization on October 22, 1915, as the Wabash Railway Company. It was this company that went into bankruptcy during the Depression.

After World War II, the Wabash Railroad Company commenced, in 1949, its program of fully replacing steam with diesel-electric locomotives. At that time it owned two diesel passenger locomotives and 40 diesel switchers. The Wabash retired its last steam locomotive from service on August 11, 1955, completing conversion to diesel motive power. By December 31, 1961, the company had 322 diesel units, including 22 passenger, 141 freight, 53 road switchers, and 106 switchers, representing an investment of $47,000,000. At that time the railroad operated in Michigan, Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Missouri, and Iowa a total of 1,995.11 miles of main line, with trackage rights over 424 more. The east-west main line extended from Buffalo, New York, westward north of Lake Erie to St. Louis and Kansas City, Missouri, with other main lines to Chicago, Toledo, Des Moines, and Omaha. By 1961 a Pennsylvania Railroad subsidiary owned a controlling 62 percent of Wabash stock.

Among the 106 diesel switchers the Wabash had acquired, nine were EMD Model SW-8 800- horsepower diesel-electrics that the Wabash classed as D-6 type. Numbered among the series 120 through 132, along with some locomotives from another builder, the first two of these came out of the Electro-Motive Division Shop in October 1950, two in September 1951, and the last five in February 1953. One of the last group, possibly No. 132, photographed in St. Louis, Missouri, on November 27, 1965, is believed to be the locomotive now at Steamtown. Rated at 800 horsepower at 800 revolutions per minute, this was a standard "BB" or two four-wheeled-truck switching locomotive.

On October 15, 1964, the Wabash Railroad merged with the New York, Chicago & St. Louis Railroad (the "Nickel Plate Road") and the Norfolk and Western Railway under the name of the latter. In the reorganized motive power roster of the Norfolk and Western, No. 132 is believed to have become No. 3132.

Like the Wabash, the Nickel Plate Road had a long history in the 19th century, and also like the Wabash, had been in and out of reorganizations symbolized, as often was the case, by the change in the last word of the railway's name from "railroad' to "railway" and vice versa through the years. The New York, Chicago & St. Louis Railway of the 19th century went into bankruptcy in the depression of the 1880s, and on May 19, 1887 was sold to investors who on September 17, 1887, incorporated the New York, Chicago & St. Louis Railroad in New York, Pennsylvania, Ohio, and Indiana. The New York Central owned a controlling block of stock for many years, until on July 6, 1916, the New York Central sold the Nickel Plate to interests represented by the brothers O. P. and M. J. Van Sweringen. The Van Sweringens reorganized the company as the New York, Chicago & St. Louis Railway, resurrecting the pre-1887 name, in April 1923 in order to swallow a number of subsidiary railroads. The Nickel Plate Road operated trains from Buffalo, New York, to St. Louis, Missouri, touching at Wheeling, West Virginia; Chicago and Peoria, Illinois; Indianapolis, Fort Wayne, and Muncie, Indiana; and Canton, Cleveland, Toledo, and Zanesville, Ohio.

Under an Interstate Commerce Commission plan for nationwide railroad consolidation, the Chesapeake & Ohio Railroad obtained control of the New York, Chicago & St. Louis, but disposed of that control in 1947. For a while, in connection with the Erie-Lackawanna, the Nickel Plate offered the shortest rail route from Buffalo to St. Louis.

Similarly, the Norfolk and Western Railway had played corporate musical chairs with its name, though not as many times as the Nickel Plate. The old railroad had gone under during the depression of the Gay Nineties, a Norfolk and Western Railway having emerged on September 24, 1896. It operated 2,747.56 miles of track from Norfolk, Virginia, west through the soft coal fields of West Virginia on to Columbus, Ohio, with branches to Hagerstown, Maryland; Norton, Virginia; Winston-Salem and Durham, North Carolina; Bristol, Tennessee; and Cincinnati, Ohio. During the late 1950s, the N&W dieselized faster than any other Class 1 railroad in the United States, and in a mere five years dropped the fires forever on one of the most modern fleets of steam locomotives in the United States.

The Interstate Commerce Commission consolidation plan assigned the Norfolk and Western Railway to the Pennsylvania Railroad group, under whose control the N&W fell for a number of years. On May 14, 1959, the N&W merged the proud old Virginian Railway into its system, and another famed railway name vanished from the pages of the Official Guide.

By the end of 1961, the company had 576 diesel-electric locomotives (and 19 electric from the old Virginian). On March 17 of that year, the Norfolk and Western Railway filed an application with the Interstate Commerce Commission, asking sanction for a merger of the N&W and the Nickel Plate Road. What emerged on October 16, 1964, was the merger of the Norfolk & Western not only with the New York, Chicago & St. Louis, but also with the Wabash and the Pittsburgh and West Virginia, the enlarged company to operate under the Norfolk and Western Railway name. Thus, more names of major railroads faded from the pages of American industrial history.

The history of the little SW-8 switching locomotive built in February 1953 has not been researched, but its character limited it pretty much to the role of yard switcher. In 1983, the N&W renumbered it 3732 to avoid numbers conflicting with those of an SD-45. Whether the merged company used it much, or moved it to serve elsewhere than St. Louis, if in fact that was its home station, is unknown. Nor does the record indicate its later disposition until in 1987 it came to Steamtown, where the Steamtown Foundation repainted it in Lackawanna colors and gave it the number 500, a fictional number and color scheme for a locomotive that had no historic connection with the Delaware, Lackawanna & Western Railroad.

Condition: This locomotive is repairable for use in switching.Recommendation: When required, this diesel-electric switcher will prove useful around the Scranton railroad yard, for a diesel can be started much more easily than a cold steam switcher can be steamed up. It should be repainted in its original Wabash color and lettering scheme.

A Wabash Railroad locomotive diagram

provided the statistics on Class D8 EMD SW-8 diesels in 1963.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Dover, Don. "All About SW's." Extra 2200 South: The Locomotive Newsmagazine, Vol. 9, No. 12, (July-Aug. 1973): 20-25.

_______, and George Berghoff. "Wabash Railroad: All Time Diesel Roster." Extra 2200 South: The Locomotive Newsmagazine, Vol. 14, No. 1 (April-May-June 1990): 17-29.

Dressler, Thomas D. "Norfolk & Western Diesels." Railroad Model Craftsman, Part 1, Vol. 38, No. 11 (Apr. 1970): 19-24; Part II, Vol. 38, No. 12 (May 1970): 21-24.

Heimburger, Donald J. Wabash. River Forest: Heimburger House Publishing Company, 1984: 119, 120, 260.

Moody's Transportation Manual, 1962. New York: Moody's Investors' Services, Inc., 1962: 65-68, 841-856, 1135-1147.

Poor's Manual of Railroads, 1920. New York: Poor's Publishing Company, 1920: 908-910, 1427-1432.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

stea/shs/chap5.htm

Last Updated: 14-Feb-2002