|

Statue of Liberty

Celebrating the Immigrant An Administrative History of the Statue of Liberty National Monument, 1952 - 1982 |

|

CHAPTER 6:

THE YEARS OF NEGLECT AND DETERIORATION, 1965-1976

Soon after President Johnson issued his proclamation making Ellis a part of the Statue of Liberty National Monument, Secretary of the Interior Udall commissioned noted architect Philip Johnson to create a plan for the development of the former immigration station. Philip Johnson, generally regarded as one of the more innovative men in his field, had earlier designed the New York State Theater at Lincoln Center. In July 1965, the architect met with NYC Group Superintendent Townsley, Regional Director Lee, and Donald Benson of the EODC on Ellis to inspect the area. By then many of the buildings were showing clear signs of neglect and decay because the GSA, considering the island no longer its responsibility, had shut off heat and other utilities. The NPS kept only a single guard on the premises by day and a watchdog at night. This was insufficient to prevent intruders, coming by boat usually from the nearby Jersey shore, from landing and stealing fixtures, hardware, and any other movable property of value. These conditions may have influenced the plan that Philip Johnson devised for Ellis.

The architect proposed that the principal structures of the former immigration depot, including the main building, the hospital buildings, the ferry slip, and the old Ellis Island ferry, not be restored to their original state, but be stabilized as historic ruins. Wood and glass would be removed, roof and masonry retained. Around the buildings the NPS would plant vines, poplars, sycamores, and ailanthus, allowing these to grow unchecked up and through the structures. A moat dug around the historic group would isolate it from the rest of the island. "The effect would be a romantic and nostalgic grouping through which the visitor would pass along raised concrete walkways." All other buildings would be demolished.

Philip Johnson further suggested that the circular shape of Fort Clinton at the Battery and Fort Williams on Governors Island should be continued, with the construction on Ellis of a 130-foot high "truncated cone," to be called the "Wall of Sixteen Million." Visitors could walk upon great ramps which would wind around the inner and outer faces of the cone. There, they would view photographic reproductions of old ships' manifests, listing the names of the sixteen million immigrants who had passed through the place. The Johnson Plan, in addition, called for creating an off-shore restaurant, a picnic grove, a viewing pyramid for looking at the skyline of lower Manhattan, and a ceremonial field for band concerts, observances of ethnic holidays, and other festivals.

At a press conference at Federal Hall on February 24, 1966, the architect officially presented his scheme for development of Ellis Island to Secretary Udall. The latter stated that he endorsed the proposals, as did New York Senator Jacob Javits, who also attended the affair. [1]

The press generally reacted to the Johnson plan quite differently from Udall and Javits. A columnist in the Herald Tribune wrote, "I think I have never read of a project more outrageous." The proposed wall of names was "ugly," resembling a "monstrous gas tank." Besides, she wrote, what could be more absurd than "phoneying up with vines a group of commonplace late nineteenth century and early twentieth century utilitarian buildings?" A World Telegram and Sun article, entitled "The Cult of Instant Ugliness," declared that making ruins out of the buildings on Ellis was "romanticism run riot." A New York Times editorial argued, "Of all the symbols to use in the projected national shrine at Ellis Island, a wall would seem to be the least appropriate. Walls are built to exclude....Ellis was America's gateway for six decades. . . ." Ada Louise Huxtable, architecture critic for the Times, was one of the few with a good word for the Johnson plan. "It is light years ahead," she wrote, "of the routine reconstructions and predictably pedestrian memorials usually tendered by government agencies."

Whether it liked this 1966 proposal or not, the NPS soon realized there was no way it could implement the Johnson scheme, because to do so would require far more money than the $6,000,000 that Congress had authorized for the development of Ellis. Indeed, as the Vietnam War consumed an ever larger share of tax revenues, Congress failed to appropriate even the $6,000,000 it had authorized. The Johnson plan, therefore, was placed on the shelf. [2]

On a much more modest scale, the NPS proceeded to arrange for the establishment of a Job Corps Conservation Center and recruit the workers for the island that President Johnson had promised at the time he incorporated Ellis in the Statue of Liberty National Monument. On December 15, 1965, Superintendent Townsley travelled to Trenton to meet with the New Jersey Governor's staff and finalize the leasing of land on the Jersey shore by the NPS for constructing the camp. Northeast Regional Director Lemuel Garrison presided over groundbreaking ceremonies at the site in February of 1966. By the following January, the Liberty Park Job Corps Conservation Center (as it was named), administered jointly by the Office of Economic Opportunity and the NPS, was completed. It consisted of ten buildings with accommodations for some 200 teen-aged corpsmen. During 1967 these young people cleared land for development of Liberty State Park in New Jersey and worked on cleanup and repairs at Ellis. Before they could accomplish much, however, the OEO announced that due to lack of funds it would have to close sixteen Job Corps Centers by June 30, 1968. The Jersey camp was one of them. [3]

During this same period, the Department of the Interior received an offer of help in developing Ellis Island which must have seemed quite welcome in light of the failure of Congress to appropriate funds. The offer came in a letter to Secretary Udall from Maxwell M. Rabb, president of the United States Committee for Refugees, a private group organized in 1958 and interested in refugee resettlement and immigration. Mr. Rabb, a New York attorney, indicated that he and several other members of the committee, including Edward Corsi and Dr. R. Norris Wilson, had already met with Northeast Regional Director Lee to explore ways that they might cooperate with the NPS. [4]

Udall gave his blessings to the collaboration, and on August 3, 1965, Lee discussed with Wilson, Corsi, Rabb, and others the possibility of organizing a National Ellis Island Association, Inc., to raise money for development and assist in making plans for interpretation of the site. The counsel for the U.S. Committee for Refugees even drafted a certificate of incorporation for this proposed body. After further talks and incorporation in New York State as a non-profit fund-raising group, the National Ellis Island Association, Inc., signed a cooperative agreement with the Secretary of the Interior and the NPS on July 12, 1966. According to the terms of that document, the NEIA, Inc., would the National Park Service, when requested, in its programs of interpretation on Ellis Island. . ., organize and sponsor appropriate special events" on the island in conjunction with the NPS, and "receive funds contributed to it by the American public" for development of the former immigration station, and turn these monies over to the NPS. Unfortunately for all concerned, the NEIA, Inc., never got its fund-raising campaign started, and the whole organization proved short-lived, with no signs of activity after 1967. [5]

As a result of Congress' failure to appropriate money, the removal of the Job Corpsmen, and the stillborn efforts of the NEIA, Inc., conditions on Ellis grew steadily worse. Between 1965 and 1973, officials at the STLI NM received only $676,000 to maintain the former immigration depot, a pitifully inadequate sum. The NPS, therefore, could not afford to heat the buildings, pipe water to the island, or provide other utilities. Without heat in winter, the buildings quickly deteriorated. To make matters worse, the roofs leaked, whole chunks of plaster fell from the ceilings, and the seawall surrounding the island was cracking. Weeds and other vegetation grew wild and unchecked. Intruders continued to trespass on the premises, committing acts of vandalism and theft. They stole copper, brass, and other metal fittings and, in one instance, a whole section of copper sheeting from the roof of a building. [6]

A New York Times reporter who visited Ellis early in 1968 described what he beheld:

. . .the island ferryboat that once took about one of every ten immigrants to Manhattan is a crumbling shell. It floats next to a concrete dock that is collapsing in places.

Green copper sheeting has blown off one of the four cupolas that make Ellis's red-brick main registration building a harbor landmark. Inside, old bedframes and mattresses are stacked in disuse. Tables, benches, and chairs lie about haphazardly. The floors of side rooms are strewn with broken ceiling plaster. . . .

|

|

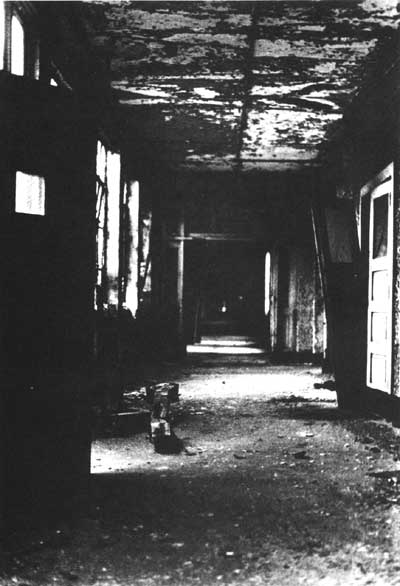

Corridor in the hospital buildings on

Ellis Island, showing the deteriorated condition of the former

immigration station, July 18, 1973. (Source: Photograph Collection of the American Museum of Immigration, Liberty Island, U.S. Department of the Interior, NPS) |

In the 1930s, Edward Laning and other artists in the employ of the Works Progress Administration had painted murals in the dining hall, library, and recreation room of the main building. These works of art had suffered greviously. In 1963, Superintendent Foster had arranged with the GSA to remove two sections (each seven by seven feet) of the oil murals from the library and recreation room to Liberty Island for possible use eventually in the planned museum of immigration. As late as 1967, they were still stored in the utility building there, each rolled on a cylinder and hung from rafters by ropes. When Museum Specialist Walter Nitkiewicz inspected them in December of that year, he found the ropes encircling the suspended drums had dug deeply into the canvas, causing serious damage to the paintings. The Laning oils left behind in the dining room had fared even worse. Nitkiewicz reported:

Four years ago roof leaks were permitting water to flow over the right side of the mural. Large losses of paint had already resulted. Since then leaking and consequent water damage have continued. A large segment of the canvas hangs loose from the wall. I judge this extremely damaged section of the mural to be beyond restoration. [7]

While the island and its facilities rapidly deteriorated, interest in it continued at a high level. Articles in the press, such as the New York Times's "Ellis Island at Low Point in Its History," attempted to tell the public about the sorry state of the historic site. In July 1965, a WCBS-TV crew visited Ellis to shoot a documentary about the former immigration station. It was shown in the fall on a program called "Eye on New York." WNBC-TV sent a crew of twelve to take footage on the premises for a feature on immigration, entitled "An Island Called Ellis." It was first shown on WNBC-TV on January 13, 1967, and is at the present time regularly played for visitors to the Statue of Liberty as a part of the NPS' program of interpretation.

The NPS was also still interested in properly developing Ellis and opening it for the public if funds for the purpose ever became available. For this reason, in February 1968, the Service appointed a team consisting of architects, landscape designers, museum specialists and historians, headed by David Kimball, to draw up a master plan for its neglected property.

By June 1968, the team had completed its assigned task. Their "Master Plan for Ellis Island" ignored the Philip Johnson proposals, harking back instead to some of the ideas expressed in the 1964 study report prepared for the Muskie Senate subcommittee. The master plan called for retention of the main immigration building "as a memorial to the immigrant and as the key to effective interpretation" (Fig. 5). That structure was to be handled in the following manner:

Its central block will serve as an exhibit in place, with restoration of its three front central doorways and the original stairway from the first floor to the second floor examination room. Its west wing will be rehabilitated and adapted for interpretative (ground floor) and office (second floor) use. Remaining spaces will be stabilized and given the minimum heat and maintenance required to prevent deterioration.

The plan stated that all other structures, except for the ferry boat "Ellis Island," existing covered walkways, and three buildings constructed in the 1930s, should be removed. The ferry house, immigrant building to the rear of it, and the recreation hall at the head of the fill between islands two and three (all put up in the 1930s and still in relatively good condition) should be retained because they offered large covered spaces that would prove useful during the period of development work on Ellis. Afterwards, they too should be demolished. [8]

The master plan went on to divide the site into three physical segments: the north unit, containing the main immigration building, would communicate the park story; the south unit, cleared of its original buildings, would serve as an activity area and a center for ethnic observances; the fill joining these two parts would act as a transition between them. On the south unit, the plan provided for facilities necessary to support ethnic events and a concession food service. Space might also be reserved for a restaurant and for seating at recreational programs if either of those proved desirable in the future.

Access to Ellis would be by boat from Liberty Island, until Liberty State Park in Jersey City was finished. Then, shuttles could operate from there as well.

Since all of this repair and demolition would take time, even after or if the money to implement the plan became available, the team recommended interim use of Ellis. A limited number of visitors should be permitted to take guided tours. They would be brought by boat from Liberty Island, landed at the ferry slip in front of the main building, conducted into it through the southwest tower and up to the examination room on the second floor. There they would hear a talk on "the historic use of the room and its significance, and view photo murals of the room" as it appeared early in the century. To do these things, however, the NPS would first have to rehabilitate the ferry slip seawall, commission a thorough inspection of the main building to make sure it was structurally safe for the public to enter, clean up and repair the portions of the main building to be included in the tours, negotiate a concession contract for boat service, and provide temporary restrooms.

Team members disagreed among themselves about the recommendation to demolish so many of the existing structures on the island. A minority of the group, and many of the NPS officials who afterwards reviewed the master plan, felt strongly that the hospital buildings along the ferry slip and the kitchen-restaurant structure adjacent to the main building should be kept, to preserve the "architectural composition as a whole" and allow the visitor to see "substantially the same picture the immigrants saw when they arrived at the island." [9]

With this question still not fully settled, the director of the NPS approved the master plan in November 1968 and asked the Eastern Service Center to estimate the cost of its implementation. In April 1970 the center provided the requested information. [10] Its report stated that to accomplish the minimum construction necessary for producing a "permanent type workable facility" required $3,950,600. With this amount, the NPS, during phase I of the work, could repair the seawall; dredge the ferry basin and channel and remove the wreck of the "Ellis Island" (which in 1968, after the master plan was written, had sunk during a storm); install water and sewage systems and electrical service; and initiate architectural, plumbing, heating, and air-conditioning work in the main building and landscape the grounds immediately around it. During a second phase, the demolition on islands two and three could commence; covered walks would be modified and new connecting ones built; islands two and three would be landscaped; and dock shelters erected. These phase II activities would cost approximately $609,400. In the third phase, the NPS would repair the balance of the seawall, requiring $284,700.

The estimators pointed out that interpretative facilities would also be needed for the site, which they thought might be provided for $50,000. They noted too that $184,000 had already been spent for reroofing the main building and other miscellaneous items. [11]

Judging from cost studies made only a few years later, one must conclude that the figures presented in this report were unrealistically low. Perhaps the reason for this underestimating was the concern of the Eastern Service Center team with staying within the $6,000,000 limit earlier imposed by Congress. In addition, the figures covered construction work only, ignoring the costs of planning, supervision, operation and maintenance, and personnel services.

Congress did not appropriate even this minimal amount. Thus, the master plan which had received official approval, like the Johnson one which was never formally accepted, lay on the shelf gathering dust. The NPS even lacked the money to follow the interim proposal of opening the facility to limited visitation. At this point, however, some parts of the public attempted to impose their own ideas concerning utilization of Ellis Island.

At 5:30 a.m., on March 16, 1970, an eighteen-foot boat pushed off from the New Jersey shore heading for the former immigration station. It carried eight Native-Americans and assorted supplies for setting up camp on the island. A faulty gas line, however, aborted the plan and left the intruders adrift until the Coast Guard rescued them. When they vowed to attempt another landing, the Coast Guard stationed two patrol boats near Ellis, proclaimed a "zone of security" around it, and pointed out that under the provisions of the Espionage Act of 1917, unauthorized squatters could receive jail terms of up to ten years.

Shoshone Indian John White Fox, who had participated in the occupation of Alcatraz in San Francisco Bay the previous November, read a statement to the press explaining what the Native-Americans wanted to do with Ellis. "There is no place for Indians to assemble and carry on tribal life in this white man's city." The island, he proclaimed, should become a living center of Indian culture and house a museum with exhibits illustrating what whites have contributed to red men: "disease, alcohol, poverty and cultural desecration." [12]

Four months later, a second, more successful occupation of Ellis occurred, this time by 63 black men, women, and children belonging to a group called the National Economic Growth and Reconstruction Organization (NEGRO). Dr. Thomas W. Matthew, a 46-year-old, black neurosurgeon, had founded NEGRO in 1965. He was philosophically against welfare and proposed instead to rehabilitate drug addicts, alcoholics, ex-convicts, and the chronically dependent by offering them job-training and employment in labor-intensive black-owned businesses.

For thirteen days (July 20 to August 1) the little band of illegal squatters held Ellis, while Matthew announced he intended to lease and perhaps eventually purchase the island from the NPS in order to develop it as a rehabilitation center for 2,500 drug addicts, alcoholics, ex-convicts and their families. He planned to set up light manufacturing projects (such as producing shoes, packaging chemicals, and assembling electronic equipment.) that would train and employ these people. In addition, his self-help community would refurbish the great hall as a monument to immigrants: NEGRO would use it to hold ethnic festivals and celebrate special holidays, inviting the appropriate immigrant group to attend. The Irish, for example, would be welcomed on St. Patrick's Day to participate in dancing Irish jigs and singing Irish songs. To finance these undertakings, Matthew intended to sell $6 million worth of interest-bearing bonds to foundations, businessmen, civic leaders, and other interested parties.

During the thirteen-day occupation, Matthew and representatives of the NPS worked out an agreement. His followers ended their illegal stay on the property, and the NPS granted a special use permit to NEGRO, commencing September 1, 1970, and good for five years. [13] That document allowed the organization to occupy the buildings and grounds on the south portion of Ellis for residence and light industrial projects. They were not, however, to use or in any way alter the great hall or other rooms on the north side of the island, without approval in advance from the superintendent of the STLI NM. NPS officials, further, retained the right to visit and inspect the area to check compliance with local and federal laws concerning public health and sanitation and with the terms of the permit. [14]

In the months that followed, Dr. Matthew apparently had little success in raising the amount of capital needed to finance his schemes, nor did he attract many settlers. Only four NEGRO members lived full-time on Ellis during the winter of 1970-71. Twice, the superintendent from Liberty Island accompanied sanitary engineers from the United States Public Health Service on inspection tours of the site. STLI NM Superintendent Arthur Sullivan and a public health engineer dropped in on September 14, 1970, only to be ordered off the premises by NEGRO members, who said the officials could not visit unless accompanied by Matthew. The officials returned with the doctor on September 21 and succeeded in making their inspection. The public health engineer's subsequent report stated that there were numerous safety and health hazards, such as collapsed sections of the seawall which undermined portions of sidewalks, questionable structural stability of the hospital buildings, and lack of a potable water supply, adequate plumbing, or heating. These conditions could lead to an outbreak of communicable diseases, or a major fire might start as inhabitants attempted to keep warm by burning the wood and debris scattered about the site. In addition, NEGRO members had ignored the prohibition on use of the buildings on the north side of the property. The report, therefore, recommended that NEGRO find a different location for its projects and "return Ellis Island to the original NPS plan for historical renovation."

Six months later, a second inspection group that included NYC Group Superintendent Wagers and STLI NM Assistant Superintendent Batman found essentially the same conditions. Although Dr. Matthew's followers had engaged in clean-up work on the grounds and interiors of the buildings, the hazards, in fact, had grown worse. The safety engineer's report stated:

On Ellis Island, NPS is allowing continuation of a permit for limited use of a deteriorated, delapidated, unsanitary facility which is likely to result in disease, injury or death to one or more of the permittees.

The only sensible recommendation from the health and safety point of view is the immediate revocation of the permit to NEGRO.

Though the NPS did not act on this recommendation for two years, NEGRO itself abandoned its project. During the summer months, the number of NEGRO-affiliated workers on the island rarely exceeded five; in September 1971, the last three residents left. Jerry Wagers officially ended the Matthew episode when, in April 1973, he sent the doctor a registered letter announcing termination of the permit. [15]

Ellis once again lay deserted and neglected, when it attracted the attention of President Nixon. On his way to the dedication of the American Museum of Immigration on Liberty Island, in September 1972, the President noticed the neighboring site, with its imposing main building, and expressed interest in rehabilitating the landmark in time for the nation's bicentennial celebration in July 1976.

The President's newly aroused enthusiasm led the Department of the Interior to explore further options for handling Ellis and their potential costs. The under secretary requested that the Northeast Regional Office of the NPS conduct a study of the possible alternatives and submit its findings. Regional Director Chester Brooks fulfilled that assignment in April 1973, when he forwarded to the head of the NPS an option paper prepared under the supervision of Jerry Wagers, New York District chief.

This document pointed out that Congress had thus far appropriated only $752,130 of the $6,000,000 authorized for development of the island. That money had been spent to reroof the main building and make a few emergency repairs. Such minimal work, however, had done little to arrest the progressive deterioration of the property. Indeed, advancing dilapidation, vandalism, and theft, coupled with inflation, had made the 1968-70 cost estimates "grossly inadequate."

The study went on to summarize five options. 1) Rehabilitate the entire main building and hospital, rebuild the ferry dock and seawall, dredge the ferry basin, provide utilities, demolish all other structures, landscape north and south sides of the island, and provide concessioner, interpretive, and protective facilities, including seven residences. Development cost--$46,751,000. 2) Rehabilitate a little over half of the main building, while stabilizing the rest for structural safety. Only the rehabilitated portion would be open to the public. Demolish all other structures on the north side of the island. Rebuild the ferry dock and north side of the seawall and dredge the ferry basin. Leave the south side of the island as it was and closed to the public. Development cost--$20,935,000. 3) The federal government would attempt to interest private groups and businesses in developing a convention center, a hotel, or housing projects on parts of Ellis. The NPS would rehabilitate only the main building as a museum. Development cost (private)--$50,000,000, (federal)--$21,000,000. 4) Similar to option three, except that the NPS would retain only a portion of the main building for visitor services and interpretation. Development cost (private)--$60,000,000, (federal)--$16,000,000. 5) "Turn the island back to GSA for disposal as surplus property."

Options one through four were well above the $6,000,000 limit imposed by Congress and would, therefore, require authorization of additional funds. The fifth alternative would need legislation disestablishing the former immigration station as a national monument. [16]

The Northeast Regional Office recommended that option two be followed because "it would provide the essential visitor experience in the main building while retaining all other options for future consideration." Ronald H. Walker, NPS director, and Nathaniel P. Reed, assistant secretary for Fish, Wildlife and Parks, concurred, but apparently Rogers C. B. Morton, secretary of the interior, did not. At a meeting on May 15, 1973, at the Theodore Roosevelt Birthplace House, Morton remarked that he did not want any part of Ellis Island. It would be too expensive to rehabilitate. He intended, therefore, to speak to the President about returning it to the GSA for disposal.

Secretary Morton's statement shocked many of the members of the Interior Department and the NPS, including Superintendent Batman and the curator of the AMI, both of whom wrote memoranda arguing against such a course. As Museum Curator Kallop put it, "disposal of Ellis Island by the Park Service " would be seen by the "vast public of Americans newly conscious of their ethnic heritage as a denial by the government of a commitment made to the public to rescue and rehabilitate the Island." It would be denounced by the press and by critics of the AMI, who see the development of Ellis as "an opportunity to rectify what they consider the mistakes of the Museum." In short, getting rid of the historic site could be "truly explosive." [17]

It was this "truly explosive" potential, perhaps, that prevented Secretary Morton from having his way on the disposition of Ellis. Congress, on the other hand, showed no inclination to approve or appropriate the sums required for the other four alternatives. In the face of this situation, NPS Director Walker wrote a memorandum in June 1974, outlining the possibilities of raising funds for rehabilitation work on the island from labor unions, ethnic groups, and other private-sector sources. To further Walker's proposals, Under Secretary of the Interior John C. Walker gave his approval to a plan to bring a group of ethnic leaders to Ellis and explore with them the formation of an organization to raise money for development of the historic site.

Before this visit occurred, in November 1974, however, one concerned private citizen was already taking action. Dr. Peter Sammartino, founder and president of Fairleigh Dickinson University in New Jersey, was the child of Italian immigrants who had once passed through Ellis. While taking a helicopter trip over New York harbor in January 1974, Sammartino hit upon the idea of launching an effort to restore the area. He presented his thoughts to the International Committee of the New Jersey Bicentennial Celebration Commission, which he chaired. In July, the committee unanimously voted "to further the establishment of a museum and recreational park on Ellis Island."

That summer, Sammartino made an inspection of the island in the company of Ed Kallop and mentioned to the AMI curator that as a first step he and the other Bicentennial Commission members would try to "pry loose" the $6,000,000 earlier authorized by Congress. Sammartino believed that he and his colleagues, acting as a pressure group, might have better success in achieving this than the Park Service people. He proceeded to write to President Nixon, Secretary Morton, Senator Harrison Williams, Jr. (Democrat-New Jersey), and other senators. He also publicized his ideas through letters to the press, including the one that appeared in the Newark Star-Ledger in October 1974.

In all of these communications, Sammartino argued that Ellis Island had to be restored. To allow it to deteriorate further was a national disgrace. A complete job of rehabilitation would cost $20,000,000 or more, an unthinkable sum to expend in a time of "inflationary crisis." The work, therefore, should be done "piecemeal." Through joint Congressional action and voluntary help, enough money could be raised to restore the large reception hall in the main immigration building and the passages leading to it, and open these to the public in time for the bicentennial. [18]

In November 1974, the NPS held its planned tour of Ellis for a group of ethnic leaders, and naturally invited Sammartino to participate. Others who came included Rudolph Vecoli of the University of Minnesota's Center for Immigration Studies (who had been severely critical of the AMI); Edward J. Piazek, Polish community leader; Myron B. Kuropas, Ukrainian Congress; and Michael Sotirhos, United Greek Charities. The guests were appalled at the deteriorated state of the facility and said Congress must demonstrate its interest and concern by appropriating funds to correct the situation. The group decided further that, while pressing the legislators to provide money to open the island to limited visitation, it should seek supplementary help from the private sector. To further these ends the group designated Sammartino temporary chairman of an ad hoc committee to restore Ellis Island.

Sammartino came away from that gathering more determined than ever to achieve their goals quickly. In April 1975 the Restore Ellis Island Committee incorporated as a non-profit organization in the State of New Jersey, with Sammartino as its national chairman. The committee requested that Congress add to the fiscal 1976 budget a supplemental appropriation of $1.5 million to be used for restoring the landing pier, the walk and the stairway to the reception hall, plastering and painting the hall itself, and providing water and outdoor toilets, so that this limited portion of the main immigration building on Ellis Island might be opened to the public by the bicentennial year. To reassure law makers that they would not be taking on huge expenditures in the future for upkeep and further wide-ranging development, the committee suggested that 90 percent of the structures on the island should be torn down, leaving just enough brickwork to give an idea of the former buildings and to form picnic alcoves for visitors.

In the spring of 1975, Sammartino and his wife travelled to Washington to lobby for their proposals. Congressman Edward Patten of New Jersey agreed to draft the required bill. The Sammartinos managed to line up the entire New Jersey congressional delegation and part of New York's behind the legislation. They went to see Congressman Sidney Yates (Democrat-Illinois), chairman of the House Appropriations Committee, and persuaded him and several other members of that key committee to visit Ellis in May 1975 to see for themselves the crying need for repairs. Sammartino wrote to President Gerald Ford, asking for his support as well. [19]

Meanwhile, NPS officials and the Restore Ellis Island Committee did what they could to obtain media backing for the appropriations bill. Luis Garcia-Curbelo, unit manager of the STLI NM, told reporters he had so far received virtually no money to maintain the immigrant memorial. "I feel like crying" he said. "It's shameful. Ellis Island represents so much to America. We have to take action to preserve it." Alistair Cooke included Ellis Island in his "America" series on public television and Dan Rather of CBS did a short piece about the site for network news. Locally, WCBS-TV endorsed the restoration in a broadcast editorial.

In April 1975, Sammartino drafted a letter to the Secretary of Labor, which was sent over the signature of Garcia-Curbelo, requesting laborers under the Comprehensive Employment and Training Act (CETA). In September the CETA crew set to work, cleaning the first floor and the great hall on the second floor of the main immigration building, gathering together some of the building's original benches, and clearing the ground around the structure. On November 5, 1975, the NPS held a flag-raising ceremony on the island to honor the Restore Ellis Island Committee and the CETA workers. Sammartino and Jerry Wagers, now director of the North Atlantic Region, spoke of their hopes for the national monument before some 125 guests and members of the press.

All of these efforts paid off when Congress passed the appropriations bill and President Ford signed it into law on January 1, 1976. It provided $1,000,000 for limited rehabilitation and authorized the NPS to use $500,000 of its budget annually for operating expenses. With some money finally assured, the NPS put into action its plans for opening Ellis to the public by the spring. [20]

Responsibility for readying Ellis went to the North Atlantic Regional Office, headed by Jerry Wagers. On January 6 and 7, meetings took place to outline what had to be done. There were follow-up gatherings in Boston in February and New York in April. The participants, including Denis Galvin, associate regional director, Park Service Management; Dick Volpe, regional chief of maintenance; William Hendrickson, superintendent, NYC Group; Ross Holland, associate regional director, Planning and Resource Preservation; STLI NM Unit Manager Luis Garcia-Curbelo; and others, decided that the $1,000,000 appropriation would be used "primarily to establish visitor use on the island and secondarily to preserve the resource there."

They commissioned URS/Madigan-Praeger, Inc., of New York to survey the structural soundness of the main building and assess potential safety hazards to visitors along a proposed tour route. The company found water intrusion had dangerously loosened plaster on walls and ceilings. Structural steel, where visible, was badly rusted, and ice had penetrated masonry, causing ever-widening cracks. These hazards would have to be corrected along the tour route. The survey made it very clear that visitors must not be allowed to stray into other areas. [21]

Laborers were hired to try to make the main immigration building waterproof by repairing the roof, replacing broken windows, opening surface drains, fixing downspouts, and rehabilitating skylights. Work crews also removed loose plaster, cleared away piles of debris in the passageways leading to the historically important areas in the main building, and chopped down overgrown vegetation surrounding it. Contracts were let out for supplying the island with water, sewer, and toilet facilities, as well as a lighting system. A radio hook-up between Liberty Island and Ellis was installed. To safeguard these improvements the NPS, in May 1976, instituted 24-hour security protection for the former immigration station, bringing to an end the theft and vandalism of the past.

Since complete repair of the seawall was estimated at a cost of more than $4,000,000, the team responsible for readying Ellis decided to limit repairs to the section around the ferry basin. This consisted mainly of putting stones back in place and repointing them.

The Army Corps of Engineers undertook the dredging of the ferry basin. When it became obvious that this operation could not be completed prior to May 1976, the target date for opening, the NPS also arranged for a temporary dock to be installed on the north end of the island, where the water was sufficiently deep to land a 100-passenger boat. William Henrickson asked Francis Barry, president of the Circle Line-Statue of Liberty Ferry, Inc., to obtain a vessel suitable for transporting 100 to 125 visitors at a time from Liberty to Ellis Island. By March, the company had located and chartered such a boat.

Meanwhile, the regional office assigned a task force to develop an interpretive plan. By February, Ed Kallop, now regional curator and a member of that task force, had done so. The guiding principle behind his interim interpretation plan was to help visitors experience how it might have felt to be an immigrant arriving at Ellis in the first two decades of this century. With some modifications suggested by Paul Weinbaum, who succeeded Kallop as AMI curator, the interpretive plan became the one followed by tour guides, starting in May 1976. Those tours were designed to take one hour. Owing to the deteriorated condition of the facility, the tour could show the public only limited parts of the main immigration building, including the great registry room.

With all work proceeding as scheduled, Jerry Wagers could inform an anxious Congressman Yates that Ellis would indeed be ready for regular visitor use by late May. Wagers could also arrange with Dr. Sammartino for the development of appropriately festive opening ceremonies. [22]

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

stli/adhi/chap6.htm

Last Updated: 24-Sep-2001